"Cavalcade of Doom":

Wartime on the Home Front

in Cornell Woolrich's Rendezvous in Black

Americana: The Journal of American Popular Culture

(1900-present), Fall 2022, Volume 21, Issue 2

https://americanpopularculture.com/journal/articles/fall_2022/snyder.htm

University of West Georgia

|

Almost midway through Cornell Woolrich's Rendezvous in Black (1948) comes a phantasmagoric mise en scène typical of this author's thematic and stylistic bent in the wake of the Great Depression and during World War II. Bucky Paige, a recently drafted serviceman, has gone AWOL after receiving an anonymous letter warning him that he is losing his wife to another man. Evading pursuit by military police, Paige discovers that the railway coach he has boarded to make his way back home is temporarily stalled and facing "[a] train of death. A cavalcade of doom. Dozens of black cars, scores of them; shaking the rails, shaking the night, shaking the stalled day coach" (88). The passage continues:

This apocalyptic passage conveys not only Woolrich's pathologically moribund vision of human existence but also a thanatophobic extrapolation of World War II's toll in America's heartland. Hyperboles such as "[a] cavalcade of doom" and "[t]he madness of the whole universe" abound, but despite Woolrich's "bloated purple prose that thuds like overemphatic movie music," Rendezvous in Black projects an often overlooked response to what government-sponsored propagandists were touting as the "people's war" in the fight against totalitarianism overseas (O'Brien 99; Gates). In a recent book, George Hutchinson argues compellingly that subtending the 1940s, a decade when "anything seemed possible, from human extinction to the first real promise of universal peace," was "unprecedented, planetary dread. Maybe humanity would be scared into a functional unity to remake the world, or maybe everyone would die" (3). The pervasive sense of Angst among leading writers at the time was in large measure a carryover from the Great Depression.1 This claim is borne out in an article on metaphors of futility in Woolrich's work. Apropos of The Bride Wore Black (1940) and Rendezvous in Black, which bookend his "Black Series" of six novels, Karin Anette Stock observes (translated from the German by this author):

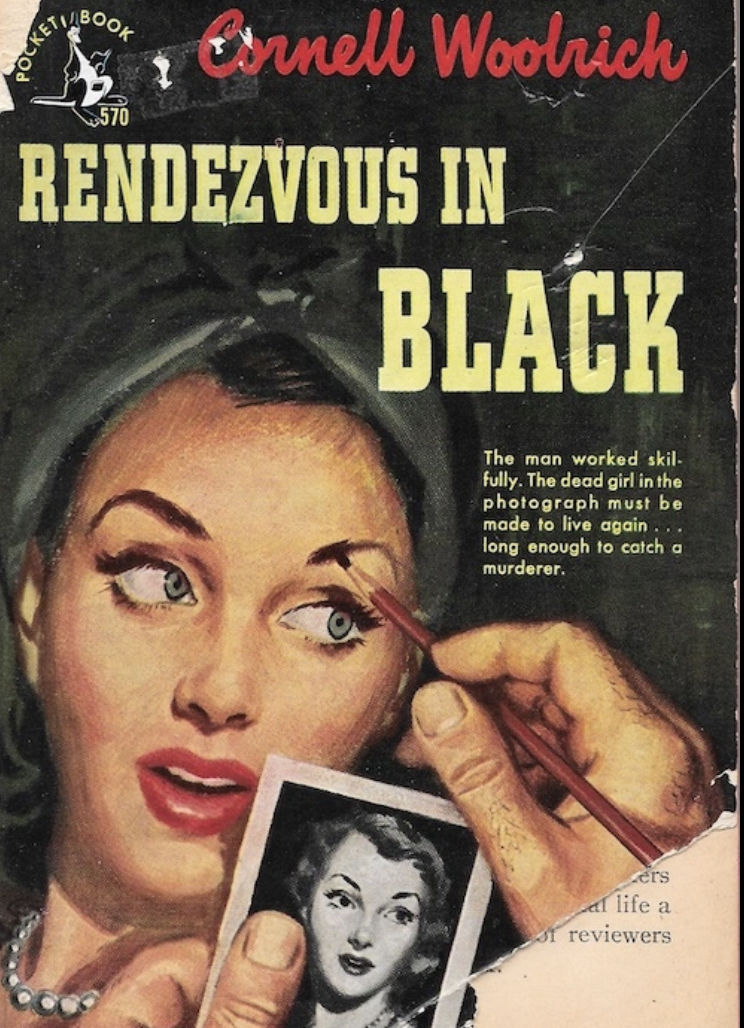

The only modification needed in this assessment is the substitution of "anti-heroes" for "heroes," since virtually none of Woolrich's characters rise to anything like exemplary stature in an age of rampant confusion, upheaval, and apprehension. The Depression's impact in this regard lingered for years beyond the nation's slow process of economic recovery. With that background in mind, any attempt to isolate the specific foci of Rendezvous in Black’s dystopianism poses a challenge because Woolrich's structural paranoia is "a response to a world where 'they' really are out to get you and paranoia is, in effect, the reality principle" (Hilfer 35). Despite this hurdle, I wish to test Geoffrey O’Brien's suggestion that although Woolrich "is an extreme case" he figures as "an interesting one because his paranoia accorded so well with the mood of the time" (100). Notes this astute critic, "His best books were written between 1940 and 1948" when "a great change came over the American consciousness...a morbid gloom which even prosperity and political hegemony could not dispel" (100). The temporal framework of Rendezvous coincides with World War II's duration and immediate aftermath. Beginning in 1941 when the protagonist's girlfriend is killed in a freak accident on 31 May, the novel's next five chapters comprise a seriatim sequence as Johnny Marr annually emerges from the shadows, always under cover of a pseudonymous identity, to avenge his loss against each of the men he holds collectively responsible for Dorothy's death.2 These "rendezvous," as Woolrich designates them, focus on the reprisals of a grief-stricken fiancé between 1942 and 1946 before a final chapter titled "Reunion" when Marr is lured to his assassination by a posse of police in 1947. So summarized, the narrative is manifestly a suspense thriller, but sparingly embedded are elements that suggest a contemporaneous doomscape inseparable from World War II and the changes it wrought on the home front. One such oblique marker is the routine of normalcy on Saturday night in small-town America when young couples gather as though by magnetic attraction on the square near Geety's Drugstore before pairing off and going to the movies. Having "first fallen in love when he was eight and she was seven" ("Sometimes," adds Woolrich, "it does happen that way" [3]), Johnny and Dorothy are marking time until they can be married in June. What is striking about their depiction is that both are wholly undifferentiated, even inane types. Dorothy "was lovely...She was everyone's first love...She was the promise made to everyone at the start, that can never quite be carried out afterward, and never is" (5).3 No less is her betrothed shorn of anything approaching individuation: "His name was Johnny Marr, and he looked like – Johnny Marr. Like his given name sounded. Like any Johnny, anywhere, any time" (4). Woolrich, in other words, is writing a parable about civilian ordinariness during wartime, but even that way of putting it is too generous because his focal personae are little more than ciphers. Dorothy then becomes the victim of a wildly improbable mishap. Approaching her usual meeting place with Johnny on the town square at a few minutes before 8:00 p.m., she is struck on the head by an empty whiskey bottle tossed over the side of a low-flying private plane transporting five fishing companions from a large city to Lake Star-of-the-Woods somewhere in the Northeast. His fiancée's death prompts Woolrich’s protagonist to undertake a war of revenge against each of the men involved in Dorothy's fate. The first two vendettas, set in 1942 and 1943, are relatively short segments devoid of historical contextualization. This absence of background may be owing to Woolrich's feeling obliged to present his novel, in light of its later twists, as a traditional whodunit. In Chapter 2, for example, he introduces police investigator MacLain Cameron, an unprepossessing detective who is guided by a tenacity for discovering the truth behind puzzling cases. Assigned to interview Graham Garrison, the first on a list of passengers that Marr finds in the files of Comet Trips for the flight in question, Cameron learns that the subject's much-loved wife Jeanette died on 31 May from tetanus as the result of her leg's grazing a nail protruding point-first from the couple's front doorjamb. Left unexplained is how the culprit who sends an unsigned note a few days later asking – "Now how do you like it, Mr. Garrison?" – could have calculated Jeanette's expiring from the wound on the first anniversary of Dorothy's death, but Woolrich does not pause over such improbabilities (27). Chapter 3 is equally bereft of a contemporaneous context, recounting the tale of Hugh Strickland, a second passenger on the fateful plane, who finds himself victimized by his socialite wife Florence for a three-year affair with one Esther Holliday. Of late, the former mistress has turned her talents to blackmail, because of which Strickland steals away from his urban mansion one night carrying a revolver in his pocket and intending to put an end to Holliday's extortion. Letting himself into her apartment with his key while Esther is ostensibly asleep, Hugh flails her viciously with a belt, only seconds later to find that she is already a corpse. Upon discovering her broken neck, an unnerved Strickland retreats to his townhouse and makes a full confession to his wife Florence, who reveals that she has known all along about his infidelity and seems to blame herself by saying, "I shouldn't have gotten so involved in my war work" (43). The reprieve, however, is short-lived. After Hugh receives a message that reads – "Now how do you like it, Mr. Strickland?" – Cameron with two associates visits him a few days later and interrogates Strickland about some mysterious scratches on the backs of his hands. Before her husband is taken into custody, Florence gloats maliciously over the revenge she has exacted for Hugh's not having killed Esther Holliday. Nine years before Peyton Place (1957), Woolrich is exploring the same erosion of mores he associates with a privileged metropolitan milieu during World War II, although again the technicalities of how Johnny Marr could have timed the outcome of this intervention are left unexplained. "The Third Rendezvous," longer than either of the first two, is notable for focusing directly on wartime's impact on the home front circa 1944. With large doses of sentimentality and stagy melodrama, Woolrich begins this installment by describing Sharon Paige's early-morning fears and apprehensions before "Mars, the god of war," demands the services of her husband Bucky as he reports for duty at his local draft board (59). From this allusion to Mars that plays off its similarity to Johnny Marr's surname, readers presumably are expected to realize that war can be waged on two fronts, foreign and domestic, simultaneously. Woolrich soon collapses these theaters of operation after Sharon bids a tearful goodbye to Bucky and accepts a job in a wartime factory where in her overalls "you can't tell I'm a woman" (67). Before long, she reluctantly agrees to do a favor for a coworker named Rusty – shades of Rosie the Riveter – by going out in the evening with Joe Morris, though Woolrich first pauses to describe a dance craze at the time: "The eighteenth century had the minuet. The nineteenth had the waltz. The nineteen forties had arrived at a state of delirium tremens, which could be turned on and off, however, without the intervention of straitjackets and attendants" (69).4 By feigning interest in her husband, Johnny Marr posing as the gentlemanly Joe Morris, who is exempt from conscription on the basis of "arrested tuberculosis," quickly ingratiates himself with the emotionally vulnerable Sharon Paige (74). He then begins sending provocative letters, always unsigned, warning Bucky that "She's going, soldier, going fast" (79). When the AWOL draftee finally arrives, pistol in hand, at the motor-court bungalow to which he has traced his wife, Paige finds her already dead before turning his gun on himself. The installment closes with Detective Cameron, who is beginning to discern a connection among the three cases of homicide to date, visiting remarried Graham Garrison in Tulsa, but little comes of their meeting except the recognition that 31 May is a significant date. A brief coda resurrects a sighting of Johnny Marr, "the phantom lover," keeping his annual vigil outside Geety's Drugstore after "[t]he war came and went" before, ritualistically, leaving flowers at Dorothy's grave site (103). Woolrich's next chapter goes further in terms of contextualization. According to the novel's internal scheme of reckoning, the chronotope is 1945, just after World War II's official end on 8 May, and pivotal to this "Fourth Rendezvous" is an image of the modern metropolis as a magnet of destruction to the innocent and unwary. In this installment, Johnny Marr, posing as sophisticated Jack Munson, lures the daughter of Richard R. Drew, another of the men he holds responsible for Dorothy's death, away from her boyfriend William Morrissey. The chapter’s first several pages reprise the narrative's opening scenario of young men awaiting their dates near a downtown clock, but thereafter it spins off in a more sinister direction as Detective Cameron resurfaces to warn Madeline Drew that she is in imminent danger from Munson. Despite the policeman's cautions and surveillance at the Drew family's seashore vacation home, an infatuated Madeline evades police cordons to rush back into Gotham to keep a prearranged date with Jack Munson on 31 May. As her "eager little roadster" hurtles "like a bullet along its concrete trajectory," intones Woolrich, "She was like a latter-day Valkyrie cresting the curved surface of the earth, into the black fastnesses of night" (136, 137). Not content with this operatic description, Woolrich adds: "The city's serrated outline crept up into the sky, in gun-metal, smoked pearl, dark-purple and charcoal-black, and she went rushing down the long descending arc of the bridge to entomb herself at its feet" (137). The set piece culminates when Cameron discovers that Marr has dispatched yet another retaliatory victim. This evocation of the postwar metropolis, transparently New York City, warrants attention in light of David Reid and Jayne L. Walker's provocative book chapter titled "Strange Pursuit: Cornell Woolrich and the Abandoned City of the Forties." Focusing on "that great anti-myth known as noir," these scholars propose that in "Woolrich's fiction, New York – any big city – is not simply noir; literally, it is mad, bad, and dangerous to know. The Depression never lifted and threatens to become eternal; the city is fallen and inescapable" (58). Such a depiction, maintain Reid and Walker, indicates "how conventional" Woolrich's "urban apocalypse really was" (58). After the "crisis of modern capitalism in the thirties," they suggest, "Woolrich's city is...animated by a Jansenist sense of evil...and ruled by a sinister demiurgic force that thwarts and deforms individual life” (69, 74). Urbanization reached its peak in the United States during the late 1940s, explains Andrew M. Shanken, after which began almost immediately an exodus of those who could afford it to planned suburbs and sprawling housing tracts, like Levittown on Long Island, as returning GI's with their Baby-Boomer families demanded safer and more comfortable living environments. This wave of a new consumer culture on the peacetime American home front, with corresponding shifts in economic investment, entailed the further neglect and deterioration of the city as it devolved into racial/ethnic ghettoes. Without explicitly addressing the dynamics of these demographic shifts, Rendezvous in Black sketches the outlines of this contemporaneous development. Woolrich's penultimate and longest chapter, set in 1946, projects the kind of romantic sentimentality that Leonard Cassuto sees as informing the hard-boiled American crime stories of an earlier decade. "The Fifth Rendezvous" also evokes the fate of a poignant, almost Edwardian innocence before the eruption of worldwide cataclysms in the form of international war. The chapter focuses on Martine Jensen, the first love of Allen Ward, before "Something happened that – came between us," and she urged him to marry someone else so that he would not "be alone any more" (151). Whatever the cause of this unconsummated romance, Allen and Martine remain deeply committed to one another over the years, despite his union of convenience with wife Louise. When Ward and Cameron visit Jensen at her well-kept home, Woolrich pulls out all the stops in sacralizing her. Surrounded by a nimbus or "sort of halo" from the sunlight pouring through a front window, she turns her face toward the visitors, at which point comes this encomium: "She was beautiful...No wonder she was the love of [Ward's] life, Cameron thought. The keynote of her beauty was youthful purity. Not lush ripeness, not exoticism; the wonder and trust of the eternal child peering through just beneath the surface of the young woman" (156). Only then does the usually observant Inspector realize that this paragon is blind. Cameron's elaborate security arrangements to protect Martine and her companion/caretaker, Mrs. Edith Bachman, are scuttled when Allen Ward, warned of Martine's peril on 31 May, turns over his share of a business to a partner and withdraws $50,000 in government bonds from a safe-deposit box for a line of credit good throughout the world. (That otherwise small detail suggests the strength of the US dollar internationally after World War II.) The couple soon absconds to San Francisco by train and thence by ship to Hawaii where they succeed in deceiving overseas officials alerted by Cameron, but after midnight on the fateful day, believing that they eluded a determined pursuer, Martine is strangled in their stateroom. What neither Jensen nor Ward had realized a few hours earlier – as a doctor explains to the latter once he has been sedated – is that as their ship sailed westward toward the International Date Line "the thirty-first lasted for forty-eight full hours" (193). By itself, this fact is little more than a clever gimmick, but as an extrapolation of Woolrich's lifelong conviction of fate's implacability, the plot point reinforces a sense of cosmic irony akin to that of Thomas Hardy. Before "The Fifth Rendezvous" ends, Woolrich appends Detective Cameron's interview with Dorothy's still-grieving mother who confesses, "I don't know what this love was. It was bigger than I could understand...I don't know how it came to them. A simple girl like my Dorothy. A plain boy like this Johnny" (198-199). The fraught reflection, of course, valorizes the purity of young love, but the concluding chapter titled "Reunion" puts a dark spin on this tale of magnetic attraction. Frustrated by their inability to apprehend Johnny Marr as a serial killer over the past five years, the police assign a young female probationer to impersonate Dorothy dressed in 1941 attire and cosmetically made up to look eactly like her. (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Front cover of mass-market Pocket Book edition published in 1949 That finale underscores the nihilism of this author's better-known productions such as The Bride Wore Black, the first novel in his "Black Series," and I Married a Dead Man – like Rendezvous published in 1948. The former is a gender-reversed tale of Julie Killeen (little subtlety in that surname) who systematically murders four of five men after the backfiring car in which they were riding careened around a corner near a church where she had just solemnized her marriage vows. Assuming that the passengers were responsible for Nick's death, his widow over the span of thirty months masquerades as a changeling who in one guise or another seeks revenge. The only difference from Johnny Marr is that she does not wait for anniversaries. To Ken Bliss during his engagement party, Julie materializes as a blonde vixen in black who engineers his fall from a seventeenth-story apartment balcony; to Mitchell (no first name given), a lonely bachelor living in a shabby hotel, she fulfills his fantasy of a woman of mystery by appearing as a glamorous redhead before poisoning him with cyanide potassium mixed in arak; to Frank Moran, the married father of a five-year-old, she impersonates his son's kindergarten teacher during his wife's absence and lures him into a cramped storage space where he suffocates; and to Ferguson (again, no first name), a successful painter, she shows up at his studio as a dark-haired model for a canvas-in-progress of Diana the huntress before impaling him with an arrow. Each of these segments of The Bride Wore Black is progressively longer, and each contains a chapter in which police detective Lew Wanger, like MacLain Cameron, tries unsuccessfully to solve the individual cases. Two years after the murder of Bliss, though, he is able to identify the fifth man in the black sedan, a prolific writer of romantic thrillers named Holmes, and take his place at the author's secluded house. Apprehending Julie Killeen, now posing as a dowdy gray-haired typist, before she can succeed in killing him, Wanger sees her metamorphose back into her actual self. While she gloats over having murdered all but one of those supposedly responsible for her husband's death, Wanger then reveals that it was not the "Friday-Night Fiends" who killed Nick Killeen but instead a former racketeer named Corey whom Julie had already encountered while stalking Bliss and Ferguson. In the second encounter, she had an opportunity to assassinate Corey with the same gun that took her husband's life, but unaware that Corey was the culprit Julie allowed him to live. With that peripeteia, the 1940 novel ends, emphasizing the nullity of human choices when balanced against a cosmic determinism. Although not part of the same series, I Married a Dead Man is a tour de force in literary noir. The work's prologue, a tone poem in prose, establishes immediately the ensuing narrative's schema of entrapment in a town that otherwise epitomizes "perfect peace and security":

The pronoun "I" in this prefatory nocturne refers to a twenty-year-old woman once known as Helen Georgesson, and "us" refers to her and new husband Bill Hazzard. The latter surname suggests the hazardry of her having assumed the identity of Patrice Hazzard after the latter's death and that of her spouse Hugh in a train wreck. Injured in the same rail disaster, the convalescent Helen finds that authorities have mistaken her for Patrice, and under that guise she arrives in Caulfield, a city of 203,000 located in a state just west of New York City. The home there of comfortably affluent parents Donald and Grace Hazzard represents a haven of security for Helen and the son to whom she gave birth prematurely during the train derailment. A sense of "belonging somewhere at last" is precious to her because, having grown up in San Francisco with a longshoreman father killed in a drunken brawl when she was ten and having migrated at age seventeen to New York where she was impregnated by a gambler who abandoned her, Helen desperately seeks safety for her newborn son (49, 107). Although terrified by the criminality of impersonating a dead woman, the protagonist nervously adjusts to her acceptance as daughter-in-law Patrice, whom the Hazzards had not met in person before Hugh's overseas marriage. The second half of I Married a Dead Man scuttles the idyll. When villainous Steve Georgesson shows up in Caulfield and proceeds to blackmail Patrice, she decides that her only recourse is to kill him with a revolver retrieved from Father Hazzard's desk. The necessity for doing so dissolves, however, when after firing an errant shot, Patrice discovers that Georgesson is already dead. Here begins a confusingly inconsistent set of plot details. Having already declared his love for the woman he knows not to be his sister-in-law, Bill Hazzard arrives on the scene and, with the nearly catatonic help of Patrice, disposes of Georgesson's corpse by dumping it atop an outbound freight-train car beyond the city limits of Caulfield. In one of those ruptures in plot coherence typical of his fiction, Woolrich confirms diegetically via a sealed letter written by Grace Hazzard before her death that Bill was the one who took his father's pistol from his desk. Despite such inconsistencies what counts as more important for this noir author is the evocation of a plight from which there is no escape. The novel's epilogue, echoing verbatim but condensing its prologue, seals the idea of fate's circularity by having Helen/Patrice reflect: "I don't know what the game was. I'm not sure how it should be played. No one ever tells you. I only know we must have played it wrong, somewhere along the way. I don't even know what the stakes are. I only know they're not for us. We've lost. That's all I know...And now the game is through" (254). Although she and Bill are genuinely in love, their suspicion of each other as accountable for Georgesson's death means that sooner or later they will part. "There's no way out," realizes Helen/Patrice at the novel's start. "We're caught, we're trapped. The circle viciously completes itself each time" (10). Perhaps because Woolrich's bleak vision of life as a zero-sum game so dominates both The Bride Wore Black and I Married a Dead Man, neither novel contains the trace markers of World War II's impact on the home front as can be ferreted out from Rendezvous in Black. Admittedly, these indicators are not abundant: the prewar Saturday-night ritual of dating in small-town America when cinema was the main form of entertainment; the lingering economic impact of the Great Depression; the loss of young husbands owing to the draft; railroad cars filled with caskets of slain soldiers; the allure of the big city shortly before a demographic shift to the suburbs; and the increased prosperity of the United States not long after the war's end. Collectively, however, these elements in Rendezvous in Black suggest that even so retiring and manic-depressive a writer as Woolrich could not escape the imprint of his momentous time. In light of Tony Hilfer's judgment that "Cornell Woolrich's distinction [is] to have created one of the most consistently ontologically pathological worlds of any crime novelist, specialists in paranoid perception as they are" (35), it comes as somewhat surprising that ten years later David Cochran's study of American noir during the postwar era does not mention Woolrich as an antecedent. Before his death in 1968 the prolific author had published twenty-seven novels, many in pulp editions under pseudonyms, and 223 short stories collected in fifteen anthologies. His prodigious output confirms his odd attachment to "Remington Portable No. NC69411," the typewriter that figures in the dedicatory blurb of The Bride Wore Black and that is also the subject of his posthumous autobiography's first chapter. Claiming there that "I was born to be solitary" and that "[t]he path you follow is the path you have to follow; there are no digressions permitted you, even though you think there are" (Blues 4, 14), Woolrich was undoubtedly a haunted man. The chronicler of his career posits that this writer was "a chameleon" whose "life and work are riddles without solutions," but Woolrich may have provided a clue in a handwritten fragment found among his papers posthumously and apparently considered as an ending for Blues of a Lifetime: "I was only trying to cheat death...I was only trying to stay alive a brief while longer, after I was already gone. To stay in the light, to be with the living, a little while past my time” (Nevins 122; Woolrich 152). Given the sense of personal doom under which this author labored throughout his life, readers are fortunate that at least one of his novels coincided with a post-Depression mood on the American home front during World War II.

Notes 1. Sam B. Girgus begins an essay on 1938 as follows: "Still in the midst of the Great Depression and suffering from accumulated woes of poverty, unemployment, poor housing, economic inequality, Jim Crow racism, and social injustice, most Americans probably hoped and thought they had survived the worst of times and could look forward to change for the better. In fact, the country stood at the gates of hell...The death instinct, the irrational, and the incurable division of the Western psyche started to bud in its preparation for a full flowering of death and destruction" (206). 2. The year can be inferred from Woolrich's reference to a time when "the draft law was already beginning to be felt and standards were going down" (20). The first peacetime conscription in United States history was imposed when Congress passed the Burke-Wadsworth Act on 16 September 1940. 3. Woolrich's sentimental evocation of Dorothy as "everyone's first love" is consonant with an incident he recounts in his posthumously published Blues of a Lifetime, though the short volume is less an autobiography than "a memoir meant more to deliver the poetic truth of Woolrich's life than its factual details" (Irwin 125). The book's maudlin second chapter recounts his "first-time love" at age nineteen for Vera Gaffney, an Irish working-class girl (31). Probably a fabrication because Woolrich was secretly homosexual (see Nevins 73-77, 217), the tale centers on a birthday soirée at which Vera, like Cinderella, proves to be the belle of the evening. The next afternoon, though, the first-person narrator is not met at their usual rendezvous site, a nearby park bench, and is spurned by Vera's parents. Roughly a year later, if Woolrich's récit is to be believed, the star-crossed lovers encounter one another again by accident at a block party, but after they start to dance together Vera is picked up by sinister-looking older men in a black sedan that "could have resembled a coffin." The vignette ends on` this plangent note: "We never saw each other again, in this world, in this lifetime. Or if we did, we didn't know each other" (67). 4. After this passage Woolrich expands on the frenetic nature of 1940s swing and jive routines: "He spread his legs and shot her through to the other side, like a mail sack going down a chute, then braked her and jerked her back again, and she – miraculously – found her feet once more and stood upright before him. Then he bent down and rolled her across his back, from the left side to the right, and dropped her down to the floor" (69).

Works Cited Cassuto, Leonard. Hard-Boiled Sentimentality: The Secret History of American Crime Stories. Columbia UP, 2009. Cochran, David. American Noir: Underground Writers and Filmmakers of the Postwar Era. Smithsonian Institution P, 2000. Gates, Philippa. "Home Sweet Home Front Women: Adapting Women for Hollywood's World War II Home-Front Films." Americana: The Journal of American Popular Culture, 1900 to Present, vol. 15, no. 2, 2016, https://americanpopularculture.com/journal/articles/fall_2016/gates.htm Girgus, Sam B. "1938: Movies and Whistling in the Dark." American Cinema of the 1930s: Themes and Variations, edited by Ina Rae Hark, Rutgers UP, 2007, pp. 206-226. Hilfer, Tony. The Crime Novel: A Deviant Genre. U of Texas P, 1990. Hutchinson, George. Facing the Abyss: American Literature and Culture in the 1940s. Columbia UP, 2018. Irwin, John T. Unless the Threat of Death Is Behind Them: Hard-Boiled Fiction and Film Noir. Johns Hopkins UP, 2006. Nevins, Francis M., Jr. Cornell Woolrich: First You Dream, Then You Die. Mysterious, 1988. O’Brien, Geoffrey. Hardboiled America: Lurid Paperbacks and the Masters of Noir. 1981. Expanded ed., Da Capo, 1997. Reid, David, and Jayne L. Walker. "Strange Pursuit: Cornell Woolrich and the Abandoned City of the Forties." Shades of Noir: A Reader, edited by Joan Copjec, Verso, 1993, pp. 57-96. Shanken, Andrew M. 194X: Architecture, Planning, and Consumer Culture on the American Home Front. U of Minnesota P, 2009. Stock, Karin Anette. "Die Angst hat tausend Augen: Metaphern der Vergeblichkeit im Werk Cornell Woolrichs." Die Horen: Zeitschrift für Literatur, Kunst und Kritik, vol. 37, no. 1, 1992, pp. 96-103. Woolrich, Cornell. Blues of a Lifetime: The Autobiography of Cornell Woolrich. Edited by Mark T. Bassett, Bowling Green State U Popular P, 1991. ---. The Bride Wore Black. 1940. Penzler, 2021. ---. I Married a Dead Man. 1948. Penguin, 1994. ---. Rendezvous in Black. 1948. Modern Library, 2004.

|

Journal Home

AmericanPopularCulture.com