Trinculo:

Legg'd like a man! and his fins like arms! Warm, o' my troth! I do now let loose my opinion, hold it no longer: this is no fish, but an islander, that hath lately suffer'd by a thunder-bolt. [Thunder.] Alas, the storm is come again! My best way is to creep under his gaberdine; there is no other shelter hereabout: misery acquaints a man with strange bedfellows. I will here shroud till the dregs of the storm be past.

The Tempest Act 2, scene 2, 33–41

Most jazz musicians speak freely about their mystical experiences when playing jazz. Fela Anakulapi Kuti, the man who carried death in his pocket, spoke quite freely to me in 1989 in his Lagos club, the Shrine, about the spirituality of Black music. He said that playing music was his sacred calling, his destiny. Others have used similar language in relating their musical experiences of the mystical. Often the phrase heard was that the instrument played them; they did not play it. They became a conduit of the sacred. Although I knew from a young age that I wanted to play great music that would let me experience that level of spirituality, I never really could. However, there were two or three times when I tasted a bit of that joy.

One was at a junior high school impromptu dance. For some reason, the administration decided to have a general afternoon off and asked me to gather a group of musicians, letting me ride my bike home to get my tenor sax. I sped home to scoop up my horn. My usual mediocre playing somehow was transformed into something else as I poured out chorus after chorus of music played well above my usual effort. People cheered, one never forgets that sound or the feeling it delivers, and they continued to tell me how good I was. There was nothing else like it. Alas, I fell to my usual level of mediocrity soon enough.

The second time this unusual experience happened was many years later when I was playing at a club in Westchester County, New York. I confess that I was still mediocre and really didn't know what I was doing. But somehow my fingers slid to the high e-flat near the very top of the alto sax’s range. I soared above the combo and held the note for some time. Again getting an ovation and a congratulatory hug from the group’s leader. He asked me where that note came from, shaking his head and smiling. The professional musicians in the group joined the audience in its standing ovation and cheers.

That was just about the sum of my own personal experiences with the transcendent power of music. However, it was enough to give me a glimpse of the addictive power of the eternal now, beyond space and time. It is a feeling where one finds self while being lost to outside forces and people. We can call it a liminal experience with the Turners. Communitas also fits, for while being beyond forces and people outside of one’s self, self is strangely united with them. Whatever term one wishes to apply, one never forgets that blissful merging of self with something beyond self. It was also enough to give me some understanding of what many jazz musicians mean when they state that jazz is spiritual.

The list is a long one but, perhaps, Charlie Parker stated it most clearly when he said that jazz was his religion. John Coltrane echoed that sentiment in using jazz to get in touch with his own spirituality, particularly in the album A Love Supreme. Fittingly there is a church of St. John Coltrane in San Francisco. Of course, it is not only jazz that inspires connections with spirituality.

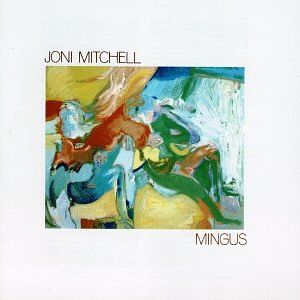

Other forms of music also can lift us to mystical levels. Who, having heard Mozart or Beethoven, for example, has not been transported, even momentarily, to higher realms? Similarly, fans of almost any type of music have at one time or other felt a mystical, spiritual unity with other fans of the music. I dare says most music does not have this effect most of the time. But at any given time this inexplicable emotion can occur. It is the quixotic nature of the phenomenon that may increase its power. Indeed, sometimes seemingly strange combinations of musical styles can become inspirational. In this work, I wish to examine in some detail the seemingly strange pairing of Joni Mitchell and Charles Mingus.

Joni and Charles

To many people from jazz or folk music the pairing of Joni Mitchell and Charles Mingus appeared strange at best. Mingus had a fierce reputation in the jazz world. His race pride bordered on anti-white feeling. Many African-American musicians refused to work with him. Frank Foster, the genial tenor saxophonist, stated to me that he needed his front teeth. Mingus had a reputation of not being above physical fights with his musicians. Others disliked Mingus personally, but worked with him because of the high level of his music. It seemed that Mingus and Mitchell would be an explosion waiting to happen.

Mingus, a major figure in American music, was born in 1922 and died in 1979. He was a composer of great ability as well as a bass player, pianist, and the leader of outstanding small groups. Mingus always noted that his major influences were African-American church music and Duke Ellington, whose music he first heard on the radio at the age of eight. He was able to elicit music from his musicians that was generally far above their usual output, but at great personal anguish to them. To say Mingus was a cruel taskmaster is an understatement.

Mingus studied classical music and bass with H. Rheinshagen, the principal bassist with the New York Philharmonic. He also studied composition with Lloyd Reese. At the same time, he worked with such great jazz musicians as Louis Armstrong, Lionel Hampton, and Kid Ory. Mingus always loved Dixieland or trad music, but moved into modern jazz in the 1950s, playing with his idol, Duke Ellington, as well as the leaders of the modern jazz movement such as Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, and Bud Powell.

Additionally, he began to head his own groups, recording their music on his own labels and publishing it with his own publishing company. To aid young composers, he originated the Jazz Workshop. Not surprisingly, Mingus was a leader of the jazz avant-garde, producing works such as Pithecanthropus Erectus, The Clown, Tijuana Moods, Mingus Dynasty, Mingus Ah Um, The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady, Cumbia and Jazz Fusion, and Let My Children Hear Music. In all, he created more than 100 albums and 300 scores.

Mingus received many honors during his relatively brief life. He taught at universities and saw many of his works used for ballets. Symphony orchestras played his compositions, and his autobiography Beneath the Underdog was published in 1971. Mingus also toured extensively throughout the world. Unfortunately, in 1977, he was diagnosed with Lou Gehrig’s disease, Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Mingus died in 1979, but his music has received many honors and continues to be a major force in jazz and other music.

Perhaps, equally well-known is his ferocious temper. In the jazz community, he had the nickname of The Angry Man of Jazz. He was so committed to eliciting the best from his musicians and his music that he would berate his musicians publicly and privately, often firing them during a performance. He expected their best at each moment, even expecting them to read his mind and anticipate his desires. Additionally, he expected group improvisations analogous to that of early jazz. Interestingly, he often received what he expected. Some of his musicians left and returned to his band over time, like Jimmy Knepper whom Mingus punched in the mouth. This burst of temper led to Mingus’s conviction on an assault charge. Charles McPherson was one of a very few musicians who stayed for a long time with Mingus and managed to stay friendly with him, due, I believe, to his amazing ability on the alto sax and his calm demeanor. In interviews, McPherson gave a balanced view of Mingus as a man and a musical genius: "There was a certain crowd that Mingus attracted amongst the jazz people and they loved him. So he got his just due and he was an interesting figure because he was painfully honest, confrontational, didn’t edit anything - whatever he thought he said - so he wasn’t concerned about being politically correct, which can be quite troublesome. He was always in and out of trouble with people. But that was interesting to watch."

And in response to a question regarding how Mingus treated his band members, McPherson stated in an interview with Shannon J. Effinger: "I used to be very nervous and kind of afraid because he would insult people in the audience who talked during a ballad. He would go out and threaten them and tell them to get out or say, 'Here’s your money…some people are here to listen to the music…you’re not respectful!' He would demand that. Well, some people would have an issue with that, like, 'Who are you to tell me…?' Some people would be intimidated and just be quiet. So working with Mingus was never a dull moment. Interesting musically, but you never knew what was going to happen. And he loved that. I think he welcomed that as being part of his assumed persona in terms of how the world looked at him, how the music world looked at him - a mad genius that’s volatile and might go off at any moment. That worked well because people would come to see him and just wait for something bizarre to happen. And it would. And the next day, somebody would write about it and the next night, you couldn’t get into the place! Some of that he was being himself. He was not unaware that it’s better to get some press than to get no press."

Joni Mitchell seemed to be the exact opposite of Mingus. Where Mingus was confrontational, Joni Mitchell was soft and gentle. Where Mingus was outgoing and filled with a strong belief in his own strength, Mitchell was often unsure and believed others were better than she. Mingus was secure in his music, attached to the past, but sure that he could unpack all that lay in that past to link it to the present and future. Mitchell liked to keep things as they were and when she moved out of her comfort zone she felt very uneasy. According to topsynergy.com, "She is tenaciously loyal, protective, and supportive of those she cares about, and has a very strong nurturing, maternal nature. Joni Mitchell empathizes with others and intuitively senses the feelings and needs of other people. Compassionate and sympathetic, she is easily moved by others' pain, and Joni Mitchell is often the one that others seek out when they need comfort, reassurance, or help."

Unlike Mingus, Mitchell appeared easy to approach. Topsynergy.com reports, "Mitchell's intellect and her emotions are well balanced. Joni has the ability to manage her feelings superbly and have a cautious, adaptable and open way about her. Joni Mitchell likes to associate with the public and has an understanding for the 'man on the street.'" There is little wonder that many speculated how the two would get along and what might come of a collaboration between such opposites.

The Meeting of Charles and Joni

According to Joni Mitchell, she is a longtime jazz fan and jazz was her private music. There is evidence in her body of work that she was inserting more jazz-derived material in her compositions and orchestrations. Certainly, Mingus must have picked up on the influence of jazz in her material. Mitchell notes that it was a few months after the release of Don Juan's Reckless Daughter when she heard rumors that Mingus was trying to reach her and having no luck in so doing. Mingus had heard and been impressed by "Paprika Plains," which Mitchell had orchestrated. Thus he sought a musical collaboration.

Mitchell was a fan of Mingus’s work. She wondered why he wanted to contact her and called him on the phone. His plan was for an album together. Mitchell says that someone played some of her music for Mingus. It was “Paprika Plains.” The piano had been played many times for the recording, and there was a splice between sections recorded at different times. Mingus, known for his keen ear and sense of time, kept telling Mitchell that the song was out of tune. Mitchell notes that when the recording was over Mingus said she had a lot of balls. He meant she had strength in the midst of weakness and he liked it. He liked her adventuresome spirit.

However, being Mingus, one of the more creative people in jazz, it was not a simple album he wanted to do with her. He wanted to do an album based on the work of T. S. Eliot. Mitchell said, "He had an idea to make a piece of music based on T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets. And he wanted to do it with – this is how he described it – a full orchestra playing, one kind of music and overlaid on that would be a bass and guitar playing another kind of music, and over that someone would read excerpts from Eliot in a very formal literary voice, and interspersed with that he wanted me to distill T.S. Eliot down into street language, and sing it mixed in with this reader."

Mitchell was interested, but felt that the concept was too much for her. However, Mingus wanted to work with Mitchell, so he said he had another idea. In April 1978, he called her and said he had six songs for her. Mitchell was to sing these songs and write the words. She went to meet him and found him “devilishly challenging,” but she liked him at once. As aforementioned, Mingus did not have long to live - he had Lou Gehrig’s disease and, in fact, died in 1979 before the record was finished. Thus, the work on the album was rushed. The deadline was, she said, Mingus and whether he would he live till the end of the album.

Mitchell moved to New York City’s Regency Hotel to be near Mingus for the work. The recordings were at Electric Lady Studios in Greenwich Village. From all she has said and written, it is clear that he fascinated her. Like others who got to know him well, she saw the good as well as the controversial sides of his personality. She does admit that when she knew him he was paralyzed and, therefore, not likely to be violent. She noted his poetic character, his openness, and his complications. Interestingly, she saw Mingus as vulnerable. He was quick to cry and quick to become angry. Mitchell said, "He was very true in a certain way and kind of crazy because of it. That’s my take on him, anyway. I may have romanticized it some because I was so fond of him."

Sadly, Mingus did not live to see the conclusion of the project. There had been some joking regarding that fact in the making of the album. These little “raps” were inserted here and there in the work. The final album came out in June 1979. Most people were not sure what to make of it. Jazz fans, by and large, never gave it a chance. I avoided listening to it for years. There were too many other things out there to take up my listening time. I was among the “purists” who basically avoided electric music, smooth jazz, and fusion. Now and then, I might listen to Return to Forever or Weather Report, but always while wondering why such great musicians didn’t stick to straight ahead jazz.

However, my respect for Mingus as a jazz genius kept me musing over the years why Mingus did it. I had no problem with Mitchell’s folk music. I knew she was a solid musician, above the rest of the group. I always loved Bob Dylan’s music, so I did make room for music other than jazz. But the mixing of genres was always difficult for me. Surely, I knew people always stole from “the classics.” If Mozart could collect from all those who plagiarized from him, including Beethoven, his descendants would still be collecting royalties. I often annoy people by pointing out the origin of some of their favorite jazz, rock, and country favorites. However, I was not sure that such borrowing was legitimate.

One can only be so pure up to a point. The temptation to seek out what had been forbidden, even if only by one’s self, is great. Therefore, I began to listen to the Mingus album. Surprises are always good. The bad press was bad reporting. There is a reason its popularity has grown over the years. Even its original “bad” reception was only “bad” in comparison with Joni’s other albums of the time. It just missed the Billboard’s top 100 for 1979. It reached number 17 at its highest point. The videos of her tour to promote the album still draw many “hits” daily. These tapes have many high points. After all, she had the following personnel on the recording and tapes: Joni Mitchell, guitar and vocals; Jaco Pastorius, electric bass and horn arrangement on "The Dry Cleaner from Des Moines"; Wayne Shorter on soprano saxophone; Herbie Hancock on electric piano; Peter Erskine on drums; Don Alias on congas; and Emil Richards on percussion. The videos show how much fun the group and audience had and how well the band cooks. It does not clump along like so many electric efforts – but Jaco and Herbie would never allow that to happen. Pat Methany plays better than on most of his efforts and demonstrates why his fans are so, well, fanatic about his work.

On Joni Mitchell and Relationships

The meeting of Mingus and Mitchell, then, is undoubtedly a meeting of opposites. Other than the old saying that opposites attract, there had to be more happening than simply the attraction of opposites. I believe that Mitchell’s basic personality had much to do with the success of the collaboration. As topsynergy.com has phrased it, "Mitchell has a well-developed personality and tends to base her relationships with others on a more personal level. Joni Mitchell is inclined to seek mental or intellectual relationships and also has a strong desire for soul-unions. Mitchell’s intellect and her emotions are well balanced. Joni has the ability to manage her feelings superbly and have a cautious, adaptable and open way about her."

These characteristics, I think, helped the relationship with Mingus. Certainly, Mingus had a wide appreciation for all types of art and music. Charles McPherson in an email to me noted that Mingus must have heard something in Mitchell’s music that sparked his creativity and imagination. Certainly, by all accounts, they hit it off from the beginning. I don't think it is much of a stretch to believe that her openness to new ideas helped the relationship develop. She was interested in people. Although cautious, she pushed herself into new musical directions throughout her career.

Additionally, she was able to read the emotional climate around her, something very important in getting along with Mingus. Topsynergy.com reports, "Mitchell approaches life emotionally and subjectively and she is sensitive to the emotional atmosphere, the subtle undercurrents of feeling in and around her. Instinctive and non-rational, Joni Mitchell is often unable to give a clear, simple explanation for her actions. Something either feels right, or it does not."

Mitchell said she took a strong liking to Mingus on first meeting him. Indeed, her opening words on the Mingus album notes express her overall feeling and admiration of Mingus: "The first time I saw his face it shone up at me with a joyous mischief. I liked him immediately. I had come to New York to hear six new songs he had written for me. I was honored! I was curious! It was as if I had been standing by a river – one toe in the water – feeling it out – and Charlie came by and pushed me in – 'sink or swim' – him laughing at me dog paddling around in the currents of black classical music."

Although Mingus was by then gone, Joni was still charming him and paying him the proper respect he always seemed to crave. Note also her gratitude that she had been given the final push for her to pursue jazz, Black classical music. She also has stated that she knew many of her fans would not like the album, but she hoped that some of them would follow her into that water.

During preparations for the album, Mitchell made some provisional recordings which show her development along jazz lines. She also broke out of a three month writer’s block with the fine lyrics to “God Must Be a Bogeyman,” which Joni based on the first four pages of Mingus’s autobiography, Beneath the Underdog. Unfortunately, as Mitchell states, by the time she had completed it, Mingus had passed. It has, however, the bite of Mingus’s humor and is in the long jazz tradition of humor.

While Mitchell took the measure of Mingus and certainly read his personality accurately, Mingus also took her measure. Writing six songs for her, knowing that she had been dipping into jazz, stretching out, was a way of gaining her favor as well. Each saw something in the other’s work that could add to their own oeuvre. While retaining their individuality in the collaboration, each also showed something more than had been the case before. I believe Mingus showed where a type of fusion could emerge from their work that led in a different direction than fusion did actually go. Their album revealed the best of jazz and folk and pop through the exploration of their common roots. Mingus’s music evidenced a grasp of jazz history equaled only by Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong. The work of Ernest Aaron Horton puts this fact in perspective: "Considering his musical relationship with Louis Armstrong, Kid Ory, Jelly Roll Morton, and Duke Ellington, a study of Mingus’ history is truly a study of jazz history. However, in order to fully understand the contribution Mingus made it is important to relate his experience of history with his place in the future of the music. Musicians who built the foundation of jazz directly influenced Mingus. His influence has provided the foundation for a great number of jazz musicians who are currently important contributors to the field of jazz. His work with greats like Eric Dolphy, Jon Faddis, and Toshiko Akioshi deserve the same scrutiny as his earlier efforts. This is a difficult undertaking which is best left to a respectful, and thorough scholar, and a task made even more complicated because of how eloquently Mingus’ music expresses itself." Thus, Mingus’s music stretches back to the beginnings of jazz and forward past the avant garde of his day. It stands because of its deep roots, firmly grounded in the history of jazz itself.

Bob Blumenthal's review of Mingus (September 6, 1979), after mistakenly I believe, strongly criticizing most of Mingus’s works in the 1970s, praises Mitchell’s work in these words, which go to the entire purpose of Mingus’s efforts on the album: "Joni Mitchell's record, less hung up on aural appearances, seems a more appropriate memorial to the man. None of the three new Mingus tunes has any characteristic twists and turns. Both 'A Chair in the Sky' and 'Sweet Sucker Dance' offer slightly diffuse ballad lines, while 'The Dry Cleaner from Des Moines' might pass for anyone's plucky blues (but Mingus would surely have approved of such images as 'Midas in a polyester suit'). The supporting instrumentals, filled with soft sound washes and clipped inserts, don't copy Mingus either. Instead, they reflect, quite appropriately, the performing musicians: 'Weather Report,' with Herbie Hancock in place of Joe Zawinul. 'Goodbye Pork Pie Hat,' with Mitchell's lyrics based on the original solos as well as the melody, retains the Mingus flavor, but the bulk of Mingus could pass for pure Joni Mitchell. I doubt that Charles Mingus would have wanted it any other way." Mitchell had helped Mingus achieve what he had set out to do. In turn, he had helped her blaze new directions in pop music. That is exactly what a collaboration should do.

Analysis of the Music

"Music is the mediator between the spiritual and the sensual life." -Ludwig van Beethoven

"Music is a moral law. It gives soul to the universe, wings to the mind, flight to the imagination, and charm and gaiety to life and to everything." -Plato

Among other elements, Mingus’s music included a large dose of African-American church music. In perhaps his most popular and certainly much honored recordings, Mingus Ah Um, Mingus drives his men into the land of gospel music with his “Better Git It in Your Soul.” It was a tribute to soul music, very popular in jazz in the late fifties, and to his own roots in the church. The rest of the album stays in that vein, much of it paying tribute to great jazz musicians – Ellington, Lester Young, and Jelly Roll Morton. Mingus stated that “Bird Calls” had nothing to do with Charlie Parker. Many strongly doubt that statement. Even though Columbia edited the original release to fit it on an LP and also left three tunes off, the album created a sensation as did Mingus Dynasty. However, Mingus refused to record more albums in this vein. He was also one to seek to avoid stereotyping. However, from time to time he did record material that reflected soul roots, such as “Soul Fusion.” Jamie Howson provides an explanation for his refusal to be pigeon-holed: "Mingus was always true to his ever-changing moods: he wanted to create music that, in his words, was 'as varied as my feelings are, or the world is.' For sheer range of expression, his work has few equals in postwar American music: furious and tender, joyous and melancholy, grave and mischievous, ecstatic and introspective. It moves from the rapture of the church to the euphoria of the ballroom, from accusation to seduction, from a whisper to a growl, often by way of startling jump cuts and sudden changes in tempo. Vocal metaphors are irresistible when discussing Mingus. As Whitney Balliett remarked, music for him was 'another way of talking.'” Indeed, whatever Mingus was thinking or feeling was right there in the open. No matter who was pleased or hurt, he did it his way. His best music is in your face and in your heart.

The music on the album Mingus has his stamp, but it is more subtle, takes some time to figure out. There is, indeed, another hand present, another sensibility. As Blumenthal noted in the quote above, that is probably what Mingus wanted. This album is successful fusion. Mingus had been attempting a good fusion album. Mitchell clearly moved into the jazz world, showing she could sing jazz. But she also knew how to work with a group like Weather Report, which was fusion but a fusion group mainstream jazz fans also loved. Herbie Hancock forty years later still can do no wrong whatever he plays in the opinion of most jazz fans.

Joni Mitchell also is a fine lyricist. It was something Mingus needed. Her work on “Goodbye, Pork Pie Hat” is an amazing feat. She caught the essence of Lester Young while fitting words to Mingus’s composition as well as to the original solos. She wrote better than adequate jazz lyrics to each of the other songs. Even the “raps,” the short clips of conversation, are interesting and give the flavor of Mingus in dialogue. Listen to the one discussing when Mingus will die, for example.

The album strikes me as a spiritual one. Certainly, Mingus as one who admired Ellington and grew up in the shadow of the church most likely knew Sonny Greer’s take on Ellington’s spirituality. Sonny Greer in an interview stored at the Institute of Jazz Studies at Rutgers University, Newark, (1974), for example, states that a night at the Cotton Club was "kind of hectic. Harlem was heaven. In those times you had to see that. It was like going to Church. There was a different atmosphere. You could walk up and down the streets all night. There was no molestation. It was a carnival atmosphere . . . Everybody loved everybody. Love is not a new word in our profession."

Love, for Ellington, is the key ingredient in the spiritual. The spiritual must enhance love. It is life-affirming and inclusive. Additionally, however, he was aware of drama and humor in presenting his spiritual message. He is acutely conscious of pacing and the juxtaposition of apparent opposites in telling his tale. He was fond of saying, “A good playwright can say what he wants to say without saying it.” Because Mingus was a great admirer of Ellington, it is not surprising that he shared these ideas and put them to use in his efforts to update Ellington. The key instance of this fact is in the album Money Jungle. Don DeMichael’s 1963 review makes this point clear as well as Ellington’s response: “I've never heard Ellington play as he does on this album; Mingus and Roach, especially Mingus, push him so strongly that one can almost hear Ellington show them who's boss – and he dominates both of them, which is no mean accomplishment." What was captured was the influence of Ellington on Mingus and the difference between the two. Mingus, for example, lived up to his characterization as Ellington’s heir for his ability to surprise with his compositions and arrangements as well as his skill at writing for particular members of his band. On the other hand, his ferocious temper contrasted with Ellington’s calm demeanor. It is fair to say that Ellington’s brilliant playing on Money Jungle is in great part due to the angry energy that Mingus generated. The tension is patent and Duke is not about to let his former sideman, who is one of only three people whom Duke fired himself, get the better of him.

Interestingly, from all accounts, Mingus behaved more like Duke in the making of the album Mingus than like his usual “angry man of jazz.” Obviously, his illness played a role since he was physically incapable of injuring anyone else. However, no temper tantrums seem to be visible, no shouting, no anger. Mitchell seems genuinely touched by him. She wanted to make something that was both personal and mutual, something transcendent. It was to be synergetic, greater than its parts. Mingus also wanted something along those lines. Both artists loved layering in their music, something like a symphonic approach, something greater than its parts.

Again, I think, we are back at Ellington. Again, I think of Money Jungle. Mingus, Roach, the most musical of drummers, and Ellington achieve a layered effect with a trio, also one of Mingus’s points, a small group can sound like a big band. At the same time, Ellington’s points come through; namely, it isn’t what you play as much as what you don’t play that matters. Duke always thought that an artist could say quite a bit without actually saying it. Both Mitchell and Mingus practiced that belief, letting references flow where they may, and hints, letting the listener fill in the blanks. Implications can speak thousands of words and make infinite connections. Silence, Hugh Lawson told me, is the loudest sound, indicating the manner in which Ahmad Jamal uses it.

The similarities between Mingus and Mitchell increase as one goes beneath the surface. Although Mitchell was generally wary of committing to something too early and generally presented a calm, controlled demeanor, she was known for her “stubborn” commitment to her own vision of her music. She also was an adventurer in that music, moving on to new things doing the unexpected, and seeking to satisfy her own musical vision instead of simply seeking popularity. She also hated to rush projects. She took her time to present the best possible version of her vision. That sounds very much like Mingus as well.

Conclusions

Let us skip the “what ifs.” What if Mingus had been well and played with the group? What if more time had been available and Mingus had been able to participate more in the project? The point is that Mingus was dying and had no more time. Mitchell had to finish the project, make the final editing, decide what to do. The point is that her lyrics are right on target. Her singing is the best of Joni Mitchell I have ever heard, and she continued to grow in a jazz vein for a good period of time. She worked happily with superior musicians in a tour and recorded with them. She also brought jazz to a larger audience.

Moreover, the album still draws interest. Those jazz fans who ignored the album when it came out, for whatever reason, tend to be intense jazz fans and snobs. The internet has made it easier to catch up on what we missed. We can dig into things more fully than in the past. Various subscription music sources let us listen to things like Mingus for no extra cost and satisfy the questions: “What does it sound like? Why would Mingus record with a folk singer?” We can also make our judgments without the hard and fast lines that prevailed in the past and reassess our views.

Mingus, indeed, was, like Duke, always ahead of the times. His attempts to reach the misnamed “fusion players” had not been very successful. The musicians were not “fusion players” in the sense that they played only fusion. Herbie Hancock, for example, can play anything, including Mozart and Beethoven. If anything, they are versatile jazz musicians. It is worth remembering that jazz has always been a “fusion music” in the broadest sense. It has taken ideas from all forms of music: classical (Western concert music), African, popular, blues, European pop, and others without limits. It was the first World Music and continues to contribute and take from other forms of music. Nothing is foreign to it, not Mozart nor Mick Jagger. All is of potential use. The music on the collaboration is in itself quite good. If Mingus had lived, yes it is a “what if,” and another album had emerged after Mitchell had a bit more experience as evidenced on her tour and the videos that have surfaced since, the next album probably would have been sensational. However, this one Mingus is quite good.

Mitchell’s lyrics, as stated earlier, capture Mingus’s meaning. This bit from “Goodbye Pork Pie Hat” give some idea of her scope and understanding of what Mingus was capturing in the elegance and humor of Lester Young.

When Charlie speaks of Lester

You know someone great has gone

The sweetest swinging music man

Had a Porkie Pig hat on

She manages to do similar things in each of the music cuts on the album.

I began this work by mentioning the spiritual nature of music in general and jazz in particular. Certainly, this album and the process leading to its creation is a prime example of that process. Her Mingus may not be your Mingus – or mine. However, Charles Mingus obviously had a connection with Joni Mitchell and approved of her version of the multifaceted Mingus. It is a version rich and deep. He approved of what he heard and would have approved of the final product. As Charles McPherson emailed me, Mingus had a wide knowledge of art. He must have heard something in Mitchell that he liked. Theirs was a brief but deep mutual admiration society. That something they found in each other’s music is worth exploring. I have found it satisfying and worthwhile. Many others have as well.

July 2015

From guest contributor Frank Salamone, Professor Emeritus Iona College |