In my hungry fatigue, and shopping for images, I went into the

neon fruit supermarket.

-Allen Ginsberg," A Supermarket in California,"

1955

Introduction

Welcome to H.E.B., one of Texas’ largest grocery chains

with over 300 stores throughout the state. Inside, we find the

visual trappings that are typical of the large-scale supermarket

industry: linoleum tiles, stadium ceilings, florescent lighting,

and clearly gridded aisles. At selected H.E.B. stores, however,

a new section called Nature’s Harvest has been created to

serve the needs of a different brand of shopper, a group I am

calling the “thoughtful class.” This class can be

defined by disproportionate access to education, wealth, and transportation.

They shop with moral and intellectual intention, putting their

money where their mouths are. The section of H.E.B that caters

to this type of consumer specializes in organic, “healthy

foods” and is visually separate from the managed aesthetics

(or lack thereof) governing the rest of the store; track lighting,

lowered ceilings, angled aisles, and hardwood floors greet H.E.B.’s

Nature’s Harvest shoppers. An exotic oasis among the clamor

of shopping carts, the natural food section provides the artificial

comfort of a local co-operative in the jowls of corporate consumption.

For the thoughtful class, shopping is a personal experience in

the moral landscape of organics. Imagined cultural ideals of eating

healthily while supporting cultural and biological diversity are

encouraged within the constructed supermarket space and are reinforced

through the commodification of historical and indigenous images.

In this paper, I will explore the ways exoticized histories and

representations of otherness are deployed on organic cereal boxes

to frame the healthy breakfast as an ancient ritual. I will also

analyze the ways ethnicities are constructed and commodified on

organic brand cereals and the aesthetic construction of opposing

histories through nostalgia for an idealized agrarian past.

The Setting

Cereal is a uniquely American food. A walk down the cereal aisle

is an experience in American vision. Unlike other sections of

the store where items vary by size or shape, the cereal aisle

has the same-styled box pressed one against the other. These standardized

8x11 boxes resemble hypercolor stacks of television sets, each

a visual talking-head flashing sports stars, cartoons, or slim

models. We find a similar, though differently hued, experience

in the Nature’s Harvest supermarket section. Here, the organic

cereal aisle is more like a terraced garden overgrown with images

of parrots and colorful, “exotic” people. It is an

interwoven expression of subaltern and popular culture. The iconic

predominance of the “natural” world speaks to this

association of all things green to all things good, and the multi-chromatic

array of faces reinforces diversity as the path to a balanced

meal. As such, the very nature of the cereal box is performative,

intended to attract the attention of the consumer through culturally

recognizable and emotionally resonant images.

The cereal box occupies a space, a vision, and a location all

at once. After we have purchased the cereal, we are expected to

sit down and read the box as part of the morning ritual. In an

oddly-sustained, postmodern version of a Norman Rockwell portrait,

the timeless place of the American cereal box, organic or not,

is atop a breakfast table, next to an open newspaper and a half-gallon

of wholesome milk. Indigenous images on organic cereal boxes are

used as cultural windows that bring the meals of the “natives”

into our home, and essentialize breakfasts across time and place.

To more closely regard the commercial reification of the “natural,”

I will consider one particular brand of organic cereal found in

all H.E.B. Nature’s Harvest health food sections: Nature’s

Path’s Mesa Sunrise.

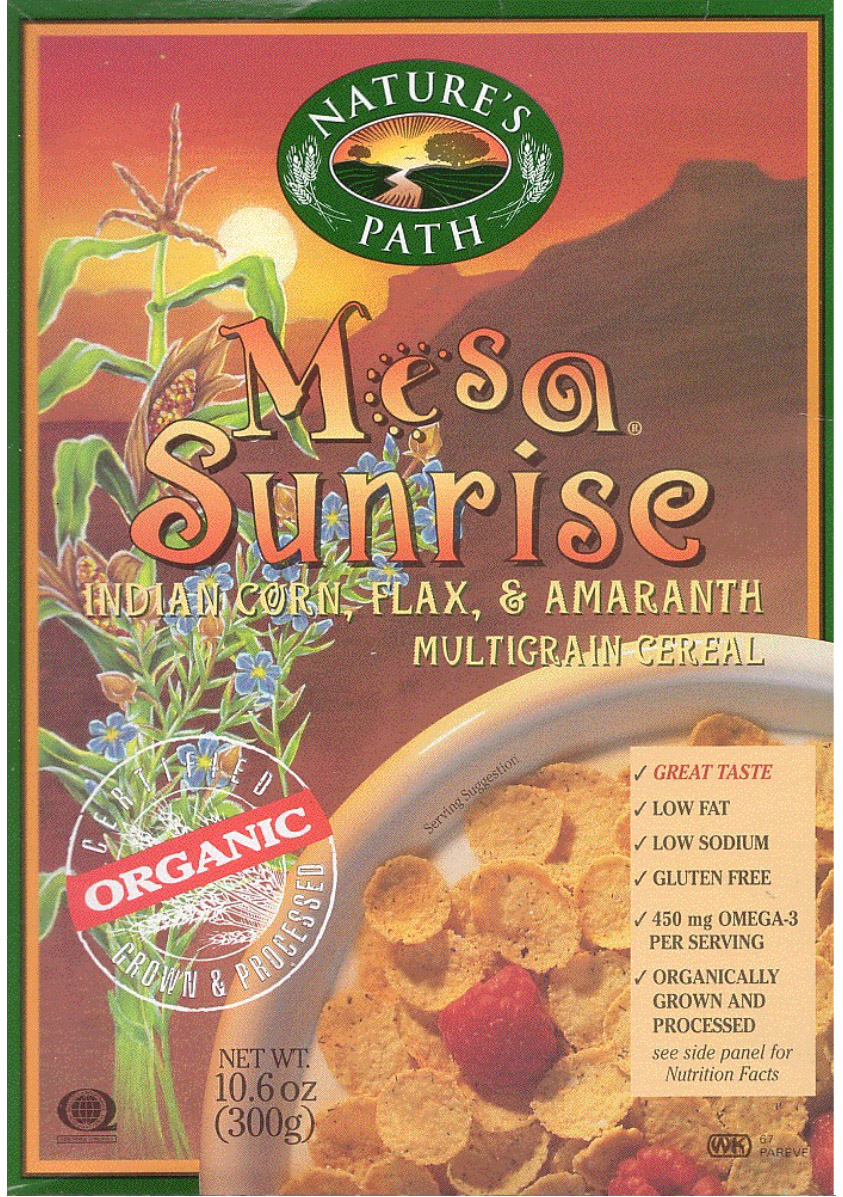

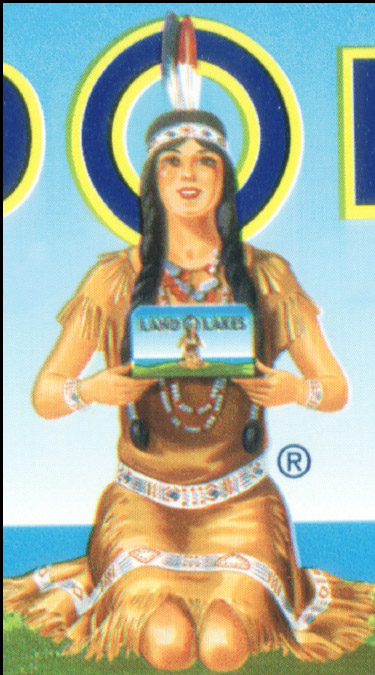

Figure 1

Figure 1

The Box

The box of Mesa Sunrise cereal is a rich desert oasis within our

organic aisle garden. Orange skies and golden buttes halo a bounty

of gathered grains on the front of the box, over which curls the

cereal brand name in a font suggestive of petroglyphs. The carefully

crafted title, Mesa Sunrise, conjures up a mythical, Southwestern

landscape while subtly referencing the actual home of the Hopi

Indians: Northern Arizona’s Three Mesas. The brand name

is quixotic, evocative, and highly poetic (see figure 1). In Sunrise,

we are reminded how natural and timeless the morning ritual of

breakfast is; the high, flat-top Mesas are the world’s own

breakfast table. Sunrise also recalls a pre-industrial epoch when

the passing of time was not marked by the clock, but by the natural

rising and falling of the sun. On the back of the box, we find

a bricolage of historicized images, effluent quotes, and scientific

jabber, peppered along the margins with peeling corn and flowering

plants. The overall presentation of the box is intended to tell

the cultural and environmental story surrounding the cereal we

are about to consume. By displaying a collection of disparate

images in this way, a self-reflexive framework of meaning is crafted

which totals more than the sum of its parts. These images are

strategic; each historic reference builds on the next to construct

an overall product narrative: history is available for consumption.

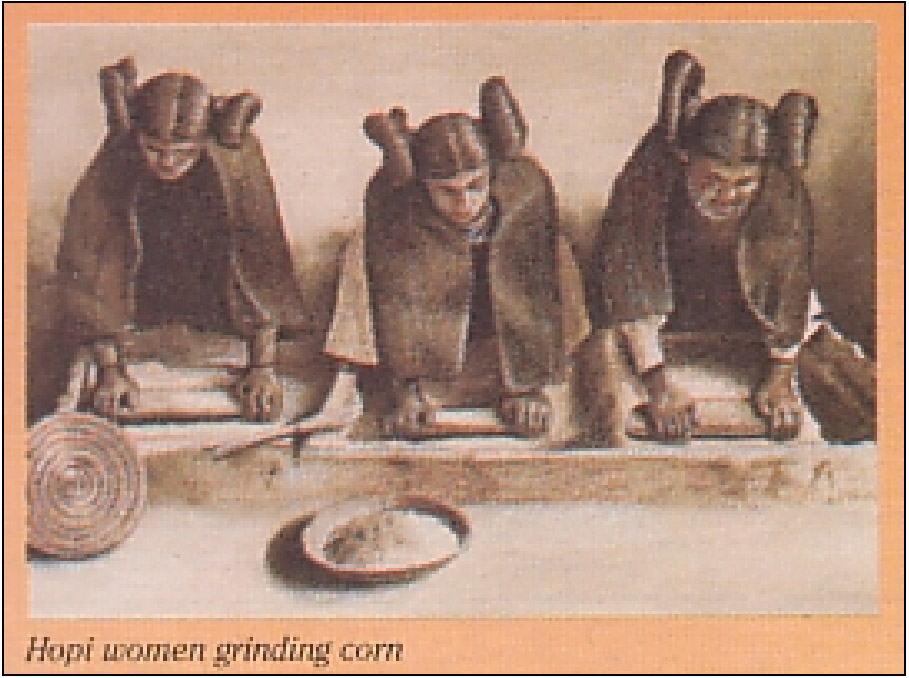

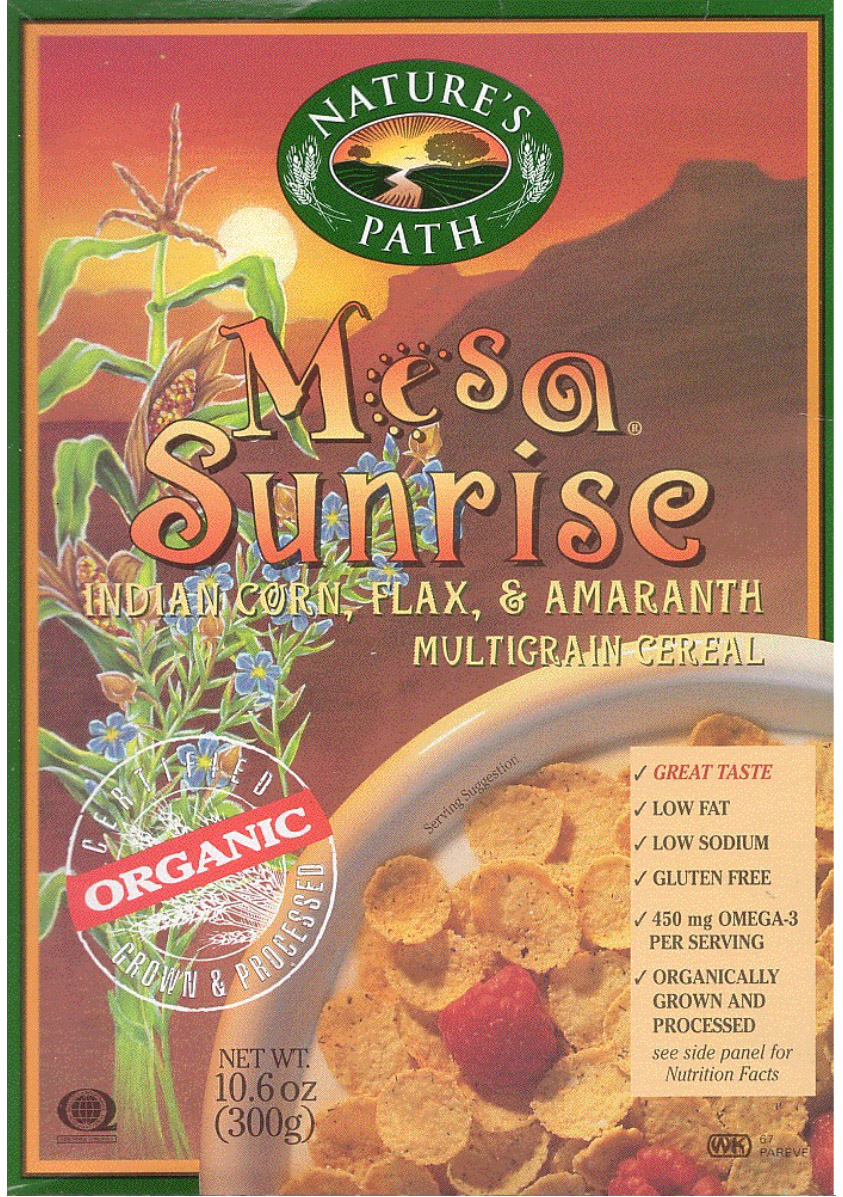

For example, an image of three women kneeling over their stone

metates is captioned with the text, “Hopi women grinding

corn” (see figure 2).

Figure 2

Figure 2

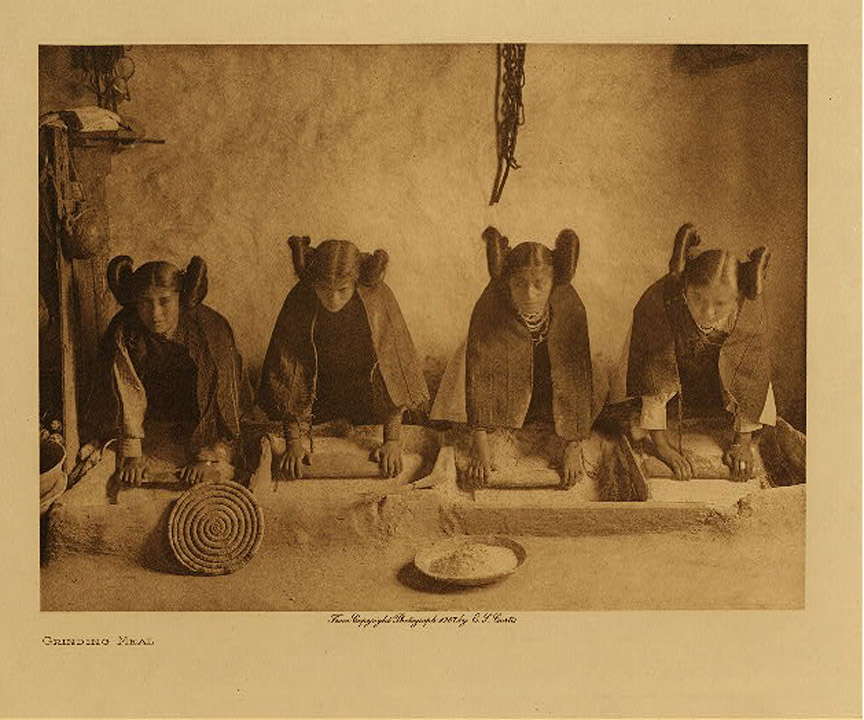

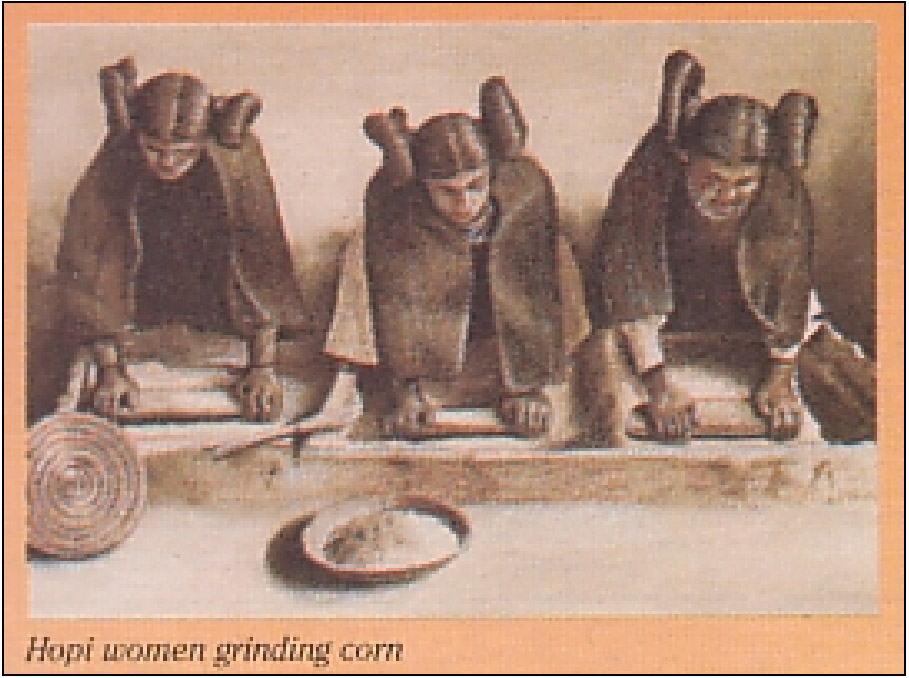

Figure 3

Figure 3

The image is visually intimate and sepia-toned, as though we

were witnessing a private moment at home. Yet, with some research,

we find that the Hopi image is a photoshopped version of an early

photograph taken by renowned photographer Edward Curtis in 1907,

merely twenty-five years after the Hopi reservation was created

(see figure 3). At that time, ethnographers, missionaries, and

government agents were all climbing the mesas, vying for glimpses

into the Hopi world. Alone, Curtis’ presence as a camera-laden

White man would likely render the gentle domestic scene contrived.

Mesa Sunrise cereal locates itself in the landscape and constructs

a stereotypical Hopi ethnicity around a “real” (though

itself constructed and highly problematic) historical image of

grinding maidens: no other information or details are given beside

the caption. The dress, hairstyles, and posture of these women

are not contemporary, and would likely only be seen in a ceremonial

or performative setting today. Yet, without historic information

or contextualization, we are made to believe that these three

Hopi women are still grinding corn in the recesses of our mass-producing

consumer present, just as Nature’s Path wants us to believe

that we are reading the cereal box from our own Norman Rockwell

breakfast table.

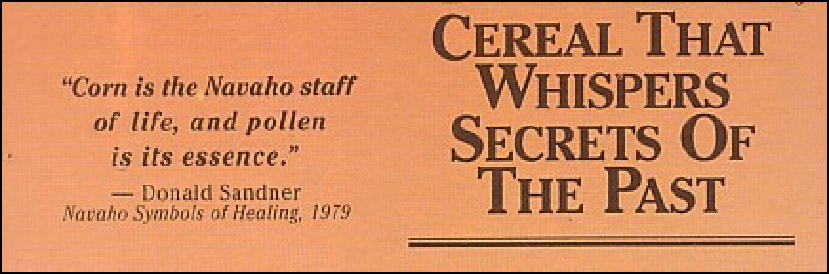

Native Americans are not static cultural beings as portrayed on

Mesa Sunrise; they are American consumers in their own right.

Over-simplified images of “timeless natives” are used

to represent a moment in time when humans had a more humble relation

to nature. Disparate tribes are grouped together to further show,

as the box says, “the pivotal position that corn has held

in the cultural lives of indigenous peoples.” Sitting just

atop the industrious Hopi image is a quote regarding the Navajo,

“Corn is the Navaho staff of life, and pollen is its essence.”

Just below, we find a brief Zuni coming-of-age anecdote: “The

Zuni people of the American Southwest measured time through kernels

of corn. A ‘generation of corn’ would be counted from

when a boy received his first planting seed to the time he gave

the seed to his own child to plant.” These quotes are double

constructions in that they offer no Native voices; only the words

of the “expert” are decontextualized and used as testimony.

The complexity of Zuni and Navajo cultures are reduced to single,

pithy narratives constructed around cereal. While these sound

bites may carry residues of historic validity, their uni-dimensionality

steals from them any real chance for meaning. Native Americans

represented on this box of cereal are fixed as media icons through

the commodification of their tribal identity or through the market

potential of their supposed traditions.

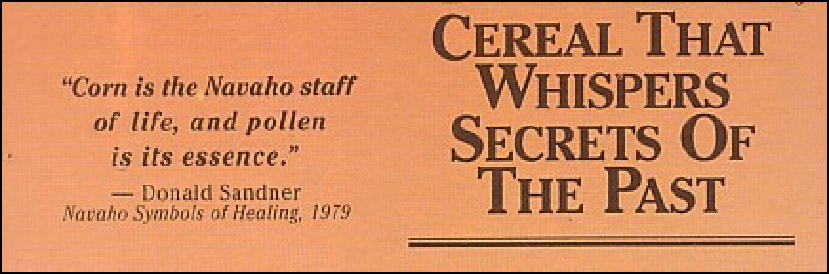

Figure 4

Figure 4

The back of the cereal box offers the central message: “Mesa

Sunrise - Cereal That Whispers Secrets of the Past” (see

figure 4). The “secrets” of indigenous pasts are just

that—whispers, the lifeblood of oral tradition to be counterposed

to written history. As such, these whispers carry traditions that

are transferred from one group to the next, as seen in the story

of the Zuni boy and his father who pass time and wisdom through

their heirlooms of corn. Mesa Sunrise implies that without the

textual “knowledge” of “real” (i.e. written)

history, fact is reduced to myth and history reduced to ethnohistory.

Moreover, while these possessors of traditional knowledge may

hold valuable information, their experience is neither associated

with thought, nor individualism. Rather, it is assumed that oral

knowledge should pass unmarred through the transmitters of human

memory; critical thinking and autonomy must be subverted in the

process.

For the Mesa Sunrise consumer, the “past” is neatly

divided into the left- and right-hand sides of the cereal box.

To oppose the North American Indians’ use of corn as a spiritual

and calendric sacrament (on the left-hand side), the manufacturers

place (on the right) the great European “cultivation”

of cereal for early scientific and medicinal purposes. Through

this visually articulated division, we see two contrasting histories

that serve to validate and contradict one another.

The Message

In “Disjuncture and Difference in the Global Cultural Economy,”

Arjun Appadurai makes the following statement about a situation

similar to the one we find on the Mesa Sunrise cereal box, “Here

we have nostalgia without memory. The paradox of course has its

explanations, and they are historical: unpacked, they lay bare

the story of American missionizing and political rape” (3).

A critical reading of the text-and-image collage on our box finds

a potential naturalization and trivialization of the backbreaking

labor of those involved in actual cereal production and those

who ground corn on their hands and knees. Moreover, a subtle gendering

occurred during the photo alteration of the original 1907 Hopi

photograph. Unlike the Edward Curtis 1907 photograph, none of

the Hopi women portrayed on the box of Mesa Sunrise are making

eye contact with the viewer. Instead, they are all looking down,

suggesting the passivity of indigenous, female labor. The presentation

of passive Native women on their hands and knees asserts a contemporary

“we are better off” notion that is reaffirmed through

iconographic analogies between breakfast in “our world”

and food production in “their world.” Behind the seemingly

innocuous representation lies the mechanics of power that allow

one group to own another through manipulation of image and identity.

Indians captured on the cereal box have been appropriated by capitalist

production, a fact which must not be overlooked.

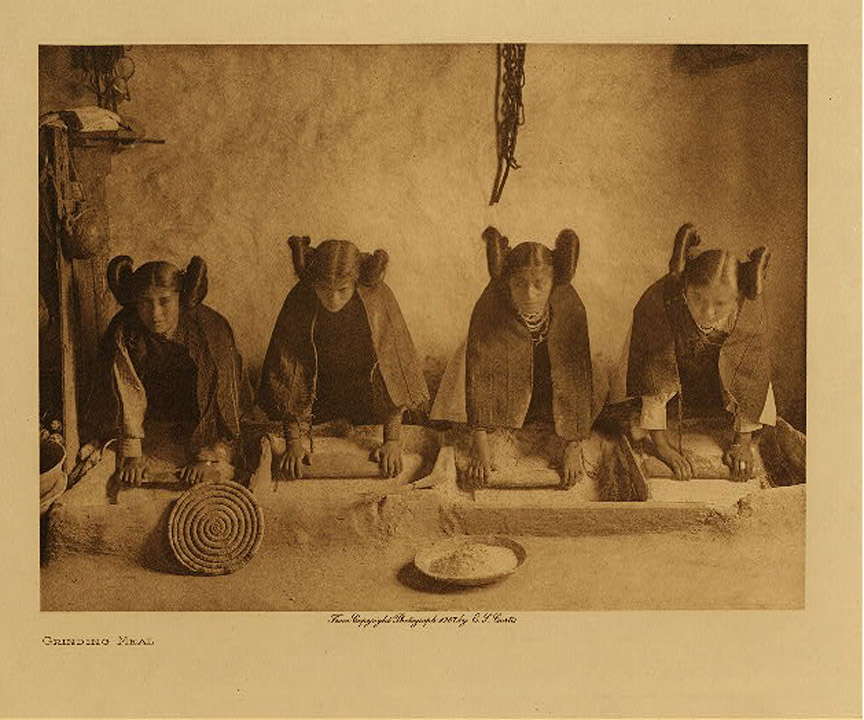

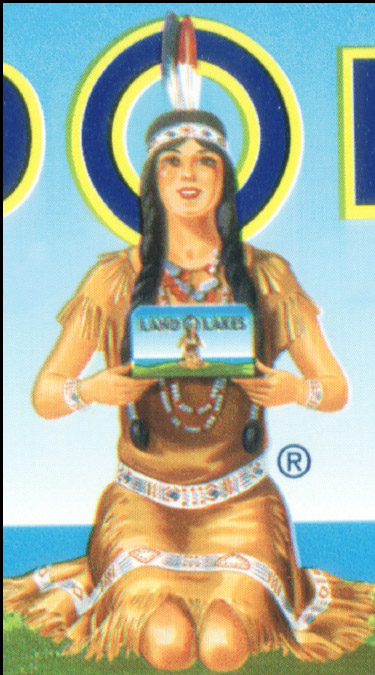

The act of naming others is an act of control through representation,

as it has been observed by academics and consumers alike (see

Berkhofer and Bordewich). Native Americans have long suffered

the brunt of such representation. In many places, antiquated cigar-Indians

still flank drug stores and cigar shop entryways. Painted or feathered

Braves and Redskins still make their battlecries on the fields

of sports teams. And the Land-o-Lakes butter Indian sits “Indian

Style” atop her creamed throne, adorned with a single feather

and two browned knees emerging from under her buckskin skirt (see

figure 5). Aside from their lingering remnants, the classic twentieth-century

images of the American Indian are now largely understood as racist

caricatures. As noted by scholars and activists (see Alexie, Churchill,

Dilworth, and LaDuke), these representations are far from vanquished;

rather, they are being re-marketed to a contemporary audience

under a different premise. There has been a significant shift

from the stoic Chief and sexualized squaw, to the deeply spiritual

and environmentally conscious Native American. Now, a different

ideal—the natural—is being sold through a modified

Native American image.

Figure 5

Figure 5

Because the vast majority of American families were once immigrants

to this country, Americans have taken the liberty to “rewrite

history in a self-justifying manner by redefining Native Americans

as part of their own past” (Huhndorf 5). Contemporary American

life is often held in oppositional tension to an imagined pre-industrial

Native American world. This is not wholly a new phenomenon. As

Leah Dilworth remarks in her seminal work, Imagining Indians

of the Southwest, anthropologists were using ethnography

as a tool for critically assessing popular American culture as

early as the 1920’s (192). Not long after his linguistic

work with the Hopi, Edward Sapir published an article in the

Journal of American Sociology that polarized the Southwest

United States into “genuine” and “spurious”

cultures, the former representing an ideal pre-industrial state,

and the latter encompassing the fettered modern world. Much as

might be seen today, “spurious” American culture was

encouraged to look to indigenous culture for a cure to the spiritual,

cultural, and physical woes caused by over-industrialization.

Sapir writes, “Genuine culture is inherently harmonious,

balanced and self-satisfactory” (314). Nature’s Path

uses the Hopi image of industrious small-scale corn production

to invoke the fantasy that Mesa Sunrise is hand-made rather than

mass-produced. It is thus more “natural”; if you eat

it, you will feel harmonious and balanced.

This harmonious and balancing Indian replaces its racialized predecessor

with a softer, more “authentic” and “natural”

representation. Today’s “Indian” is as much

a creation as the cigar Indian, crafted hodgepodge from staged

photographs, stolen stories, and fabricated rituals. Thus, two

contradictory, but constantly intertwined, modes of imagining

indigenous peoples occur. The complex and shifting valences of

respect and disregard converge in the public imagery today. All

such representations, whether flattering or disparaging, are fundamentally

dehumanizing.

While Nature’s Path cereal would not admit to representing

Indians in such iconic forms, we see from the above discussion

that “their” Native Americans are stereotypes nonetheless.

What is unique about the marketing scheme employed on Mesa Sunrise

is the very intentional tribalization of its indigenous representatives.

Through early ethnography and photography, individual tribal identities

can be forged into a display of cultural diversity and historical

accuracy. All the while, the identities of individual indigenous

actors are blurred behind generalities of tribal affiliation.

The Hopi women grinding corn are neither listed by name nor differentiated

in dress. Their consumer worth is not in the product of their

work but in the labor of their kind: “authentic, primitive,

and undifferentiated.” Superficially, the cereal box attempts

to dismantle this “homogenized Indian” by tribally

differentiating between Native cultures in the Southwest. Likely

resulting from their historic relation to the early railroad tourism

industry, as well as their own successes at self-promotion, the

Zuni, Hopi, and Navajo tribes have become culturally recognizable

entities. I believe that the deliberate reference to these tribes

serves a separate function beyond the replacement of an older

generation of essentialized Indian forms.

Nature’s Path does not use just any tribal identity to (re)present

its cereal. The Hopi and Zuni have long been recognized as popular

tourist attractions in the Southwest. They are culturally marked

and seen as historical remnants of earlier times. Grand Canyon

guidebooks abound with one-dimensional descriptions of their cultures

and directions to the nearest pueblo gift shops selling their

“traditional” crafts. The guidebook put out by the

Arizona Association of Bed and Breakfast Inns and available electronically

for online perusal reads: “The Hopi village of Oraibi is

one of the two oldest continuously inhabited communities in the

United States. While it is possible, with permission, to wander

around Oraibi, you will likely learn more about Hopi culture by

opting for one of the guided tours of Walpi village, which sits

atop First Mesa. Throughout the Hopi mesas you will find numerous

crafts shops and artists' studios where you can shop for kachinas,

silver jewelry, and pottery. From the Hopi mesas, head south to

I-40 and back to Flagstaff.” The Bed and Breakfast Association,

an exclusive echelon of the hotel industry, has marketed itself

around a patron type who appreciates exotic life, “off the

beaten path,” with the comforts of home. Just as the language

of the B&B guidebook appeals to a particular type of traveler,

so too the back of the organic cereal box appeals to a selective

group of consumers, perhaps the groups even overlap. These strategic

marketing representations reflect the way consumers imagine their

own, as well as other, cultural identities and make their choices.

The language of the cereal box relies heavily on history-rich

words such as “over the millennia,” “ancestors,”

and “generations,” to develop an overall feeling of

history. Yet, as mentioned above, we are presented with two distinctly

different historic timelines. The history of European civilization

where agricultural decrees (“800 AD Charlemagne passed laws

requiring people to use flax”) and medicinal knowledge (“Hippocrates

used flax to relieve digestive problems”) are encrypted

in text (“Evidence from the writings of Hippocrates show”)

and are held against the traditional past of North America (presented

in pictures and stories) where wizened ancestors passed on ancient

farming knowledge through whispered secrets and ritual. Although

it has been archaeologically established that natives cultivated

both flax and amaranth in what is now the Southeastern United

States well into the thirteenth-century, Mesa Sunrise only shows

Native Americans as raising “colorful maize.” The

Old World stories of flax and amaranth include dates (5000 BC,

650 BC, 800 AD) and recognizable names (Charlemagne, Hippocrates)

in order to show the pedigree of an identifiable history as opposed

to a New World pre-history full of undocumented ancient traditions.

These disparate timelines are intended to weave through each other,

imbuing Mesa Sunrise cereal with a whole world of historic and

grainy diversity sanctioned by “natural” tradition

and historic veracity. All the while, the methods of analysis

are essentially Hegelian; by employing the logic of dichotomy,

European reason and science are deified.

The box reads, “Every spoonful of Mesa Sunrise connects

you through the centuries to knowledge and traditions around the

benefits of ancient grains that contemporary science is now beginning

to support.” We read that contemporary science is finally

catching up to the wisdom gained through history. A scientific

lexicon (soluble fiber, lignans, and omega-3 fatty acids found

in flax) further legitimates a “traditional” past

and brings this past into the present. Scientific and historical

language and images are used in emotionally evocative ways. Cereal

grains are bound up with symbolic meaning, and this meaning is

codified in traditional food diets, historical names, dates, and

places. Compared to the ancient peoples’ world and their

ties to nature, the present, not unlike Sapir’s “spurious

culture,” is seen as a world of loss. Consumers now have

the opportunity to reap both the benefits of contemporary scientific

knowledge and colorful ancient ritual.

The organic movement is ripe with nostalgia for the “simpler”

era when the process of eating was itself a ritual act. The images

Nature’s Path presents show the Native American past as

one that is bound up with ritualistic agrarian practices. These

images actively assert a valid and natural connection between

food and wisdom. Moreover, the cereal box language presents the

past in such a way that suggests we too can gain wisdom through

eating the same ancient grains. Just as we are intended to digest

the guidebook histories of the Native Americans through images

and quotes, our bodies are granted effortless access to “centuries

of knowledge” through breakfast cereal. The cereal goes

beyond simply asserting that healthy food will make us wise. By

presenting the powerful history of ritual food practices, consumers

are enticed to bring ritual into their own lives through the consumption

of organic foods. The pre-existing American cultural practice

of eating breakfast (à la Norman Rockwell) can be imbued

with meaning and enshrined in ritual when the element of moral

intention is added. The knowledges and “by hand” labor

of the Native are rich with tribal significance but empty of meaningful

autonomous action. Today’s shopper can bring individuality

to the past by translating the ancient experience of eating naturally

into a contemporary organic lifestyle. A ritual of healthy eating

(including, of course, corn and flax found in Mesa Sunrise), will

enrich the body and the mind, creating a wiser person, which in

today’s consumer society is equivalent to a thoughtful class

of shopper. Mesa Sunrise relies on a narrative of nostalgia for

the timeless yet vanquishing primitive that is validated by a

scientific lexicon and a constructed Old World history.

Conclusion

Mesa Sunrise is a cornflake cereal boasting ingredients of organically

grown and processed flax, amaranth, and “Indian corn.”

The cereal box itself is like a miniature Levi-Straussean museum

assembled from the stolen bodies and cultural sacra of the past,

and reworked into a modern narrative. The images that collide

and are juxtaposed on the box belong to two different visions

of the past, one traditional and the other historical. Much like

H.E.B.’s constructed “Nature’s Harvest”

environment, Mesa Sunrise cereal constructs a visual narrative

around fabricated cultural identities, thereby creating a product—and

a consumer—just exotic enough to be healthy.

Works Cited

Alexie, Sherman. Old Shirts & New Skins, Native American

Series; No. 9. Los Angeles: U of California P, 1993.

Appadurai, Arjun. "Disjuncture and Difference in the Global

Cultural Economy." Public Culture 2.2 (1990): 1-24.

Arizona Association of Bed and Breakfast Inns. 2004. <http://www.arizona-bed-breakfast.com/travelplanner-5.html>.

Berkhofer, Robert F. The White Man's Indian: Images of the

American Indian, from Columbus to the Present. New York:

Vintage Books, 1979.

Bordewich, Fergus M. Killing the White Man's Indian: Reinventing

of Native Americans at the End of the Twentieth Century.

New York: Doubleday, 1996.

Churchill, Ward. From a Native Son: Selected Essays in Indigenism,

1985-1995. Boston, Mass.: South End Press, 1996.

Dilworth, Leah. Imagining Indians in the Southwest: Persistent

Visions of a Primitive Past. Washington: Smithsonian Institution

Press, 1996.

Ginsberg, Allen. Collected Poems, 1947-1980. New York:

Harper & Row, 1984.

Huhndorf, Shari M. Going Native: Indians in the American Cultural

Imagination. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 2001.

LaDuke, Winona. The Winona Laduke Reader: A Collection of

Essential Writings. Stillwater, MN: Voyageur Press, 2002.

Sapir, Edward. "Culture, Genuine and Spurious." American

Journal of Sociology 29 (1949): 308-331.

Figure 1

Figure 1 Figure 2

Figure 2 Figure 3

Figure 3 Figure 4

Figure 4 Figure 5

Figure 5