Introduction

Years ago authors Barnet and Cavanagh portended: “The new world economy rests largely on global bazaars” (15). Today, India is a major economic promontory in the voyage of western filmic expansion into the East. As a “movie-mad country” (Chopra 18), with its own yearly production output of “over a thousand movies in Mumbai alone” (Beaufoy, Boyle and Feld 142) - numerically translated as “3 billion movie tickets per annum” (Lakshmi 8) - Bollywood unlike Hollywood boasts a 13% increase in movie ticket sales since 2007 (Chopra 18). Film scholars have for years tracked the so-called “economic moribundity” (Cowen 73) of European cinema. In contrast, “India’s film industry, now at $2.2 billion, is estimated to grow to 3.3 billion by 2013” (Lakshmi 8).

Cowen claims that the "English language, combined with America’s role as a world leader, has strengthened Hollywood exports” (75). In India, the linguistic “legacy of English” (Bhatia and Baumgardner 384) makes the economic venture eastward into “the prized Indian market” (Tyrrell 260) a viable option as increasing economic research confirms that “the global market has generated more dependable returns than the local market” (Dissanayake 405). Esteemed linguist, David Crystal calls India “a linguistic paradise” (173) with “a special place in the record books” as a country with “the largest English-speaking population in the world” (173) at “350 million speakers” (173). This figure is “far more than the combined English-speaking populations of Britain and the USA” (173). Two decades ago in a comprehensive analysis of Hollywood versus Bollywood, Tyrrell claimed that “Hollywood has not defined what makes a film work in India” (260). Twenty years later, Slumdog Millionaire has demonstrated that when it comes to “the battle of the dream factories” (Tyrrell 260), “Hollywood’s colonization of Bollywood” (Tyrrell 272) can indeed be achieved via a twin strategy of linguistic and cultural syncretism.

The filmic genius of Slumdog Millionaire lies in the meticulous manner in which the hybridity of language and lore of both West and East have been glocalized to suit “the viewing tastes and linguistic preferences” (Bhatia and Baumgardner 380) of cross-continental audiences. Film critics are unanimous in their praise: “Slumdog Millionaire is the film world’s first globalized masterpiece” (Morgenstern 1) raves the economically savvy Wall Street Journal. How did Slumdog Millionaire do it? The answer lies in the innovative use of verbal and visual English as cinematic strategy - as “an aural and visual spectacle” (Garwood 174) within the “diegetic space of film” (Garwood 179). Visual English consistently dominates screen-space in Slumdog. The film’s economic and aesthetic genius rests on the nuanced, multiplex manner in which visual English “functions in the ever-evolving techno-aesthetic space of cinema” (Dissanayake 406) - as a filmic device which reflects at the very same time as it sustains a place for global English evanescence. The effective incorporation of tokenized Hindi in the movie as a vehicle for highlighting verbal and visual English is accomplished in and through a plethora of potent filmic strategies including but not limited to: spotlighting, achieved via filmic prominence given to visual English; synchronization, accomplished via a savvy glocalization of tokenized local linguistic content in the service of linguistically dominant global interests; spectacularization, realized via an intelligent use of selective adaptation strategies which simultaneously translate and transliterate "Indian figurehead" novel-writing and music-making potential into globally appealing cultural products, and finally, syncretization - filmmaking strategies which “utilize an economic and cultural dynamic that combines both commercialism and creativity” (Cowen 101) - four cultural production strategies which use the local to sell the global. All four strategies are detailed below.

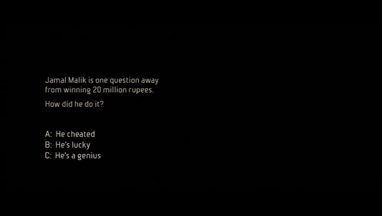

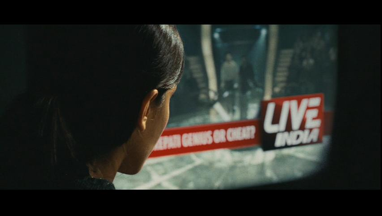

Figure 1

Spotlighting

The A, B, C and D of Visual Englishing: "It Is Written"

Visual English is a central actor in this global blockbuster. Set against a mesmerizing soundtrack of a ticking clock, the movie unfurls with spotlighted visual English in the form of the double-punned phrase: "It is written." This phrase forms two separate stills at the beginning and the end of the movie. This visually rendered phrase which “bookends” (Garwood 180) the filmic narrative is a powerful exemplar of glocalization (see Figures 1-3).

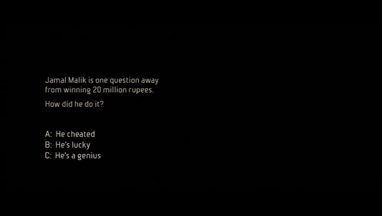

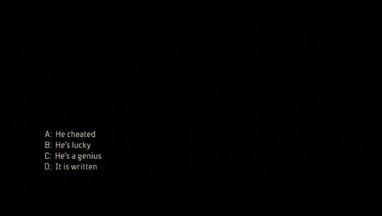

Figure 2

Visual English is used to cinematically index locally transliterated beliefs in destiny, in kismet - in what is "written." The complementarities of a black cinema screen to spotlight the simplicity of white visual English in the form of a potent and dynamic filmic interrogative which is “spelled out on the screen” (Sragow 1) serves as a key narrative tool at the very same time as this cinematic strategy functions as a prompt to acquire English. Only a reader of English can venture a response, or even follow the foreshadowed thesis since: "It is written" [pun intended]. In this film, visual English is a filmic tool used to “immediately pull you into a matrix of volatility and suspense” (Sragow 1) or what film critic Wax appropriately calls “a frenetic 120-minute tale” (1).

Figure 3

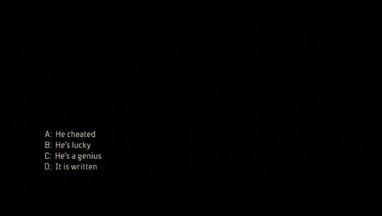

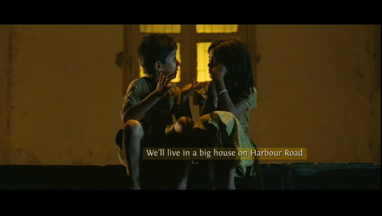

Visual English also gets the last word in the film. There is a repeat of the kismet-driven cinematic thesis provided against a universal metaphor of chaste love verbalized as: "This is our destiny" - a transliteration of the Hindi phrase - likha hai - it is written - a kiss on the lips which, while "taboo" on Indian silver screens, is a filmic risk also already attempted by newer “trendier” Bollywood releases (Garwood 180) (see Figure 1).

Floating English Subtitles: Creating Linguistic Dynamicity

Perhaps one of the most potent strategies Director Danny Boyle employs to forefront the visual dynamicity of English is to utilize subtitles as “stylish and splashy and original” (Beckman 5) linguistic devices. After all, this film earned three Academy Awards in the areas of directing, editing, and cinematography. The act of prompting an on-screen "reading" of English as a conscious decision on the part of the filmmakers is evident in an interview with Boyle who confesses that he wanted the subtitles “to be read like a comic book” (Beaufoy, Boyle, and Feld 141). The move from a static, bottom-screen, predictable placement of - “subtitles as plain white lines of text tethered to the bottom of the screen” (Beckman 5) to dynamic, floating subtitles unpredictably appearing in multifarious screen-positionings - visual English forefronted against a vivid backdrop of India - which “bounce around the screen in a rainbow of colors” (Beckman 5) - creates a powerful semiotic effect of linguistic saliency. English is volatile in this film. Audience members cannot fail to notice the vividly colored English slowly splashing across each scene. On the aesthetic appeal of this strategy, film critic Beckman comments, “In one scene set in an outhouse, green and amber-backed subtitles bring jewel tones to an otherwise brown-toned shot” (5) - testament that in this film “English is self-consciously established as a visually pleasurable object to the viewer” (Garwood 175) - a strategy also noted in recent “songless” (Garwood 175) Bollywood productions.

This powerful filmic device was a compromise Boyle came up with for studio executives when the initial script “written completely in English” (Beaufoy, Boyle and Feld 141) had to incorporate Hindi dialoguing in the first third of the movie because of the child actors’ linguistic barriers: “none of whom spoke English” (Jurgensen 6). Upon the advice of the Indian “co-pilot of Slumdog” (Jurgensen 6), director Boyle “assured the Hollywood executives that he hadn’t lost his mind” and “made them a promise: that the film would be even more exciting because of the subtitles” (Beckman 5) - code language reassurance for the film’s potential for “commercial success” (Cowen 79). We are also reminded that in “Hollywood, studios scrutinize projects intensely and refuse to finance projects” (Cowen 79) that promise poor economic returns. Boyle recounts the studio’s reaction: “And I remember the pause on the line. You could tell they thought I had gone upriver” (Beckman 5). He reiterates this in an interview with film critic Robert Feld:

So, Loveleen said, “Listen you should really do it in Hindi.” I, of course, thought, Oh my God what’s Warner Brothers going to say if I do that? So she adapted the dialogue and as soon as she did it, the kids suddenly came to life.... So, I did ring Warner Brothers and said, “We’re going to do the first third in Hindi with English subtitles.” They just thought I was losing my mind... (Beaufoy, Boyle and Feld 141)

Figure 4

In Boyle’s own words: “We tried to make the subtitles vibrant and different…to pop around the screen...so that when you look at the screen it is easy to take in” (Beaufoy, Boyle, and Feld 141). The promise seems to have been fulfilled. Critics were euphoric in their praise of what one cleverly called an “out of character role for subtitles” saying: “Rejoice - subtitles have been freed! They’re liberated” (Beckman 5) (see Figures 4 and 5).

Figure 5

For the halting English speaker, these subtitles take on an effective pedagogical look of highlighted text. One could potentially leave the theater having learned a few of these "highlighted" expressions. The subtitles in Slumdog Millionaire function in a dual capacity: visual English is “both naturalized (everyone in the film is comfortable with it) and elevated (it is prized as the language of education)” (Garwood 176). In this Hollywood production, English is further privileged as the language of access on both a literal and metaphorical level.

Objectifying English: Backgrounding and Foregrounding Devices

Perhaps the genius of the film lies in the use of English as a foregrounded cinematic object in itself. English is photographed as the central visual spectacle in several scenes in the film. Consequently, visual English occupies prime screen space. There are screen shots of stylized English - where visual English forms the sole filmic object in the cinemascape that meets the eye. Consider the following (see Figure 6) creative indexing of the English title of the film on a T-shirt. It is English, and not the wearer of the T-shirt (who is effectively dismembered) that meets the viewers’ eyes.

Figure 6

The spotlighting of English in Slumdog Millionaire was not accidental, but rather, a feat accomplished via conscious decision-making - in particular, via the use of specialized camera work. the technicalites of which are detailed by Boyle in his interview with Feld: “We used what we call a CannonCam, which was a Canon stills camera, which takes twelve frames a second...so it is a mixture of different technologies that we used in the film” (Beaufoy, Boyle and Feld 133, see Figure 7). Several of such trademark shots meet the eye in the Slumdog - even prompting film critic Morgenstern to appropriately comment that the film had “the zoominess of Google Earth” (1).

Figure 7

Verbal questions consistently see visual realization. The result: In this film we hear and see English continuously (see Figures 7 and 8).

Figure 8

The cinematic forefronting of the letter "B" relative to the "backgrounding" of Jamal serves as a superlative illustration of such spotlighting - visual forefronting at its prime (see Figure 9). In another instance, alphabetic English takes up all of the screen space (see Figure 10).

Figure 9

Figure 10

The use of English as a "backgrounded" cinematic strategy sees occurrence in the form of a seemingly innocuous and "peripheral" shot of a tattered sign urging viewers to “Speak English.” This verbal injunction is juxtaposed against a subliminal, and barely visible imperative: “learn” (yielding the phrase: Learn. “Speak English”) fairly prominent in the periscope of the cinematic topography (see Figure 11).

Figure 11

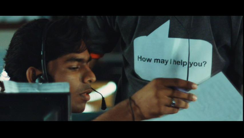

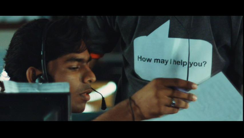

The spotlighting of visual English in almost every scene in the film from the files marked “M” in the police interrogation room to the repetitive English interrogative - “How may I help you?” - in the call-center scenes (see Figure 12) lends credence to the role of English in recent blockbuster releases from Bollywood where via a visual on-screen “projection of English” (Garwood 175) we find that “English gains some of the spectacular value more usually associated with the mise-en-scène and soundtrack of the song sequence” (Garwood 175).

Figure 12

Prominency is given to visual English in scene after scene, adding up to approximately twenty-four minutes of visual Englishing in Slumdog Millioniare. The consequence: “English words assume a physically desirable quality” (Garwood 175) in the accompanying unfolding action in the film.

Synchronization

Conflation Patterns: Glocalizing English

Like the cultural syncretism costuming the lead actress - jeans bedecked in the culturally "appropriate" head-scarf - even prompting one film critic to remark of Jamal’s love interest: “his beloved Litika is a multinational mingling of Juliet, Lara and the Vivien Leigh of Waterloo Bridge” (Morgenstern 1), the English of Slumdog Millionaire bears just the right whiff of Hindi spice (see Figure 13).

Figure 13

The constant flashback of Latika on the train platform that consumes the mind of Jamal and, inevitably, the audience showcases her against a train whizzing past in the hybridized background of English and Hindi (see Figures 14 and 15).

Figure 14

Figure 15

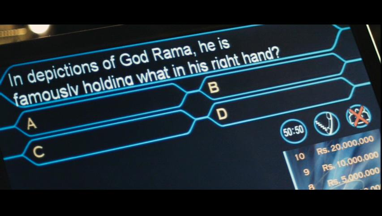

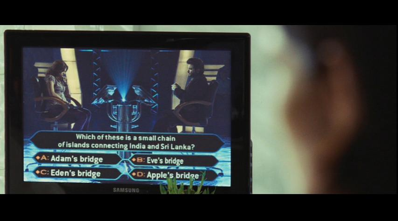

The glocalization of English occurs as game-show questions carefully conflating Indian schematic knowledge with selectively chosen global material-cultural awareness. Furthermore, this knowledge is invoked in and through prominently displayed on-screen visual English interrogatives which Jamal Malik and all viewing audiences attempt to answer. Also salient is the glocalization of visual content. Consequently, rather than focus on the theme of “erotic romance” (Cowen 93), so much a feature of Western films, Slumdog Millionaire emphasizes a love based on the Indian values of “obligation and loyalty” (Cowen 93) as well as modesty (Garwood 180). There is a marked absence of any form of nudity in the film - even in the brothel scene. Perhaps this is why the Slumdog team astutely hired an Indian co-director, Loveleen Tandan, who could “identify potential cultural gaffes” (Jurgensen 6). This synchronicity of language and culture is no more self-evident than in the encore thesis of the film - offered at the outset, and again, at the culmination of the film. The verbally inscribed role of kismet, the "D" of destiny gets the last word in the film: "It is written."

Also intriguing from a filmic standpoint is the intentional glocalization of filmic narrative features - the use of the Bollywood style of “melodramatic storytelling” for example (Beaufoy, Boyle and Feld 137). This influence is explained in detail by screenwriter Simon Beaufoy, winner of the Academy Award for best adapted screenplay for the Slumdog script:

As I stepped into a country where the monsoon rain is a weapon, the sun is blistering, and the tea sweet enough to strip the enamel from your teeth, the characteristics of the English writer - nuance, subtext, subtlety - all seemed inappropriate. For the first time in my career, I found myself experimenting with the grand, the operatic, the unashamedly melodramatic. (Beaufoy, Boyle and Feld v)

This “hybrid media convention” (Bhatia and Baumgardner 380) of synthesizing language and cultural script achieves two key goals: it provides a prominence of position to English while at the same time co-opting a partial, tokenized Hindi notation to “enhance an indigenous way of sending messages” (Bhatia and Baumgardner 381). The synthesis of Latinate and Devanagari scripts in the final movie credits (see Figures 16 and 17) is prime artistic evidence of the glocalization of language in the service of English. The result: These two languages seemingly exhibit “a shared discursive space” (Sinclair, Jacka and Cunningham 5) with a powerful semiotic purpose.

Figure 16

Figure 17

Slumdog Millionaire successfully utilizes English and Hindi for the twin goals of what Crystal calls “a balance between an outward looking language of empowerment and an inward-looking language of identity” (180) - English for the former and Hindi for the latter. Consider the Hindi "film-poster" manner in which actor credits are displayed, for example (see Figure 18).

Figure 18

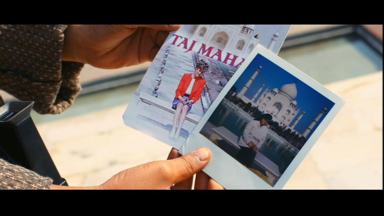

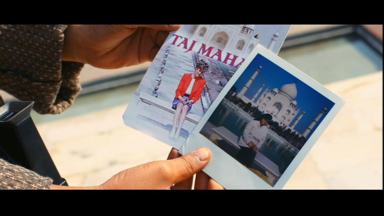

The consistent use of “script mixing” (Bhatia and Baumgardner 387) as an “attention-getter” (Bhatia and Baumgardner 387) sees a plethora of occurrences in the film evident in the visuals. Here, crucial cinematic details are proffered bilingually further confirming that “language in cinema is complex and multifaceted” (Dissanayake 395). This same strategy occurs on signs outside the Taj Mahal (Figure 19).

Figure 19

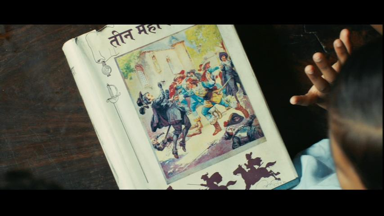

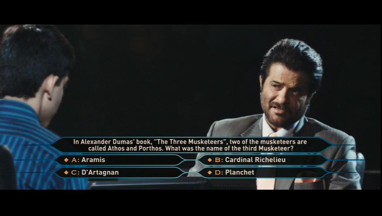

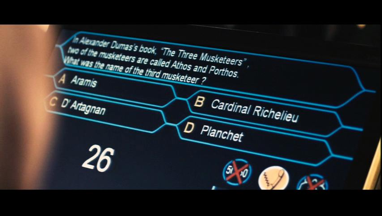

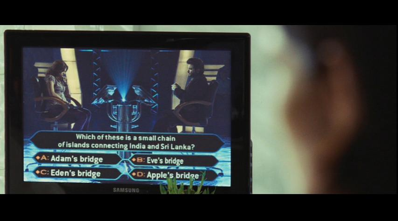

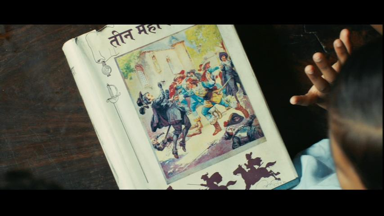

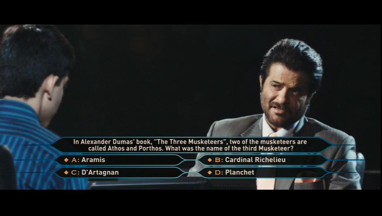

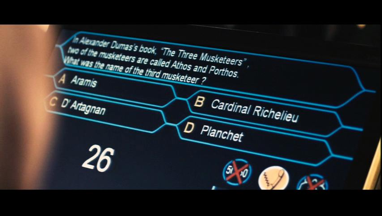

What these examples demonstrate is the use of visual English as cinematic strategy to “meld both national and cosmopolitan influences” (Cowen 101) in the service of a “promulgated western Ethos” (Cowen 101), which seems to be visually rendered for audience members as a “synthetic polyglot product” (Cowen 101). Also innovative is the linguistic glocalization of western literary tropes such as The Three Musketeers - a literary allusion missing in the original novel from which the film is adapted, but which is astutely worked into the filmic script in what can only be conceived as a clever homage to French stakeholders (Pathe controlled international distribution). Consider the filmic effort involved in this endeavor. The title is first rendered visually in Hindi (see Figure 20):

Figure 20

This Hindi title is then followed by a visual English reminder in the form of a titular focus - spelled out in English lettering as “The Three Musketeers.” Next, we have a reminder in both languages - an innocuous scribble of the titles on a blackboard. Yet another narrative reminder occurs verbalized in Hindi and rendered across the screen in visual English in the form of “she could be the third musketeer.” This western literary trope constitutes the final nail-biting, million-dollar question - occurring as a trademark still-shot occupying a third of the screen space, and eventually all of the screen space (see Figures 21 and 22).

Figure 21

Lest audience members forget, visually prominence is sustained in the form of a zoomed-in cinematic still. The audience “reads” the on-screen English while Jamal ponders.

Figure 22

Syncretization

Synchronizing Sound: Global Soundtracks

No one can discount the strategic use of music in film. Dissanayake goes so far as to insist that “language and soundtrack fulfill far more significant roles in film diegesis than such common assumptions would have us believe” (395). For Indian audiences however, “songs are perceived as the quintessential 'commercial' element in a film” (Ganti 79). As Garwood reiterates, “musical sequence has been a key component of the Bollywood movie” (169).

When prompted about his decision to incorporate the trademark Bollywood dance routine in Slumdog Millionaire, director Danny Boyle replied: “You cannot leave without a dance. You cannot. It would be like making a film in America without a motorcar” (Beaufoy, Boyle, and Feld 142). After all, Bollywood is synonymous with “big budget, song-laden productions” (Garwood 171). While song and dance routines form a salient component of the filmic narrative in Bollywood (Dissanayake 398), more research is pointing to the “emergence of the songless Bollywood movie as a commercially viable form” (Garwood 169) particularly as this pertains to “the growing economic power of a particular niche audience” - “a new urban middle class” (Garwood 170) in India - one of the audiences targeted in Slumdog Millionaire.

As a consequence, there is an importing of Hollywood soundtracking styles into the film so that, with the exception of the final credits, there is no actual “picturization of song” (Garwood 170) in the film, but rather an aural backgrounding of soundtrack which scaffolds the unfolding narrative. What we have, in effect, is an incorporation of pop songs utilized as montage sequences so that rather than experience the interruptive narrative of the visualization of song so endemic to the Bollywood filmic narrative - what Gopalan has astutely called a “constellation of interruptions” (3), Western and Indian audiences alike in Slumdog Millionaire are treated to a "visual organization" of a soundtrack heard but unpicturized - a Hollywood sound sequence. This strategy according to Garwood prompts in viewers the following mimetic logic: “a distanced vantage point from which to take stock of the various narrative situations” (179) and an understanding of “the thematic links between them” (179).

The soundtrack of Slumdog Millionaire is predominantly English, featuring prominent songs performed in English by British pop star MIA. The use of this soundtrack coupled with A.R. Rahman's score, and the finale Bollywood-style dance sequence hybridizes music in the film. In addition, the final dance routine with its typical “lip-synching and picturization” (Garwood 180), while appropriately exotic to Western audiences, appeals completely to Indian audiences familiar with such “visual correlatives of on-screen dancing” (Garwood 178). This choice of picturization for the final credits results in a film with “an internationally acceptable aesthetic” (Garwood 173). Perhaps this is what explains Boyle’s quandary as to the specifics of the inclusion of the solo song and dance routine into the filmic narrative. As his explanation illustrates, a Western sensibility seems to guide his narrative logic:

So the key was whether we should put it inside the film, as one of the questions linked to a question, for example (we thought there would be a clue in a song and dance that would maybe answer a question, but it did not work out that way). Or whether we put it at the end of the film, as it is right now. So we decided to put it at the end of the film and celebrate that love. It is absolutely genuine. Their love of movies, dancing and song is something to be absolutely celebrated. (Beaufoy, Boyle, and Feld 142)

The strategy worked. Film critic Sragow sings his praise with the following: “Nothing in this film is clichéd...Boyle brings down the curtain with a musical number that registers as a gift from movie heaven. He breaks your heart, then heals it - and sends you out with a song” (1). Here we see an astute utilization of glocalization strategies, what Tyrrell has labeled the “omnibus” or “masala” (271) form of Bollywood filmmaking, which successfully combines “melodrama, action, comedy, social commentary and romance...juxtaposing intensely tragic scenes with jolly song and dance numbers, jolting the viewer from one extreme of feeling to another (an aesthetic similarly inherited from Sanskrit theater” (271). (See Dissanayake on page 398 who attributes this filmic feature to the influence of Parsi theater).

Why the need to include this final song? The answer lies in the commercial role of picturized songs for Indian audiences. According to Garwood, “the song sequence may be seen as local interventions which self-consciously press the viewer into local cinephiliac acts” (181). These "cinephiliac" acts are reflected in the commercial success of the soundtrack both in India and abroad. The Indian reception of the soundtrack emerges in the proud claim by Sengupta who describes Rahman’s score as “weaving sounds from all over the world with a deeply Indian sensibility” (5). Indian audiences saw India in the soundtrack. Indeed, in his acceptance speech at the Academy Awards, Rahman dedicated one of his two Oscars to India. For screenwriter Simon Beaufoy, “The mystery that was Bollywood’s singing and dancing finally made utter sense to me,” further adding, “In this magnificent country of extremes, why would you not sing, why would you not dance?” (Beaufoy, Boyle, and Feld v). The music from Slumdog Millionaire swept the Oscar stage: best song, best soundtrack, and best sound mixing.

The careful marriage of the cinematic vision of a British director relying on a British- derived script adapted from a novel authored by an Indian writer set to a film score created by an Indian musician relying on British and Indian musical-might within a filmic screenplay masterfully adapted to Indian sensibilities by an Indian co-director’s stock of cultural expertise provides a prime example of what Cowen calls “cinematic clustering” (87) at its best - a filmic tool entailing “the strategic use of cinematic talent from around the world” in a bid to “strengthen the market position” (87). Journalist Dhaliwal quotes Bollywood icon Amitabh Bachchan’s recognition of this strategy in his cinematic take on the film, namely, that “the Slumdog Millionaire idea, authored by an Indian and conceived and cinematically put together by a westerner, gets creative global recognition.” While cinematic clustering is not inimical to diversity, it effectively utilizes linguistic and cultural diversity in the service of linguistic and cultural homogeneity. Consider the explanation of the role of the co-director, Loveleen Tandan, as explained by Boyle:

I realized when I was working with her that I needed her on the set every day.... And that was not just for the kids who only spoke Hindi, it was for everything, really. And I could test things against her, cultural elements and stuff like that; also when I knew I wanted to make a mistake and do something inaccurately, because you do that - films have their own justice and logic, which is not applicable to the country, necessarily. She was someone I could bounce off, who I trusted, and she was also able to tell me the truth. (Beaufoy, Boyle, and Feld 139)

For critics, this melding of global talent to render a universal crowd-pleaser had a huge pay-off. Note film critic Morgenstern’s response to this melding of motifs: "This perfervid romantic fable...draws freely, often rapturously, from Charles Dickens, Dumas pere, Hollywood, Bollywood, the giddiness of Americanized TV, the cross-cultural craziness of outsourced call centers" (1).

Print Capitalism: Forefronting Iconicity

Dissanayake argues, “Formations of nation state and cultural production are inextricably linked” (404) when it comes to cinematic representation. Consequently, we cannot discount the role of what he calls “print capitalism” (404) in underscoring the iconicity of place and paraphernalia in the construction of mimetic desire. Consider the product placement of a cell phone where visual Englishing cleverly ties the "need" for the product into the unfolding narrative at the very same time as it serves as an effective advertisement for a specific product for film audiences. The movie-makers had to be acutely aware that “India, currently the world’s twelfth largest consumer market, is predicted to be the fifth-largest by 2025” (Gama 23).

Figure 23

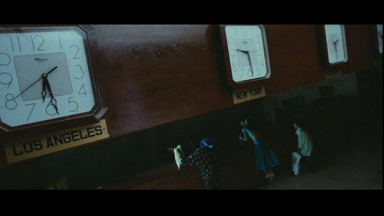

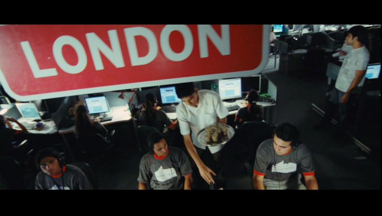

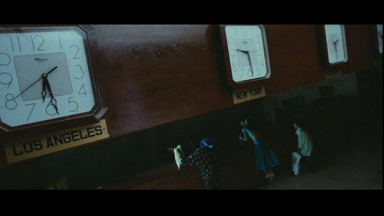

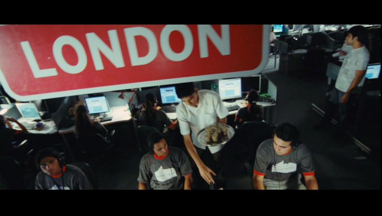

The effective use of such visual marking comes in the manner in which the geographical iconicity of the West is visually and verbally forefronted in Slumdog Millionaire. The cities of Los Angeles, New York, and London are visualized as are specific streets in Britain which are made visually prominent in several scenes in the film (see Figures 24-28]. Here we see "iconic" place names labeled and then "relabeled" for viewing audiences. The visual setting of a call-center - a key global player - make the visualizations particularly powerful serving both as verbal and visual reminder of India in the world, and the World in India. After all, as Gama concedes of India - “this call center superpower carries out back-office processing for over 40 percent of the world’s top 500 corporations” (23).

Figure 24

The magnitude of these places is accomplished via a careful contrast established between the diminutiveness of Indian children looking up [pun intended] at these massive, and seemingly innocuously labeled Western place-banners (see Figure 24). Here, the English labelings of Los Angeles, New York, London, and later Cambridge, take on special semiotic meaning.

The intentional choice of place as cinematic wallpaper to instigate mimetic desire comes in the descriptions proffered in the actual shooting script for the call-center scene as detailed by screenwriter Beaufoy who writes in the following meticulous prop details: "On the walls are pictures of London, Tony Blair, red telephone boxes, the Yorkshire Dales, the Highlands - a snapshot of tourist Britain...Each section of the room has a banner with a British city’s name on it and various mock sign-posts for the different aisles" (Beaufoy, Boyle, and Feld 117-118).

We cannot miss the shot of Big Ben in the montage which assaults the eyes, a shot which is both verbally and visually inscribed on celluloid (see Figure 25).

Figure 25

In what can only be seen as a brilliant use of cinematic montage, audience members are taken through the streets of England cleverly adapted as the cubicle spaces of an Indian call-center. A whizz of street names forms the cinematic montage - “The High”; “Trafalgar Square”; "Pembroke Street"; "Broad Street" - even "The East Indian Docks" - spell out the potent visual "cartel of imagery" (Price 27) that hits audience eyes. The cinematic visualization carefully spotlights these place names - city names which take up all or most of the screen space (see Figures 26-28).

Figure 26

Figure 27

Figure 28

Compare, for instance, the peripherization of Indian locale in the movie which, in contrast to the prominence of "global space," emerges as an ancillary, fleeting moment on TV, barely seen by Latika, or even the audience (see Figure 29).

Figure 29

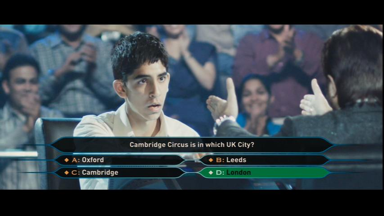

This careful visualization of place exists for the cinephilic appeal it can potentially induce in an emerging traveler class in India. How else can we explain the ways in which knowledge of place becomes a quiz item for the viewing audience and confirms, in essence, claims by Garwood as to “the commercial impulse behind the invitation of such a tourist gaze” (176)? As if the minimizing of the local is not enough, the visual forefronting of "faraway" place names is verbally reiterated in excruciating detail on the part of Jamal who "talks out" his answer to a query at the very same time that these place names whizz by in the form of a visual parade of icon-construction on the silver screen (see Figures 30 and 31).

The script reads as follows:

Jamal: Well, Oxford has Broad Street, Saint Aldates, Turl Street, Queen Street, The High and Magdelene Bridge - which is pronounced Maudlin, so - ... And it’s not Leeds, because there’s Elland Road, Kirgate Market, Commercial Street, St Peter’s - ... Well I don’t think its Cambridge...Too obvious. There’s definitely an Oxford Circus in London, and there’s a rowing race between Oxford and Cambridge so there’s probably a Cambridge Circus too. I’ll go for D) London.

Prem: That’s the logic that’s got him this far, Ladies and Gentlemen. Who are we to argue?

Figure 30

The color-coded shift from orange to green to indicate the chosen answer educates at the very same time as it tempts audiences, luring them into global space. The use of a foreign locale to spark mimetic desire - a bid to “solicit our interests as tourists, albeit virtual tourists travelling the world within the closed confines of the movie theater” (Gopalan 129) - is a cinematic function clearly at work in Slumdog Millionaire.

Figure 31

This same icon-construction emerges in another powerful visual reminder, featuring a global icon juxtaposed against a local space (see Figure 32). The visual reminder of "Shy Di" - confirms the following of film: "The export of meaning is not just a matter of viewer reception. Many nations place special importance on the international profile they can establish with their audiovisual exports...which are fostered as a form of cultural diplomacy and for intrinsic economic reasons" (Sinclair, Jacka and Cunningham 10).

Figure 32

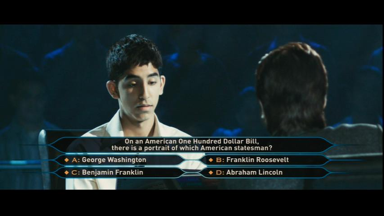

Dollars and Sense

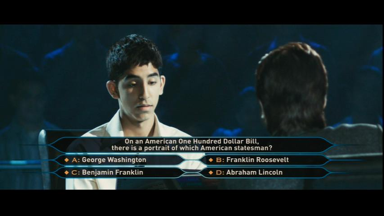

Lest the producers worry that there is too much of Britain in the film, we are given an equally healthy dose of American iconicity. The young Jamal after being brutally beaten in a car theft scene exclaims to two innocent American tourists: “You wanted to see a bit of real India - here it is!” The American tourist replies, “Well, here is a bit of the real America, son!” - and then hands him a hundred dollar bill. This act becomes the perfect narrative segue to provide a visual anatomy of the hundred dollar bill - a cinematic feat accomplished via a series of repetitive visual and verbal reminders taking up countless minutes of viewing time. The visual metaphor of the dollar as a trope for “escape from unenlightenment” (Garwood 174) is powerfully reiterated time and time again. We first get a verbal voice-over at the scene of the quiz show: “On an American One Hundred Dollar Bill, there is a portrait of which American Statesmen?” asks the quiz show host. This voice-over allows for ample opportunity to focus on the visual English with which the scene is synchronized. As the question is asked, the camera switches to Jamal, and we "see" the question again (see Figure 33).

Figure 33

At this point, there is small-talk, with a cinematic-still of the question lingering in the eye of the camera, and the viewing audience. Cinematic prominence in terms of this question occurs yet again via a visually powerful strategy of cinematic voyeurism wherein Latika watches this scene unflold. Like Latika, audience members are treated to a repeat, a voyeuristic "re-seeing" of the prompt about the anatomy of the dollar. The global utility of the dollar in contrast to the seeming worthlessness of the rupee for these street urchins - after all, the climax of the film sees a torching of a tub-full of rupees by a guilt-ridden brother - emerges in the following dyad which unfolds between a doubting police officer and the older Jamal:

Policeman: Who’s on a 1000 rupee note?

Jamal: I don’t know

When Jamal is, in fact, confronted with a thousand rupee note, he scoffs with “I’ve heard of him” (see Figure 34).

Figure 34

Contrast this attitude of distance with the proximity and affiliation displayed towards the dollar. After all, a child is made to "lovingly sniff" a note in another scene designed to cinematically showcase the one hundred dollar bill to viewing audiences (see Figure 35):

Friend: What’s on this note? Whose picture?

Jamal: There’s a man, he’s bald on top with long hair on the sides, like a girl.

Friend: Benjamin Franklin! [excited! - Grabs the note and lovingly sniffs it]

Could this be an example of a “courier of Western values to the Indian audience” (Tyrrell 328) that research alludes to?

Figure 35

This palpable scene confirms the powerful manner in which Slumdog Millionaire prompts “domestic viewers with glimpses of a world of consumerist abundance to which they should aspire in the era of post liberalization” (Garwood 176). That Jamal is able to "earn" dollars which he can then use to better the life of a fellow-Indian, confirms Cowen’s observation of the workings of cultural exportation in and through film - an effective exportation of “the American ethos of commercialism and individualism” (80).

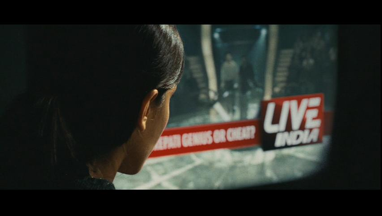

Nothing in this film is accidental. As it reaches its suspenseful climax, the frequent use of the homograph “live” (see Figure 36) steeped in the trademark voyeuristic still-shots beckons India to in fact live! - a final invitation for viewers to engage in “consumerist abundance” (Garwood 346-347) (see Kaur 199; Alessandrini 316). After all, India is “a major player in the global economy, ranking fourth in terms of purchasing power, according to the IMF and the World Bank, with an annual GDP of US$3.8 trillion” (Gama 23).

Figure 36

Spectacularization:

Cultural Knowledge: Adaptation and Valuation Patterns

We have already seen how local musical talent has been effectively glocalized in this film. This same strategy is at work in the filmic content - the actual particulars of the screenplay adaptation as contrasted with Vikas Swarup’s original novel, Q & A - on which the film is based. Of particular salience are three adaptation strategies: what is included in the screenplay adaptation; what is excluded; and finally, what is augmented. In an analysis of filmic content - what is adopted versus what is adapted we see an astute melding of linguistic, cultural, and symbolic capital (Bourdieu 128-129).

The use of a cultural schematic which is partially “localized, domesticated and indigenized” (Sinclair, Jacka, and Cunningham 5) to uphold a semiotic sensibility which is majorly globalized, internationalized, and cosmopolitanized comes in an examination of the filmic adaptation of the screenplay prompts used from the novel. Consequently, it is important to note that 90% of the questions (or nine of the questions) in the film have been altered from the novel either in minor terms, or changed in major ways. Only 10% of the question-content (one question) is wholly adopted from the novel. Additionally, the concomitant monetary valuation of each question is anything but innocuous. That locally known and “indigenously based” (Tyrell 270) knowledge serves second to the ultimate value of global knowledge comes as no surprise. Stated differently, the highest valued questions test cosmopolitan rather than local knowledge.

Suffice it to say that while the novel critiques American and Australian characters, these characters are suspiciously missing in Simon Beaufoy’s filmic adaptation of the novel. Below are some of the actual questions in the novel Q & A compared to the questions in the filmic script of Slumdog Millionaire all of which reflect a careful “claim on the cultural capital” (Garwood 181) of both domestic and Indian audiences - “two of the largest viewing audiences in the world” (Cowen 79). It has to be reiterated that “Bollywood is the most prolific film industry in the world” (Tyrrell 261). Consider the first interrogative in the film (see Figure 37), which has been changed to include an icon of Bollywood - Amitab Bachchan - described by Gama in the following terms: "Known as Big B, Bachchan reigned supreme in Bollywood from the ‘70s to the mid ’80s and continues to be the Badshah (literally ‘great king’ but used in the sense of ‘veteran’) of Indian showbiz. He was voted the ‘Greatest Star of the Millennium’ by a BBC online poll in 1999 and in 2000 became the first living Asian to have been immortalized in wax at Madame Tussauds" (36). While we never see an actual encounter with Amitabh Bachchan (he was quite displeased by the film) (Dhaliwal), we are given a montage scene in which he is visually glimpsed - a strategic inclusion on the part of the director for Indian viewer-eyes. As an aside, both the script and the film carefully avoid providing a list of Indian actor names (see Figure 37).

Figure 37

|

Value |

Question #1 |

Q&A |

Rs. 1,000.00 |

Name the blockbusting film in which Armaan Ali starred with Priya Kapoor for the very first time? Was it (a) Fire, (b) Hero, (c) Hunger, or (d) Betrayal? (Swarup 33-34) Answer: (d) Betrayal |

Slumdog Millionaire |

1,000.00 |

Who was the star of the 1973 hit film Zanjeer? |

The shift in the second question to patriotic trivia about India is also strategic, allowing for a cinephilic interaction on the part of Indian audiences (see Figure 38).

Figure 38

|

Value |

Question #2 |

Q&A |

Rs. 2,000 |

What is the sequence of letter normally inscribed on a cross? Is it (a) I R N I, (b) I N R I, (c) R I N I, or (d) N I R I (Swarup 52) Answer: (b) I N R I |

Slumdog Millionaire |

Rs. 4,000 |

The national emblem of India is a picture of three lions. What is written underneath? Is it A) The Truth alone triumphs. B) Lies alone triumph. C) Fashion alone triumphs. D) Money alone Triumphs. Answer: A) The Truth alone triumphs. |

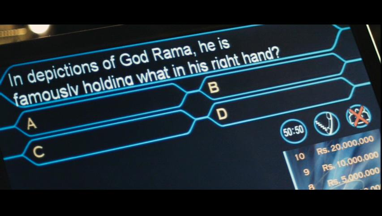

The third question appeals to the religious sensibilities of a nation with the following demographics: “most followed religions: Hinduism (81.3%), Islam (12%), and Christianity (2.3%)” (Gama 24, see Figure 39). Also key to note is that while the protagonist of the novel is named “Ram Mohammed Thomas” (Swarup 4) an eponymous homage to all three Indian religions - the filmic script of Slumdog Millionaire carefully changes the hero’s name to Jamal Malik - he is not Christian. Is this an appeal to the majority religions of India? This filmic detail lends credence to the claim that the incursion into Bollywood has to consist of a three-pronged strategy: “aesthetic and cultural as well as political” (Tyrrell 270).

Figure 39

|

Value |

Question #3 |

Q&A |

Rs. 5,000 |

Which is the smallest planet in our solar system? Is it (a) Pluto (b) Mars, (c) Neptune, or (d) Mercury

Answer: (a) Pluto (Swarup 72) |

Slumdog Millionaire |

Rs.16,000 |

In depictions of the God Ram, he is famously holding what in his right hand? Is it A) a flower. B) a scimitar. C) a child or D) a bow and arrow. Answer: D) a bow and arrow. |

The reminder of the Raj sees strategic inclusion in the fourth question. That this is, in fact, an "accidentally on purpose" inclusion comes in screenwriter Beaufoy’s own detailings:

I first visited India over twenty years ago. I was eighteen, alone and rather frightened by this vast land. But among the strangeness lay a comforting familiarity. Connaught Place could be Bath on a very sunny day, Victoria Terminus a grander noisier St. Pancras; everywhere people spoke to me in English, knew about London, Lords, Manchester United. Echoes of Britain’s rule were distant but ever present.

Then I read Vikas Swarup’s extraordinary book Q & A. Nothing that I thought I knew about India lay in these pages. Intrigued I went to Mumbai. No trace of the Raj remained, not even the name Bombay. In its place was a city of gangsters.... (Beaufoy, Boyle and Feld v)

This nostalgia for the past is encoded in several montage shots in the film and captured in the wording of the fourth question (Figure 40).

Figure 40

|

Value |

Question #4 |

Q&A |

Rs. 10,000 |

Surdas, the blind poet, was a devotee of which god: (a) Ram (b) Krishna, (c) Shiva, or (d) Brahma

Answer: (b) Krishna (Swarup 102) |

Slumdog Millionaire |

Rs.64,000 |

The British architect Frederick Stevens designed which famous building in India? Is it A) The Taj Mahal. B) Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus. C) India Gate. D) Howra Bridge. Answer: B) Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus. |

Boyle takes great pains to give us a vestige of the Raj; Jamal leans against the landmark. In an interview with Rob Feld, Boyle confesses to a tugging nostalgia for this British past:

This is a kind of admission, but because the British ruled India until 1948 [sic], quite recently in historical terms, you go there and expect people to remember you... But they just do not see you now. They see their society and tiger economy hurtling forward at such a pace that they see themselves as Brazil, America, Russia, China. That is where they see themselves, against these big economies. Either established, like America or arriving. And you, the British, are an anecdote, a footnote. That is the first thing I felt, very strongly, almost immediately. (Beaufoy, Boyle and Feld 137)

On a related note, while some critics have argued that the film is a “peddler of the country’s poverty,” “slum slam,” “poverty porn” (Wax 1), and caters to a nascent western “appetite for slum tourism” (Sesser 5), others have gone so far as to file legal complaints “in Indian courts against Boyle and the Indian actors, contending that the film’s title is discriminatory and harks back to British rule, when they called Indians dogs” (Wax 1). Interestingly, the word "Slumdog” has since been used for similar dysphemistic insult at immigrant Indian IT workers by American talk show host Rush Limbaugh (Thompson).

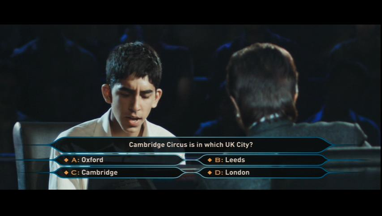

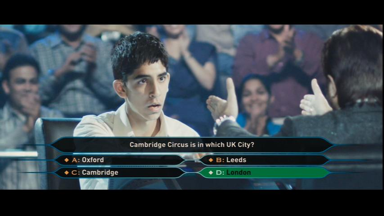

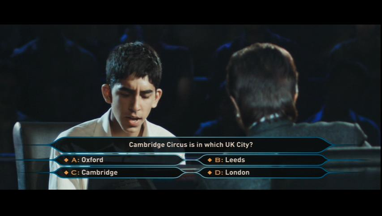

It is only question 7 in the novel which is wholly adopted even though its placement in the film occurs as Question 8. Instead, the script uses the visual space of question 7 to sell the topographic space of the West to the East - a point already examined earlier (see Figure 41).

Figure 41

|

Value |

Question #7 |

Q&A |

Rs. 200,000 |

Who invented the revolver? Was it (a) Samuel Colt, (b) Bruce Browing, (c) Dan Wesson, or (d) James revolver? Answer: (a) Samuel Colt (Swarup 165) |

Slumdog Millionaire |

Rs.

2,500,000 |

Cambridge Circus is in which UK city? Is it A) Oxford., B) Leeds. C) Cambridge. D) London. Answer: D) London. |

In addition to the visual montage of the topography of these British cities, audience members are given minute geographical details of Britain as Jamal is made to do a metacognitive think-aloud for question #7 carefully valued at 2.5 million rupees.

The shift in question 9 from local knowledge to global knowledge in the field of cricket is also important to note (see Figure 42).

Figure 42

|

Value |

Question #9 |

Q&A |

Rs. 1,000,000 |

How many Test centuries has India’s greatest batsmen, Sachin Malvankar, scored? Your choices are (a) thirty-four, (b) thirty-five, (c) thirty-six, or (d) thirty-seven?”

Answer: (c) thirty-six (Swarup 209) |

Slumdog Millionaire |

Rs.

10,000,000 |

Which cricketer has scored the most first class centuries in history? Was it A) Sachin Tendulaka. B) Ricky Ponting. C) Michael Slater. D) Jack Hobbs? Answer: D) Jack Hobbs. |

As already mentioned, the novel had thirteen questions - an unlucky number in the West. In the script, audiences are treated to only ten questions - with the final, most valued question being on a Western aesthetic trope (see Figure 43).

Figure 43

|

Value |

Question #10 |

Q&A |

Rs. 10,000,000 |

Neelima Kumari, the Tragedy Queen, won the National Award in which year? Was it (a) 1984, (b) 1988, (c) 1986, or (d) 1985?”

Answer: (d) 1985 (Swarup 236) |

Slumdog Millionaire |

Rs.

20,000,000 |

In Alexandre Dumas’ book, The Three Musketeers, two of the musketeers are called Athos and Porthos. What was the name of the third musketeer? Was it A) Aramis. B) Cardinal Richelieu. C) D’Artagan. D) Planchet. Answer: A) Aramis. |

Conclusion

So, to recapitulate, how do you sell a film to a global audience? By selling English - along with America, Europe, Western icons, and local color - on the silver screen. How then do you sell English - as well as these other items - on the silver screen? Is it by a. Spotlighting, b. Synchronization, c. Spectularization, d. Syncretization, OR e. all the above? The answer is E, of course, because these forces all work together to globalize the product, thus appealing to the widest possible audience, which results in accolades: both aesthetic and economic. Slumdog Millionaire, nominated for ten 2008 Academy Awards, “captured 8 Oscars” (Chopra 18) - including the most coveted award: Best Picture. The financial consequences of visual Englishing have been lucrative to say the least. Produced on a shoestring budget of a mere $15 million (Wax 1), Slumdog Millionaire grossed “2.8 million in just the opening weekend in India alone where it played on 350 screens” (Wax 1) and saw an equally “rapturous reception in Britain and America” (Dhaliwal). Recent figures show that the film has “taken in nearly $250 million globally so far” (Chopra 18) - a whopping 600% profit margin which does not include its soundtrack sales. The aesthetic and economic genius of Slumdog Millionaire lies in moviemaking which results in “films that are entertaining, highly visible, and have broad global appeal” (Cowen 74).

Slumdog Millionaire has demonstrated how linguistic desire can constitute part of the spectrum of mimetic desires for which dream machines can successfully be utilized. This film demonstrates how cinematic spotlighting of visual English - casting visual English as a prominent player on the silver screen - can work to bring a Bollywood inspired film into a world marketplace. The careful adaptation of the locality of Indian lingua-culture to derive a globally-driven cultural product can indeed function to have the desired mimetic consequences. This “spectacularisation of English” in film (Garwood 176) has powerful consequences. Slumdog Millionaire has successfully demonstrated how the seduction of the silver screen can indeed be exploited as a “field of force” (Dissanayake 405) - a global prompt for English fluency. Screen-space cluttering of visual English synthesized with verbal English reflects an astute use of language as filmic strategy - as linguistic capital. Consequently, English becomes both filmic instrument and filmic product in global transcultural flows (Pennycook 12). After all, to truly enjoy Slumdog Millionaire, we have to be able not just to speak English, but also to read it.

Works Cited

Alessandrini, Anthony C. “'My Heart’s Indian for All That’: Bollywood Film Between Home and Diaspora.” Diaspora 10.3 (2001): 315-340.

Barnet, Richard J. and John Cavanagh. Global Dreams: Imperial Corporations and the New World Order. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1994.

Beckman, Rachel. “An Out-of-Character Role for Subtitles.” The Washington Post

16 November 2008: M5.

Beaufoy, Simon, Danny Boyle, and Rob Feld. The Shooting Script: Slumdog Millionaire. New York: NewMarket Press, 2008.

Bhatia, Tej. K. and R. J. Baumgardner. “Language in the Media and Advertising.” Eds. Braj B. Kachru, Yamuna Kachru, and S. N. Sridhar. Language in South Asia. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2008. 377-394.

Bourdieu, Pierre. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1984.

Chopra, Anupama. “Stumbling Toward Bollywood.” The New York Times 22 March 2009: AR18.

Cowen, Tyler. Creative Destruction. Princeton: Princeton UP, 2002.

Crystal, David. By Hook or by Crook: A Journey in Search of English. New York: Overlook Press, 2008.

Dhaliwal, Nirpal. “Slumdog Millionaire could only be made by a Westerner.” The Guardian, 15 January 2009.

http://www.guardian.co.uk/film/filmblog/2009/jan/15/danny-boyle-shows.

Dissanayake, Wimal. “Language in Cinema.” Eds. Braj B. Kachru, Yamuna Kachru, and S. N. Sridhar. Language in South Asia. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2008. 395-406.

Gama, Noël. Culture Wise India: The Essential Guide to Culture, Customs and Business Etiquette. London: Survival Books, 2009.

Ganti, Tejaswini. Bollywood: A Guide to Popular Hindi Cinema. London: Routledge, 2004.

Garwood, Ian. “The Songless Bollywood Film.” South Asian Popular Culture 4.2 (2006): 169-183.

Gopalan, Lalitha. Cinema of Interruptions: Asian Genres in Contemporary Indian Cinema. London: BFI Publishing, 2002.

Jurgensen, John. “The Co-pilot of Slumdog - How a Little-known Indian Filmmaker helped shape the acclaimed movie.” The Wall Street Journal 9 January 2008: W6.

Kaur, Ravinder. “Viewing the West through Bollywood: A Celluloid Occident in the Making.” Contemporary South Asia 11.2 (2002): 199-209.

Lakshmi, Rama. “Bollywood, Hollywood Tightening Film Ties; A ‘Natural Synergy’ seen in the Markets.” The Washington Post 7 March 2009: A8.

Morgenstern, Joe. “Slumdog Finds Rare Riches in Poor Boy’s Tale - Dickens weds Bollywood under Boyle’s Expert Hand.” The Wall Street Journal 14 November 2008: W1.

Pennycook, Alistair. Global Englishes and Transcultural Flows. New York: Routledge, 2007.

Price, Monroe E. “New Role of the State.”Media and Sovereignty: The Global Information Revolution and its Challenge to State Power. Ed. M. Price. Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2004. 27-36.

Sengupta, Somini. “Indians Embrace the Triumph of ‘Slumdog’ as a Victory for Their Country.” The New York Times 24 February 2009: C5.

Sinclair, J, E. Jacka and S. Cunningham. “Peripheral Vision.” New Patterns in Global Television: Peripheral Vision. Eds. Sinclair et al. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1996. 5-25.

Slumdog Millionaire. Dir. Danny Boyle and Loveleen Tandan. Perf. Dev Patel, Freida Pinto and Anil Kapoor. Fox Searchlight Pictures and Warner Bros. 2009. DVD.

Smith, Ethan. “Slumdog-Remix - The Oscar-winning song ‘Jai-Ho’ is reworked with help from a Pussycat Doll.” The Wall Street Journal 27 February 2009: W2.

Sragow, Michael. “Best Game in Town: Life Events Entangled in Contest in Slumdog.”

The Baltimore Sun 21 November 2008: C1.

Swarup, Vikas. Q and A: A Novel. New York: Scribner, 2005.

Thompson, Jessica. "Rush calls Indian BPOs Slumdogs." Times of India 15 April 2009: http://blogs.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/chandnichowktochicago/entry/offended-by-rush-join-the

Tyrrell, Heather. “Bollywood Versus Hollywood: Battle of the Dream Factories.” Cultural and Global Change. Eds. Tracey Skelton and Tim Allen .New York: Routledge, 1999. 260-273.

Wax, Emily. “The Shadow of ‘Slumdog’s’ Success; What does the film owe Child Actors and India?” The Washington Post 31 January 2009: C1.

Wyatt, Kristen. “Bollywood Dance Comes Shimmying into the Gym.” Los Angeles Times 15 March 2009: A11.