|

The Indians left little in the Valley – mounds

to be plowed down, arrow heads, the dust of bones. They lived

like

shadows among the trees, like shadows they have passed...

–

Julia Davis, The Shenandoah

What is notable about this early landscape is what it was

not. Absent, of course, were the grand houses of a gentry

class of tobacco planters. Missing, too, was any significant

disparity between the houses of the great and the small....These

were the dwellings of families neither rich nor poor but

all owners of their own land...

–

Warren Hofstra,

description of eighteenth century Valley

Germans,

The Planting of New Virginia

Walking southward into Virginia, having

departed the state that once belonged to it, I follow Highway

340 as it curves

away from the Blue Ridge, compelling me to bid farewell to

the mountains, cast now in the haze by which they are known.

Here, in Clarke County, the road declares itself early and

often, the Lord Fairfax Highway with horse farms, grand and

humble alike, lining the road. Much of the topography, however,

remains the same as in Jefferson County, granting a measure

of geographical understanding to the district’s reluctance

to align – the bitter legacy of a distant conflict – with

West Virginia. Clark County’s economic and cultural

concerns resemble those of the Virginia Valley region, sharing

little with the mountainous Alleghany counties to the west.

So it is that the identities of the places we inhabit and

our own identities are shaped only partially by us, forged

at intervals by forces outside, until the idea by which a

place or we are known appears to others and ourselves, glimpsed

unwillingly in life’s invisible mirror, as things we

never intended them to be.

Why my ancestors passed this way in the direction of the

Smoky Mountains at the end of the eighteenth century remains

a mystery that I may never understand, the clouds that veil

the stars pressed close, unwilling to abate. Perhaps it was

something akin to the dominant reason for their earlier journey

from Pennsylvania to Maryland, namely affordable land and

greater cultural tolerance or isolation. Or it could have

been something completely unlooked for, something averse

to historical circumstance, a reason altogether unlikely.

Dwelling on this question, I realize that my travel based

supposition, my vague feeling that following their route

today might potentially provide answers or insight into their

reasons for going, is perhaps the most ridiculous aspect

of the entire undertaking, for it hinges altogether on the

indistinct and evasive phenomenon of human experience. Whereas

history may hold close her secrets from scholars and scribes,

experience gladly doles out his brutal knowledge, however

grudgingly, to those who, however foolishly, seek him out.

History and experience are estranged lovers, the latter the

event and the former the teller. Both are mysterious and

perhaps ultimately unknowable, but that is precisely what

makes them so seductive, both to each other and to us. The

Spartan general lies dying on a field of battle 2400 years

ago, perhaps wondering who will tell his story and recall

his glory or dishonor, while the fragmentary data left in

his wake fascinates the young historian, centuries later,

hunched at a desk, in search of lost time, trying to make

sense of, or even imagine, a place and worldview so far removed

from hers that it might be considered alien. As the French

poet Paul Valéry warned, "History is the most

dangerous concoction the chemistry of the mind has produced.

Its properties are well known. It sets people dreaming, intoxicates

them, engenders false memories, exaggerates their reflexes,

keeps old wounds open, torments their leisure, inspires them

with megalomania or persecution complex, and makes nations

bitter, proud, insufferable, and vain. History can justify

anything you like. It teaches nothing, for it contains and

gives examples of everything." Hardly an endorsement

of the discipline. Yet, for all this, for all history’s

faulty detours and dead ends, agendas and distortions, illusions

and compulsions, historians have ever echoed the Roman historian

Livy in ultimately deeming "antiquity a rewarding study."

Passing one of the smaller rural homesteads along the road,

I hear an abrupt bark from the shade of a large oak, followed

by the swift advance of a large, black and tan dog. It barks

as it lopes, tail up, bearing down upon me with bounds and

growls. Rather than running, I loose the straps of my backpack

and pull it around before me, holding it, elbows bent, as

a shield, however ineffectual it might prove to be. When

the canine, a well-fed doberman, gets within a few paces,

he stops and dances from side to side, an inimical jig without

music, save the barks he continues to hurl at me from deep

within his throat. I gradually continue to advance down the

road, backing, talking softly to the dog, remaining as still

as possible, while trying to work my hand into the top end

of my pack. After a few seconds of digging, I find the zipper

to the tent pack and am able to pull free one of the folded

fiberglass tent poles, hard to break and, when wielded, capable

of inflicting intense pain on the sensitive end of a dog’s

nose. The doberman follows but seems content to merely dance

and bark. Watching it, I remind myself that this is no feral,

rabid thing, but a fat domestic with a leather collar, dangerous

to be sure but a creature that someone surely feeds and dotes

upon, probably used to chasing the rare cyclist or wanderer

who appears along his portion of the highway. Perhaps sixty

feet down the road from the place where our confrontation

began, the dog slows as I continue to fall back and then

stops altogether, though its eyes remain fixed on me, its

barks becoming intermittent. I retreat a few more feet and

then turn and continue, the tent pole slipped back into the

pack, the pack reunited with the sweat on my back, torso

and shoulder straps reluctantly tightened. A few paces later,

I glance behind me to see my potential assailant turned away

from me, watering a sign post, leg cocked. He completes his

marking, kicks up some loose gravel with his hind legs, and

trots back down the roadside toward his shady tree, tail

high with pride, identity intact, victor of the conflict,

lord of his territory once more.

On this day, Berryville is a quiet, peaceful town. Sitting

in the cool corner of a shaded parking lot, hiding from my

loyal fellow traveler, that persistent late summer sun, and

drinking from a cold twenty-ounce can of beer, I see the

area as the kind of place where folks are forced to make

their own fun but are probably altogether happy and content

to have things that way. Yet, as with many other places,

this was not its nature more than a couple of centuries ago,

the parochial visage of the mature present grown drowsy and

somber in the wake of youth’s primal howl. Originally

laid out in 1798 as Battletown, the village would alter its

name later in tribute to its swashbuckling crossroads innkeeper

and gamesmaster of the mid-eighteenth century, Benjamin Berry,

who had constructed on his tavern’s front lawn, not

far from where I am sitting, both a bear pit and a fighting

ring, in which he was fond of pitting men or animals against

each other in the hopes of drawing a bloodthirsty crowd,

which he calculated, accurately it seems, would soon seek

refreshment at his inn. Set along this well-traveled road,

the place was ideally situated to attract fresh combatant

and naive victim alike. Among the more storied fighters to

pass through Berry’s ring was a young Daniel Morgan,

then a hard-drinking wagoneer, who bested local champion

Bully Davis in a punishing, bar-wrecking melee of more than

an hour’s duration, which would lead to a rematch several

months later that quickly dissolved into a free-for-all involving

the entourages and friends of both Morgan and Davis, as well

as the more than one hundred spectators who had come to witness

the contest. Eventually Morgan’s contingent was victorious

and the festive rowdies, stoked by blood and thirst, rushed

Berry’s tavern en masse, much to the innkeeper’s

delight.

Departing the placid Berryville of the now, falling in with

the sun once more, I am reminded of how ours is an ongoing

savage history – in spite of the entitled sense of

progress for which we congratulate ourselves – one

we continue to exact upon each other as well as the creatures

of the world we live in. The latter transgression has always

seemed to me the more heinous since the animals who suffer

at our hands cannot understand the material, abstract, or

perverse human motivations that orchestrate their agonies.

I think of the doberman who had pursued me, wondering if

he had been encouraged or trained to go after every foreign

thing that approached his owner’s domain. Then my image

of him, dancing back and forth, nape hair raised – nature

made over again by dream – dissolves into that of another

such dog encountered years before, beneath a roof of corrugated

tin in a nineteenth-century red brick warehouse converted

into a dirty, hot gym, the concrete floor covered in dust

and vague stains, the old steel equipment, nearly all of

it, wearing a thin coat of orange rust. This grimy place

of low grunts and sweaty bodies was owned by a semi-professional

football player who also worked as a bouncer and dabbled

in drug-dealing and dog-fighting. He was, however, for all

these things, not a completely terrible fellow, inquiring

after your health and freely offering his mostly hard-earned

knowledge of the human body. Following him about the dark,

ill-lit building – clammy in winter, ovenlike in the

warmer months – was a massive three-legged doberman,

his absent hind appendage mangled and amputated in the wake

of some ill-fated distant contest. Yet, despite the needless

cruelty to which he had been subjected by his owner, the

dog remained loyal to him, ever at his side, a bane to any

who might threaten him and altogether terrifying to many

of the unoffending weightlifters. On one particularly hot

afternoon, not unlike the one I find myself walking in now,

as I lay on a rusty bench, pressing weight from my chest,

I felt a sudden heavy pressure on my right thigh. Returning

the weight bar to the steel frame above my head, I half-rose

to find the three-legged doberman resting its head on my

upper leg, its brown eyes fixed on my own in that strange

imploring glance of companionship peculiar to dogs. Sitting

up, I patted the dog’s head and rubbed his ears until

he wandered away, probably in search of his master.

The Catholic thinker Saint Thomas Aquinas believed that animals

have no souls. One need know very little about them or theology

to be certain that Aquinas was dead wrong; yet for all our

science, our understanding of dogs and other animals remains

so limited as to render our knowing indistinct – the

knowledge of the other blurred by our preoccupation with

ourselves – our focus fixed closely on our side of

the relationship, our own perceptions – and molded

by the limited collective assumptions of the time in which

we live. Of course, arrogant hypotheses and the uninformed

conclusions that inevitably follow them are not restricted

to our relationships with animals or our own time. While

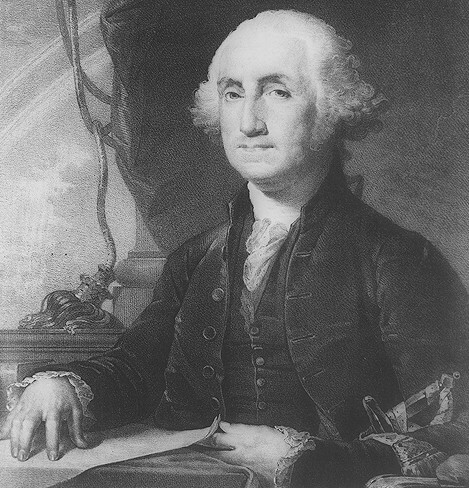

traveling with a survey team in the area of Frederick County,

the district into which I soon will be passing, in the spring

of 1747, a sixteen-year-old George Washington noted that

the inhabitants "seem to be as Ignorant a Set of People

as the Indians. They would never speak English but when spoken

to they speak all Dutch." Preoccupied with the importance

of his English-speaking survey party, this precocious teen

insists that the German settlers he encounters naturally

should resort to his native tongue, attributing their reluctance

to an inherent Indian-like ignorance and declining to entertain

the possibility that they may have been speaking their own

language out of preference, perhaps even in order to talk

undetected about Washington and his companions. Washington

also neglected to perceive his ignorance of the language

as a personal failing, a symptom of his own incomplete knowledge,

but then he was, after all, only a boy; and, reminding myself

of this, I recall, all too clearly, the thick-headed prejudices

of my own teenage years – that dynamic self-obsessed

period in which we wish irrationally for other things, both

possessions and circumstances, and believe we are privy to

all answers, while the world about us responds too slowly.

It is a phase of development that, unfortunately, fewer and

fewer people of our own time appear willing or able to outgrow.

Approaching Winchester, the town to which Daniel Morgan retired

when his days of brawling and soldiering were done, I perceive

against the western horizon Little North Mountain and Great

North Mountain, eastern outcroppings of the Alleghanies,

the great chain of peaks stretching northward into Pennsylvania

and on toward the Catskills. Having longed for mountains

since departing the Blue Ridge, I am struck by an indistinct

reassuring comfort that accompanies their appearance. John

Esten Cooke, born in Winchester in the first half of the

nineteenth century and destined to witness the monumental

carnage of that century’s, our nation’s, most

tragic conflict, serving in the Confederate army, felt a

comparable solace at the prospect of these hills: "I

know not how it is with others but to me all sorrows and

heart-sinkings come with far less poignancy amid the fair,

calm, silent mountains." Cooke, perhaps possessed of

some vague inkling of what bloody events lay ahead for his

home and himself, also associated mountains with "the

great mist-shrouded future," the nature of time as yet

unfolded, obscured by the mist that hangs from the hills,

resting softly on treetops. Greeting the Alleghanies and

thinking of Cooke, I wonder what they may hold for me.

Upon crossing Opequon Creek into Frederick County, I begin

a long, gradual ascent toward Winchester. Whereas the Alleghanies

had introduced themselves remotely, above the horizon in

the distance, Interstate 81, an immense road that will shadow

me throughout much of my journey but that I hope to avoid

as much as possible, appears for the first time below me,

beneath a highway bridge I am crossing. The massive travel

artery that replaced Route 11, which in turn had developed

out of the wagon road grown out of Athowominee, 81 is a swarm

of gaseous wind, speed, and thunder, trucks and cars interweaving,

packed close, hurtling toward ends and destinations I cannot

guess. Though possessed of a generous median and wide roadside

shoulders, the large thoroughfare is banned to foot travelers;

probably for their own good, but there are places to the

south – if I get that far – where it merges with,

or rather absorbs, Route 11, places where I’ll find

myself reluctantly tracing it, or, without much regret, passing

along an alternate route.

The strip malls and businesses that appear with the interstate

feel claustrophobic after so much walking in the open, amid

agricultural land and the occasional residence. Yet, these

are appropriate enough sights to greet me as I enter this

place founded and perpetuated on commerce. In 1789 André Michaux

described Winchester as "a little town whose Trading

with the Settlements of Kentucky is done by land. The merchandise

comes from Philadelphia, Alexandria and particularly from

Baltimore." A cog in the machinations of westward colonial

distribution, Winchester was a place to buy, sell, and haggle – to

empty the wagon or resupply, depending on your needs. One

notable local merchant whose trade had far-reaching influence

was the German gunsmith Adam Haymaker. Following the European

German tradition, early gunsmiths in North America had crafted

high-caliber flintlock rifles for the purpose of felling

animals as large as a mature black bear. However, soon realizing

that mobility, and therefore considerations of convenience

and weight, were of the essence given the circumstances of

travel, guncraftsmen like Haymaker began engineering smaller

barrels and stocks, maple and black walnut being the materials

of choice for the latter. By the second half of the eighteenth

century the typical gun was a .36-caliber rifle, usually

fixed with a bayonet for the purposes of possible Indian

engagements or finishing a kill. The weapon was lighter,

more accurate, and required less powder.

Beyond colonial Winchester, we need look no further than

the multi-million dollar military-industrial complex of today

to see that weapons and commerce have always gone hand in

hand in the United States, and are still going strong, the

path to economic development cleared through military might,

though the terminology changes slightly, the bluntness of

Manifest Destiny having given way to fuzzy linguistic blankets

such as Nation Building. It is a small semantic irony too

that a century or so following the improvements Haymaker

and others brought to the North American rifle, a gun called

the Winchester, developed by a New Yorker named Oliver Winchester,

would come to be lionized as "the gun that won the West," its

repeating rounds introducing a new deadly quality into firearms

combat. Like other such technological innovations of war,

the Winchester was an implement of dehumanization as well

as progress, both in terms of the way it impersonally vanquished

those who opposed its wielders and the unconscious toll it

could exact on those very wielders, as well as the people

involved in its creation. Having come to believe her family

haunted by the restless ghosts of the thousands cut down

by her husband’s rifle, Oliver Winchester’s wife

Sarah would flee, shortly after his death, from New Haven,

Connecticut, to San Jose, California, where she would use

her husband’s lucrative industry profits to construct

indefinitely an elaborate, one hundred and sixty room mansion,

designed haphazardly with the help of a spiritual medium

in order to accommodate the angry ghosts seeking vengeance

upon her. As the family necromancer explained to Sarah, "You

can never stop building the house. If you continue building,

you will live. Stop and you will die." A Rasputinesque

hoax perhaps, yet I wonder if modern psychology could have

offered Sarah any greater measure of peace, the lives extinguished

by her husband’s invention having come to be the sole

fixation of her own.

Lost amid these musings, I discover that I myself am lost,

literally, in Winchester, wandering in a residential neighborhood,

evidently having missed the signs that would navigate me

through town and onto Route 11, the street I am walking along

devoid of a number, bearing an unfamiliar name. Though curious

at my misstep and apparent inattention, I am not especially

bothered, having found that most people in towns and small

cities – at least in this part of North America – usually

are willing, if not happy, to give directions. As John Steinbeck

noticed decades earlier, "The best way to attract attention,

help, and conversation is to be lost. A man who seeing his

mother starving to death on a path kicks her in the stomach

to clear the way, will cheerfully devote several hours of

his time giving wrong directions to a total stranger who

claims to be lost." Though I have never attempted Steinbeck’s

strategy of merely purporting to be lost, his point about

direction-givers appears mostly true. Asking directions at

the next convenience store, I am not only told where to go

but actually taken there by a carload of friendly female

students from Shenandoah University, a local college somewhere

nearby. Sitting in the backseat of the car, trying to soak

up the air conditioning, my voice sounds to me both tight

and sluggish as I converse. Only later, after I am dropped

off, do I realize that these are the first people I have

talked to at any great length in days.

Since the outset of my journey, I have heard fragments of

numerous voices, but used my own very little, though this

silence is partially by design. Many scribbling wanderers,

especially the journalistic variety, go out of their way

to talk to as many people as they can, seeking out, sometimes

obtrusively, county officials and influential community people

on the one hand, and those they believe to be the local downtroddens

and deviants on the other, ostensibly hoping to arrive at

a kind of voyeuristic sociological montage of the community

at hand. Yet the people on the other end of these questions – rich

and poor, educated or not – usually divine exactly

why they are being questioned, often because the traveling

interlocutor readily and proudly volunteers his purpose and

aim. As a result, the people at hand frequently offer only

embroidered images of their lives and places – appropriately

fabricated responses to forced, synthetic questions. I wanted

to avoid a lot of that if possible. I knew I was passing

through the environments and spaces of others – their lives and places – and to actively seek some kind of

connection seemed artificial and presumptuous to me. My attitude

was that it would come to me or it wouldn’t, and that

whatever did arrive of its own accord would be far more interesting

and authentic than anything I might actively seek out. The

philosopher Buber went fundamentally further, asserting that "the

depths of the question about man’s being are revealed

only to the man who has become solitary, the way to the answer

lies through the man who overcomes his solitude without forfeiting

its questioning power." Though the twenty-first century

human of the United States finds himself wholly interconnected

on the literal, technological level, his fundamental personal

state remains significantly cloistered by the very economic

and industrial forces that connect him, in the abstract,

to the rest of the world. Remoteness then is not something

most of us have to work at very hard in order to achieve.

As the poet Rilke maintained, aloneness "is at bottom

not something that one can take or leave. We are solitary."

So I feel myself passing more like a ghost, transparent as

the wind, a walking stranger in the night or the day, there

and then gone among places and people. It encourages me too

that the first European to enter the Shenandoah Valley, John

Lederer, traveled in much the same way, treating with the

Indians only when invited to do so and remaining ever silent

and courteous at the strange things he witnessed, most of

which he did not understand and could not hope to explain

or even portray – foreigner to a land that did not

know him, one of great mysteries. The poet W.H. Auden said

of the wanderer in his poem of the same name, "Ever

that man goes through place-keepers, through forest trees,

a stranger to strangers."

The kind Shenandoah students have dropped me off near a local

high school on Route 11, a road known also as the Lee Highway

and the 11th Infantry Regiment Highway, the history of human

conflict asserting itself again in these memorial dedications

to distinguished American soldiers of the past. A site of

strategic geographical importance in eighteenth century North

America, Winchester was destined to accommodate its share

of military personalities. At the beginning of the French-Indian

War, long before the town had become a great trading center,

Colonel George Washington, having negotiated his teenage

years and passed into early manhood, came to the area with

orders to raise and train a militia, which in time would

effectively transform the village into a kind of garrison.

However, even as the newly-constructed Fort Loudoun (named

by a grateful Colonel Washington for the British general

who armed the fort and afforded him the legal authority to

hang militiamen for disciplinary infractions) loomed over

the town with its two-hundred-and-forty-foot walls set atop

a hill to the north on an ancient burial ground, the basic

lack of discipline among young Washington’s charges

and the imperative need for readiness forced him to resort

to draconian methods in literally "whipping" his

men into shape. Profanity, for instance, brought twenty-five

lashes from the cat-o’-nine-tails, feigning illness

fifty, and drunkenness a hundred. Although whipping post

justice was not new to Winchester – in the mid-1740s,

for example, a girl received twenty-five lashes for bearing

an illegitimate child – the offense of drunkenness,

despite the harsh penalty, remained particularly prevalent

and difficult to stop since locals had developed as a prosperous

side-racket the selling of gin and liquor to Washington’s

men. Late in the summer of 1756 the young colonel threatened

the townspeople not to allow "the Soldiers to be drunk

in their Houses, or sell them any liquor, without an order

from a commissioned officer; or else they may depend Colonel

Washington will prosecute them." For all this warning

and intimidation, threats and whippings in some cases were

not enough. In one particular instance, two men were hung

from a newly-constructed gallows before the town, shortly

after the arrival of a group of new militia recruits – a

spectacle Washington felt would "be good warning for

them."

It is odd to think of young Washington, for whom so much

destiny and distinction still lay in wait, chiding and bullying

his men and the townspeople, frustrated at their stubbornness,

their lack of fear in the face of verbal and physical intimidation,

their indifferent stoicism and strong will when punishment

was visited upon them – though it would be these same

traits that eventually would transform many of them into

fine soldiers and, if they managed to live into the 1780s,

archetypal Americans. Odd too that on the site of an old

Shawnee camping ground Washington was training a force to

help bring about that tribe’s destruction, history – even

when rooted in a single place – steadily moving toward

the next conflict, the next seizure and occupation: the traces

of the conquered buried along with their culture, the conquerors

having begun already the unconscious journey toward their

own indefinite downfall, the vague legacy of the defeated,

departed and approached again.

I am glad to get out of Winchester, although the sprawl that

emanates from its center makes it difficult to say exactly

where it really ends. I do not really feel the Valley either

until Winchester is left in my wake, the topography revealing

itself again, less impeded and concealed by the deeds and

constructions of humans. A long strand of low rich land stretching

northeast and southwest, the Shenandoah Valley lies cradled

between the Blue Ridge to the east and the western Allegheny

Mountains, their name drawn from an Indian word meaning "Endless." Because

the Shenandoah River flows north, general directional travel

references are reversed here: heading south as I am is referred

to as "going up the Valley." By the eighteenth

century, few Indians inhabited the region, though they still

passed through frequently on hunting and trading expeditions.

When European settlers arrived, parts of the Valley already

were open with meadows that could be converted easily enough

into agricultural fields, their openness a result of those

periodic Indian burnings, purposeful land-clearing forest

fires, not unlike those employed by foresters today, set

to facilitate crop growth and attract game.

Nearly all of the early forest that remained in the Valley

would be cut by settlers. This while resting beneath, enjoying

the shade of, its most common tree, then and now: a modest

roadside white oak, this particular one perhaps half a century

in age, its bottom branches hanging so low I can brush the

tips of the leaves with my fingers while sitting on the ground,

my back against the trunk. Writing in 1796, Isaac Weld Jr.

noted at great length the already palpable development of

the Winchester area in the context of the still largely uninhabited

Blue Ridge:

In the neighborhood of Winchester it is so thickly settled,

and consequently so much cleared, that wood is now beginning

to be thought valuable; the farmers are obliged frequently

to send ten or fifteen miles even for their fence rails.

It is only, however, in this particular neighborhood that

the country is so much improved; in other places there are

immense tracts of woodlands still remaining, and in general

the hills are left uncleared.

The wilderness transformed into plentiful fields, wheat became

the dominant crop in the Valley during the second half of

the eighteenth century and would remain so for more than

a hundred years. There are fields of it even now, grown from

verdant green nubs into swirling wind-blown oceans, golden

with new grain. Both during the American Revolution and decades

later, when Virginia seceded, it was the Valley that provided

bread and forage for its armies and horses, though great

fields of hemp were cultivated as well in the time of the

former conflict, primary material in the making of rot-resistant

rope and paper.

For all the transformations humans have inflicted upon the

Valley, it remains even now an altogether spectacular visual

landscape, framed by ancient mountains and drained by the

numerous rivers and creeks that ever enrich and refresh its

soil. In his own time, Weld too was struck by the beauty

of the landscape, celebrating in particular the special appeal

of those venerable trees fortunate enough to have been spared

the axe:

The hills being thus left covered with trees is a circumstance

which adds much to the beauty of the country, and intermixed

with extensive fields clothed with the richest verdure, and

watered by the numerous branches of the Shenandoah River,

a variety of pleasing landscapes are presented to the eye

in almost every part of the route from Bottetourt to the

Patowmac, many of which are considerably heightened by the

appearance of the Blue Mountains in the background.

Though the Valley is much changed, there remain places where

Weld’s visual description is as accurate now as it

was over two centuries ago, much of the land still farmed,

rolling – laying well, you might say – and most

of the visible Blue Ridge clothed in dense forest, huge tracts

of it owned and preserved by the federal government.

Along the highway again, passing over Opequon Creek, a body

of water I’d already encountered once, I am reminded

of the well-known expression by the ancient philosopher Heraclitus:

that one cannot step into the same river twice. Though bearing

the same name, the Opequon beneath me is, for all practical

purposes, a disparate body of water – fed by different

streams, containing a variant water chemistry – from

the one I had crossed to the north. So too both it and the

whole Valley are vastly different entities within their respective

identities from what they once were in the past – though

each occupies the same geographical position and may appear

in places similar. I remind myself of this condition from

time to time: that this is merely, and can only be, despite

the occasional temptation to imagine it otherwise, the Valley

of my own era.

More discernible and easier to keep in mind, since they are

ever before and beneath me, are the changes to the trail

I am following: this highway of asphalt, concrete, and rock

that once was Athowominee, a muddy footpath, overgrown in

places by weeds and grasses, only cob webs and sapling branches

to greet the face of the infrequent traveler. In the wake

of the French-Indian War what had been a modestly-traveled

wilderness path for Indians and, increasingly, frontier settlers

was widened and graveled in an effort to make wagon travel

easier. Local counties generally shouldered the expense,

though the funds they put forth generally came back to them

or were surpassed as a result of increased travel and commerce

along the route. In addition, it was local farmers who performed

the labor in the winter months or during the slow time between

planting and harvesting. Thus, much of the money expended

went to local residents and, by extension, back into the

county economy.

Above the village of Stephens City, originally Stephensburg,

I climb a plateau where I can see the Blue Ridge and Alleghanies

off in the distance on either side of me, a perspective that

affords a kind of context both for the Valley and my place

in it. Unfortunately, the prospect also affords a clear view

of 81, the large multi-wheel trucks, the size of toy models

at this distance, dwarfing all other traffic. Though I dislike

the appearance of the interstate, I am glad it is there for

the purposes of my labors, the thought of all that traffic,

all those massive trucks, crammed onto Route 11 not a very

pleasant or practical one. Of course, long ago the route

had accommodated a significant portion of the overall commerce

in the North American colonies. Instead of long lines of

trucks, the late-eighteenth century traveler would have encountered

herds of livestock – cattle, goats, sheep, pigs – being

led to market, either in the nearest town or perhaps even

to the great livestock capitol of Philadelphia. Other essential

merchandise – salt, sugar, medicine, tools, gunpowder,

manufactured goods – was transported either by wagon

or packhorse train. And then there would have been the locals,

walking or riding to work or church, and the far-bound settlers,

afoot or perhaps sitting amid their possessions in Conestoga

wagons. Ironically, many local folk then felt the same way

about Conestogas as modern travelers do regarding tractor

trailers, the wagons’ heavy bodies and wheels creating

deep ruts and mushy holes when the ground was wet and huge

clouds of dust in the arid heat of late summer and early

fall. Just as massive truck tires explode and litter the

highway, so wrought iron nails would shake or jolt loose

from the wagons, dropping to wait unseen in the dirt for

an unsuspecting traveler – perhaps the next barefoot

farm boy, sent to town for a few grams of salt or sugar,

maybe, if he was lucky, a piece of hard candy for himself.

Late afternoon, shadows long, grass already dampening, resting

before I strike the tent, having received permission to camp

at the edge of a pasture, I hear a cow bell in the distance,

and, closing my eyes, try to imagine, as best I can, this

time of day for those distant travelers who passed this way

before me. Along the road, in the fields, amid the gentle

dusk of a Valley summer, the packhorse and wagon teams unhitched

and hobbled, the long day’s sweat and imprint of harness

thoroughly scrubbed away from the horses’ flanks by

the attentive human master for whom they constitute a livelihood.

With bells placed about their necks, they wander deeper into

twilight, grazing, until darkness fills the Valley and the

drowsy traveler, laid out beside a fire or stretched on a

straw mattress in or beneath his wagon, can no longer see

them. Yet this does not trouble him as he gradually succumbs

to slumber amid the damp grass and all his worldly goods,

for across the field there drifts, lighter than air, a kind

of lullaby of wind chimes: the soft tinkling of horse bells.

However we modern individuals might choose to imagine it,

traveling was no romantic matter for drovers and wagoneers,

the livestock and goods they managed a necessary hindrance

and burden ensuring their ability to set food before their

families. Bent on speed and efficiency, they would have carried

little else with them beyond their goods, the bare minimum – an

essentialist mentality that still exists today for those

who happen to travel long distances on foot or horseback.

Next day, wandering here along the road, my wagon on my back – a

forest green Lowe Alpine backpack of polyethylene foam, roughly

a foot across and two feet in length – contains everything

I deem necessary on a daily basis, though even an experienced

hiker may discover over the course of his journey that he

is carrying things he really does not require, in which case

they are usually left behind, given away, or mailed home.

Subtracting weight from a pack is a fundamental and persistent

objective of all wanderers since it increases comfort and

ease of movement while lessening the unrelenting strain upon

the back and knees. Along this road, my own material existence

is reduced to a two-pound tent, summer-rated light sleeping

bag, foam pad, lightweight battery-powered headlamp, small

flashlight, stove and one-liter fuel bottle with cook pot,

Kabar knife, three twelve-ounce plastic water bottles, one-ounce

bottles of disinfected rubbing soap and sunscreen, half-roll

of toilet paper, small stainless steel bowl for both drinking

and eating, dried fruit, meat, and garlic cloves (to deter

insects) in ziplock bags, clay pipe and tobacco pouch (a

nonessential vice), bandana to keep the sweat from my eyes,

a white cotton shirt, one pair of shorts, underwear, one

pair of liner socks and two pairs of wool socks, wool pullover,

rain pants, poncho, moleskin one-ounce bottle of hydrogen

peroxide, and a jackleg collection of road maps for Maryland,

West Virginia, Virginia, and Tennessee, torn from their travel

books and held together by a plastic, as opposed to metal,

paper clip. Everything else on my body, worn and in use.

Perhaps such lists can only appear mundane, mere corporeal

distractions from greater abstract purposes. On the other

hand, it may be closer to the truth that they, the visceral

and the mental, are intertwined, perhaps even hopelessly

tangled. Among all the world’s thinkers, probably it

was the philosopher Spinoza who pursued most doggedly the

confluent nature of mind and body as mutual determinants

of human existence. In fact, as my journey unfolds, I find

my bodily needs and mental musings increasingly overlapping

and giving way to one another: the mind that hungers in the

monotony of travel, the body that wonders in the midst of

its fatigue. To be sure, there are times when I wish for

additional equipment or information, as well as various other

things, but these desires eventually give way to the more

perspectived and abstract observation that I generally have

with me, amid this twenty-five to thirty pounds of mass on

my back, all I really need. Obscured, or rather drowned out,

by conditioned cultural and corporeal concerns, this brand

of thinking – a kind of applied minimalism – comes

to twenty-first century Americans with great difficulty,

ours being an unprecedented arcane culture of wealth and

excessive ownership, the frivolous objects in our basements

and the ever-appearing, labyrinthine roadside storage complexes

hardly necessary to our existence.

By and large, such gluttonous consumption would have been

foreign to the local residents of over two centuries ago – homes

small and spare, possessing for the most part, only what

they made or grew – though there were notable exceptions.

Leaving the area of Middletown, I pass the opulent limestone

estate Belle Grove, built in 1797 for Major Isaac Hite (Heydt),

a descendant of German immigrants from Alsace who attended

the College of William and Mary and served in the American

Revolution. In 1731, Isaac’s father, Hans Jost Heydt,

had bought ten thousand acres of land in the Valley and led

a party of German families down Athowominee from Pennsylvania,

onto Maryland’s Monocacy Road and over into the Shenandoah.

Though Jost did not own slaves, his son, years later – grown

immensely wealthy through the gradual, efficient, and lucrative

sale of his father’s real estate – eventually

would come to have in his possession more than a hundred,

a bizarre anomaly in the region. As Isaac Weld Jr. summarized

in 1796, "On the eastern side of the ridge cotton grows

extremely well; and in winter the snow scarce ever remains

more than a day or two upon the ground. On the other side

cotton never comes to perfection; the winters are severe,

and the fields covered with snow for weeks together." Furthermore,

with a few exceptions, the nights were too cold in the mountain

and valley region of Virginia for cultivating the less hardy

variety of tobacco grown at the time. This and other environmental

variations between western and eastern Virginia, along with

the inherent cultural differences among western settlers

and the Anglican planters of the east, conspired to make

the slave plantation an oddity and the African-descended

population extraordinarily sparse, though it would grow steadily

in the decades leading up to the Civil War. Frontier Germans

in particular took pride in their independence and self-sufficiency,

developing small farms that could be run efficiently by the

family with occasional help from neighbors during episodes

of construction, planting, and harvesting. These lifestyle

differences from eastern Virginians eventually voiced themselves

through legislation. With the aid of lawmakers like Jefferson,

western Virginians – the more numerous Scotch-Irish,

as well as the Germans – increasingly pushed for greater

influence in government, ultimately disestablishing the Anglican

Church and abolishing the laws of primogeniture and entail,

which they generally viewed as decadent and unfair.

The influence of the east, however, with all its benefits

and evils, did penetrate certain portions of the Valley:

on the rare large plantation like Hite’s and around

Winchester, where nearly everything could be sold or traded,

including the labor of slaves and indentured servants. Frontier

Germans were especially unlikely to own or acquire slaves

as a result of their religious convictions, economic frugality,

and their own recent vivid experiences with thraldom. Coming

to North America, families that had fled the Germanic states,

including my own ancestors, would have endured a hellish

six to eight week passage across the Atlantic from Hamburg

or Bremen. Despite the terrible conditions they had lived

under in the Palatinate, few were penniless when they departed

their homes and the southwestern Germanic states were among

the least feudalistic, meaning some individuals actually

had owned their land. However, all but a few were quickly

exploited out of whatever money or possessions they might

have had on them. Frequently, they were purposely detained

at ports while local merchants orchestrated a practiced racket

of gradually sucking dry whatever money they had brought

with them. Once onboard, their goods were often looted by

the crew as their physical health began to diminish in an

environment highly conducive to malnutrition and epidemics.

As Gottlieb Mittelberger remarked, "During the passage

there doth arise in the vessels an awful misery, stink, smoke,

horror, vomiting, sea-sickness of all kinds, fever, purgings,

headaches, sweats, constipations of the bowels, sores, scurvy,

cancers, thrush and the like, which do wholly arise from

the stale and strongly-salted food and meat, and from the

exceeding badness and nastiness of the water, from which

many do wretchedly decline and perish." Mittelberger,

like many others, traveled on a cargo ship haphazardly altered

for travelers through the construction of a makeshift deck

built between the upper deck and the hold. Since it would

be collapsed after disembarkment to make cargo room for the

return voyage, the deck was loosely built, primitive, and

uncomfortable. The ship’s hatches provided the sole

ventilation and were clamped shut when the weather turned

foul. Latrines were scarce and the middle deck was entirely

open, affording little privacy for women, who sometimes found

themselves molested by the ship’s crew. By the mid-eighteenth

century, shipping tactics and conditions, particularly on

vessels owned by an especially nefarious English company

called Stedmans, had refined themselves nearly to the point

of rivaling the Atlantic slave trade in overall cruelty and

dehumanization. Between 1750 and 1755, two thousand passenger

corpses were cast into the ocean.

Onboard, travelers were expected to provide their own meals

and, having little or no prior knowledge of sea travel, they

usually misjudged their provisions; if their supplies gave

out, they had to buy food from the captain, for which they

were charged exorbitantly – a calculated measure to

bury them deeper in debt. Those who brought with them chests

full of dried meats and fruits, brandy, and medicine often

were forced to leave them behind or store them on other ships,

which again placed the traveler at the mercy of the ship’s

commanding officer. If a passenger died during the passage,

family members were charged the individual’s fee, a

particularly tough blow if the sole survivors were women

and children. If a child’s guardians both died, the

minor would become the property of the captain who would

then sell the child as a means of exacting payment for the

parents’ fare. Plummeting into debt meant having your

family become servants in the New World. The going price

for a man was ten pounds for three years of servitude; some

were bought for up to seven years, and children were owned

until the age of twenty-one. In return for this specialized

variety of slavery, the owner would pay off whatever debts

the traveler owed the captain – the process was called

the "redemptioner system." The eighteenth-century

German immigrant arriving in Philadelphia harbor would have

been allowed to disembark only if his sea passage was paid

and he had no outstanding debts. Those who owed money waited

to be sold off, the healthier going first and the sick and

the weak sometimes dying onboard, too useless for purchase.

Being bought by a master carried with it no guarantees of

fair treatment or extended care. People could be swapped

or sold if they did not fit the owner’s plans. As one

period advertisement read, "For sale, the time of a

German bound girl. She is a strong, fresh and healthy person,

not more than twenty-five years old, came into the country

last autumn and is sold for no fault, but because she does

not suit the service she is in. She is acquainted with all

kinds of farm work, would probably be good in a tavern. She

has still five years to serve." As horrific as this

process might sound to twenty-first century readers, the

sum and utility of a human being set in the bargain value

context of a newspaper’s classifieds section, we must

do our best to keep it situated in the context of the time,

during which such prospects did not seem completely unpleasant

alternatives to the mauling periodic violence and ongoing

deprivation of early eighteenth century life in the Palatinate

or Bavaria. Furthermore, as with all slaveholders, there

were good masters and bad ones, and the degree of youth,

strength, and potential knowledge of a trade affected the

manner in which people were treated, the adept learners and

hard workers quickly becoming indispensable to their masters,

the weak and the slow loathsome burdens. Difficult for the

modern thinker to grasp, the system was devoid not only of

civil rights, but of any rights at all; and though it is

said to have been increasingly "humanized," the

practice was not abolished altogether until the 1820s.

Always departing – not unlike my ancestors, though

my conditions remain decidedly more favorable – I feel

myself nonetheless ever present in the place through which

I am passing – the living domain that is the visceral

continuum of the traveler, experienced and remembered. It

is fanciful in any event and perhaps ultimately irresponsible

to wish to disappear entirely, dissolve ourselves utterly,

from the inevitable conflicts that afflict the human who

lives among other humans – the cruelties we collectively

visit upon animals, each other, and the world itself – as

well as the more harmless manifestations and vestiges: abstract

cultural clashes, the packed professional wrestling arenas

and football stadiums – those grand American coliseums,

the coarse weekend battletowns of our time.

Outside forces propelling us into scenarios and identities

we could never have imagined, ours remain lives that drift

indefinitely so long as they are. And sorrowful is the soul

swept on a strong current, rudderless, until at last it finds

that stagnant pool, where still waters offer up the morbid

image of what it truly is – this dying thing it never

intended to be. Yet so long as there is intention there is

hope, for intention is a window that opens upon the heart.

Being can never be dead so long as we mean to become something.

And we can do worse than mean well.

January 2007

From guest contributor Casey Clabough

|