I took the subway from Harlem and joined the Bronx sidewalk group "as though in quest of a [cleaning] job and saw these twenty or more unfortunate women who were partly clothed, some with [...] warped women's shoes, [...] the cast-offs of some [...] 'Madam.'"

--Vivian Morris, "Bronx Slave Market," December 6, 1938

At City Hall [...] nothing like this caint even scrub the marble floors or polish the brass [...] folks in this [Harlem] park caint even get on relief.

--Ralph Ellison, "Colonial Park," June 6, 1939

Do you remember the picket line

And the sting of the driving snow?

When you marched in the cold

by the Chelsea docks

Not very long ago? [...]

The [Harlem] strikers black, and

the [other] strikers white,

all shared and shared alike.

--Saul Levitt, "New York Watershore Stories: Poems

and Stories by Seamen," November 14, 1938

For the roughly twenty percent comprising the nation's jobless people and the countless millions whose lives were also governed by poverty, 1938 was still the Great Depression. The official New Deal truth, though, was of a strong recovery. The American Life History Manuscript Project (ALHMP), largely focused on 1938 and 1939, remains a huge oral history of the average American during that period; it eventually numbered more than 2900 records ("About this Collection").1 In a neat fit, an army of white-collar work reliefers translated into print people's descriptions of an astonishing range of jobs. From the outset, the originators acknowledged that working people left few records of their life stories. Viewed from our time, this was a pioneer initiative.

Ideologically, however, this American orality was circumscribed by resilient individuality. As much myth as reality, observed one student of the Federal Writer's Project (FWP), the field staff was encouraged to choose the voice of "romantic nationalism" (Hirsch 4). Thus, the overwhelmingly white cadre earned their pay with narratives of "resourceful, unembittered men and women" (Stott 204). The sanitizing insistence was that they coped well with the "vicissitudes of daily living" ("About this Collection"). While there were references to the personal misfortunes wrought by droughts, foreclosures, and unemployment, chosen speakers exhibited optimism. Either invisible or in stray texts were poor whites denied relief by the New Deal. Farmed out to separate projects were American "ethnics," usually of Mediterranean and East European origin.2

The originators of this democratic mosaic could not, though, bypass African Americans. However, its mediated self-portraits of the largest and poorest minority in the country were documentary failures. As second-class citizens at best, these forgotten people struggled with joblessness that was twice to three times as much as whites' even in the recovery years. When an African-American, working class person was a source, it was the product of predominantly white-on-black interviews that were likely intimidating. African Americans were only 2% of all FWP writers; whites controlled the outcomes (Griswold 108n18). This "bottom dog" population was constructed as a largely rural cast of low-wage laborers on the other side of the tracks. Among them were loquacious post-slavery genealogists; compliant sharecroppers, submissive laundrywomen heads of families; song-and-dance people, and sage – or occasionally resentful – midwives who attended to women of their own race. In parallel choices blacks in segregated industries often rationalized discriminatory practices. The most disingenuous explanation of skilled-black absence in one published Writers' Project volume listed four hundred local occupations. In choosing representative ones, the editor defended the exclusion of skilled blacks: there was no room to include them (Couch xii).3

However reluctant most labor historians have been to take on the mammoth repository as fragmentary, ephemeral, or unreliable, scholars of working-class studies have long explained that working people leave few records.4 Depending on those who speak for instead of with does not do justice to the first person accounts at the heart of the ALHMP. Accordingly, I devised a method to unearth the missing texts. After a number of months sampling or skimming one hundred selections, I based my scrutiny on about fifty selections, enough to determine the substance, style, and subtexts of overwhelmingly white-on-black interchanges. Black-on-black pieces were quite rare, except for the family histories and folk stories of rural genealogists. My explications of this print-mediated black orality were helped by the Library of Congress finding aid. The aid cross-lists the twenty-four surveyed states with cities, job types, key words, and interviewers. (Names of interviewees were typically absent or pseudonymous.) Astonishingly sparse were the hits generated by "Harlem," "Negro," "riot," "colored people," and a small number of others.5

After some months, I discovered that only a tiny pool of East Coast employees redressed the balance. Eventually, it became clear that a true resistance to entrenched dehumanization only emerged among a tiny pool of black and white staffers.6 All lived and worked in Harlem, New York City's principle black district: Vivian Morris, Ralph Ellison, and Saul Levitt.7 I term them the "Harlem Three." Vivian Morris was an African-American labor advocate who exposed the double victimization of poor black women: the shameful practices of evangelical scammers and white employers alike. One of the few to quote domestic and steam laundry narratives, she also tapped activist members of the new mass industrial. In a related way, the future novelist Ralph Ellison (1914-94) found a populace in need of a witness or storyteller in the countless men on his neighborhood street corners. Ellison's close friend on the ALHMP, a CPUSA member in a Jewish left tradition, Saul Levitt (1911-77), repurposed a union magazine to fight one of the most bigoted occupations in the United States, that of the Merchant Marine.

Historiographically there is a crisis of interpretation regarding the program in general and the topic studied below in particular. Ann Banks, reading through thousands of pre-website pieces in hard copy, produced a seminal introduction to her First-Person America.8 More common was that even transient references to the ALHMP disappear in discussions of the Federal Writers' Project.9 In commenting on how the trio mined "proletarian" New York City, explicators erase the social-historical importance of laboring people's own voices.

Characterizing Ellison's own part in enabling such speak-outs are allusions or stray phrases. Otherwise, there is an ambiguous reference to his Harlem rovings in the classic study by Arnold Rampersad, Ralph Ellison: A Biography. Except for a preface defining Ellison's interactions with Harlemites for the FWP (Bascom), nothing exists on his body of ALHMP quoted texts nor his relationship to the other key Harlem interviewers. Morris's contribution, as we shall see below, remains unexamined. Finally, in Alan Wald's seminal treatment of the American left of the 1930s, Levitt receives a few sentences as a Writers' Project collector of tales.10

My study of the "Harlem Three," in contrast, begins a conversation on the trio's collaborations with everyday Harlemites to resist widespread assumptions about blackness as inferiority. In the framing strategies, the triad devised for ghetto-based counternarratives, the three enabled the loquacious speakers' "creative constructions" (Hirsch 149).11 Working in each document as shared authorities (Frisch 17), each questioner and responder helped produce a subversive mini-archive. In a myriad of ways, I contend, the texts under discussion were particularly resonant in rejecting America's normative whiteness. To understand how gender met race in the construction of blackness, we turn first to the domestic servitude of Harlem's day cleaners.

From Harlem and Back:

Vivian Morris's Undercover Journalism

and the Laundress's Narrative

Vivian Morris was the most effective participant-observer to point out the gaps and invisibilities in the construction of blackness. Almost alone of her peers, she heard about the double burden of working women, who were both exploited by white employers and unable to forge a politics of solidarity with black working men.

Morris remains, however, enigmatic. Modern critics characterize her as a "shadowy presence [...] prolific but obscure" (Bascom 17). Others simply withhold information available to them: her name, Harlem address, and journalistic fervor. Instead her identity is that of a Works Progress Administration writer (Mohun 239). Following the Harlem-located Negro Studies Unit's (NSU) gender bias, less important staffers were women. They were not even told the title of the proposed book, The Negro in Harlem (Tarry x–xiii). (Ellison, already known, had no such difficulties.) Nevertheless, this very anonymity helped her to fade into the world of African-American women's work across the city. Under the rule that African Americans must be assigned to projects about their own race, she at first earned a paycheck in the NSU, one of the few experiments with historicizing the contributions of blacks. They had no choice of topics and were not asked about their own expertise in Harlem work worlds. Morris was not dispassionate; for the most part, her own observations of women's sweated labor observations were dramatic. Not so in "A Brief History of the Cooper School" and similar federally funded sites ("History of Harlem Art Center"). Still, the NSU tribune Sterling Brown interpreted the projected volume as a "portrait of the Negroes as Americans [and] their participation in [...] the fabric of American culture" (qtd. in Dolinar xiii).

Morris's vision could not have been more oppositional. Rewriting Brown's NSU race-based certainty and redirecting attention from the implicitly masculine, she crafted a centrifugal approach, moving in and out of Harlem. For months, she moved up and down the streets and avenues in the twenty blocks in which ghetto women returned from "whites" dominion.

Widening the forays, she recorded the hardscrabble lives of workers on the Middle West Side and up to the South Bronx. To anchor her citywide mini archive, she experimented with a narratology of poor women's manipulation, from the corrupt storefront preachers to the "slaves" of domestic service to the small number of the women who stood up for their legal rights.

This was not a teleology in the strict sense, as vocal evidence could only be collected as the occasion presented itself. But depending on the speaker, the metanarrative of swindling shifted, as in her newswoman's essay on Father Divine. Assuming the adoring voice of a scammer's congregation, she explained: "He was the Disciple of God [...] [who] rides in a big special built deluxe Duesenberg sedan with a throne in the center, for 'Father' to sit on" ("Negro Cults in Harlem").12 Not to be outdone in profits was "Mother Horn." Despite her "fishmonger's voice," she claimed a mystic power that even turned the crippled into those who "walked away healed" ("God was Happy – Mother Horn").

She saved her most vivid contempt for those white wives of prosperous businessmen. These matrons scammed in a more systemic manner, procuring "bargain women" and saving themselves large amounts of money by pitting these needy people against each other – an old labor-boss plot and one, we shall see, also deplored in Morris's colleague Saul Levitt's observations on men's job difficulties.

As described by an important Harlem journalist, Marvel Cooke, the women waited "in front of Woolworth's [Store] for housewives to buy their strength and energy for an hour, two hours, or even for a day at the munificent rate of fifteen, twenty, twenty-five, or, if luck with them, thirty cents an hour" (qtd. in Harris 91). Such were the power relations in the "Bronx Slave Market," the subjects of her morning observations, and the afternoon's "Price War in the Bronx Market." No enlightened New Yorker doubted these were throwback to a "house slave" on the plantation. Important newswomen and even the usually oblivious New York Times deplored the institution. Known to civic pillars and federal employees in the city alike, the peonage mart was synonymous with many such venues in the city. Indeed, New York's most important black newspaper provided a 1936 headline: "Bronx Evils" would continue without intervention from established labor unions ("Domestics Plan to Form Unions" 13).

Even though the practice dated from the onset of the Depression, Morris's class-passing arrival in the South Bronx in 1938 also addressed the invisibility of this in the ALHMP. Like many of her sister journalists in Harlem, Morris practiced deceptive journalism to penetrate the cowed line of day workers as they waited to be looked over. (The myth was that the mistresses even looked at teeth.) Morris quietly joined this forced parade on a bitter cold day after Thanksgiving. Just a few days later, she wrote: "Several stores surround this neighborhood slave market, mainly on the South side of 5 and 10 cents stores, where the Madams shop for domestic necessities etc., including the slave girls and women" ("Bronx Slave Market"). In this fraught atmosphere, female bossism dictated silence on the line, a sweatshop practice dating from the "dark-hued" oppression of East Europeans and Italians on the Lower East Side. The policy succeeded in preventing any esprit de corps. Morris's incognito dress reinforced her blackness in participant observation. Identifying with their white aggressors, some pathetic women bragged about their "madams" who had more money than other women.

Morris transforms her creative listening into a true conversational narrative when a few courageous ones dared describe their peonage. There are a number of key speeches in which Morris's upper and lower case amply convey emphasis: "Ah hates the [white] people ah Works for. Dey's mean, 'ceitful, an' ain' [...] Hones'. But whut ah'm gonna do? I got to live – got to hab a place to steh – 'dough my lan'lady seys ah gotta bring huh sumf'n" ("Bronx Slave Market"). However limited her use of "uneducated" speech, Morris gives the stage to an outburst with all the elements of a performance: conflict, expressiveness, and verisimilitude. In this style, she went against the FWP grain, for, complicating attempts at a sustained monologue, the FWP – with unintended condescension – urged employees to make "the inarticulate articulate" (qtd. in Lieberman 34). Perhaps in a sign of reluctance, whether conscious or not, to listen to authentic workers, the FWP provided no tape recorders. Outside New York and other cities, whites' rural twang, however, was sometimes acceptable; black vernacular was not ("Negro Dialect Suggestions").13

Realpolitik also militated against it. In the pressure to earn money and hand in assignments quickly, Morris bypassed colloquial expressions. But the default literacy she presented in her string of interviews on light industry was also symbolic of a shift in job possibilities: language as a form of upward mobility. In "Laundry Workers," though again costumed, she showcases stark differences from the slave mart sketches. She has no reticence about moving past the foreman by showing a CIO card (although it is a mystery where she has obtained it). The ironers she visits are similarly open in affiliation. Under the umbrella of the CIO, their union is the Laundry Workers Union (LWU), the first such union in New York City and one of the largest in the United States. But in the fragmentary history of black women's progress, liberty is elusive. Despite their union dues, there was no help for the LWU to achieve collective bargaining.

Neither secrecy about her role nor ongoing repression characterize Morris's most noted sketch, "Negro Laundry Workers [interview with Evelyn Macon]." In it, again on the move, Morris has returned to Harlem for a meeting with the de facto shop steward of what is described as that of the “West End Laundry.” Morris is not charting a failure in an exhausted subway journey back home. Rather, the CIO fuels a meeting at its site of political strategy and job placement: the Harlem Labor Center's LWU Local, on 125th Street, the main thoroughfare.

Even before the event, Macon rules her narrative rather than engaging in conversation framed by the questioner. She is unafraid to use her real name, unlike those like "Rose Reed" ("Domestic Workers Union") and "Minnie Marshall" ("Bronx Slave Market"), fearful of exposure by white overseers. She dictates the month, day, and time of meeting. From her bully pulpit, Macon has set the agenda, and Morris herself could be a face in a rally crowd for all the attention directed at her.

"Negro Laundry Workers" is less a typed-up monologue than a seasoned organizer's playbook for closing down a shop. Having stage managed her own encounter, the speaker succinctly instructs Morris in work floor organizing. She begins with a kind of homage to her sister toilers: "Slavery is the only word that could describe the conditions under which we worked. [...] speed up, speed up, eating lunch on the fly, perspiration dripping from every pore, for almost ten hours per day" ("Negro Laundry Workers"). Instead of Morris's usual "they" or "I," Macon is a part of the "we" who take over the shop. She has no fear of censors of the "sordid" (Couch xii). She speaks of odor, bodies, unsanitary food.

Again unmediated by Morris, Macon turns to her labor-feminist declaration. Just as time stood still in the pre-union period, it speeds up in the rebel one. Enter an undercover CIO organizer, "Bruiser." Defying the rules of the shop, he leads by example and walks out. His well-rehearsed act rouses the women.

But in Macon's telling, a black man, however empowering, is a bridge. Once at his behest, most of the shop attends a CIO meeting the night after they instantly become experts in picketing. Just as swiftly, they "throw a line around the place." Catching up for their sweated time, and without need of Bruiser, they push the manager to capitulate. In familiar white boss fashion, he promises a company union with the same benefits. They refuse. In almost a fantasy of triumph, they turn him "frantic." He "called us back to work at union hours, union wages, and better conditions" ("Negro Laundry Workers").

It should be noted that Morris’s arrangements, like those of Ellison and Levitt, are not teleological: interviews are out of chronological order and can be read in several ways. But however her corpus of selections is read, the battle between so-called subaltern women and their bosses has been joined. While no statistician she might have further researched the flowering of the city’s CIO laundry union and its appeal to 30,000 largely minority laundry workers.14 As further evidence of the multiple and contradictory meanings of the Harlem manuscripts, however, no such proactivity appears in Ellison’s writeups of Harlem masculinity.

Ralph Ellison and the Harlem Unemployment Monologues

Although they were hunter-gatherers of inner-city orality, Morris and Ellison saw Harlem through the lens of gender. They walked past the same spiritualist churches of Daddy Grace and the tired women en route to subpar jobs. They heard the back and forth of male urban sociability and checked in at the Schomburg Library NSU headquarters on Lenox Avenue and 135th Street. For Morris, the brief transit was uncharacteristic, a small part of her travels to women's jobs in the city. In contrast, Ellison roved the streets centripetally, which was also a gendered mapping: women went to work; Ellison's jobless men stayed in the neighborhood.15

In his most fully realized pieces, the men, like Ellison himself, thus remained close to home. These veteran talkers were single men who did not mention families to feed (or gave them short shrift). Their home and work sites were replaced by the street, the parks, and the taverns, each a few blocks away. Though disgruntled, these orators did not seek change. For Ellison, this familiar radius of fifteen blocks provided enough street theater to provide theatrical display. Thus, their job-seeking inertia was in counterpoint to their energetic orality. From young to old, they were "taking it out in talk" (Drake and Cayton 718). Showing off, they were comfortable in a verbosity that entertained.

One of many such speakers is the jazzman "Jim Barber" ("City Street"), whose earnings were contingent on white customers' contributions of "beatup change." Seething at a recent incident, he aired his grievances to sympathetic listeners like Ellison. The interviewer himself well knew the hand-to-mouth contingency, as he had been a jazz musician in Chicago and had his own hard times on his first day in New York. He was also familiar with the condescending white customers such as those Barber decried.

Barber turns his outrage into a one-man show. Recounting his humiliation, he seethes at the memory of these "bums" who pretended to offer him four dollars, which was a considerable sum at a time when, if employed at all, African-American workmen, most with families to support, earned less than seven dollars a week (Ottley and Weatherby 284). As with Ellison's other memorable personae, Barber performs his own ad hoc script. The musician's voice rises as he recounts that the money offer was a ruse. As the men escalate their insults about him, Barber realizes these jokers saw him as the Comic Black, ignorant and unwitting. Upon hearing a few bars of music, they insult Barber: "you stink." Perhaps, too, that is a double entendre, given white clichés about African-American cleanliness. But on his home turf, the incensed man has no fear of replying: "goddamn it," each one of you is a "motherfriger," a "sonofabitch," and a "crummy bastard" ("City Street"). Moving from verbal to the physical thus fashions a persona of the "Dangerous Black," as he pretends to have a gun in his pocket.

If he scared the men that night, in the next few days he expanded his condemnation to American whiteness. This time he lumps his harassers with what Southern blacks termed "white trash." He erases the fact that his hecklers had enough money for entertainment. Instead, each one is a just a poor white: "He aint got nothing. He cant get nothing. And he thinks cause hes white hes got to impress you cause you black." While in this pint, Barber simply echoes a familiar ghetto prejudice, he expresses similar hatred of those at the other end of the financial spectrum, Harlem's Jewish businessmen. They were denigrated as, according to Leon Fink, "in between whites" (qtd. in Barrett 52), who also debased blacks by cheating them of jobs.

The musician's fury mounts as he uses the canard that blacks were rightly treated better than Jews in wartime Germany. For once shifting from his own grievances to that of his community, he exclaims: "Hitlers gonna reach [New York] in a few months and grab and then thingsll start. All the white folks be killing [...] one another. And I hope they do a good job!" ("City Street").16

Political predictions cede to religious ones in "Colonial Park." On one occasion, Ellison sat down with an elderly Virginia veteran of the Great Migration. With white soldiers away in World War I, he had joined the unprecedented human flow from the South. Yet the advancement was short-lived. His only allusion to the migration and its unrealized hopes was the succinct statement that he "was 25 years in the neighborhood." Such reticence about the struggle for survival – even in a job like Barber's contingent one – is becoming to this Harlem Tiresias.

In titling the interchange "Colonial Park," Ellison was aware of its irony of the name.17 On his first night in the city, he slept on a bench there (Taylor 94). The location was also part of a de facto colony of the white city, sucking out tenement rent and withholding blacks' jobs to pay it. Early on, the wizened talker offers superficial sympathy with an opening remark on the loss of two white-manned submarines in pre-wartime exercises.18 He recalls the same dictate on the Titanic in 1912, two years after he settled in Harlem: "Nothing the color of this could git on the boat. Naw suh! Didn't want nothing look like me on it. [...] They didn't want nothing look like this." The use of the third person is an initial identification with the adversary. As his voice rises and falls, he sees justice in the sinking: "Them what take advantage of the color of skin got to come by God. They gonna pay." The prophecy about the destruction of whites, whether Barber's political one or the elderly man's religious one, was not the only way that men negotiated their marginal economic status. Alienation can also have an impact, as this disappointed man reveals.

Ellison's interviews elide the difference between hand-to-mouth street talkers and those ensconced in local taverns. "Harlem – Eddie's Bar" was the result of Ellison's barroom studies. Here he disappears into the drinkers' background and overheard anecdotes and capsule life vitas. One day, he moves quietly to the back room, beckoned by a solitary man who sits there by virtue of disposable income. Evidently welcomed by this loner brooding in privacy, he becomes a sounding board again. Though the unnamed speaker is a middle-aged cynic, unlike the young man and the old man, he has held down some job. His financial past is mysterious though. This omission is telling; the very man saved from the troubles of Barber and the elderly bench occupant is the most disappointed of all. His very ability to sit in his own section of Eddie's embitters as much as it enables. As he looks outside, he sees only living street proof of inner-city pathology – thieves, pimps, prostitutes, numbers runners. He is liberal with his condemnations: of the Mafia's citywide illegality, of the local blacks for doing their bidding, and of the poor for remaining so. He registers his contempt obsessively in the mantra, "Ahm in Harlem but Harlem ain't in me [...] or I'd a been dead a long time ago." In this refrain, the talker reveals a vulnerable side. He argues that he "drinks to think" – a common defense. Moreover, given his insulation from white mistreatment, he protests too much. The reader is left to speculate what is in him. The likely answer is that he is an isolato. No less than Barber and the elderly Virginia migrant, he shuns involvement. Beneath his moralizing is another Harlemite whose only words are those of defeat.

In a review of a political biography of Ellison, the socialist journal Solidarity contends that his loquacity revealed "class-conscious vernacular critiques of racism" that tallied with Ellison's own leftist views on black self-determination (Mills). Certainly, the subtext of Ellison's after-hours writing underscores the need for Harlem manhood. But at the core, whether or not the speakers know their wall of words cannot protect them, the key trope is of impotent anger. To replace that orality of alienation with one of direct action, we must turn to the texts of Ellison's friend Saul Levitt.

Saul Levitt, Voices of Brotherhood,

and the Harlem Seaman's Strike

Ralph Ellison met Levitt in 1938. They participated in an immediate "exchange of subjectivities" (Trachtenberg 273). They even resided in West 150th Street apartment buildings next door to each other and, repeating the act in early 1939, relocated elsewhere in Harlem. Ellison later remembered that, after hours, they visited landmarks as they debated "political solutions to society's problems" (qtd. in Mangione 186). Associating historically oppressed Jews and African Americans, Ellison declared, "The only difference between the North and the South [...] is [in the North] they're beating the Jews as well as the Negroes" (qtd. in Foley 330). Supporting that view was Ellison's "Anti-Semitism among Negroes," which appeared in the April 1939 issue of the Jewish People's Voice (Foley 32).

Levitt was no stranger to anti-Semitism directed at "Commie Jews" like himself.19 His focus, however, whether in the Communist Party literary organ, New Masses ("The Tall, Dark Man"), or in his selections from writings of radicalized black seamen, was Jim Crow. Harlem was a place of intense political activity for black Party members defending workplace parity.

For this vocality of dissent, he chose a worksite narrative countering that of the Merchant Marines' territorial hatred of the new "red and black" incursion. Employing his whiteness, Levitt penetrated waterfront circles. He was immediately complimented on his skin color: "[We] can see you're an American" ("Marine Workers"). His new friends sermonized: "Bolshies [...] wreck every goddamn union in the country," complained a mariner deploring such illegality ("Marine Workers"). These lily-whites would definitely have approved of the sheriff who broke up a Gulf Coast union local meeting. Before beating up a member of "the CIO-Communist Party" (Nelson 32), he warned the man that he "had no business telling the niggers about their rights" (Nelson 33).

Such fears were realized in Harlem as in other seaport cities with sizable minorities. Blacks under the New Deal who were qualified could now man the convoys, cargo transports, tankers, and passenger lines of commercial shipping. As early as 1935, the Roosevelt administration’s Wagner Act legalized collective bargaining with its concomitant right to nonviolent strikes if employers refused to negotiate. The biracialism inscribed in the legislation, not surprisingly, was constantly tested.20

Levitt found the front line for this counterassault by anthologizing the Pilot, which, before the war, was a progressive journal of the National Maritime Union (NMU). A weekly begun in 1938, the paper was disseminated in venues from hiring halls to workers' locals to uptown strategy meetings. Levitt's decision also enabled him to thumb his nose at the ALHMP.21 The program ideally saw published versions of the more democratic interviews. In Toby Higbie's view, such publications helped define "a rich print culture that focused on issues of economic inequality" (28). Levitt reversed the process: the Pilot had already validated in print the cross-racialism tabooed in standard ALHMP writeups. Now that program's heads would read the motto already validated in Harlem journals and strikes: "Black and White! Unite and Fight!"

There were other reversals as well. One of the most relevant to the agenda of the "Harlem Three" was the eloquence with which contributors described recent struggles for agency in the Harlem Seamen's Strike of 1936-37. For one thing, the well-read authors' accounts of the strike straddled the divide between print and oral format (Adrien 105). They provided a rhetoric of brotherhood accessible to waterfront and shipboard audiences used in recitation and singalongs: Thus the refrain that Levitt reprinted in discussions of marchers as they arrived at the protest site a few blocks away from the headquarters of the NMU:

By the Chelsea docks

The strikers black and

the strikers white

All shared and shared alike. ("New York Watershore Stories")

Rather than present Pilot contributions as romanticized versions of black mariners' talk, Levitt repurposed the oratory as oppositional counternarrative. With its command of American English and repudiation of ignorant blacks, it was alternate to the condescending life histories.

On the many pages of selections, the most dramatic figure was Ferdinand Smith. Among Harlem's black communists, he was a dynamo of leadership (Naison 261). By the early CIO years, Smith had garnered the support of popular newspapers as diverse as the Amsterdam News and the sociological Opportunity: A Journal of Negro Life (Granger). Inspired by his crusading fervor, a coalition of community leaders and pastors joined what he named the Harlem Committee to Aid the Striking Seamen.

In one Pilot account, it was Smith who mapped the long march from 125th Street during the punishing winter of 1936. He and his allies engaged in what labor geographer Don Mitchell defined as "organiz[ing] the landscape": "With odds and ends of lumber, he managed to set up tables and benches – [for food]. Nobody knows where he got 'em – he managed to get a hall [near the Hudson piers] without a down payment. There was a mystery as to how it was done, but Ferdinand Smith did it [because] he went up to Harlem for support" ("Forty Fathoms," emphasis added).22 Despite the rise of working-class consciousness in the city's African-American Merchant Marine, the various national maritime federations had not yet coalesced. The strike ended with no employer concessions.

In Levitt's optimistic compilation, that was not the Pilot message. The noted sociologist and author of Home to Harlem (1928) Claude McKay reasserted the CIO-CP role in helping labor "step [...] out" in Harlem ("Labor Steps Out" 88). Ferdinand Smith himself continued to crusade, calling on the labor movement in 1940 to "protect [...] the Negro Seaman" (112-14). As integration moved slowly for merchant ships, he created a wartime journal aptly called The Voice. His reputation secure, he did not forget his Harlem following: in wartime he was called on to mediate labor disagreements (Naison 101).

However romanticized the language of the Pilot writings by ordinary seamen African Americans not only had the right to leave Harlem behind. They also joined their voices to those of their white comrades. One voice – educated and color blind – reflected many. Thus did Levitt's transgressive Pilot chorus reflect the prewar hopes of Ellison and Levitt: when the mariners came back from wartime jobs to Harlem, it should be on their terms.

Coda

Congressional attempts to end "common man" programs like the ALHMP prevailed by 1940. As with the vast majority of field staffers, Morris was not heard from again. Had the project continued, one wonders what she would have written on the NMU's female stewards ("Marine Workers Historical Collection").23

Unlike Morris, Levitt did not disappear. He graduated from City College in 1941 and was drafted as a radioman into a military that would have segregated Ellison.24 After an injury, Levitt was assigned to write patriotism into Yank, an Army journal for a white soldiery. Perhaps after the rebel years on the ALHMP he saw in the task a wry amusement.

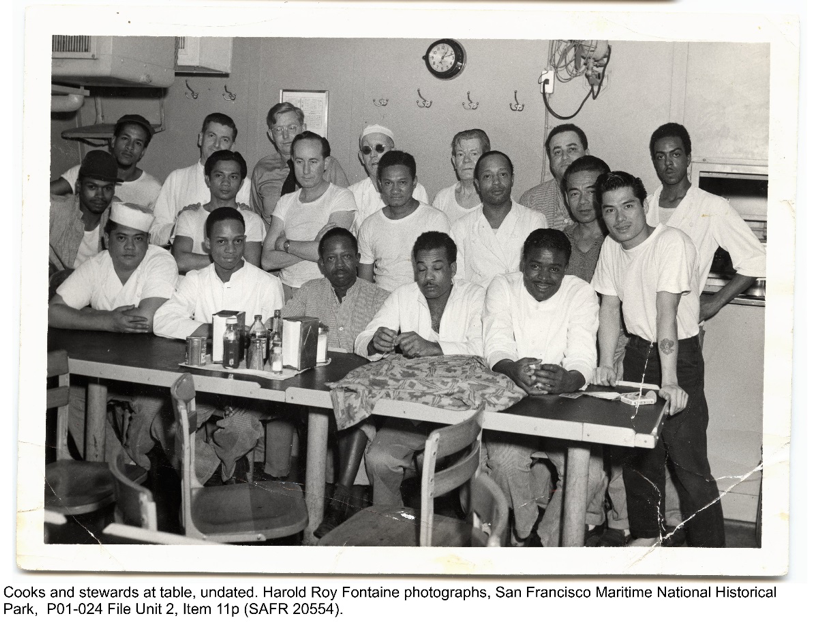

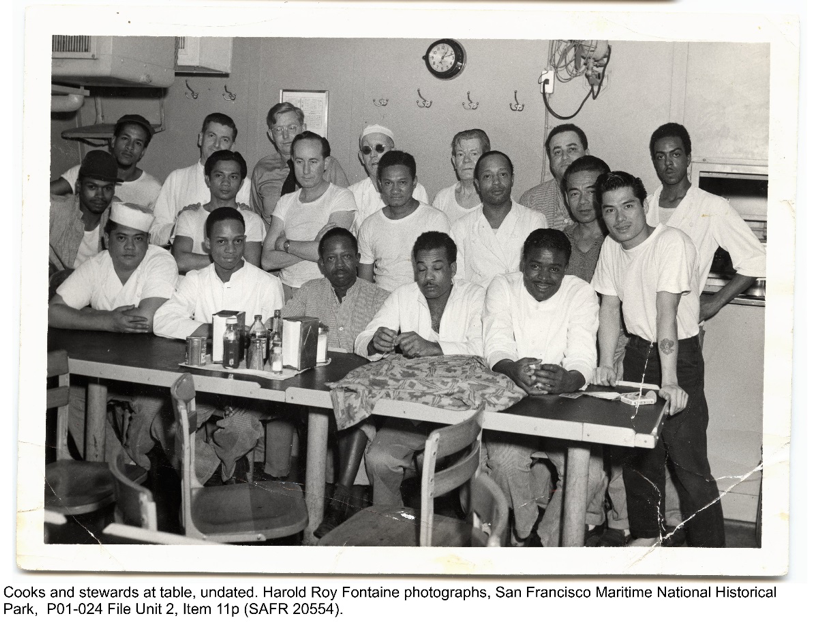

Ellison, the future literary conscience of America"s entrenched racial order, joined the Merchant Marine in 1945. Instead of acceptance, he was simply tolerated by the "patriotic" white cadre (Murray xix–xxiv). Although he sailed on "checkerboard" freights, if he knew about the Pilot, he hardly found the bi-racial brotherhood Ferdinand Smith espoused. Rather, a certain resignation characterizes the rare NMU photograph. Smiles all but vanish into shipmates' expressionlessness or anger ("Cooks and Stewards," Figure 1).25

In 1945, the same year Ellison experienced his own shipboard alienation, he began his classic Deep South-to-Harlem novel, Invisible Man.

Figure 1

Notes

1. "The American Life History Manuscript Project, 1936-1939" is the final title of the LC project though it appears to have morphed from "Folklore Division, American Life Histories, 1936-39" and other versions. I retain the updated descriptor.

Before digitization, the ALHMP was uncatalogued, it languished in the Library of Congress warehouse until the early 1990s. Although half of the collection is actually rural and pre-industrial Americana, the remaining number is daunting enough. Future articles, books, and anthologies will have difficulty with the imaginaries of class, gender, occupation, habitus, or labor mapping. At the very least, even the first stage of interpreting so vast an archive requires a command of state-of-the-art search engines, an ongoing grant, a team of researchers, and an open-ended completion date.

Given the immensity of the collection, it is understandable that no labor scholar but Ann Banks has studied the entire collection. The study took ten years. It is all the more impressive that she read the manuscript copies. See her Introduction to First-Person America (xiv). From this exhaustive roster she selected eighty interviews, stating that they were chosen for their dramatic qualities, not their typicality (xxi). Editorial information prefaces the selection and adds richness to her choices. Her introduction is excellent and covers many aspects of the project's origin, administrators, goals, and enduring value. While she does not hypothesize, she offers her own editorial arrangement of workplaces, themes, and locations that structure this content.

A representative sampling of the ALHMP appeared as reprints or in print for the first time, as in W.T. Couch's These Are Our Lives: As Told by the People and Written by Members of the Federal Writers' Project of the Works Progress Administration in North Carolina, Tennessee, and Georgia; and in Tom E. Terrill and Jerrold Hirsc'’s collection Such as Us: [The FWP's] Southern Voices of the Thirties. David A. Taylor's edited volume Soul of a People has a somewhat misleading title. It is actually a collection of the writers' self-representations and excerpts from about a score of semi-fictive accounts, some narrated by these authors. The early output of later literary notables – John Cheever, Chester Himes, and Richard Wright – outweighs attention to first-person accounts by the average people whose "soul" is the putative subject.

2. One example of the archival segregation of FWP sections is the (undigitized) mammoth "Social-Ethnic Division." While staffers within the hyphenated "American" archive did tap some non-native born, the very casting inscribed in the subjects as "in between," not fully patriotic (Cohen; see also FWP, The Italians of New York). Ironically, in an era of lingering nativism, titles and content evince the unwavering – and self-protective – patriotism of the speakers. In separate programs, state projects like the Montana FWP departed from the normative patriotism of the ALHMP and other New Deal initiatives. Staffers were Native Americans. See Morgan. Ironically, those like Dust Bowl whites – the largest group of Depression sufferers – did not generate a parallel inquiry. For self-descriptions, see McElvaine (3-32). Many modern oral histories exist, but use testimonies of people in their eighties and nineties.

3. Under the somewhat misleading term FWP Folklore Divisions, there was a number of autonomous southern oral history projects. They also highlighted the presentism of black poverty using dramatic reportage or authentic colloquial accounts, but they foreground portraits of people without rancor, as in the main collection. For instance, after decades of paltry wages, one elderly man, Clyde Fisher, stated that he had made only thirty cents an hour that year, but blamed no one as this was his "bad year") (Love and Aswell 260).

4. See Gutman, Zandy, and a host of others on the website of the Center for Working Class Studies: http://cwcs.ysu.edu.

5. Even in New York City, rarely did fieldworkers stray beyond the bounds of light irony or muted theatricality. This focus does not, of course, mean that Harlem was only a poor person's center. Well beyond the Harlem Renaissance, it was a preeminent site of black culture. Prominent writer Dorothy West's title led the way in her praise of the legendary Apollo Theater; Frank Byrd enjoyed the picturesque and the eccentric, though he smuggled in some humorous talks with "buffet flat" hostesses serving up food and commercialized sex ("Harlem Rent Parties"). Most white-on-black pieces were stereotypical. Garret Laidlaw Eskew, a white elitist on work-relief, looked from a safe distance at stevedores on the Hudson Piers. He marveled at the lone "powerful, gray-haired Negro who unlike the whites seemed to be enjoying his back-breaking work" ("Coonjine in Manhattan").

6. The obvious exceptions were their white counterparts in meatpacking Chicago, where there reigned an industrial behemoth impossible in New York. But co-authored narratives universalized egalitarianism to celebrate a new CIO multi-racial, polyethnic, and bigender factory coalition. Banks's editorial commentaries on her selected stockyards pieces and 1977-78 interviews with former project workers are invaluable (51-71, 271). But the "back of the yards" texts remain underresearched.

7. This dearth of interpretation defined my own foray into the contested terrain of the ALHMP: in the South; in "Black Belt" cities in the industrial Northeast and Midwest; in trade-specific industries employing blacks such as steel, coal, and meatpacking. After some months of winnowing the material, I realized that Harlem was the default location of ALHMP blackness.

8. On the centrality of first-person accounts, see Herbert Gutman, Janet Zandy, and others on the website of the Center for Working-Class Studies: http://cwcs.ysu.edu.

9. See, for instance, Mangione, Penkower, and Stott.

10. Information on Levitt's Depression days is sparse. A few lines appear in Wald (32, 132).

11. Not within the scope of this essay is the argument for and against testimonies as authentic utterances. For the view that staffers copied down accurately or provided the gist of the witnessing, see Terrill and Hirsch (81-89). Invaluable in this regard is Banks's 1977 interview with Ellison (237). For the opposite contention see Rapport (6-17). For the contrary contention that Ellison created the drama of pieces like "Colonial Park," see Rutkowski (42). In a sweeping assessment of later-famous authors on the FWP, Basso also argues they routinely produced their own literature out of conversational interactions (xi-xxx). Even Banks undercuts her assertions of speakers' originality when she identifies those like the Harlem Three as "Federal Writers" (51).

12. Morris and the market women were furious that he also sent out his disciples to work for less. In "Bronx Slave Market," for instance, one woman grumbles, "dem Father Divine people [...] comin' 'roun' heah s[h]outin' 'peace sister' and wukkin fo nothing.'" For other pieces critical of fast-talking preachers seeking Harlem wages and, in this case, embracing black nationalism, see her "Almost Made King."

13. For a telling contrast, see the many abbreviated quotations in southern histories like The Negro in Virginia, compiled by Workers of the Writers' Program. Paternalism ruled the largely white WPA compilers, but dialect peppered the study. One word needed no translation, as in the remark, "We got a little nigger girl that helps us." See the Couric narrative, "A Day on the Farm" (103).

14. See Geiser and Carson. While the Communist press was prone to exaggeration, in this case the figure is reasonable given the (also exaggerated) nationwide 400,000 LWU-CIO members.

15. They were not wedded to this typology, but their exchanges with African-American speakers of the opposite sex often reinforced the feminist politics of raced labor and the masculinist unemployment inactivity. See Morris, "Harlem Riot," and "Workers Alliance." Ellison addresses female subjects in "Show Girl" and "Prostitute."

16. In Barber's blinkered statement, Ellison elides the musician's language and his own customary diction. But to the informed reader, the foolishness of Barber's view is unmistakable.

17. There is another irony – Colonial Park is a balkanized site. While the men, some transplanted Southerners, avoid talk of race riots, they do not stray across the boundary separating Harlem from the wider city. Ellison knew the danger was real enough. He wrote a semi-fictional New Masses article, "Judge Lynch in New York" on a mob who chased young African-American men out of "white territory," shouting "lynch the niggers" (16). The nickname "Judge Lynch" is Father Coughlin's, a fascist radio priest with a huge following. The term also refers to Southern "hanging judges," whether under the cover of law or Klan-inspired. The Klan itself called lynching "hooded Americanism" (see Chalmers).

18. There is no better representative of ALHMP attribution problems (and mysteries) than the LC interchanges of record compared to the original – and often missing – hard copies. Clearly, more scavenger hunting in the LC Manuscripts Division is necessary. But finding and then scanning typewritten accounts to compare them with versions already online is daunting, to say the least. Understandably, no scholar has undertaken the task, and the disjunction remains between the editorial information prefacing some hand-ins and those non-prefaced online versions – in this case, the Harlem assemblage.

As it is, there are numerous unresolved contradictions. In one of the few collections of Harlem orality, despite listing his source as the "Library of Congress, Manuscript Division, WPA Writers' Project Collection, 1936-1940," Lionel Bascom prefaces "Colonial Park" with information absent from the LC site: the names of the sunken submarines; the numbers of dead; and the circumstances of the sinkings (39). Also unmentioned digitally, in "Harlem – Eddie's Bar," Bascom describes the modernism, mirrors, and a jukebox playing band music (36). In Aaron Siskind's Harlem Photographs, 1932-1940, the New York School photographer states the talker is a Pullman employee. The LC variant does not, as evidenced by DeMasi (266n17).

Some of the numerous questions are: Which is the "official" version of the enterprise? At what point did interviewers or Washington directors erase details and change titles for later scanned-in pieces? Why are some crucial interviews excluded from the website? How do the altered manuscripts interrogate the original ones? Finally, what critical apparatus should explicators use to assess the process? Multiple emails to the ALHMP archivists have provided no clarity about the differing versions, only the confusing admission that LC archivists may have retitled pieces.

19. Information on Levitt's Depression days is sparse. A few sentences appear in Wald (32, 132).

20. While the war toughened integration policies, the Pilot reflected the truth of bias. Blacks in the Merchant Marine were forced off wartime vessels carrying matériel. The NMU head, Joseph Curran, declared it was a "federal offense" (qtd. in Horne 63).

21. Any Pilot selection helped with his shortened Pilot manifesto. To evade Library of Congress notice, Levitt divided and mistitled each of two parts: "New York Watershore Stories: Work Poems and Seamen's Stories" and "Forty Fathoms."

22. Again, Smith's collaborative agenda is omitted from standard accounts as well as leftists' memoirs, including that of the veteran Communist Party mariner, Bill Bailey. Ironically, he stresses the importance of the food bank in the San Francisco arm of the strike (296).

23. A wealth of sources, including union correspondence and rank-and file newsletters, provided period material on the "working and living conditions of American merchant seamen/women." For an abstract and finding aid, see the "Descriptive Summary, Guide to the Marine Workers Historical Collection TAM 125."

24. Ironically, his manuscript "Sailor News from Spain" was marked "Woodrum Committee" in 1940. That body investigated leftist material.

25. The composition of the photo is curious too. The white cooks are segregated in the back row. Possibly, the picture was propaganda for the new union empowerment of minorities, including the lone Chinese and Filipino in the photograph.

Works Cited

NOTE on format: In listing primary sources, I have preserved the spelling and punctuation of the Library of Congress archive. In many cases, names of respondents were omitted or pseudonymous. Many addresses were also absent, except for those of the interviewers. My bibliography details the date of submission, usually within four days of the meeting.

Interviews, Monologues, and Photographs

Byrd, Frank. "Harlem Rent Parties." 22 March 1939. Library of Congress, U.S. Work Projects Administration, Federal Writers' Project, American Life Histories, 1936-39, Manuscript Division, www.loc.gov/item/wpalh001365.

Ellison, Ralph. "City Street." Interview with "Jim Barber." 14 June 1939. Front of the building at 470 W. 150th Street. New York City. Library of Congress, U.S. Work Projects Administration, Federal Writers' Project, American Life Histories, 1936-39, Manuscript Division, www.loc.gov/resource/wpalh2.22120505.

---. "Colonial Park." 6 June 1939. Colonial Park near 154th Street and Edgecombe Avenue, New York City. Library of Congress, U.S. Work Projects Administration, Federal Writers' Project, American Life Histories, 1936-39, Manuscript Division, www.loc.gov/item/wpalh001380.

---

. "Harlem—Eddie's Bar."10 May 1939. Corner of 135th Street and Lenox Avenue. New York City. Library of Congress, U.S. Work Projects Administration, Federal Writers' Project, American Life Histories, 1936-39, Manuscript Division, www.loc.gov/resource/wpalh2.21020403.

---

. "Prostitute." Harlem Photographs, 1932-1940, by Aaron Siskind. Smithsonian Institution P, 1990, pp. 65-69.

---

. "Show Girl." Harlem Photographs, 1932-1940, p. 44.

Eskew, Garnett Laidlaw. "Coonjine in Manhattan." 1939. West Street and Hudson Pier. Library of Congress, U.S. Work Projects Administration, Federal Writers' Project, American Life Histories, 1936-39, Manuscript Division, www.loc.gov/resource/wpalh0.07070413//.

Levitt, Saul. "Forty Fathoms [Pilot]." Interview with Victor Campbell. 1 December 1938. Library of Congress, U.S. Work Projects Administration, Federal Writers' Project, American Life Histories, 1936-39, Manuscript Division, www.loc.gov/item/wpalh001426.

---

. "Marine Workers." Left Rudder [Carmody]. 1 March 1939. Union headquarters at Maritime Hall, 25 Broad Street. New York City. Library of Congress, U.S. Work Projects Administration, Federal Writers' Project, American Life Histories, 1936-39, Manuscript Division, www.loc.gov/item/wpalh001430.

---

. "New York Watershore Stories: Work Poems and Seame'’s Stories [Pilot reprints]." Victor Campbell. 14 November 1938. Greek Coffeepot, 23rd St. and 7th Avenue. Library of Congress, U.S. Work Projects Administration, Federal Writers' Project, American Life Histories, 1936-39, Manuscript Division, www.loc.gov/item/wpalh001425.

Love, Lillian, and James R. Aswell. Interview with Clyde Fisher. "Didn't Keep a Penny." These Are Our Lives: As Told by the People and Written by Members of the Federal Writers' Project of the Works Progress Administration in North Carolina, Tennessee, and Georgia, edited by W. T. Couch. U of North Carolina P, 1939, pp. 253-60.

Morris, Vivian. "Bronx Slave Market." Observation: 9:40 a.m. to 1:30 p.m. 30 November 1938. 167th Street and Jerome Avenue. Library of Congress, U.S. Work Projects Administration, Federal Writers' Project, American Life Histories, 1936-39, Manuscript Division, www.loc.gov/item/wpalh001468.

---

. "Domestic Workers Union." Interview with Rose Reed, 225 West 130th Street. 2 February 1939. Library of Congress, U.S. Work Projects Administration, Federal Writers' Project, American Life Histories, 1936-39, Manuscript Division, www.loc.gov/item/wpalh001482.

---

. "God Was Happy—Mother Horn." 23 November 1938. Pentecostal Church, 129 St. and Lenox Ave. "Observation, Sunday, November 20th, 9 p.m. to 12." Library of Congress, U.S. Work Projects Administration, Federal Writers' Project, American Life Histories, 1936-39, Manuscript Division, www.loc.gov/item/wpalh001464.

---

. "Harlem Riot [1935]." 7 July 1939. [Harlem]. Library of Congress, U.S. Work Projects Administration, Federal Writers' Project, American Life Histories, 1936-39, Manuscript Division, www.loc.gov/item/wpalh001488.

---

. "Laundry Workers." 9 March 1939. West End Laundry, between 9th and 10th Avenue [Upper West Side]. Library of Congress, U.S. Work Projects Administration, Federal Writers' Project, American Life Histories, 1936-39, Manuscript Division, www.loc.gov/item/wpalh001465.

---

. "Negro Cults in Harlem." 9 January 1939. New York City. Library of Congress, U.S. Work Projects Administration, American Life Histories, 1936-39, Manuscript Division, www.loc.gov/item/wpalh001483.

---

. "Negro Laundry Workers." Interview with Evelyn Macon. 10 February 1939. United Laundry Workers Union/C.I.O. Harlem Labor Center, 312 West 125th Street. New York City. Library of Congress, U.S. Work Projects Administration, Federal Writers' Project, American Life Histories, 1936-39, Manuscript Division, www.loc.gov/item/wpalh001467.

---

. "Price War in the Bronx Slave Market." 14 December 1938. 167th Street and Jerome Avenue, Bronx. Library of Congress, U.S. Work Projects Administration, Federal Writers' Project, American Life Histories, 1936-39, Manuscript Division. www.loc.gov/item/wpalh001471.

---

. "Workers Alliance." 24 May 1939. Workers Alliance Meeting Local #30 306 Lenox Ave. Library of Congress, U.S. Work Projects Administration, Federal Writers' Project, American Life Histories, 1936-39, Manuscript Division, www.loc.gov/item/wpalh001487.

West, Dorothy. "Amateur Night [at the Apollo Theater]." 28 November 1938. Library of Congress, U.S. Work Projects Administration, Federal Writers' Project, American Life Histories, 1936-39, Manuscript Division, www.loc.gov/item/wpalh001719.

Other Interviews, Books, Articles, and Photographs

"About This Collection: American Life Histories: Manuscripts from the Federal Writers' Project, 1936 to 1939." Library of Congress, Digital Collections, www.loc.gov/collections/federal-writers-project/about-this-collection.

Adrien, Lynne M. "The World We Shall Win for Labor: Early Twentieth-Century Hobo Self-Publication." Print Culture in a Diverse America, edited by James P. Danky and Wayne A. Wiegand, U of Illinois P, 1998, pp. 101-128.

Bailey, Bill. The Kid from Hoboken. Smyrna, 1990.

Banks, Ann. First-Person America. Vintage Books, 1980.

Barrett, James R. History from the Bottom Up & the Inside Out: Ethnicity, Race, and Identity in Working-Class History. Duke UP, 2017.

Bascom, Lionel. A Renaissance in Harlem: Lost Essays of the WPA, by Ralph Ellison, Dorothy West, and Other Voices of a Generation. Amistad, 2001.

Basso, Matthew L. Men at Work: Rediscovering Depression-Era Stories from the Federal Writers' Project. U of Utah P, 2012.

Center for Working-Class Studies at Youngstown State University, cwcs.ysu.edu.

Chalmers, David. Hooded Americanism: The History of the Ku Klux Klan. U of North Carolina P, 1987.

Cohen, David Steve. America, the Dream of My Life: Selections from the Federal Writers’ Project’s New Jersey Ethnic Survey. Rutgers UP, 1990.

"Cooks and Stewards at Table." [Merchant Marines, circa 1940]. Harold Roy Fontaine Papers, P01-024. File Unit 2. Item 11P (SAFR 20554). San Francisco National Maritime Historical Park Research Center.

Cooper, Wayne F. Foreword. Home to Harlem, by Claude McKay, Northeastern UP, 1987, pp. ix–xxvi.

Couch, W. T. These Are Our Lives: As Told by the People and Written by Members of the Federal Writers' Project of the Works Progress Administration in North Carolina, Tennessee, and Georgia. U of North Carolina P, 1939.

Couric, Gertha. "A Day on the Farm." Such as Us: Southern Voices of the Thirties, edited by Tom E. Terrill and Jerrold Hirsch, U of North Carolina P, 1987, pp. 103-7.

DeMasi, Susan Rubenstein. Henry Alsberg: The Driving Force of the New Deal Federal Writers' Project. McFarland, 2015.

"Descriptive Summary: Guide to the Marine Workers Historical Collection TAM 125." The Tamiment Library and Robert F. Wagner Labor Archive. New York University, 1986.

"Domestics Plan to Form Unions: Slave Mart to Move Indoors, No Change in Bronx Evils." New York Amsterdam News, 17 October 1936, p. 13.

Dolinar, Brian. The Negro in Illinois: The WPA Papers, edited by Brian Dolinar, U of Illinois P, 2013.

Drake, St. Clair, and Horace R. Cayton. Black Metropolis: A Study of Negro Life in a Northern City. U of Chicago P, 2015.

Ellison, Ralph. “Judge Lynch in New York.” New Masses, 15 August 1939, pp. 15-16.

Federal Writers' Project. The Italians of New York: A Survey Prepared by Workers of the Federal Writers' Project, Works Progress Administration in the City of New York. Random House, 1938.

Foley, Barbara. Wrestling with the Left: The Making of Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man. Duke UP, 2010.

Frisch, Michael. A Shared Authority: Essays on the Craft and Meaning of Oral History. State U of New York P, 1990.

Geiser, Nell and Jenny Carson. “Laundry Strike: Everybody Goes Out.” People's Daily World, 6 April 2007, www.peoplesworld.org.

Granger, Lester B. "The A. F. of L., the Negro and the Seamen's Strike." Opportunity: A Journal of Black Life, 14 December 1936, pp. 378-80.

Griswold, Wendy. The Federal Writers' Project and the Casting of American Culture. U of Chicago P, 2016.

Gutman, Herbert. Work, Culture, and Society in Industrializing America: Essays in American Working-Class and Social History. Vintage, 1976.

Harris, LaShawn. "Marvel Cooke: Investigative Journalist, Communist & Black Radical Subject." Journal for the Study of Radicalism, vol. 6, no. 2, 1996, pp. 91-126.

Higbie, Tobias. Labor's Mind: A History of Working-Class Intellectual Life. U of Illinois P, 2019.

Hirsch, Jerrold. Portrait of America: A Cultural History of the Federal Writers' Program. U of North Carolina P, 2003.

Horne, Gerald. Red Seas: Ferdinand Smith and Radical Black Sailors in the United States and Jamaica. New York UP, 2005.

Lieberman, Robbie. My Song Is My Weapon: People's Songs, American Communism, and the Politics of Culture, 1930-1950. U of Illinois P, 1989.

Levitt, Saul. "The Tall, Dark Man." New Masses, 3 May 1938, p. 104.

McElvaine, Robert S. Down & Out in the Great Depression: Letters from the Forgotten Man. U of North Carolina P, 1983.

McKay, Claude. Home to Harlem. 1928. Northeastern UP, 1987.

---

. "Labor Steps Out in Harlem." Nation, vol. 145, no. 16, 1937, pp. 88-89.

Mangione, Jerre. The Dream and the Deal: The Federal Writers' Project 1935-1943. Little, Brown, 1972.

Mills, Nathaniel. “Wrestling with Ralph Ellison.” Review of Barbara Foley, “Wrestling with the Left: The Making of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man.” Solidarity 152 (May–June 2011). https://solidarity-us.org/atc/152/p3275/.

Mitchell, Don. "The Scales of Justice." Organizing the Landscape: Geographical Perspectives on Labor Unionism, edited by Andrew Herod, U of Minnesota P, 1998, pp. 159-68.

Mohun, Arwen P. Steam Laundries: Gender, Technology, and Work in the United States and Great Britain, 1880-1940. Johns Hopkins UP, 1999.

Morgan, Mindy J. "Native American Communities and the Federal Writers' Project, 1935-41." American Indian Quarterly, vol. 29, no. 1-2, 2005, pp. 56-83.

Morris, Vivian. "A Brief History of the Cooper School." 10 May 1937. Writers' Program, New York City, Negroes of New York Collection, 1936–1941, Schomburg Center for Research into Black Culture of the New York Public Library, b.3f.2r.2., digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/b8e67bb0-6c5a-0133-8734-00505686d14e.

---

. "History of Harlem Art Center." Writers' Program, New York City, Negroes of New York Collection, 1936-1941, Schomburg Center for Research into Black Culture of the New York Public Library, b.1f.2r.1, digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/f2fa66d0-5b27-0133-7fbd-00505686a51c.

Murray, Albert. "Preface." Trading Twelves: The Selected Letters of Ralph Ellison and Albert Murray, edited by J. Albert Murray and John F. Callahan, Vintage/Random House, 2000,pp. xix-xxiv.

Naison, Mark. Communists in Harlem during the Great Depression. U of Illinois P, 1983.

"Negro Dialect Suggestions (Stories of Ex-Slaves)." Slave Narratives: A Folk History of Slavery in the United States: From Interviews with Former Slaves. Administrative File, Library of Congress, Federal Writers' Project 1936-1940, Manuscript Division, lccn.loc.gov/41021619.

Nelson, Bruce. "Class and Race in the Crescent City." The CIO's Left-Led Unions, edited by Steve Rosswurm, Rutgers UP, 1992, pp. 19-45.

Ottley, Roi, and William J. Weatherby, editors. The Negro in New York, 1626–1940 [Prepared by Federal Writers' Project]. Praeger, 1967.

Penkower, Marty Noam. The Federal Writers' Project. U of Illinois P, 1977.

Rampersad, Arnold. Ralph Ellison: A Biography. Vintage, 2008.

Rapport, Leonard. "How Valid Are the Federal Writers' Project Life Stories: An Iconoclast Among the True Believers." The Oral History Review, vol. 7, 1979, pp. 6-17.

Rutkowski, Sara. Literary Legacies of the Federal Writers' Project: Voices of the Depression in the American Postwar Era. Palgrave Macmillan, 2017.

Siskind, Aaron. Harlem Photographs, 1932-1940. Smithsonian Institution P, 1990.

Smith, Ferdinand. "Protecting the Negro Seaman." Opportunity, 18 April 1940, pp. 112-14.

Stott, William R. Documentary Expression in Thirties America. Oxford UP, 1973.

Tarry, Ellen. "How the History Was Assembled: One Writer's Memories." The Negro in New York, 1626-1940 [Prepared by Federal Writers' Project], edited by Roi Ottley and William J. Weatherby, Praeger, 1967, pp. x-xiii.

Taylor, David A. Soul of a People: The Writers' Project Uncovers Depression America. John Wiley and Sons, 2009.

Terrill, Tom E., and Jerrold Hirsch, editors. Such as Us: Southern Voices of the Thirties [FWP]. U of North Carolina P, 1987.

---. "Replies to Leonard Rapport's 'How valid are the Federal Writers' Project Life Stories: An Iconoclast among the True Believers.'" The Oral History Review, vol. 8, 1980, pp. 81-89.

Trachtenberg, Alan. "Experiments in Another Country: Stephen Crane's New York City Sketches." Southern Review, vol. 10, 1974, pp. 273-86.

Wald, Alan M. Exiles from a Future Time: The Forging of the Mid-Twentieth Century Literary Left. U of North Carolina P, 2012.

Workers of the Writer's Program, compiler. The Negro in Virginia. J.F. Blair, 1994.

Zandy, Janet. Introduction. Calling Home: Working-Class Women Writers: An Anthology, edited by Janet Zandy, Rutgers UP, 2004.

|