|

I was born in a movie house in Brooklyn, New York, in the middle of the twentieth century. I can swear only to the Brooklyn and twentieth century parts. But whatever hospital records say, the movie house part seems equally likely because I grew up with all the common symptoms of delivery in such places. That is to say, I was constantly ravenous for fantasy, knowledge, and exotic horizons while my soul was being warped by the deceptive, my mind polluted by the inaccurate, and my emotions exasperated by the unattainable. Where else could the delivery have taken place?

I’ve gone looking for the precise location of the delivery more than once. Granted it hasn’t been a search with the epic sweep of Roots (or even Forrest Gump), but what’s any personal history without the history part? If the past can’t be retrolude as much as prelude, what good is it? It isn’t only because of the exorbitant price of celluloid without them that old-time projectors had rewind reels. What I have been seeking above all else, I suppose, is the very beginning of the modern expectation process -- the forge where larval hopes and anxieties were turned into contemporary men and women. What I would do once I discovered it I have had no idea. Kiss it as though it were the Blarney Stone? Pound on it as though it were the Wailing Wall? Take a picture of it as though it were the Parthenon? Ironically, I have had no specific anticipations about coming face to face with the fount of all expectation.

Which has been just as well since none of the dozen or more movie houses I inhabited at a weaning age is still open for business. Thanks to streaming, cable TV, DVDs, and other distractions of various computer kinds, fifteen multiplexes now have the task of handling Brooklyn’s 2.3 million residents while once-landmark predecessors not razed altogether have been converted into supermarkets, religious temples, or both. Is this the same borough that, from Bay Ridge to Fulton Street, from Grand Army Plaza to Coney Island, once had its air clotted with the scents of popcorn, lilac aerosols, and backed up toilets? Where there were so many box office windows that cashiers almost outnumbered cops? If Brooklyn hadn’t been the Borough of Movie Houses, it was only because churches and saloons had hired better publicists.

But like it or not, my search for beginnings has had to be concentrated in that most unsettled of ruins -- my memories. The charm of such rubble, of course, is that its every brick can be fondled as a founding stone, a decorative extra, or a precocious awareness precluding the first two. Its curse, when it doesn’t give way totally, is that nostalgic dust can be the hunt's only trophy.

With little choice in the matter, I have been back and forth picking through the debris. I have uncovered nostalgia everywhere, of course, and without desire to apologize for its chalky tonnage. Its impunity has made some detours unavoidable, starting with the Prospect Heights strip of Washington Avenue between Eastern Parkway and Atlantic Avenue where I was raised. While I didn’t know it at the time, the Bell, an oversized living room off Lincoln Place, was a pioneer in offering “art films” -- meaning features produced in Europe about people who either didn’t speak English or had little of interest to say when they did. This was where I found out who Alec Guinness and Laurence Olivier were, wondered why bobbies wore bell-jars on their heads, and developed an itch for going back out into the street and jumping onto the rear of a moving bus. The Bell was also the venue for my father’s once-a-decade jaunts to the cinema, most notably the evening he thought he was taking the family to see Bing Crosby in something called The Anniversary Waltz. He had the waltz part right, but we couldn’t figure out why Bing was wearing a mustache, leering at big-breasted women, and speaking so much French. And what was all that stuff about that actress taking off her corset every other scene to pose naked for a painter? Right, The Paris Waltz wasn’t The Anniversary Waltz. But my father got an hour’s sleep, my mother looked interested in reading the subtitles, and my brother and I couldn’t understand why they insisted on laying the subtitles over the best parts of the actress.

The National, on Washington between Park and Prospect, served as the deep freeze for Saturdays. Well shy of noon, my brother and I were deposited there for three features, a serial, and endless cartoons and coming attractions -- all for ten cents (later twelve and then twenty-five and then sixty, causing mini-riots at the box office with each increase). By the time we staggered out around five o’clock, we had made considerable headway on the Turner Classic Movie channel’s course requirements for Audie Murphy westerns (“Yes, ma’am, one of these days I hope to be able to act”) and Johnny Weissmuller’s Jungle Jim adventures (“Pry my eyes open and point my gut toward the right potted plant”). More than that, we had cleaned the floor with schoolmates, emptied torn seats of their straw filling, and kept on the go between the orchestra and the balcony to elude the gruesome Mrs. Quinn, a flashlight-wielding usher (there had never been anything -ette about her) who had trained for her job at San Quentin.

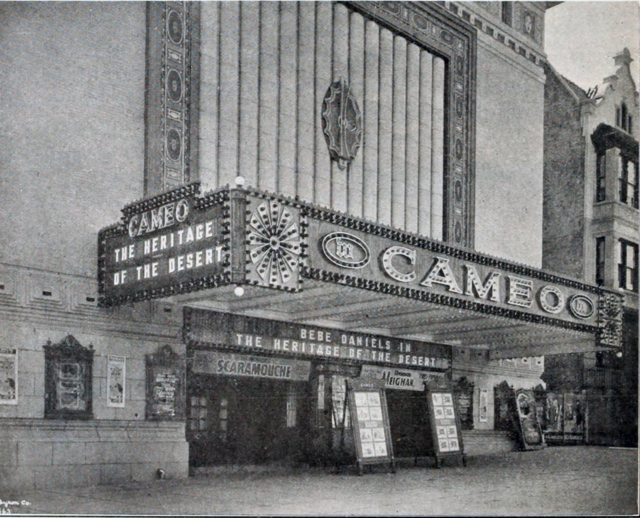

Was there anything except this kind of nostalgia? I remembered, therefore I was; I remembered for others, therefore they didn’t have to be? I had an enormous family of such Shirley Temple (nothing hard inside) memories. There was the uncle, for example, I accompanied to the Cameo (Eastern Parkway) on Monday nights as part of a clan project to keep him out of bars on his day off. He actually stayed on the wagon for the rest of his life, but I doubt it was because of anything we saw at the Cameo together. One picture I recall was The Country Girl, wherein Bing Crosby (again) played an alcoholic so stiffly that my uncle announced to the lobby upon leaving that “any drunk who goes around with a broomstick that far up his ass should stay drunk!”

Another uncle found even more earnest moral lessons to be gleaned in a movie house. He took my brother and me to the downtown Albee to see what he assumed was going to be an innocuous Robert Mitchum war movie, Heaven Knows, Mr. Allison. He was right, it was innocuous -- except that he himself decided upon further reflection that the central situation of a soldier and a nun stranded together on a Japanese-held island required further explanation. So he explained and explained and explained all the way home, along the lines of “Deborah Kerr isn’t a real nun, just an actress” and “Soldiers don’t think of nuns as real women. They think of them as female altar boys with a job to do.” By the time I arrived home, I was resolved to return to the Albee the following weekend to see what I had missed. (Many years later, I told this story to John Huston, the director of Heaven Knows, Mr. Allison, and his response was: “Lad, the thought of anyone sitting through that twice is terrifying. You would’ve been better off listening to your uncle.”)

Another time an aunt took me to see The Jackie Robinson Story at the downtown Orpheum, near BAM. This was no routine outing for her. Although a Brooklyn Dodger fanatic and weary of waiting for the picture to come to a theater closer to home, my aunt was also prone to regarding any place outside her living room as another neighborhood. If she sometimes bowed to the necessity of using a subway, that concession had never really covered getting off stops that opened out onto black sections of the city, such as around the Orpheum. But for all that, we went to see Jackie Robinson playing himself, and on our way home, she declared that sitting in that jammed theater as a decided white minority “must be the way Negroes feel when they go to ballgames.” The Jackie Robinson Story might have been only half a cut above an industrial documentary, but my aunt always thought of it as Do the Right Thing.

And I have always thought of it as more than another nostalgic tale about family members. The fact is that by the time I saw The Jackie Robinson Story, I didn’t regard the Orpheum as more forbidding than any other movie house. They were all intimidating and made me keep reassuring myself that most of the people who entered them eventually walked out again. As with attending Jennifer George’s eleventh birthday party across the hall, the prospect of sheer entertainment should have inhibited a dread of obligation, but never quite did. It wasn’t until I went to the Savoy on Bedford Avenue one day that I began to understand why.

Unlike the tiny Bell and the peeling National, the Savoy preened outside and inside -- serious marquee, chandeliers, all the elaborate light flutes and glitzy Reynolds Wrap on the walls that made people think class. Bordellos were more subdued, souks didn’t have as many thick carpets. Everything but the popcorn was red. Given the ample room between the front row and the screen, the Savoy was also suitable for wrestling matches and the precision firing of candy at the gigantic knees of the actors when the action faltered. Long before he was electrocuted by those dim-witted scientists in the Arctic, for instance, we had put James Arness as The Thing out of commission with black Dots.

But it was also during a lull in one of these assaults at the Savoy that I happened upon a fairly elementary distinction: There were the people up on the screen and there were the people sitting around me in the orchestra. Moreover, one group didn’t seem to have much to do with the other. The people up on the screen were towering icons of glamor, adventure, sleaziness, whatever you wanted. They had enough money to buy anything they wanted, could go anywhere they decided, got everybody on their side before the end. Their one drawback was that they had the life expectancy of a frail mosquito; within two hours at most I was going to know everything there was to know about them, then they were going to be gone, no more tricks to show me. The people in the orchestra -- including parents, relatives, and friends -- seemed to have just the opposite problem: They were as familiar as old shoes, but not even two decades would be enough to figure them out, where they were going to end up, what presents they would get for their next birthdays, what presents they would give me for my next birthday, whom they would marry, how many kids they would have, where they would move, what terrible things would happen to them. Even thinking about what diseases would eventually kill them seemed to make them less finite than the people on the screen because those maladies were highly unlikely to put in an appearance before the afternoon show was over.

What I had found intimidating about movie houses, it occurred to me eons after the first sensation, was that they were theaters of choice -- between the lives spewed out fifteen-feet high and those scrunched into orchestra seats, between the frail mosquitoes flitting through Cinemascope fantasies and the ponderous tortoises crawling toward weekend respites. Like all choices, I resisted it energetically, though maybe not as much as I thought. It was around this time, for instance, that I began to prefer going to the movies alone -- no distractions from friends throwing hats around or sneaking cigarettes or rolling bottles down balcony steps. To myself, I said I wanted to concentrate; what I meant was that I wanted to be in as concentrated form as possible for whatever the Vista Vision reality of the occasion was. I wanted it to recognize me as much as I had set aside time to recognize it. Two hours didn’t seem like much of a sacrifice on its part, not with the ticket prices always going up.

It was within this new one-on-one relationship that movie houses began exerting their real pull on me, and not always to purely aesthetic or spiritual ends. While watching merchant seaman William Holden bob up and down on Alp-sized waves in The Key at the downtown Paramount, for example, I got sick-drunk for the first time (admittedly, after about twenty beers before staggering into the theater). It was while I was watching Glenn Ford in The Man from the Alamo at the same theater that I realized a great existential gap had opened up with two friends who had insisted on going across the street to the Fox to see Our Lady of Fatima. And maybe most of all, there were the one-on-one relationships I established in Park Slope within the Plaza, the only house mentioned here that survived (barely) into the new millennium after going through successive phases as an art film forum, a third-run outlet, a porno cave, a second-run house, and a revival studio. When I began going to the Plaza, it had taken over from the (demolished) Bell as the closest foreign film house to where I lived. Here it was that I had the patience to ignore a noisy popcorn machine that went off every five minutes, met naked women and endlessly talking cops from France, Germany, and Sweden, and encountered a projectionist who was so approximate about the subtitles that he often fixed them on the emergency door beneath the screen, making me wonder why Europeans seemed to talk so much about fire exits. And here it was also that, upon sitting through an Ingmar Bergman film entitled The Naked Night and dealing with carnival performers in the Swedish countryside, that I knew that, whatever I did in life, it would probably have something to do with writing and movies. (Whether I would have been better off aspiring to run a carnival in the countryside is another question.)

But not even my Plaza experiences have satisfied my quest for the source of all expectation. At most, they have reminded me that somewhere along the line I seemed to assume that whatever happened up on the screen was happening exclusively for me, that we had set up a private line between us that the rest of the human race could disturb only by taking too long to shuffle in from the aisle for a seat. Memory has never seemed so limited by having to be after the fact.

By way of compensation (and encouragement to keep searching), I have what happened to me in Rome some years ago. One evening, I was attracted to a side-street billboard announcing the Clark Gable western, Across the Wide Missouri. Since the movie was decades old and Gable had been dead almost as long, I assumed I had stumbled across a revival house. What I entered was a square box of a space that had the smell of a recently evacuated junk shop. Eight rows of hard chairs requisitioned from some cell block had been arrayed before an ancient stain of a screen. There were only two other people in the place -- an Italian soldier on leave who yawned loudly and regularly and an old woman in a shawl who had fallen asleep. Then the MGM lion came on the screen with its trademark roar; it was the last English I heard for two hours.

Most Italian movie houses have been dubbing foreign films since a paranoid Benito Mussolini convinced himself that the United States, England, and France were using film dialogue to smuggle in propaganda against his Fascist regime over the heads of the censors. The practice has survived into the new century mainly because it keeps two important Italian cottage industries (the dubbing business and lazy directors) going. But Across the Wide Missouri, I quickly discovered, had a peculiar problem -- apparently beyond the skills of even Italy’s master dubbers. It was this: In striving for greater authenticity, the makers of the Hollywood epic about nineteenth-century pioneers decided that the Sioux characters played by the Mexican Ricardo Montalban and the Irish-American J. Carrol Naish should speak in that tongue throughout the movie. Equally captivated by the novelty -- or simply unable to find an Italian-Lakota dictionary -- the Italian distributors had retained those lengthy portions of the original soundtrack, so that half the picture was in Italian and the other half in Sioux.

The Italian soldier had a lot of trouble with this, cursing aloud whenever Montalban or Naish had something to say and subtitles didn’t spell out what it was. The old woman in the shawl had no trouble at all because she remained asleep until the house lights came up at the end of the picture. As for me, I had never thought before about what should have been expected from a meeting between a Lakota descended from the Irish peerage who had become famous on radio for playing the immigrant cobbler in “Life with Luigi” and the King of Hollywood who spoke with Vittorio Gassman’s voice. Wherever you were born, life had so many more deliveries.

From guest contributor Donald Dewey

November 2017

|