Dorothy Richardson’s 1905 novel The Long Day: The Story of a New York Working Girl, As Told by Herself exemplifies cultural fascination with the oppression of marginalized people. Popular literature fed this fascination during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries: books by Helen Hunt Jackson, Jacob Riis, Upton Sinclair, and others called attention to Native Americans, immigrants, as well as the poor and sometimes inspired palpable social reforms. Jackson’s bestselling novel Ramona (1884), for example, raised sympathy for the plight of indigenous people. Ramona directly contributed to legislation intended to improve land rights and promote sovereignty (Senier 17). Female wage earners also received attention in the late nineteenth century, and Cathryn Halverson characterizes readers’ interest in them as “almost obsessive” (96). The Long Day transports that interest into the twentieth century by shifting the focus from the New England mill to the urban factory. The novel is the best-known example of the reform-oriented exposés that proliferated around the turn of the century, a genre which speaks to the popular culture’s attraction to and anxiety about class, labor, and justice. Equally important, the novel’s attention to the intersection of class and gender, prescient for its time, enriches its examination of labor and distinguishes it from similarly structured narratives.

Richardson, an American born in 1882, shares a name with the better-known British author of the Pilgrimage novels who was born in 1873. The American author is a turn-of-the-century prototype for Barbara Ehrenreich: The Long Day exposes the poor working conditions of so-called unskilled jobs and the near impossibility of surviving on their wages in much the same manner that Ehrenreich’s New York Times bestseller Nickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting by in America (2001) later would. The Long Day helped to forge the “honored journalistic tradition” (Gallagher) of what Ehrenhreich characterizes as immersion journalism, an investigative approach that often employs deception to reveal injustice. Richardson’s novel originally was published anonymously with the claim that its middle-class author had gone undercover to live as an unskilled laborer, as Ehrenreich later would. The Long Day draws now-familiar conclusions about the dangers and demands of blue-collar labor, and the high costs of basic necessities. It arguably primed privileged readers for fiction from the working-class and immigrant woman’s perspective, such as Anzia Yezierska’s story collection Hungry Hearts (1920) and novel Bread Givers, which the New York Times reviewed favorably in 1925. Working-class fiction is difficult to define given the amorphous yet fundamentally binary construction of class, but it is a broad genre that has generated a wealth of scholarship.1 Yezierska’s fiction, for instance, has received renewed attention from feminists, labor historians, and scholars of ethnic American literature since the 1970s (Hefner 188).

Like Nickel and Dimed, The Long Day was a bestseller, both as a serial (in American Magazine during 1903-1904) and in three editions published between 1905 and 1906. The popular response was strong, and the novel was a critical success as well. At the time, readers debated whether or not Richardson’s portrayal of working women was truly authentic. Initially, some questioned the legitimacy of Richardson’s account of the life of a wage-earning urban woman, while others praised its accuracy. Middle-class and working-class readers ultimately reached consensus and accepted the book as truth. In spite of its success and its deft negotiation of the era’s social, economic, political, and gender issues, The Long Day largely has been forgotten. Some might regard the flaws of Richardson’s novel as grounds for neglected status. The Long Day replicates the class prejudices of its time, including moral conservatism and the narrator’s unawareness of her own position of privilege. Nevertheless, I argue for a re-evaluation of The Long Day in light of its resonance with early twentieth-century readers as well as its relevance to twenty-first century debates. More than a century after it chronicled a nameless woman’s attempts to make a living as a housekeeper, a box maker, a manufacturer of artificial flowers, and a laundry worker, The Long Day lends insight and nuance into feminist analyses of early twentieth-century modernity and the New Woman in America, to include a clear picture of privileged women’s perceptions of female workers. This examination is important because much of the scholarship on New Woman literature has focused on British writers such as Sarah Grand, Ouida, and Mona Caird. Richardson sheds light on the way gender troubles labor for less-privileged U.S. women, and she subtly criticizes the socioeconomic power structures that prevent entry into the middle class. The Long Day’s sustained critique of a charitable institution overseen by elite women pointedly examines their collusion with the oppression of the working class. Ultimately, the novel uncovers the class prejudice of privileged women -- especially those who mean to help female workers -- as a key obstacle to working-class women’s pursuit of gender and economic equity.

Today, the phrase gender trouble conjures Judith Butler’s influential 1990 book of the same name and its argument that gender is a performance.2 Early twentieth century Americans did not understand gender as a performance. However, The Long Day demonstrates awareness of the specific concerns women faced at the intersection of gender and class, and it recognizes class as fundamentally performative. For example, the narrator observes that residents in a home for needy women are expected to demonstrate an ingratiating “attitude of charity dependents” (285). In addition, workers in the box factory flout the cultural conventions used to ascribe class status, which draws attention to the fact that class norms, like gender norms, are constructed products of culture. Butler’s discussion of gender misperformances argues that “the strange, the incoherent, that which falls ‘outside,’ gives us a way of understanding the taken-for-granted world of sexual categorization as a constructed one” (149). Similarly, Richardson’s representation of workers unashamed of their status and uninterested in mimicking the behavior of the dominant group reveals both the women’s seeming strangeness and the constructed nature of the taken-for-granted world of class categorization.

In order to understand fully how Richardson’s novel challenges representations of gender and class typical in early twentieth-century fiction, we must situate it within the transnational literary and ideological context of the New Woman. Sally Ledger describes the New Woman as “middle- and upper-class [in] orientation” despite being “repeatedly linked with socialism and with the working man” (35). Thus, New Woman literature did not fully realize its populist ambitions, and the turn of the century became “a lost cultural moment, when the opportunities for an alliance between feminism and socialism were often half-grasped, but never fully worked through” (Ledger 37). Such missed connections emerge before the turn of the century in novels, including Louisa May Alcott’s Work: A Story of Experience (1873), which constructs a middle-class woman’s choice to seek fulfilling employment as “a new Declaration of Independence” without recognizing that this choice was not available to all (1). Similarly, New Woman authors including Ouida and Charlotte Perkins Gilman often support the labor movement without engaging with it or while overlooking the class advantages they enjoy. According to Ledger, “‘New Women’ and ‘Working Men’ were not fit fictional subjects” for Ouida (35). Gilman’s utopia Herland (1915) establishes work as crucial to a well-rounded, fulfilling life, yet the novel limits its conception of labor to highly trained professions typically pursued by the privileged. Moreover, Herland literally renders invisible the “unskilled” work of food preparation, maintenance, and manufacturing, which unseen hands perform just as they did in the homes of privileged readers. This is a strange development given that Gilman ascribes social and monetary value to housework in What Diantha Did (1910) by portraying those who perform it as skilled employees deserving fair wages and working conditions.

Nevertheless, as Dolores Hayden has shown, Gilman envisioned a hierarchy of labor in which working-class women helped middle-class women pursue white-collar jobs by cleaning the homes, preparing the food, and caring for the children of their employers (195). The Long Day offers a more realistic examination of workers than other fin de siècle New Woman writers. Richardson applies the New Woman ideal of personal liberty to working-class women, but she resists the tendency to ignore them or to idealize their seeming independence. However, the novel maintains the assumption, widespread at the time and informed by evolutionary theories including eugenics, that privilege corresponds to merit. The women’s movement of the era, which overlapped with New Woman ideology, “promoted racism as part of its overall program” (Hausman 494). For instance, birth control pioneer Margaret Sanger regarded contraception as “the conveyor of racial efficiency” (Hausman 494). The Long Day does not endorse eugenics, but the biases of the narrator’s privileged subject position contribute to judgmental remarks about fellow workers, such as the description of their speech as “vulgar and silly” (157). Bias also shapes the recommendations The Long Day makes for helping women workers, including the suggestion that they improve their minds by reading literature the narrator selects.

The problematic result is that The Long Day interprets the challenges of working-class women through the lens of middle-class femininity. Richardson attempts to ventriloquize the oppression of a group to which she does not belong, an undertaking that is often unsuccessful. Yet this tradition is longstanding in popular American reform literature; works by Richardson’s contemporaries, such as Sinclair’s The Jungle (1906) – as well as titles from Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852), Black Like Me (1961), and New York Times bestseller The Help (2009) – relate suffering and injustice from an outsider’s perspective. The prominence of ventriloquism attests to an uncomfortable fact: stories of oppression tend to gain more recognition when told by an outsider who emphasizes the negative. Writer/activist Michelle Tea recognizes this point in her observation that poor and working-class people “are written about, rarely telling our own stories”; she likewise laments, “it’s always the tragedy that is documented” rather than positive qualities like strength or resourcefulness (xiii). Moreover, writing about poor and working-class people tends to “reveal” the obvious: Tea’s reaction to Nickel and Dimed is “Duh… Of course minimum-wage work is bone-crushing drudgery, difficult to live on, even more difficult to get out of. Why did it take a middle-class woman on a well-paid slumming vacation to break this news to the world?” (xiv).

The same question might be asked of The Long Day. However, Richardson’s middle-class perspective works to mediate working-class suffering for privileged readers in a way they might better understand, a technique employed successfully in work published before and since The Long Day. Cindy Sondik Aron argues that the novel’s privileged point of view “enhances its usefulness by revealing not only a sympathetic and largely accurate account of the lives of working-class women, but the perceptions of middle-class readers and reformers as well” (xi). Moreover, privileged women writers like Richardson long have enjoyed greater access to publication. The Long Day’s instant success in 1905 attests to the public appetite for an outsider’s look into the world of women’s wage labor. Cathryn Halverson recognizes that classism informs the novel’s interest in working-class women, which she interprets as a mixture of attraction and revulsion (96). While Halverson reads this fact as evidence of Richardson’s nearly homoerotic longing for intimacy with them (107), the narrator’s mixed emotions about her fellow workers more broadly reflect privileged women’s involvement in cross-class benevolence. Yet Richardson’s descriptions of youth and beauty marked by labor and struggle likely tantalized middle-class readers.

The novel’s device of thrusting an educated young woman with a middle-class background into the world of work lends a similarly titillating quality that may have contributed to its popularity. The same device also makes possible The Long Day’s exposé: a woman born into the working class could not compare it to the narrator’s former life. Lost advantages give her keen awareness of her new status as “[a]n unskilled, friendless, almost penniless girl… utterly alone in the world” with a new life consisting of “to live and to toil” (5). As she arrives in New York City from western Pennsylvania in search of employment, the whistles of the trains and the toll of the ferry bells seem to warn “WORK OR STARVE, WORK OR STARVE!” (5). This warning signals the narrator’s recognition that her welfare, indeed her survival, rest solely in her own hands: the great risk she assumes along with autonomy, mobility, and some ability to self-determine undercuts their sweetness. Richardson’s realistic portrayal of the narrator’s perilous status counters the emphasis on feminist possibilities at the expense of the cost that resulted in the work of contemporaries including Gilman glossing over the harsh truths of working-class women’s lives.

The Long Day’s subsequent scathing account of privileged women’s charitable efforts constitutes criticism of their misguided actions as well as the class hierarchies that the privileged perpetuate. A Foucauldian reading of the narrator’s stay in a home for needy women uncovers Richardson’s attempt to portray the institution as a means through which privileged females control and police their beneficiaries. In The History of Sexuality, Michel Foucault revealed the complexity of power and control, which reach far beyond the justice system. Power, he wrote,

must be understood in the first instance as the multiplicity of force relations immanent in the sphere in which they operate and which constitute their own organization; as the process which, through ceaseless struggles and confrontations, transforms, strengthens, or reverses them; as the support which these force relations find in one another, thus forming a chain or a system, or on the contrary, the disjunctions and contradictions which isolate them from one another; and lastly, as the strategies in which they take effect, whose general design or institutional crystallization is embodied in the state apparatus, in the formulation of the law, in the various social hegemonies. (92-93)

Power, then, can take a variety of forms, including hierarchies, relationships, conflicts, and procedures. At the charitable institution in The Long Day, these forms of power paradoxically conspire to reinforce economic hierarchy, ensuring that the privileged women running the organization retain their advantages while the working-class women they ostensibly help remain disadvantaged. The contrast between the institution’s spotless appearance and corrupt reality condemns organized philanthropy, revealing that the ability of women workers to thrive is compromised by forces beyond their control. The home, like other charitable organizations in The Long Day, does more harm than good. Richardson indicates early on that opportunists have exploited the ties between religion and charity, sullying the reputations and efficacy of reform groups. Miss Jamison, who runs boarding houses for workers in neighborhoods “shabby though eminently respectable,” is one such schemer: she shrewdly names her properties after nearby churches and consequently fills “The Calvin” with Presbyterians and “The Wesley” with Methodists (8).

The narrator’s stay in the home for girls further problematizes charitable organizations. Prior to her arrival there, she characterizes self-respect as “more a matter of material things than of moral values” because “[i]t is possible for a hungry woman to walk with pride, and it is possible for the immoral and utterly degraded woman to hold her own with the best of her sisters… if only she is able to maintain her usual degree of cleanliness and good grooming” (153). This remark indicates that for the narrator, “cleanliness and good grooming,” or the rudiments of good taste and middle-class aesthetics, overwrite morality and respectability. To be poorly groomed is to lack self-respect and to appear déclassé since poor grooming is associated with destitution. Thus, the narrator experiences the lack of self-respect brought on by going without a collar and two days without bathing as a horrifying loss of status that she refers to as an “infinitely greater terror” than hunger or loneliness (153). However, the contrast between the spotless appearance and the corrupt truth of the home for working-class girls belies the narrator’s conviction and further condemns the charity. The door of this unfriendly place is a “black coffin” (157) and its reception room “partook somewhat of an ecclesiastical aspect,” decorated with “a series of scriptural texts, all of which served to remind one in no ambiguous terms of the wrath of God toward the forward-hearted and of the eternal punishment that awaits unrepentant sinners.” These “vindictive utterances” are interspersed with pictures “of a religious or pseudo-religious nature” (158).

One of these images draws the narrator’s attention: a romanticized depiction of a young woman clinging to an anchor in a roiling ocean, her eyes turned toward the sun peeping through dark clouds. Entitled “Hope leaning upon Faith,” the image reminds the narrator of her own situation. The irony is that the charity home, with its Draconian policies and corrupt staff, indeed resembles a heavy anchor rather than a buoyant life preserver. Clinging to it will sink homeless women sooner than lift them up from need and despair, illustrating how the institution reinforces socioeconomic hegemony and class hierarchy to keep power in the hands of the powerful. While the women boarding at the institution may sustain themselves through hope and faith, the women running it have no hope for them, no faith in them, and no faith in their charitable enterprise.

Richardson typifies charity workers as unfeeling old maids who cannot understand the recipients of their aid, and do not wish to. The individual who answers the narrator’s knock on the door eyes her “coldly” and greets the narrator contemptuously (159). The housekeeper is “the personification of neatness, if such be the word to characterize the prim stiffness of a flat-figured, elderly spinster” (159). The word spinster suggests a privileged woman who has turned to charitable activity through a lack of other prospects, namely marriage. Doing so permits the unnamed housekeeper to maintain dignity and propriety despite a lack of interest in her work. Since she cannot reveal her dislike for charity work to others of her class, she expresses it toward the charitable cases with “hard-faced” expressions (159), a “sharp, metallic voice” (158), and an “acid-like” manner (159). The matron of the institution, evocatively named Mrs. Pitbladder, proves more evil than the spinster at the door. She has “the very sort of face in which one would have expected good nature to repose,” but Mrs. Pitbladder lacks both good nature and compassion for the young women she is supposed to help (171).

Inmates of the institution must pay their room and board, which conflicts with its benevolent purpose: how can the destitute afford to pay? That payments must be made in advance makes even less sense given that most are out of work, like the narrator, and therefore particularly in need of shelter. The institution’s policies exploit vulnerable women, ensuring that they remain disadvantaged. Exposing this fact reveals the inherent defects of middle-class philanthropy and charitable institutions, along with the corruption of individuals working within these systems. We see Mrs. Pitbladder intimidate vulnerable young women into serving as personal slaves who must deliver her meals and crimp her hair. She also steals from the destitute by refusing to make change when they pay rent. The institutional governance Mrs. Pitbladder exemplifies – indifferent at its best and corrupt at its worst – has deep roots reaching to its disinterested board of directors, “ladies who sometimes came to look at the dormitories and the bath-rooms and then went away in their carriages” (171). Perfunctory inspections constitute the extent of the board’s involvement in the home over which Mrs. Pitbladder presides. The board members have no interaction with the staff, the inmates, or the daily operations of the organization, and they have no interest in becoming more engaged. Once they look into the dormitories and bathrooms, these privileged women leave satisfied with their charitable work and with themselves. Their satisfaction signifies complicity with the socioeconomic hierarchy that offers privilege for them at the expense of their beneficiaries. The board members’ lack of involvement reflects class bias that turn-of-the-century women reproduced when they infiltrated leadership positions previously held almost exclusively by men. Ignoring opportunities for improvement, the female directors examine superficial cleanliness rather than the efficacy of the home’s programs and managers, or the condition of its residents.

Richardson calls for alternative forms of relief in response to the fraught power structure within the institutional model. She uses The Long Day to recommend assistance for working-class women in two unusual formats. The first is the distribution of classic novels, which Richardson imagines necessary to working-class women’s socioeconomic advancement. Putting canonical literature into the hands of these workers, many of whom are immigrants, will improve their literary taste. When the narrator introduces factory colleagues to Little Women, they recognize that Alcott’s verisimilitude makes the March family “sound like real, live people” (86). This recognition suggests that appreciation for novels promoting middle-class morality can be taught. Better taste in literature in turn will help working-class women to mirror the speech of privileged people, open their minds to new ideas, and, most importantly, impart good (read middle-class) values. Richardson characterizes these changes as assets that enhance upward mobility, for the working-class girls presently speak in a manner that marks their status. With different models, they may speak more like the educated narrator.

The box-factory workers love to read, so perhaps literature may prove a useful means of intervention. Richardson attempts to show their need for middle-class literature through their ignorance of it and their preference for melodramas full of ornate flourishes. Melodramas inspire the workers to give themselves fancy names out of their favorite sensational stories. As one young woman explains, “It don’t cost no more to have a high-sounding name” like Georgiana Trevelyan, Goldy Courtleigh, Gladys Carringford, Angelina Lancaster, or Phoebe Arlington (96). Only Henrietta Manners does not assume a fancy alias, but Richardson later reveals Henrietta to be just as bad, for she once assumed the more religious-sounding name Faith Manners because “it sounded better for a professing Christian to have some name like that” (131). The workers’ plan to co-opt status with an elaborate alias backfires with the narrator, who dismisses the names for coming from “trashy fiction” (81) for uneducated audiences rather than the “simple, every-day classics” that she enjoys, “that the school-boy and -girl are supposed to have read” (85).

The narrator identifies “classics” as texts including Gulliver’s Travels, David Copperfield, Les Misérables, and, of course, Little Women. These texts were relatively contemporary to the publication of The Long Day in comparison with traditional, canonical classics from the ancient Greeks. They also were written in English, with the exception of Les Misérables. Richardson’s identification of Swift, Dickens, Alcott, and Hugo as equivalent to classical authors is a move similar to the one John Guillory describes New Critics making in their revaluation of the canon. The act of choosing a new set of classics “gave the emerging bourgeoisie access to cultural capital that had previously been available only to clergy and aristocrats” (Guillory 136). In The Long Day, the narrator’s identification of classical authors and texts demonstrate her own access to the cultural knowledge that distinguishes middle-class women.

The narrator’s comparisons between her values and the box-factory ideals assume that middle-class aesthetics are superior. Furthermore, they demonstrate Richardson’s belief that refashioning lower-class women in the image of the dominant group would improve their circumstances. Contemporary feminists recognize the flaws of this chauvinistic, assimilationist approach, but for Richardson and others of the era it seemed logical given the power of the privileged. Reformers including Jane Addams assumed imitating Protestant values and middle-class taste would enhance social, economic, educational, and housing opportunities. To this end, programs at Hull-House encouraged immigrants from Eastern Europe to appreciate classics of Western European literature and to read them in English.

The Long Day goes beyond promoting assimilation to characterize it as the means of neutralizing class conflict. The purpose of good taste in literature, according to John Guillory, “was to unify the nation culturally just as Standard English was supposed to unify it linguistically” (136). Though Guillory refers to the unification of England, this concept relates to The Long Day’s efforts to unite American women under the leadership of the middle class. Privileged women like Richardson’s narrator represent ideal ambassadors of early twentieth-century literary sensibility: education, social connections, magazine subscriptions, and leisure time for reading bring familiarity with the new classics.

Entertaining gentlemen friends in a parlor is another middle-class behavior The Long Day would have working-class women emulate. Used for social ceremonies including courtship, the parlor became a potent signifier of the middle class during the nineteenth century. As Katherine C. Grier notes, “[s]etting aside a specific room for the purposes of social rituals and furnishing it for that use – once a prerogative only of families of means – became an activity that denoted membership in, or aspirations to belong to, the most important culture-defining group” (64-65). The tenements and boarding-houses in which working-class women live lack parlor space in which to entertain gentlemen friends respectably. As a result, female workers – including those in The Long Day – bring men into their boarding-house bedrooms, effectively ruining their reputations in appearance if not in reality.

Mrs. Pringle, the landlady at a lodging where the narrator briefly resides, describes the disastrous results of Annie’s decision to bring a man into her room at the boarding house. Like Stephen Crane’s eponymous Maggie, Annie makes a series of small mistakes that quickly escalate into her ruin and culminate in homelessness, prostitution, and death. Mrs. Pringle’s account of Annie’s story follows the typical “fallen woman” tale, inflected with conventions of “trashy fiction” characteristic of the dime novels popular with the working class. “Trashy fiction,” according to Richardson, is an “ungrammatical, crude, and utterly banal rendition of the claptrap morality exploited in cheap story-books” characterized by obsessive focus on “the frailty of woman” (89). Where Crane’s nuanced portrait in Maggie: A Girl of the Streets (1893) depicts a number of forces conspiring to destroy a defenseless girl, “trashy fiction” blames the victim and constructs her ruin as inevitable based on her inherent flaws.

Mrs. Pringle’s story employs these tropes. Annie comes to the city “a nice, innocent girl” (37) who “started out to live honest” (38), but her weakness for fine things brings about her downfall. Mrs. Pringle’s description of Annie as a woman who “hankered for fine clothes and to go to theaters, and there wasn’t any chanst for neither on four dollars a week” is both ungrammatical and trite, establishing Annie as responsible for what happens to her (38). Annie unwisely did not marry the young man she turned to for diversion. Mrs. Pringle blames Annie, not the man, for Annie’s descent into homelessness and prostitution because “when a young fellow sees that a girl ’ll let him act free with her, and then he don’t want to marry her, no difference how much he might have thought of her to begin with” (38). Exposure to fancy clothes and urban entertainments in the city elicit Annie’s weakness, leading her to covet material things beyond her means. A boyfriend is one of those too-costly items, since the room she rents does not include a place to receive male callers. When she brings the man in anyway, Annie slides down the slippery slope into ruin.

For this reason, Richardson makes her second recommendation for reform: providing working-class women with parlors. This change would allow girls like Annie to entertain men in accordance with middle-class morality and aesthetics, preserving their reputations and preventing others from Annie’s fate. The way to achieve parlor access is to revolutionize housing options for working-class women, modeling them on hotels for working-class men. In the novel’s epilogue, Richardson writes, “We need a well-regulated system of boarding- and lodging-houses where we can live with decency upon the small wages we receive” (285). These should not be “any so-called ‘working girls’ homes’” like the corrupt institution that charges rent and expects gratitude (285). Instead, Richardson envisions her alternative as empowering women workers to achieve independence and live more like middle-class women. The parlor is a venue for taste – a place that women can decorate and use to display both their possessions and themselves – and a status symbol. Decoration was the foundation of the orthodox parlor, which typically included paintings or prints, women’s handiwork, family photographs, Bibles, ceramic figures, and other items to communicate “the cultured façade of the parlor owners” (Grier 89-91). Ensconcing working-class women and their male visitors in this moral, “cultured” environment would instill in them middle-class taste and values.

Yet the female workers do not admire the middle class, but rather despise anyone unlike them: they shun the narrator, who does not share their taste in pastimes or speak the way they do. Richardson may seem critical of working-class women, but her depiction of their resistance to the dominant culture endows them with autonomy often lacking in the work of New Woman writers such as Caird and Gilman. As Henrietta Manners puts it, the narrator’s way of speaking strikes the workers as “high-toned” and full of “big words and all that” (117). Demonstrating her lack of middle-class manners and education, Henrietta warns the narrator, “you ought to get yourself over it as quick as you can; you ain’t going to have no lady-friends in the factory if you’re going to be queer like that” (118). Henrietta exemplifies the factory workers’ “bigotry and intolerance” through her belief that any “act, word or occurrence out of the ordinary rut set by box-factory canons of taste and judgment, must be condemned with despotic severity” (120). In spite of her narrow mindedness, Henrietta’s opposition constitutes a discrete epistemology and value system that offers an alternative to middle-class hegemony and a subtle critique of the hierarchy of privilege.

Henrietta calls the narrator’s difference “queer,” lesser rather than finer, indicating that the factory girls may be more likely to ostracize the narrator than to imitate her. The Long Day codes the box-factory workers’ distrust of the dominant culture as a need for education, but Richardson simultaneously makes visible an existing working-class women’s culture. Additionally, Henrietta’s biases constitute resistance to having her taste improved, resistance that may stem from a rational fear of alienating herself from her community. Box-factory workers rely on “lady-friends,” or fellow workers who support them in the workplace, and the narrator struggles without sufficient lady-friends. Additionally, this community could be all Henrietta or any female worker has, and the narrator’s stay in the charity home makes clear that privileged women offer neither assistance nor empathy.

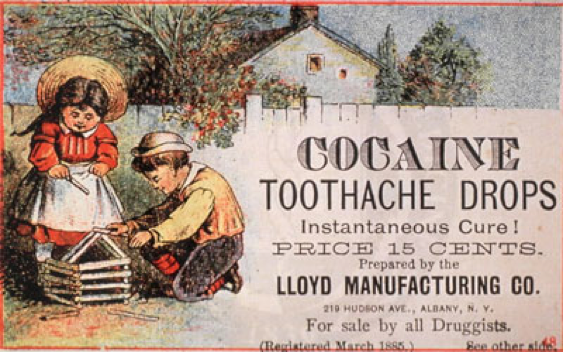

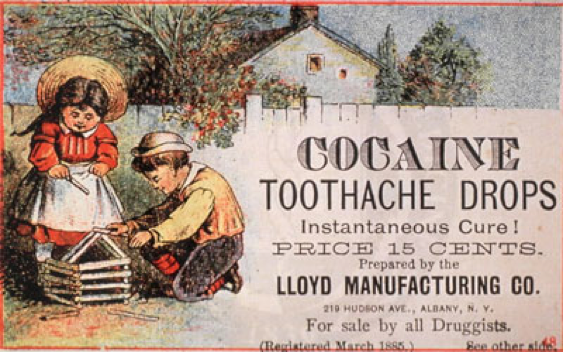

But Henrietta’s intentional assumption of outsider status among her fellow workers demonstrates that she is not a full member of a community of working-class women. Only Henrietta refrains from participation in a social organization called the Ladies’ Moonlight Pleasure Club, pretending that her faith prohibits such behavior. As she explains, “I don’t believe in dancing” because “[o]ur church’s down on it” (95). Henrietta’s faith proves false when the narrator visits her rented room and finds stolen goods and empty cocaine bottles. Touted for its invigorating and pain-relieving affects for people of all ages prior to the turn of the century, cocaine later was marketed to workers as illustrated in Figure 1 below. It certainly could have helped Henrietta remain alert and productive during long, physically strenuous shifts at the box factory, where pay corresponds to productivity. The drug also might have suppressed Henrietta’s appetite, offering a potentially more economical option than food. Indeed, the narrator describes feeling insatiable hunger at the end of her factory shifts, while Henrietta has little appetite.

Figure 1

Ignoring the systemic oppression contributing to Henrietta’s theft, drug use, and outlook, Richardson reverts to the hands-off approach of the board of directors of the workers’ home, which she criticized so harshly in another part of the novel. Unfortunately, the narrator’s discoveries about Henrietta lead her to determine that Henrietta is “physically, mentally, and morally doomed” rather than misguided (120). The narrator feels no sympathy, regarding Henrietta as a hopeless case unworthy of assistance and gives up on reforming her. Apparently, she considers Henrietta incapable of change and undeserving of resources or assistance. As a result, the narrator becomes a part of the social hegemony that oppresses women workers and makes it impossible for them to change their circumstances. Paradoxically, in its condemnation of Henrietta, The Long Day also takes on some of the characteristics of the “trashy fiction” it repeatedly disparages by blaming the victim like a sensational thriller rather than critically examining the intersection of factors that contribute to her downfall.

Richardson depicts other female workers as deserving of empathy and help. She also reaches out to working-class women by dedicating the novel to her three “lady-friends”: “Happy, fortunate Minnie; Bessie of gentle memory; and that other, silent figure in the tragedy of Failure, the long-lost, erring Eunice, with the hope that, if she still lives, her eye may chance to fall upon this page, and reading the message of this book, she may heed” (1). The dedication consists of a moral directive that fortifies Richardson’s vision of middle-class women as moral and cultural instructors to working-class women, whose lives may depend on compliance. Failure to “heed” will result in “the tragedy of Failure” like the wayward, aimless Eunice and the lying, thieving Henrietta Manners (1). Thus the novel itself constitutes a call to action for privileged readers by exposing oppression and corruption. The dedication indicates Richardson’s hope that The Long Day inspires middle-class women to action and educates the working-class women who read it. In this way, The Long Day itself attempts to act on behalf of the female workers it describes, taking to heart its emphasis on the importance of reading and literature.

Too long forgotten, The Long Day constitutes a potential ideological link between the New Woman literature that ignores or romanticizes working-class women and the socialist feminist writing that more explicitly and productively addresses the oppression of workers. At the same time, the novel perpetuates class prejudices inherent in New Woman literature because it reinscribes middle-class hegemony even as it calls for reform. Richardson’s work deserves re-examination both in spite of and because of its shortcomings. The Long Day’s limitations are characteristic of the reform novels and exposés in demand during the early twentieth century as well as the cultural preoccupations with class that fueled their popularity. Thus, the comparison between Richardson’s novel and Ehrenreich’s Nickel and Dimed does not hold true in all respects: the texts are as different ideologically and stylistically as the historical and cultural moments that produced them. Fiction was a popular means of exploring class and injustice at the turn of the century, but workers practically have disappeared from American fiction. Instead, contemporary writers employ nonfiction and journalism to address oppression, which may seem more authentic but also coincides with the virtual disappearance of the worker from American literature.

Historian Robert S. MacElvaine speculates that Americans lost interest in fiction about the working class because “workers have never fit the self-image that Americans like to maintain,” an image built upon the American dream and continuous upward mobility. “It is permissible to be a laborer early in life,” according to this imagined trajectory of success, but “he who remains an industrial worker is seen by most Americans as unsuccessful” since “no one aspires to be a worker” (MacElvaine). Twenty years after McElvaine published this essay, the majority of Americans identify as middle class despite increasing wealth gaps between the rich and the middle class. The popularity of the middle-class self-image has worked to gentrify American fiction, including fiction by women. Only one of the most popular bestselling novels by women of the past five years, The Help, addresses working-class women.3

On the other hand, The Long Day raises questions that maintain perennial importance. What is ethical journalism? What are the most effective modes of reform? Who should give voice to the oppressed? How do authenticity and power shape the telling of stories of inequality? Additionally, the undercover reporting and immersive journalism Richardson uses remain prevalent in American news, entertainment, and other forms of media, from Norah Vincent’s book Self-Made Man: One Woman’s Year Disguised as a Man (2006) to television shows such as What Would You Do?, which has aired on ABC’s Primetime since 2008. In a 2012 book analyzing undercover reporting that inspired a companion research database hosted by New York University, Brooke Kroeger called the technique a “great American tradition” dating to the nineteenth century which has never gone out of style (xv). Many recent documentary films, from Born into Brothels (2004) to Blackfish (2013), raise similar questions about ethics and ventriloquism even when they do not involve deception in reporting. Understanding of works that came before, including The Long Day, provides fundamental context for these titles. Moreover, The Long Day offers a valuable look at life for turn-of-the-century working-class women in America that demonstrates how a privileged female contemporary viewed them, a view which was disseminated among a wide readership.

Notes

1. Laura Hapke counters cultural amnesia about labor history in Labor’s Text: The Worker in American Fiction (2001), a study ranging from the antebellum period to the 1990s. Hapke observes that the Progressive Era “solidified earlier literary attempts to decouple femininity from workplace and leisure culture” as increasing numbers drew attention to immigrant women working in urban sweatshops (97).

Michael Denning’s Mechanic Accents: Dime Novels and Working-Class Culture in America (1987) demonstrates that workers constituted the primary readership of dime novels, not middle-class boys as previously thought. In fact, dime novel reading became interchangeable with “lower class” reading and sparked debates about its negative effects in the Atlantic Monthly (Denning 52). Dime novels followed one of two narrative structures: melodramatic and sensational or uplifting and moral (Denning 60-61). Examination of these mass-produced, popular texts, Denning argues, uncovers insight into the concerns of nineteenth-century working-class Americans, to include “escape from the narrative paradigms of middle-class culture” (61). Lauren Berlant’s The Female Complaint: The Unfinished Business of Sentimentality in American Culture (2008) helps us understand how literature contributes to a “women’s culture” which imagines that the female experience has universal elements. Within this culture, Berlant argues, melodrama and sentimentality pose subtle challenges to patriarchy. In Sentimental Modernism: Women Writers and the Revolution of the Word (1991), Suzanne Clark assesses high modernism’s rejection of sentimentality and its toll on female writers who inherited a women’s literary history tied to this tradition. Women writing work-class fiction at the turn of the century, including Dorothy Richardson, also inherited the legacy of sentimentality.

In the essay “What is Sentimentality?” (1999), June Howard advocates moving away from debates about sentimentality’s merits. Instead, Howard advocates “conceptualizing it as a transdisciplinary object of study” distinct from sentiment and domestic ideology (63-64). Sentimentality remains relevant because “one can scarcely find a canonical author… who is not drawing on or in dialogue with the tradition” (Howard 74). To that end, Sentimental Men: Masculinity and the Politics of Affect in American Culture (1999) uncovers the association between sentimentality and masculinity and its roots in the eighteenth-century “man of feeling.” As separate spheres ideology took hold, sentimentality was linked to women and the home. In their introduction to Sentimental Men, Glenn Hendler and Mary Chapman note that by the 1850s “the culture of sentiment became less directly identified with public virtue and benevolence and more associated with women’s moral, nurturing role in the private sphere of the bourgeois family” (3). Subsequently, in literature “crying mothers and dying daughters” replaced the “man of feeling” and “sentiment, sympathy, and sensibility became thoroughly feminized” (Chapman and Hendler 4).

2.

Butler argues that “the action of gender requires a performance that is repeated” to reinforce an established set of cultural meanings (191, original emphasis). Repetition obscures the origins of gender and naturalizes what is socially constructed; the fiction of binary, discrete genders becomes naturalized and imagined as necessary (Butler 190). Butler identifies the performance of gender as “bodily gestures, movements, and styles of various kinds” (191).

3. Two of the most popular New York Times bestsellers of the past five years written by women have male protagonists, Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch (2013) and Sara Gruen’s Water for Elephants (2006), which is set during the Depression. The other two, Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl (2012) and E.L. James’ Fifty Shades of Grey (2011), center on educated, professional women.

Works Cited

Alcott, Louisa May. Work: A Story of Experience. New York, NY: Schocken Books, 1977.

Aron, Cindy Sondik. Introduction to The Long Day: The Story of a New York Working Girl. By Dorothy Richardson. Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia, 1990. ix-xxxv.

Berlant, Lauren. “The Female Complaint.” Social Text 19/20 (1988): 237-259.

Butler, Judith. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. New York, NY: Routledge, 2006.

Chapman, Mary and Glenn Hendler. Introduction to Sentimental Men: Masculinity and the Politics of Affect in American Culture. Ed. Mary Chapman and Glenn Hendler. Berkeley, CA: U of California P, 1999. 1-16.

Clark, Suzanne. Sentimental Modernism: Women Writers and the Revolution of the Word. Bloomington, IN: Indiana UP, 1991.

Denning, Michael. Mechanic Accents: Dime Novels and Working-Class Culture in America. Rev. ed. New York, NY: Verso, 1998.

Ellison, Julie. Cato’s Tears and the Making of Anglo-American Emotion. Chicago, IL: U of Chicago P, 1999.

Foucault, Michel. The History of Sexuality: An Introduction, Volume I. Trans. Robert Hurley. New York, NY: Vintage, 1990.

Gallagher, Dorothy. “Making Ends Meet.” The New York Times. The New York Times Online, 13 May 2001. Web. 5 Jan. 2015.

Grier, Katherine C. Culture and Comfort: Parlor-Making and Middle-Class Identity, 1850-1930. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press, 1988.

Guillory, John. Cultural Capital: The Problem of Literary Canon Formation. Chicago, IL: U of Chicago P, 1993.

Halverson, Cathryn. “The Fascination with the Working Girl: Dorothy Richardson’s The Long Day.” American Studies 40.1 (1999): 95-115. Web. 22 Dec. 2014.

Hapke, Laura. Labor’s Text: The Worker in American Fiction. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers UP, 2001.

Hausman, Bernice L. “Sex before Gender: Charlotte Perkins Gilman and the Evolutionary Paradigm of Utopia.” Feminist Studies 24.3 (1998): 489-510.

Hayden, Dolores. The Grand Domestic Revolution: A History of Feminist Designs for American Homes, Neighborhoods, and Cities. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1981.

Hefner, Brooks E. “‘Slipping back into the vernacular’: Anzia Yezierska’s Vernacular Modernism.” MELUS 36.3 (2011): 187-211. Web. EBSCOhost. 24 June 2015.

Howard, June. “What Is Sentimentality?” American Literary History 11.1 (1999): 63-81.

Kroeger, Brooke. Undercover Reporting: The Truth about Deception. Evanston, IL: Northwestern UP, 2012.

Ledger, Sally. The New Woman: Fiction and Feminism at the Fin de Siécle. New York, NY: Manchester UP, 1997.

MacElvaine, Robert S. “Workers in Fiction: Locked Out.” New York Times. The New York Times Online, 1 September 1985. Web. 23 June 2015.

Richardson, Dorothy. The Long Day: The Story of a New York Working Girl. Charlottesville: UP of Virginia, 1990.

Senier, Siobhan. Introduction to Ramona. By Helen Hunt Jackson. Buffalo, NY: Broadview, 2008. 15-31.

Tea, Michelle. Introduction to Without a Net: The Female Experience of Growing Up Working Class. Ed. Michelle Tea. Berkeley, CA: Seal Press, 2003.

|