|

"It's ugly, but it gets you there." So states a typical advertisement for the Volkswagen Beetle in 1969, featuring a picture of the spacecraft that had piloted the Apollo 11 astronauts to the moon only two weeks prior, and a small VW logo under the single line of text. The advertisement was brilliant in its simplicity and directness, and it went on to become one of Volkswagen's most award-winning ads (Nelson 173). At the time of this ad, it had been nearly twenty years since the Beetle had arrived in the United States. Its initial introduction brought a skeptical eye from the American automobile industry, and rightfully so, as the Beetle was completely backward from what was available in the country at the time. The car was significantly smaller than its American counterparts were, it got thirty-two miles to the gallon, and the engine was located in the rear of the car. Those, and other factors, made the Beetle an odd automobile for Americans, but perhaps that peculiarity added to its social appeal and rapid acceptance by the American car-buying public -- despite the fact that the conflict with Germany in World War II had concluded less than a decade prior.

The success of the Beetle (and other early Volkswagens, for that matter) can be attributed to a number of possible factors, from the consistency within models to the timing around the Vietnam War to the gas crunch of the 1970s. Persistent throughout Volkswagen's early presence in the United States, however, was the advertising campaign. The Volkswagen cars were odd enough, but the advertising campaign surrounding them truly shaped and established the image of what it meant to be a Volkswagen driver. In other words, the campaign set those drivers apart from others, perhaps leaving them open to jeering from their neighbors, but it set them apart nonetheless -- and if the sales figures were any indication, it was only a matter of time before the neighbors picked one up too. As stated in a 1971 Volkswagen advertisement published in Newsweek,

Volkswagen owners may have been laughed at in their funny-looking cars, but they could laugh too, "all the way to the bank" (59).

The Volkswagen campaign succeeded in establishing a brand identity that is still remembered today and that, some would argue, developed their early automobiles into American pop culture icons -- with the VW Beetle and Transporter (van) acting as the flagships. This study examines the impact of the Volkswagen campaign on the culture of the United States during the 1960s and 1970s through the lens of viral marketing. It is true that viral marketing is a current buzzword for the latest advertising trends utilizing existing social networks through the Internet, but the principles behind viral marketing, which will be discussed later, seem to be present within the early Volkswagen campaign -- sans the Internet, of course.

This research relies upon Volkswagen advertisements found in Newsweek magazine from 1959 through 1980, in order to provide perspective on the messages Volkswagen sent to its potential customers and to track any change over time. Newsweek magazine was targeted by Volkswagen's campaign because it was a weekly publication, a fact that also aids us in drawing conclusions about gradual changes in messaging. The first ads in Newsweek appeared in 1959; this study concludes in 1980 because of the changes within the Volkswagen product lineup at that time, the five-year gap from the Vietnam War, the organization’s recovery from an economic slump, and the economic changes that would be brought in with the Reagan administration.

Historical Background

To understand the Volkswagen story is to understand what the organization meant to the German people from Adolf Hitler's time through World War II, and from World War II to the foundational decades of Volkswagen as a corporation separate from its government. Within the story of the Beetle lies Hitler’s failure to deliver on his promises to his people, the resuscitation of the German economy following World War II, and an unlikely success that placed the American automotive industry on edge.

Germany. Even before it arrived on American shores, the Beetle was an odd car in its Vaterland of Germany. While its origins can be traced back to the time of Hitler, and while Hitler was quick to trumpet the Beetle (then known as the KdF Wagon) as a symbol of the socialist republic, no Beetles were ever delivered into the hands of German citizens while he stood in power (McCormick C12; "German Mirages" 20). The first model, supposed to be all ready for mass production, was enthroned on a great flood-lit stage in the automobile show of 1939, and those who observed the daily stampede to inspect the "people's car" saw in the excited eyes of ordinary Germans that this was for them, as the Fuehrer passionately proclaimed on that occasion, the symbol of the national socialist revolution. He lauded the Beetle as a car for the masses, but ultimately fell short on his promise to deliver. In this sense, as Hitler mentioned, the Beetle did stand as a symbol for the German people, but amounted to little more than that during his lifetime. Hitler's lack of involvement with the Beetle, once he was caught up in the affairs of World War II, brings into question the association some attempt to make between the Fuehrer and the little car -- because the Beetle did not truly develop into the "people’s car" until well after Hitler's fell from power, when economic turmoil from the war began to reside, and the Beetle began to be exported internationally. The Beetle may have been born under Hitler's watch, but it was raised

in the hands of the German people during the war, and with the help of the British and Americans afterward (Nelson 97; Spielvogel 12-13).

Indeed, "by one of the ironic jokes history is sometimes tempted to produce, it was the Occupation Forces who, after unconditional surrender, brought Hitler's dream into reality" (Nelson 97). In another twist, many German citizens, while economically recovering from the effects of the war, found themselves focusing on attaining the bare necessities in the aftermath of the war, and thus the prospect of owning an automobile was no longer a priority (McCormick C14). With the war out of the way and Hitler "dethroned," however, the economic situation was looking up for Germans, despite the dust and rubble, because the opportunity for growth still existed. The Volkswagen plant continued to function following the war, and the local population relied upon that production to provide food and shelter for their families. A willing workforce, coupled with the British government's decision to instate peacetime levels of production for their own transportation needs, insured Volkswagen's continued survival in an environment where many existing organizations were being restructured or dismantled. Additionally, with the role of the British in distributing goods to the Allies during the occupation, the Volkswagen factory was able to gain access to raw materials that were in short supply or unattainable to other factories. All was not perfect in the plant, as worker health and supply concerns were still issues, but neither situation was enough to halt total production of vehicles, and the organization was able to churn out 1,785 vehicles in 1945 alone (Volkswagen AG 10-13).

Over the next four years, the factory experienced consistent and large-scale growth, and, in 1949, Volkswagen was producing 46,154 vehicles annually when the British government officially turned the organization over to the German government. By 1950, production reached 90,038, and Volkswagen was “already considered a symbol of West Germany's economic miracle” (Volkswagen AG 24-25; 28; 33). In the mid 1950s, an era of growth and prosperity, the Volkswagen then attempted to make the move into the United States.

Coming to America

In 1949, Volkswagen sold two Beetles in the United States -- according to advertising copy in the 26 December 1960 issue of Newsweek (62). Two is more than zero, but hardly enough to establish itself as a cultural icon. It was not until the mid 1950s that Volkswagen first began to target the United States, establishing dealer networks in order to ensure that there was a proper support system in place for customers as well as ramping up production to meet anticipated demand; advertising, however, was not on Volkswagen's list until the late 1950s, so the major driving force in sales during their first years within the United States was spread by word of mouth (Volkswagen AG 28-29).

A Foot in the Door. Word of mouth can be positive or negative, and the Volkswagen Beetle seemed to be the target of both. As Miles Schofield explains, "Drive home in any other new car and your neighbors will take about 30 seconds to get thoroughly used to the fact that you have just spent several thousand dollars for new transportation" (13). He continues, "Drive a new bug home, and it seems like everybody in the world is either curious, wants to tell you how to take care of it, or cannot understand why you bought it" (Schofield 13). Obviously, this latter comment exemplifies a more negative reaction. However, some attitudes were more positive. This initial reliance on word of mouth also allows us to draw the first parallel between Volkswagen’s advertising design and viral marketing. In the modern environment, viral marketing is described (looking at the similarities between a number of definitions) as involving the utilization of existing social networks to promote a brand or product. The term itself is fairly young, and thus its application is usually described in terms of Internet lingo, where forums, chat rooms, and video hosting websites act as the primary means of disseminating information (Rayport). However, on a simpler level, viral marketing has also been described as no more than "network-enhanced word-of-mouth" (Moore 349). With this frame of mind, it is much easier to conceptualize a modern communication buzzword as being applicable to a 1950s advertising campaign, where face-to-face communication, print media, and radio stations fill in where forums, chat rooms, and video hosting sites do not yet exist. The common theme here is communication being disseminated within the existing social structure, and through this method, the Volkswagen Beetle slowly became the talk of the town, especially amongst the competition.

The Beetle did not blend in very well with what Detroit had to offer. The Beetle was much shorter, generally more fuel-efficient, and had a trunk in the front -- all features that tended to prompt conversation on the street. As U.S. auto manufacturers began to see that the Beetle was gaining in popularity, they recognized Volkswagen had not simply created a fad, but there was real demand within the U.S. market for a small, low-cost car. Even with this recognition, however, they found it very hard to compete at the price point Volkswagen had established ("Sales up Sharply for Foreign Cars" WT11). It is difficult to argue with cost from a sales perspective (a concept that Volkswagen capitalized on in a number of its advertisements), and Volkswagen had a corner on the low-cost segment from the moment it entered the U.S market (Jewell 208).

Advertising

As Volkswagen found success within the United States, the organization turned more of its attention, and newfound profits, toward advertising. A 1959 New York Times article highlighted the fact that Volkswagen had seen a great amount of success thus far in the United States, even with very limited advertising. Despite the lack of advertising in print, Volkswagen did have an advertising agency that it had signed on roughly one year before this article ran, but the campaign that resulted from the venture was deemed unsatisfactory, and both entities parted ways (Flammang 77). This break-up resulted in Volkswagen searching for another agency to represent the organization, which eventually led to a partnership with the Doyle Dane Bernbach (DDB) advertising firm. Little did either organization know at the time, but out of this newfound partnership would appear one of the most award-winning and influential advertising campaigns ever put to print.

Philosophy. With an advertising agency on board, Volkswagen now had the means to establish a corporate identity. Granted, the Beetle had been in the United States at this point for nearly a decade, so the American public may have already had an idea of what they thought a Volkswagen was. However, this advertising opportunity provided the company with a chance to build upon that image, providing feedback to individuals who had already formed an opinion, and letting those who had not formed an opinion know what Volkswagen was all about. The task was daunting, and DDB decided to place it in the hands of Helmut Krone and Julian Koenig.

Krone and Koenig first familiarized themselves with the business philosophy of Heinrich Nordhoff, the managing director of Volkswagen at the time, which is summarized in the following statement from Nordhoff: "Offering people an honest value appealed to me more than being driven around by a bunch of hysterical stylists trying to sell people something they really don't want to have" (qtd. in Flammang 135). Nordhoff's philosophy was the heart and soul of what Volkswagen aimed to represent -- and perhaps the Beetle best embodied this philosophy in tangible form. The car looked the same year after year, despite mechanical upgrades added as years progressed. Cost was kept at a minimum, in order to provide good value for the customer. Parts were kept in stock at Volkswagen dealers for every vehicle they made (back to the very first Beetle) so that drivers had the comfort of knowing they would never be left without a part. Not only that, but the parts were also inexpensive.

The challenge for Krone and Koenig at DDB, was to capture Nordhoff's philosophy and transfer it to a consistent, memorable message. The result was a campaign that was direct, open, and occasionally brutally honest to the point of self-deprecation. Perhaps the most applicable example of this method would be the famous Lemon advertisement. The ad simply featured a picture of a Volkswagen Beetle on the page, with the heading “Lemon.” written under it. The text below the headline then proceeded to describe a number of minor details that had been wrong with the car from the factory, concluding with the message that Volkswagen does not let lemons out of the factory. "We pluck the lemons; you get the plums" (qtd. in Challis 69). The Lemon ad changed advertising. The word Lemon was more than a little contentious. No other car ad; no other ad, ever, had dared to challenge the image of its product in such a direct manner (Challis 69). This ad was only the beginning.

Another advertisement that highlighted different strategy employed by DDB was the Jones advertisement. The ad featured a picture of a Beetle parked on the street in front of a row of houses, with the headline stating, "What year car do the Jones drive?" The text below the headline points out how all Volkswagens look alike, so there is no more pressure for a driver to attempt to keep up with the proverbial "Joneses." The ad states that despite the fact that nearly every part in the Volkswagen had changed over the years, its heart and face had never changed: "Volkswagen owners find this a happy way to drive -- and live. How about you" (Challis 66-67). Koenig was the mind behind this advertisement, and hehad the following to say about its meaning:

"The Jones," says Koenig, "are driving a Volkswagen and the Volkswagen is changing all the time inside, but it is not changing outside, so there is no obsolescence," and therefore, he adds, "no preening ego. You could take an inverse delight in not having to keep up with the Jones, in not responding to Detroit's planned obsolescence -- in not being part of that repetitive, competitive culture. You had your Volkswagen and whether it was a current year or four years old, nobody knew the difference" (Challis 65; qtd. in Challis 65).

Koenig, through his comments and vision in developing this advertisement, hit on a theme that accompanies many early Volkswagen advertisements. This theme seems to portray the concept of a "counter culture," or the idea that the ideals that are being presented in the ads are against the established norm. At the shallowest level, this point could be demonstrated in the “Jones” advertisement by the fact that Volkswagen created a car against the established norm, a car that does not grow old over time, and a car that transcends socio-economic status. At a deeper level, the Jones could represent this counter-culture themselves, with the customers buying into the lifestyle that they recognize and want for themselves. In this sense, Volkswagen unabashedly marketed a lifestyle, and those who subscribed to that lifestyle were thus "converted" to the culture. Volkswagen seemingly sought to brand the consumer as well as its own brand, a strategy which, when examined through the frame of viral marketing, would be the equivalent of an organization creating its own social network, and then leveraging that network to promote its product (and thus nurture the network) (Challis 65). The peculiarity and recognizability of the Volkswagen Beetle (and the Transporter, for that matter) made it effective as a rolling advertisement, where, suddenly, those who were driving were the "haves," and those who only watched were the "have-nots," i.e., a viral campaign in which the spread of the message was so broad that the "infected" become the normal.

The Volkswagen philosophy and the ideals mentioned above were present at the beginning of the DDB advertising campaign and laid the foundation of the road that Volkswagen followed as it ventured forward into the U.S. automobile market. The campaign was ambitious, as it started out with the goal to change American perceptions of what to expect from an automobile and manufacturer. It could be argued that every car company was out to change the world's perception of what a car should be, but Volkswagen actually went out and did it, and they were not afraid to poke fun of themselves (or their customers) along the way.

The Progression of the Campaign: Newsweek (1959-1969)

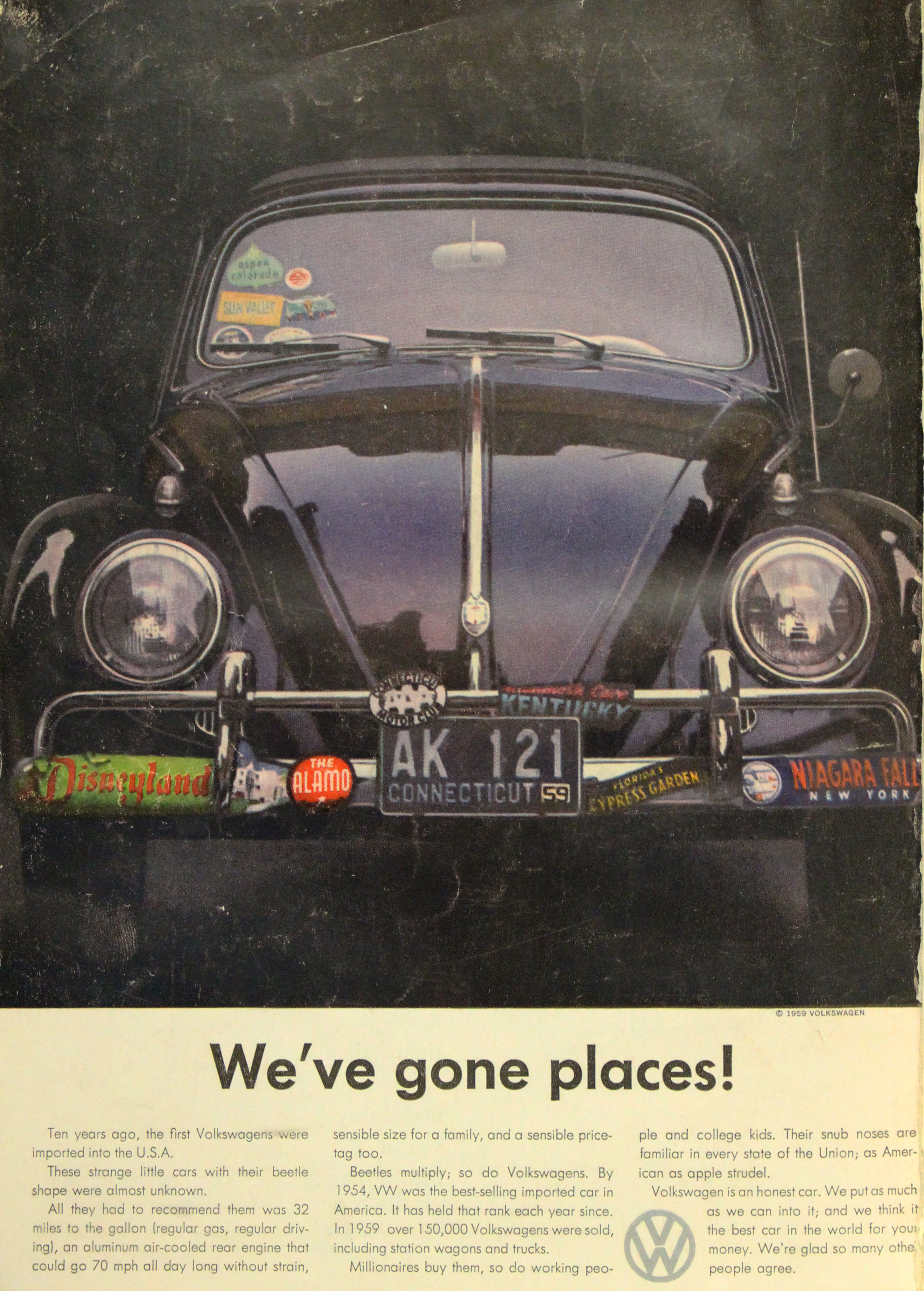

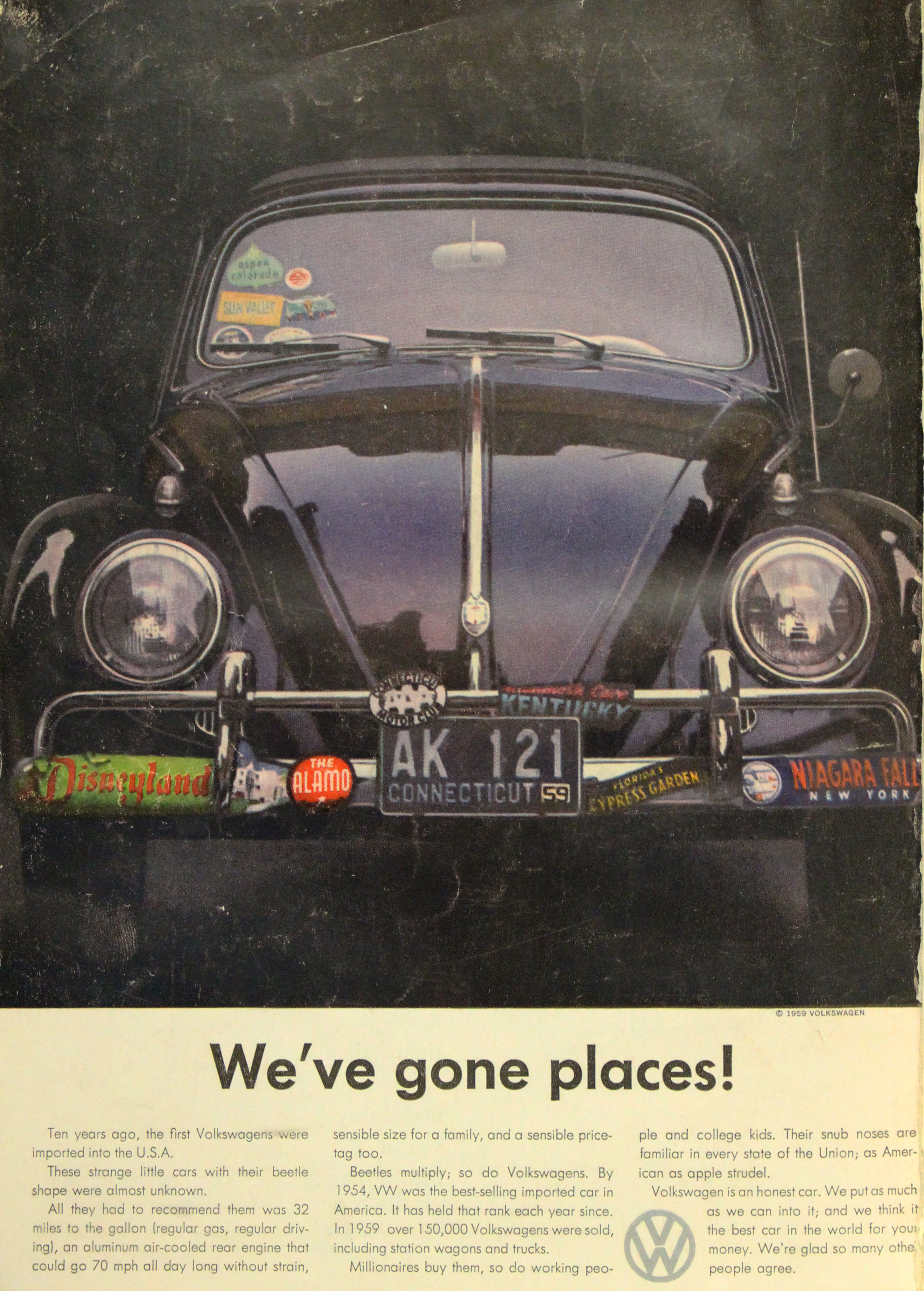

Volkswagen decided to start their campaign in Newsweek with an advertisement on 28 December 1959 featuring a picture of a Beetle covered in bumper stickers, the headline "We've gone places," and a brief description of how far the company had come since it had become the bestselling import car in America every year since 1954 (70; see Figure 1). It is interesting that Volkswagen chose to use this advertisement as a starting point. A statement such as "We've gone places" sends either a message of "trust us because we’ve been around" or a message along the lines of "honey, I’m home." It was Volkswagen's first real foray into the American advertising realm, yet they entered the room like an old friend back from vacation.

Figure 1 Figure 1

What is more interesting still is the fact that Volkswagen went from running that single Beetle advertisement at the end of 1959, to running a string of three Newsweek ads for the Volkswagen Truck in 1960. The Truck advertisements carried the same wit and petulant humor that the Beetle ads became famous for -- with statements such as “Not much for your money,” implying that consumers did not need a radiator, antifreeze, or a large gas tank (29 Aug. 1960, 50; 4 Apr. 1960, 10-11; 11 Apr. 1960, 13). Perhaps Volkswagen knew that people recognized the Beetle on sight, and therefore made the decision to promote the Truck. At any rate, the Beetle was not gone for long.

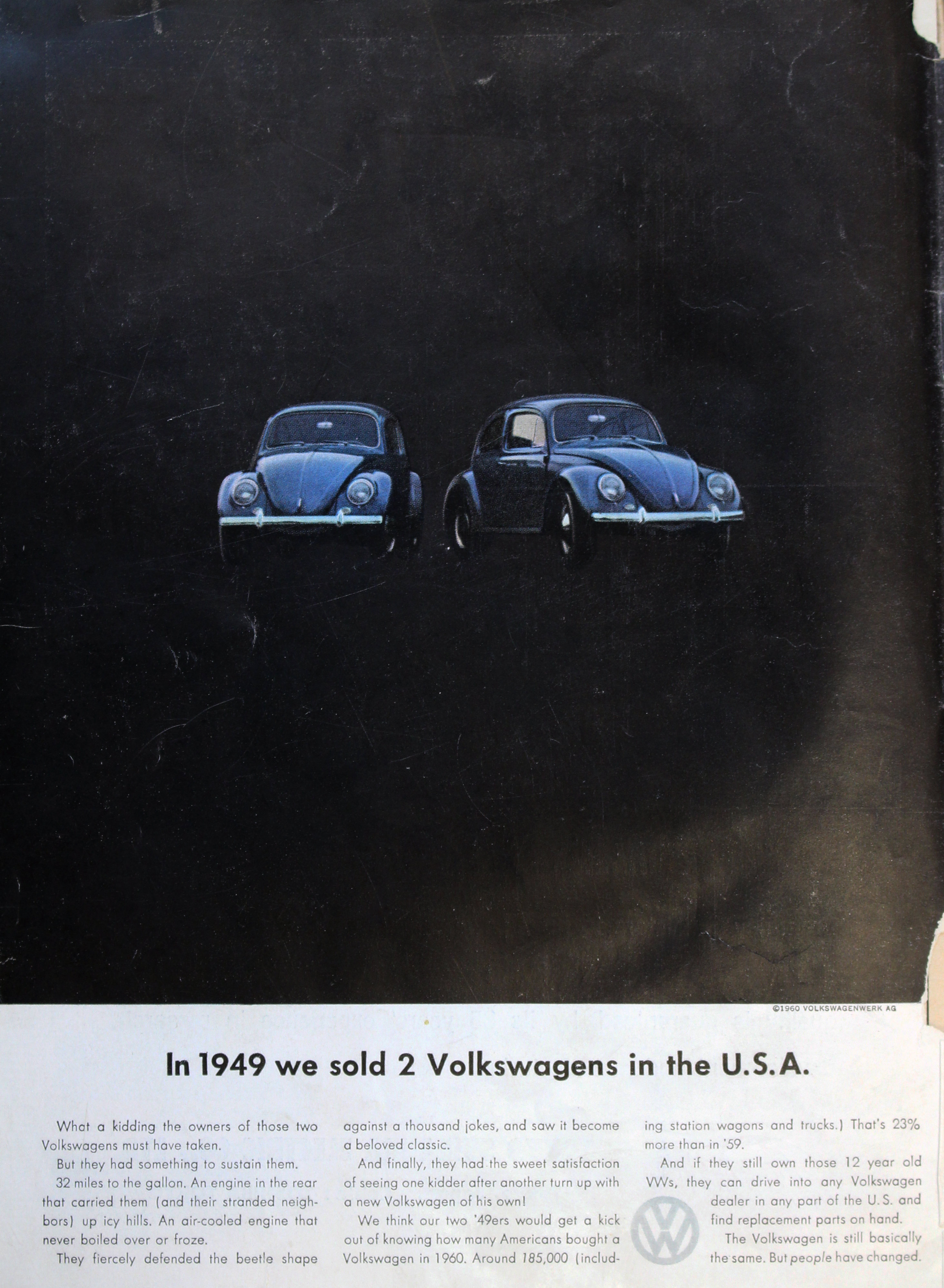

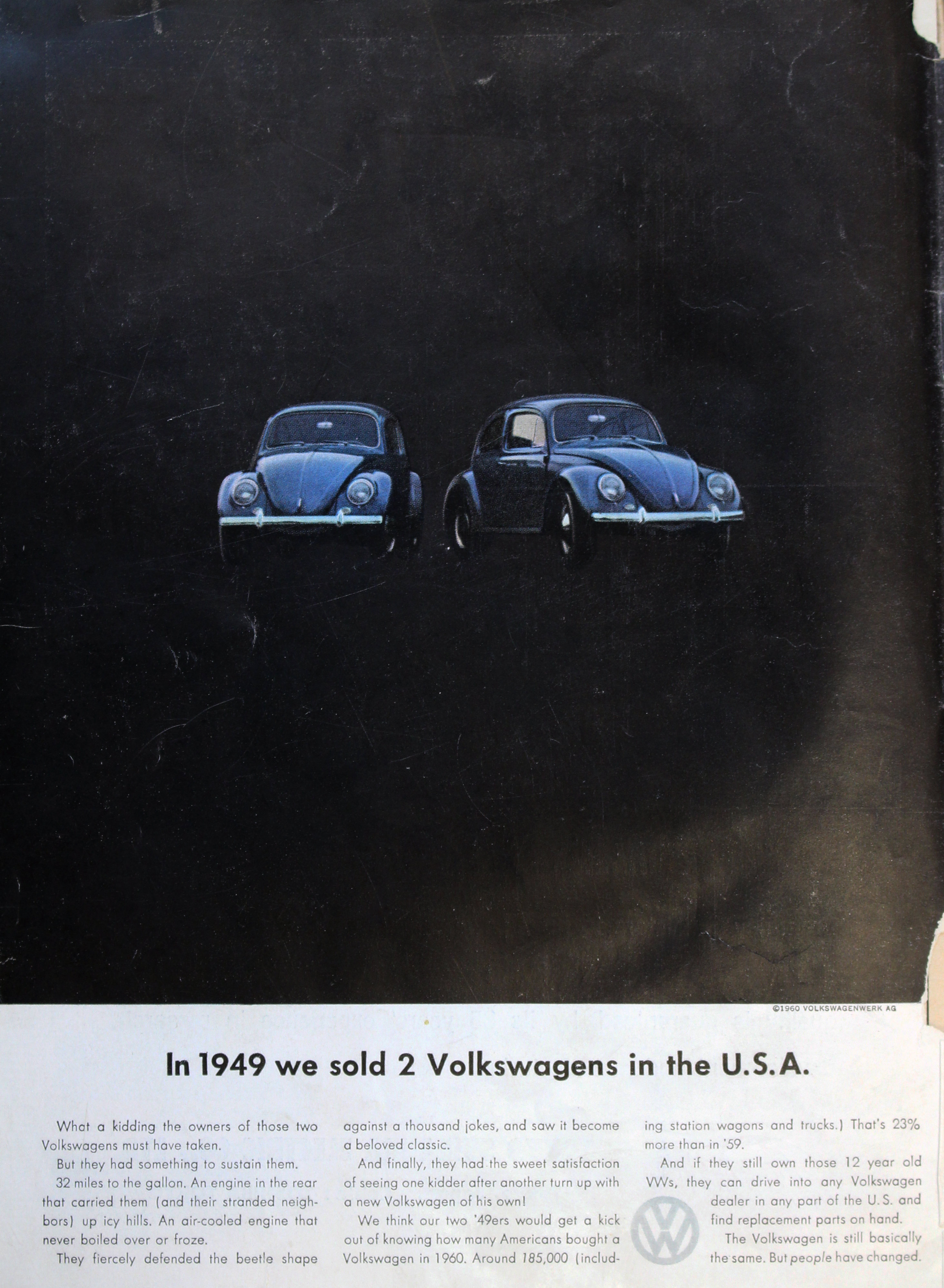

Remember those two Beetles that Volkswagen sold in the U.S. in 1949? Volkswagen did, and they were not afraid to use them. At the end of 1960, Volkswagen ran another Beetle advertisement, this time featuring pictures of the only two Beetles they sold in the country in 1949, with a statement about how much jeering those Beetle owners must have received (see Figure 2). However, over a decade later, Beetles had become a regular sight in the United States, and those owners had gotten thirty-two miles to the gallon that entire time, which may well have made the jeering worth it. Volkswagen concluded this Newsweek ad with the statement that the "Volkswagen is still basically the same. But people have changed," and that was especially true in terms of America's acceptance of the Beetle (26 Dec. 1960, 62). The Volkswagen lineup had entered the mainstream in American culture at this point, and the company was not shy about laying that fact on the table for former "naysayers" to see. The Beetle was a brutally-honest car, after all (Flammang 76).

Figure 2 Figure 2

Following that Beetle ad, the Truck dominated the spotlight of Volkswagen advertising for nearly two years (with, still, an endless supply of witty facts), until the Beetle took the spotlight again in April of 1961 and did not let it go through 1965. In the space of those four years, Volkswagen continued pushing different messages in Newsweek with the same honest philosophy it had already used, making such statements as "One nice thing about an air-cooled engine: you never run out of air," and asking, "Is this the reason most engines still aren't in back?" referring to a picture of a horse and buggy (27 Aug. 1962, 36-37; 19 Aug. 1963, 6-7). In the short time that Volkswagen had been advertising within the United States, the organization had created its image, announced its presence, and, like the emperor and his new clothes, showed up bare for the world to see. But drivers tended to get more than met the eye with a Volkswagen because, yes, they were ugly, but "ugly was only skin deep" (20 Jun. 1966, 3; see Figure 3), and Volkswagen was always changing what you could not see within the car in the name of quality (25 Mar. 1963, 38-39). For the first half of the 1960s, Volkswagen had crafted a campaign that painted the picture of an ugly car that ran well and that was not going to get any prettier over time (but it was not going to get any uglier, either).

Figure 3

The campaign to this point had been a huge success, as exemplified not only by sales, but also with the Beetle becoming a topic in normal conversation, even among those who did not own one: "Owning a new, shiny, unscratched VW is like having purple hair -- it’s difficult to get your friends to talk about anything else. They have all seen and laughed at the humorous VW ads on billboards and in newspapers and magazines. The strange thing is that 99% of the people that want to talk to you about your new Bug have never owned one themselves" (Volkswagen AG 53, 87; also qtd. in Schofield 13). The Beetle was becoming a household name in America, and along with the Beetle came the potential for a number of lifestyle changes. For one, the Beetle was an inexpensive car compared to the other offerings from Detroit at the time, and, as a result, it opened up the door for families to own two cars. The Beetle also allowed individuals to commute to work rather inexpensively, should they choose, thanks to the Beetle's economical reputation. The total effect of the Volkswagen Beetle on society is nearly impossible to measure, but there were more than just economic benefits.

By the mid 1960s, the VW Transporter developed into a symbol of peace and free love for the hippy crowd. That fact is notable for an organization that had earlier aimed to produce the symbol of the new socialist republic (McCormick C12). Perhaps the hippy crowd was attracted by the counter culture undertones of the Volkswagen campaign, or perhaps the Vietnam War on the horizon caused memories of World War II to fade into the background (or, perhaps the hippy crowd just had not read up on their European history before picking a car). Whatever the reason behind the development, the Volkswagen campaign had grown the brand into a symbol, and all the while, as the social environment changed around it, the advertising message remained constant.

The late 1960s brought new horses to the Volkswagen stable, and with them came unique takes on the standard Volkswagen ad format, tailored to the audience for each car. While the Beetle, Transporter, and Truck ads remained constant throughout the 1960s into the 1970s, the newcomer Karmann Ghia had a much different image to uphold. A 31 January 1966 Newsweek ad proclaimed that the Ghia was Italian-designed and represented a variation to the existing Volkswagen theme (15). It was the car that was supposed to rival the sporty offerings from Detroit -- not in terms of power, but in terms of class. The Ghia was marketed as "The Pussycat," as an alternative to Detroit's Mustang, Cougar, and Barracuda. It was also referred to as the "wild horse," "man-eating tiger," and "killer fish" in one Newsweek ad (2 May 1966, 7). The Ghia ads seemed to aim for a different type of driver, and the self-deprecating humor of many Volkswagen ads was lacking. In its place was a humor that made fun of other Volkswagens, in an attempt to make the Ghia look better. For example, in an advertisement that flaunts the Ghia's nimbleness in traffic and touts the Ghia as "King of the Jungle," the closing line of the ad states: "About the only thing it doesn't do like a VW is look like a VW. Nobody likes an ugly king." Volkswagen wanted this advertisement to make it clear that the Ghia was a Volkswagen on the inside, but something much different on the outside (17 Oct. 1966, 8B).

Other Volkswagen entries during the late 1960s used a similar approach to advertising as the Ghia, taking a small portion of the humor from the Beetle/Transporter advertisements, and then building upon that already-established pattern in ways unique to the particular vehicle. The VW Fastback, for example, was touted as having "all the beauty of the ugly one," in reference to the Beetle (28 Nov. 1966, 3). The VW Squareback was often compared to the Transporter in advertisements, as in the one that stated "It would be less than honest to call it a station wagon" because it did not hold quite as much as the Transporter (22 Nov. 1965, 1B). The entire family of Volkswagen vehicles, it seemed, all relied upon the reputation established by the Beetle nearly twenty years earlier in one form or another. This fact is perhaps best exemplified in a Newsweek advertisement in the late 1960s that featured the entire Volkswagen lineup, with a series of stories about Volkswagens that have lasted a very long time, and were still running strong. The advertisement ended with a blanket statement for all Volkswagens: "So next time you look at a Volkswagen, look at it this way: It's not the most beautiful body in the world, but it's one of the healthiest" (13 Nov. 1967, 38-39). Thus, Volkswagen closed off the 1960s, by basking in the ugly lifestyle the American public had grown to love so much.

The Progression of the Campaign: Newsweek (1970-1980)

Moving into the early 1970s, the Vietnam War was still on the mind of many Americans, the gas crisis was just over the horizon, and Volkswagens were still ugly. Not only that, but Beetle sales in America slumped from 570,000 to just under 486,000 in the years between 1970 and 1972 (Volkswagen 59). Volkswagen also found itself in hard times trying to import into the United States, due to changes in the exchange rate between Germany and the U.S., and temporary import taxes imposed by the U.S. government (Volkswagen 58-59). These troubles were not directly visible in most of the organization's ads, although a Newsweek advertisement in 1972 did feature a picture of the Beetle, stating: "Under $2,000 again. Now that the tax and money situation is back to normal, we can go back doing what we do best: Saving you money" (27). Despite Volkswagen's honesty in advertising, sales continued to slump, from 540,364 vehicles in 1973, to 238,167 vehicles in 1976 (Volkswagen AG 91). Times were rough for the company. The majority of the Volkswagen advertisements during the early 1970s continued as they had started in the 1960s, by portraying the Volkswagen lifestyle through wit and humor, with a hint of discord. A particular series of advertisements, however, took a different approach and offered the personal stories of individuals who actually owned Volkswagens. These stories ranged from long extrapolations about the joys of owning a Volkswagen to more detailed stories that showed individuals who were dissatisfied with other cars on the market and eventually “got the bug again,” returning to Volkswagen (24 Sep. 1973, 86-87). These advertisements were also some of the first to put faces with actual Volkswagen customers. But, despite this new direction in advertising, there were still plenty of Volkswagen ads being run that were identical in

format to the original ones (some actually were original ones, reprinted in color or slightly updated).

Even when the VW Dasher was added to the lineup in the mid 1970s, bringing with it a completely new advertising design that focused on full-page color photos and diagonal text, Volkswagen continued to intersperse the older ads throughout the campaign. It was as if Volkswagen wanted to attract a new crowd while still maintaining the nostalgia and wit that had become synonymous with the Volkswagen brand. Such a strategy is hardly a crime, but attempting to straddle the fence has the potential to blur boundary lines, or, in this case, to dilute the established Volkswagen lifestyle associated with the car; and without the lifestyle connection, Volkswagen would be just another brand.

Perhaps Volkswagen had this scenario in mind when they attempted to inject their mid 1970s advertisements with a touch of nostalgia, by adding the slogan "Volkswagen does it again." Whenever advertising a new model, from the Dasher to the Scirocco to the Rabbit, many times Volkswagen included the “Volkswagen does it again” slogan in the corner of the page (7 Aug. 1978, 32; 28 Aug. 1978, 27; 26 Nov. 1979, 80). It may have lacked the punch of the "Lemon." ad, and it did not quite carry the humor of some of the others as it attempted to stand on the shoulders of the campaign from the previous decade, but did it have the weight to carry Volkswagen into the future? That was the ultimate question. With the Rabbit gaining in popularity as the 1970s came to a close, and with sales on the rise yet again (even through the second oil crisis), the future was looking up for Volkswagen (Volkswagen AG 91). However, despite Volkswagen's perseverance in growing through the problems that arose in the 1970s, the organization was never able to recapture the spirit of the Volkswagen lifestyle that had been nurtured by Helmut Krone and Julian Koenig at Doyle DDB; at least, not by the beginning of the 1980s.

Conclusion

The Volkswagen lifestyle was the result of the combination of a three main factors. The first factor is the peculiarity of the cars. Without its unique body style, rear engine, and reputation for fuel economy, the Beetle would have lacked an essential ingredient to its success: instant recognizability. Looks may not have been the sole factor in the car's success (the AMC Gremlin looked weird too, but nobody talks about those anymore), but they enabled Americans to identify the cars on the spot, which may be why "everyone [has] an opinion about the Beetle" (Schofield 13).

The second factor is the corporate philosophy. Heinrich Nordhoff's philosophy of providing an “honest value” for consumers opened the door for Krone and Koenig to do something that had not been done before in automotive advertising: to take a risk and to communicate with customers directly and honestly.

The third and final factor is the advertising campaign itself. The DDB campaign used Volkswagen's unique product, adapted the message to Volkswagen's unique business philosophy, and then translated those into an almost tangible lifestyle. With a touch of wit, humor, and even discord, Krone and Koenig added depth to the Volkswagen brand and created a campaign that provided the foundation for all other Volkswagen campaigns to date. Current studies on viral marketing could learn a lesson or two from the processes implemented within the Volkswagen campaign, as the Beetle "fever" that started up so long ago still has embers in today's society, though the Beetles get older every year. Luckily, there's a saying that follows most Volkswagen enthusiasts: "Old Volkswagens never die, they just become playthings" (Schofield 5). It sounds like this virus is going to be around for a while.

Perhaps the most obvious limitation to this research was the reliance upon Newsweek magazine as the primary source for information. A more thorough analysis could have been performed through researching a variety of publications, representative of a diverse group of demographic backgrounds, in order to see how Volkswagen targeted specific groups and to draw comparisons between what Volkswagen communicated to each individual group.

Another limitation to this study is its time frame. While this paper attempted to study the most applicable period for the U.S. advertising campaign, there are undoubtedly international issues that influenced the decisions Volkswagen made throughout its formative years. Future studies could consider studying this same topic from a German perspective. Other possible suggestions for additional research include a study of the American automobile manufacturers and how they reacted to the Volkswagen Beetle, both through advertising and through dialogue with the media. Furthermore, an examination of how the Volkswagen brand continued to develop past the 1980s could yield interesting insight, as the Volkswagen GTI advertising campaign during the early 2000s continued Volkswagen's attempt to capture new, younger audiences, while simultaneously providing nostalgia for the old. A comparison between the advertising campaign Volkswagen sponsored in Europe and the U.S campaign would also provide insight into what messages Volkswagen was sending to its potential customers internationally.

Works Cited

Challis, Clive. Helmut Krone. The book. Graphic Design and Art Direction (concept, form and meaning) after advertising’s Creative Revolution. The Cambridge Enchorial Press, 2005.

Flammang, James M. Volkswagen: Beetles, Buses & Beyond. Krause Publications, 1996.

"German Mirages." New York Times, 20 Nov. 1940, p. 20.

Jewell, Derek. Man & Motor: The 20th Century Love Affair. Walker and Co., 1967.

McCormick, Anne O'Hare. "The First Home Thrust at the American Standard." New York Times, 11 Aug. 1941, p. C14.

Moore Robert, E. "From genericide to viral marketing: on 'brand.'" Language & Communication, vol. 23, 2003, pp. 331-357.

Nelson, Walter Henry. Small Wonder: The Amazing Story of the Volkswagen.

Little Brown & Co, 1970.

Rayport, Jeffrey. "The Virus of Marketing." Fastcompany.com,

www.fastcompany.com/27701/virus-marketing.

“Sales up Sharply for Foreign Cars.” New York Times, 14 April 1957, p. WT11.

Schofield, Miles. The Complete Volkswagen Book - No. 2. Peterson Publications, 1971.

Spielvogel, Carl. “It’s the Difference That Sells the Volkswagen.” New York Times, 20 Oct. 1956, p. 12-13.

Volkswagen. Advertisement. Newsweek 28 Dec. 1959: 70.

---. 4 Apr. 1960: 10-11.

---. 11 Apr. 1960: 13.

---. 29 Aug. 1960: 50.

---. 26 Dec. 1960: 62.

---. 27 Aug. 1962: 36-37.

---. 25 Mar. 1963: 38-39.

---. 19 Aug. 1963: 6-7.

---. 22 Nov. 1965: 1B.

---. 31 Jan. 1966: 15.

---. 2 May 1966: 7.

---. 20 Jun. 1966: 3.

---. 17 Oct. 1966: 8B.

---. 28 Nov. 1966: 3.

---. 13 Nov. 1967: 38-39.

---. 29 Mar. 1971: 59.

---. 24 Jan. 1972: 27.

---. 24 Sep. 1973: 86-87.

---. 7 Aug. 1978: 32.

---. 28 Aug. 1978: 27.

---. 26 Nov. 1979: 80.

Volkswagen AG Corporate History Department. Volkswagen Chronicle Volume 7: Historical Notes, A Series of Publications from the Volkswagen AG, Corporate History Department. Werbedruck Lönneker, Stadtoldendorf, 2003.

“Volkswagen Bares Its Finances; Cash Reserves at $34,720,000.” New York Times, 24Dec.1955, p. 20. |

Figure 1

Figure 1 Figure 2

Figure 2