In the 1990s, Bruce Springsteen occasionally performed “In

Freehold,” an unreleased song in which he reflects on

his youth in a small town. Some of the lyrics are nostalgic,

emphasizing that Freehold, New Jersey was the place where

Springsteen “had [his] first kiss at the YMCA canteen

on a Friday night” and played in his first rock-and-roll

band. Elsewhere, he accuses the town of harassing anyone who

happened to be “different, black, or brown” and

not showing much compassion when one of his sisters “got

pregnant” late in her teens. Springsteen’s rapid

shifts from lighthearted autobiography to poetic revenge are

at odds with his usual songwriting practices, but his complicated

view of his small-town origins should seem familiar to anyone

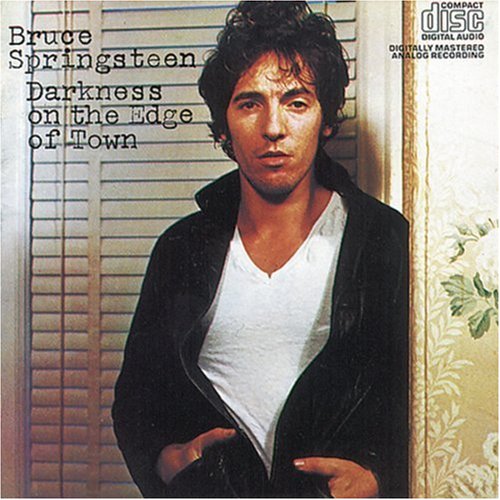

who has listened to Darkness on the Edge of Town

(1978). Throughout that album, Springsteen portrays the lives

of working-class Americans as an endless struggle. Some of

his characters convince themselves to persevere, believing

that better times may arrive in the future. Others chase after

excitement in the present through love, sex, and fast cars.

The album also contains a few traumatized characters who seem

unable to find any sense of purpose.

This article discusses Darkness’s representations

of working-class distress and suggests that the album casts

doubt on the notion that Springsteen’s music “celebrates”

working people. (This reading, which came to light around

the time Darkness was released, is still commonplace

in critical and journalistic discourse about Springsteen.

In A Race of Singers: Whitman’s Working-Class Hero

from Guthrie to Springsteen, for example, Bryan K. Garman

asserts that Springsteen’s career has been, among other

things, a realization of Walt Whitman’s wish to inspire

future poets “who would celebrate the working class

and fulfill the promise of American democracy.” Similarly,

the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette announced in 2004 that

“Rock superstar Bruce Springsteen, whose songs celebrate

the working man, will join Joe Grushecky and the Houserockers

and other local musicians Dec. 2 at Heinz Hall in a benefit

concert...”) Springsteen’s empathy for blue-collar

Americans is unmistakable, but it does not follow that his

principal aim is to praise them. Darkness does not

offer purely positive remarks about “the working man.”

Springsteen’s small towns are complex, and his characters

embody many kinds of anguish and optimism.

Critics have often observed that Springsteen’s approach

to songwriting changed during the time in which he recorded

Darkness. Robert Hilburn interprets the album’s

relatively simple arrangements as a rejection of the Phil

Spector-style grandeur of Born to Run (1975): “Where

Born to Run was mixed at symphonic fullness, the

sound on Darkness was moodier. Songs like ‘Promised

Land’ still featured the dense mix of keyboards, guitars,

and drums, but the solos are short, the players who blew so

lustily on Born to Run are kept in

check. . . . Darkness

is not a recitation of the great party sounds. That would

have to wait until Bruce’s mood changed.” Other

commentators attribute the album’s somber tone to Springsteen’s

frustrations during his two years of litigation with his former

manager Mike Appel. In Dave Marsh’s August 1978 Rolling

Stone cover story on the Darkness tour, Springsteen

worried that his audience was hearing dejection and hopelessness

in his new songs:

It’s the title, [Marsh suggests]. “I know,

I know,” [Springsteen] says impatiently. “But

I put it in the first few seconds of ‘Badlands,’

the first song on the album, those lines about ‘I

believe in the love and the hope and the faith.’ It’s

there on all four corners of the album.” By which

he means the first and last songs on each side: “Badlands”

and “Racing in the Street,” “The Promised

Land” and the title song. He is clearly distressed.

He meant Darkness to be “relentless,”

not grim.

Another interpretation holds that the explosive drums, guitars,

and vocals featured in songs like “Adam Raised a Cain”

and “Candy’s Room” demonstrate that Springsteen

was writing under the influence of Patti Smith, The Clash,

Elvis Costello, and other punk and new wave musicians of the

time. Several critics have also pointed out that Darkness

marks the time when Springsteen stopped writing about

adolescents in abandoned beach houses and dusty arcades. Hilburn,

for instance, writes that the album’s characters are

“men well into adulthood caught up in the now-joyless

rituals of adolescence. Preeminent among these songs was the

stirring ‘Racing in the Street’ . . . The title

and chorus played on Martha and the Vandellas’ ‘Dancing

in the Streets,’ but there was little happiness for

the aging drivers on the dragstrip, or for their forgotten

wives and girlfriends. What’s left after youth and its

passions have gone?”

All of these observations are worth considering, but they

overlook Darkness’s central theme: the struggles

of blue-collar Americans who live in small towns. If you doubt

that the album is a meditation on working-class distress,

read Springsteen’s essay introducing the album in Songs

(1998). In the opening sentence, he recalls that after "Born

to Run I wanted to write about life in the close confines

of the small towns I grew up in.” Then he elaborates

on the subject matter he had in mind:

I was searching for a tone somewhere between Born

to Run’s spiritual hopefulness and ’70s

cynicism. I wanted my new characters to feel weathered,

older, but not beaten. The sense of daily struggle in each

song greatly increased. The possibility of transcendence

or any sort of personal redemption felt a lot harder to

come by. . . . I intentionally steered away from any hint

of escapism and set my characters down in the middle of

a community under siege.

A community under siege – that phrase captures the

spirit of Darkness on the Edge of Town. The album’s

characters are trapped, surrounded by various forms of pressure

that never seem to let up. And while they all feel the anxieties

of small-town life, they respond to those anxieties in a number

of different ways.

The response that probably comes to mind first for most Springsteen

fans is the mixture of determination and hope expressed in

“Badlands.” The words this character uses –

lights out, trouble, head-on collision, caught in a crossfire,

fear, waste – suggest that he feels as though his surroundings

were a combat zone. He seems convinced that his troubles are

inescapable, yet he delivers a high-spirited chorus that pulls

together stoicism, optimism, and slang: “Badlands, you

gotta live it every day / Let the broken hearts stand / As

the price you gotta pay / We’ll keep pushin’ ’til

it’s understood / And these badlands start treating

us good.” Later in the song, the character’s protests

give way to a secular prayer: “I believe in the love

that you gave me / I believe in the faith that can save me

/ I believe in the hope and I pray / That someday it may raise

me above these badlands.” Where does he find this love,

faith, and hope? The question is left unanswered. Springsteen

simply implies that there is something heroic about this character

– he has what it takes to keep moving forward. The same

could be said of the character whose story we hear in “The

Promised Land.” He admits that he feels powerless and

worries that he may be wasting time “chasing some mirage,”

but near the end of the song, in what A. O. Scott describes

as “a climactic vision of purifying destruction,”

he imagines that the future will take the form of a tornado

with the power to blow away his disappointments.

Springsteen’s examination of perseverance becomes more

complicated in “Racing in

the Street.” Early in the song, Springsteen’s

racer, like the drivers in “Don’t Worry Baby”

and “Little Deuce Coupe,” boasts about his success

on the dragstrip:

We take all the action we can meet, and we cover all the northeast

state

When the strip shuts down, we run ’em in the street,

from the fire roads to the interstate

Some guys they just give up living, and start dying little

by little, piece by piece

Some guys come home from work and wash up, and go racing in

the street.

The Beach Boys’ characters keep the focus on their

cars: “I got the fastest set of wheels in town . . .

comin’ off the line when the light turns green / She

blows ’em outta the water like you never seen.”

Springsteen’s racer, by contrast, emphasizes his own

ability not to be overwhelmed by his everyday struggles. His

life sounds exciting – and too effortless for the world

of Darkness – until the third verse. As Hilburn

observes, the racer understands that the satisfaction he finds

in competition does nothing to comfort his girlfriend, whose

unexplained despair causes her to stare “into the night,

with the eyes of one who hates for just being born.”

Suddenly, Springsteen inverts the relationship featured in

“Don’t Worry Baby”: in this song, the racer

seems confident and his girlfriend needs to hear some reassuring

words. Will she hear them? Again, the question is left unanswered.

The racer speaks mysteriously about riding to the sea and

washing away sins, but his closing lines focus on new possibilities,

not necessarily on reconciliation or relief.

For another group of Darkness’s characters,

love and sex provide temporary distractions. The young man

in “Candy’s Room” says a few ominous words

about “strangers from the city” and the “sadness

hidden in [Candy’s] face,” but throughout most

of the song his erotic daydreams force everything else out

of his mind:

We kiss, my heart’s pumpin’ to my brain

The blood rushes in my veins . . .

We go driving, driving deep into the night,

I go driving deep into the light in Candy’s eyes.

She says, Baby if you wanna be wild, you got a lot to learn

Close your eyes – let them melt, let them fire, let

them burn . . .

The character in “Prove It All Night” seems

more easygoing than his counterpart in “Candy’s

Room,” but even he feels the pressures that torment

every character on the album. His curiously old-fashioned

references to pretty dresses and long white bows are apparently

meant to console his girlfriend, but phrases such as you

deserve much more than this, pay the price, and what it’s

like to steal, to cheat, to lie continually darken the

song’s atmosphere.

“Something in the Night” offers a portrait of

resentment, isolation, and defeat. “You’re born

with nothing,” the character wails, “and better

off that way / Soon as you’ve got something they send

someone to try and take it away / You can ride this road ’til

dawn, without another human being in sight / Just kids wasted

on something in the night.”

“Streets of Fire” may be Springsteen’s bleakest

narrative. First of all, the doom-filled organ and slashing

guitar make the song the closest thing to heavy metal Springsteen

has ever recorded. “Streets of Fire” also stands

out because its main character is incoherent. Why doesn’t

he care anymore when the night’s quiet? What does he

mean when he says he’s dying and can’t go back?

His reference to being “strung out on the wire”

suggests that he may be an addict, but he isn’t even

able to make that clear. In one respect, however, this character

is representative of the album in general – he finds

it impossible to explain what has been troubling him. Springsteen’s

characters speak at length about their problems, but their

remarks about the sources of their problems are brief and

laced with abstractions. One character wants to tear this

old town apart. Another wants to spit in the face of

these badlands. A third, forced to settle

for a pronoun, says that it’s never over; it’s

as relentless as the rain. (Marsh suggests that the absence

of clearly defined antagonists on the album may be connected

to Springsteen’s admiration of the 1940 film adaptation

of The Grapes of Wrath: “For Springsteen, the

most striking part of [the film] is the early scene when the

Dust Bowl farmer is trying to find out who has evicted him

from his land and is confronted with . . . images of faceless

corporations. Similarly, a vague, disembodied ‘they’

creeps into songs like ‘Something in the Night,’

‘Prove It All Night,’ and ‘Streets of Fire’

to deny people their most full-blooded possibilities.”)

“Adam Raised a Cain” and “Factory”

begin Springsteen’s emotionally charged sequence of

“father songs,” which would later include “Independence

Day,” “My Father’s House,” and “Walk

Like a Man.” They might also help to account for Darkness’s

preoccupation with the fears and disappointments of working

men. Springsteen’s earliest exposure to working-class

distress was probably his childhood observation of his father,

who struggled to find steady employment and eventually gave

up on Freehold, moving the family (with the exception of Bruce,

who refused to leave his friends and the Jersey Shore music

scene) to California in 1969. The elder Springsteen’s

anxieties, then, could be the underlying model for these songs,

framed by the experiences of a variety of characters. Another

interesting feature of Darkness’s father songs

is that they are not, strictly speaking, about fathers. It

would be more accurate to call them narratives about young

men’s observations of their fathers. In “Adam

Raised a Cain,” the son snarls that his father, like

the father in the Animals’ “We Gotta Get Out of

this Place,” has been cheated out of the best years

of his life: “Daddy worked his whole life for nothing

but the pain / Now he walks these empty rooms looking for

something to blame.” We do not see the father in these

lines; we see the son as he catalogues the ways in which his

father has suffered. “Factory” also portrays a

father’s daily routine as an alarming spectacle. The

narrator watches his father leave home in the morning and

walk through the factory gates. At the end of a shift, he

thinks he can see death in the eyes of the workers. The son

does not comment directly on his father’s way of life,

but the words he chooses to evoke it – fear, pain, someone’s

gonna get hurt tonight – suggest that he despises “the

working life” and has no intention of following his

father’s path.

The title song closes the album with a strong dose of mystery

and ambiguity. The main character seems solitary, determined,

and resilient, but aside from those traits the audience learns

very little about him. How did he lose his money and his wife?

What does he mean when he says he’ll be “on that

hill”? Why, in these soul-searching verses, does he

spend so much time commenting on other people’s experiences?

(They’re still racing out at the Trestles.

They cut their secrets loose or let themselves be

dragged down. Some folks are born into a good life.

Other folks get it anyway, anyhow.) What is “the

darkness on the edge of town”? Is it a place? A state

of mind? What are the things he wants, and why can they only

be found in the darkness? This song, it seems to me, is one

of the most daring moves in Springsteen’s career, a

conclusion in which nothing is concluded. The title songs

of most of his albums – “The River,” “Tunnel

of Love,” “The Ghost of Tom Joad” –

are detailed introductions to some of the themes he wants

to examine. In this title song, Springsteen suggests that

words cannot express this character’s anguish. Part

of what he feels has to reach the audience through the sound

of Springsteen’s voice, his guitar, and his band.

The core of Darkness is a paradox: the album’s

characters are united by the fact that they all feel the pressures

of day-to-day life in small towns, but they are divided by

their responses to those pressures. Thus, to conclude that

Springsteen “celebrates” working people in these

songs is to miss the point. Darkness does not generalize

about the kinds of people Springsteen knew when he lived in

Freehold; it insists that their experiences and temperaments

are as diverse as those of people in any other community.

Springsteen’s commitment to complexity and ambiguity

may help to explain why listeners often find his representations

of small-town Americans even more compelling than those of

talented blue-collar songwriters such as John Mellencamp and

Steve Earle. The resentment of the farmer in “Rain on

the Scarecrow” and the critique of Reaganomics offered

by the disillusioned Texan in “Good Ol’ Boy (Gettin’

Tough)” are staged with clarity and passion, but they

seem two-dimensional, smaller than life, when compared to

the confessions of Springsteen’s characters.

Springsteen’s music has had had a cinematic quality

ever since he included “Lost in the Flood,” “Incident

on 57th Street,” and other story-songs on his first

two albums, but on Darkness Springsteen’s informal

but broad-ranging study of film begins to pay off in a new

way. How do John Ford’s characters feel about their

surroundings in the old West? How do Martin Scorsese’s

characters feel about turning to crime on dangerous city streets?

These questions cannot be answered in a sentence or two. Directors

like Ford and Scorsese choose narrow areas of experience and

then demonstrate how much drama and mystery those strictly

limited spaces can contain. Springsteen began to experiment

with that method of storytelling in the 1970s and has continued

to use it throughout his career. How would you describe the

relationship between the character in “Brilliant Disguise”

and his wife? Is it dominated by love? Suspicion? Confusion?

Shame? What does the character in “The Rising”

have to say about his violent death? Is he wounded by his

separation from his family? Proud that he did his job under

extraordinary pressure with courage and skill? Shaken by the

moments of crisis that made him a victim and a hero at the

same time? Any effort to sum up a “message” conveyed

by these songs would be futile. Like Darkness on the Edge

of Town, they demonstrate that Springsteen’s aim

is to represent experience in convincing ways, not to sing

his characters’ praises.

January 2006

From guest contributor Alexander Pitofsky, Assistant Professor

of English at Appalachian State University

|