A Man Called Horse:

Western Melodrama and Southern Gothic

Americana: The Journal of American Popular Culture

(1900-present), Spring 2020, Volume 19, Issue 1

https://americanpopularculture.com/journal/articles/spring_2020/phillips.htm

Southern Illinois University

This article concerns a relatively neglected Hollywood Western, rarely addressed in critical discourse but vividly remembered by cinephiles, both lay and professional. A Man Called Horse, released in 1970, is an adaptation of a short story by Dorothy Johnson, first published in Collier's magazine in 1950. Johnson is best known as the source author for another cinematic Western adaptation, John Ford's canonical The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962).1 A Man Called Horse belongs to a much older genre that has been subsumed into the Western, the so-called Indian captivity narrative. In this story form, a settler of European extraction is kidnapped by indigenous people, lives among them for a time, and is eventually redeemed to white civilization. Evincing an ambivalence endemic to the Western genre, the captivity narrative fluctuates between an exoticizing fascination with the primitive and an ideological imperative that the protagonist withstand the temptation to "go native." According to a longstanding theory, genre narratives foster social cohesion by imaginatively resolving intractable contradictions within dominant ideologies (Cawelti, Adventure 35-36). In the case of the captivity narrative, at least if the protagonist is male, his temporary encounter with this savage way of life is thought metonymically to rejuvenate his decadent culture, as is exhaustively elaborated in Richard Slotkin's frontier myth trilogy. Johnson's variation on this theme in "A Man Called Horse" runs as follows: John Morgan, an upper-class white man, leaves behind his privileged existence in order to test his mettle on the frontier of the Northwestern Territory during the second quarter of the nineteenth century. Taken captive by an Indian2 raiding party, he is treated as a slave and given the name Horse. Over the course of many trials and tribulations, he adapts to native ways and eventually regains human status by killing a member of an enemy tribe and appropriating his horses. Morgan

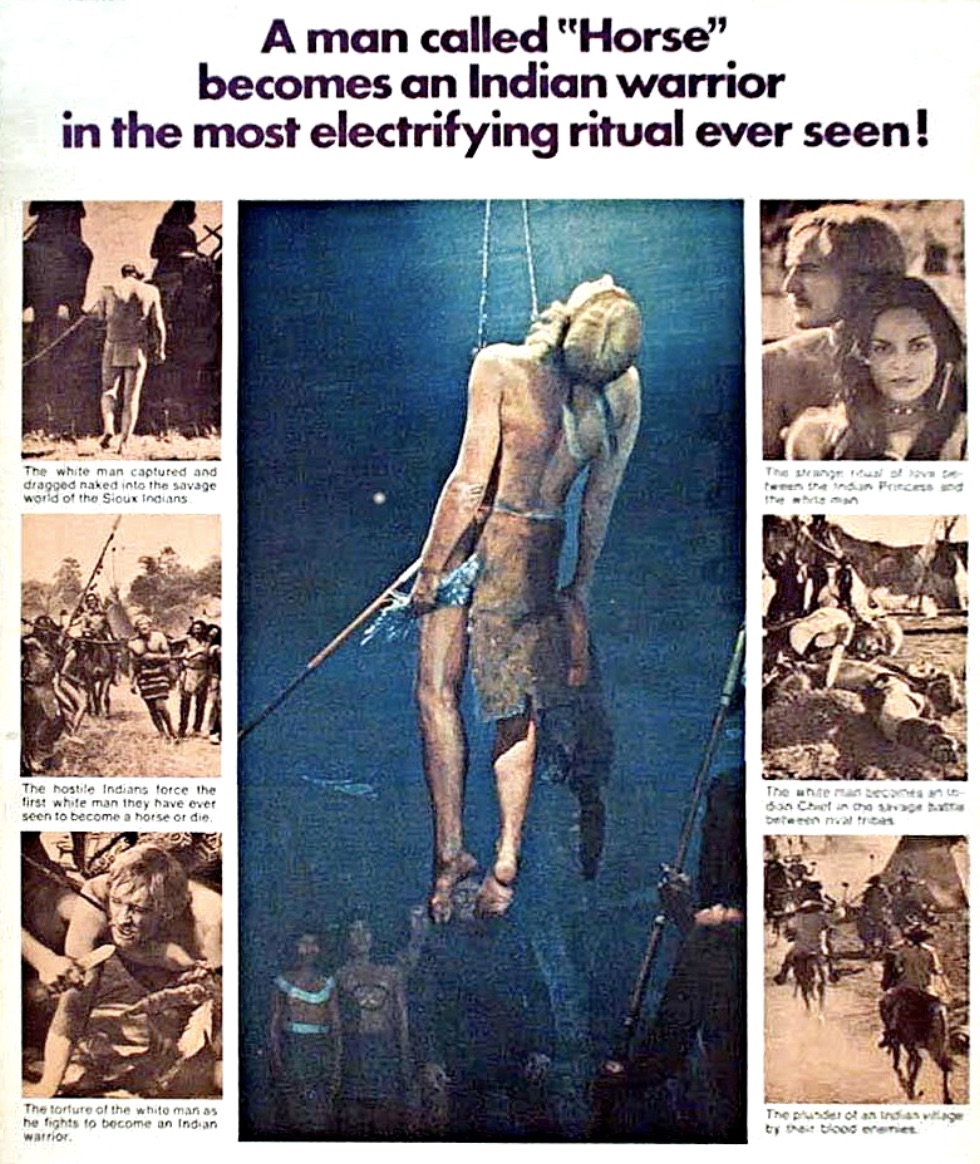

uses this newfound property as the bride price to wed the chief's sister. His new brother-in-law soon dies in battle, and Morgan's wife subsequently dies in childbirth. He must then decide whether to stay and care for his mother-in-law, who now has no living relatives. This he somewhat reluctantly does until the time of her death. He finally returns home, having proved himself, as Johnson's narrator puts it, "the equal of any man on earth" (24). The captivity narrative, on the other hand, tends to problematize borders, whether geographical, temporal, or racial. As Gary Ebersole has argued, "Captivity represents an ultimate boundary situation.... In such situations, the body is a painful register of the shattered or porous boundaries of inside and outside, self and other, past and present" (7). The redemption of the captive seems to reinstate those boundaries, but this narrative resolution cannot contain the troubling questions raised in the story's middle. The horrific experience of captivity, especially the terror of contamination by a monstrous other, characterized as a manifestation of some primeval darkness or sin, moves us away from melodrama and toward the gothic. As Teresa Goddu has shown, "the American gothic is haunted by race" (7). Unlike melodrama, "the gothic tells of the historical horrors that make national identity possible yet must be repressed in order to sustain it" (10). Given its thematic interests in impurity and contamination, it should be no surprise that "the gothic seeps into other genres and appears in unlikely places" (Goddu 8), which is precisely what happens in the process of adapting "A Man Called Horse" for the screen. While the film's plot generally follows Johnson's template, her narrative is interrupted by one crucial departure. The captive protagonist must undergo a gruesome initiation ritual in order to achieve full membership in the tribe and marry the chief's sister. This rite of passage, the Sun Vow, involves being hung from the ceiling of a medicine lodge by ropes attached to two bone splints pierced through the skin on either side of the chest.3 It is this set-piece, which Johnson referred to as "this bloody scene which really makes the movie" (Mathews and Healey 165), that spectators tend to remember, even if the film's other hundred minutes are not especially memorable. The peculiar layout of the film's one-sheet poster, which reveals key elements of the narrative in chronological order, graphically illustrates the relative importance of the Sun Vow scene by making its depiction massively larger than the other six plot points (see Figure 1). Initially reading the left side of the poster vertically from top to bottom, the viewer's eye must then diagonally traverse the shocking central image in order to complete the narrative sequence from top right to bottom right. This visual progression indicates the Sun Vow's spectacular disruption of the smooth narrative flow among the smaller images. At the same time as the vertical sequences on each side reveal more of the plot than typical film posters of the period, the central image hides from view the most gruesome aspect of the Sun Vow, Morgan's wounds, prompting a desire to see more.4 I argue that the addition of this scene, like its placement in the poster, amounts to a gothic irruption into a melodramatic frame. This apparent contradiction between narrative modes cannot be resolved internally. Rather, the somatic rupture of the Sun Vow accomplishes the film's central ideological work: to reconstitute a white identity that some believe has been diminished and fragmented in the post-Civil Rights Movement era. As Sally Robinson has demonstrated, this narrative of white backlash tends to uphold a synchronic, binary view of "a singular, pitched battle between the white man and his various others." To the contrary, she argues that "normativity, constantly under revision, shifts in response to the changing social, political and cultural terrain" (4). The twenty-year interval between story and film thus affords a clear view of how the idea of whiteness mutated between 1950 and 1970. Slotkin's historical contextualization frames the film as pandering to 1960s youth counterculture's obsession with Native American aesthetics while failing to innovate beyond a standard Western plot (Slotkin, Gunfighter 630). However, both film and story display significant departures from conventional Westerns, in terms of geography (east of the Mississippi River), temporality (prior to the Civil War), and sociohistorical context (pre-industrial). These three peculiarities point toward the largely neglected though abundantly manifest connections between the West and the South. Despite the direct historical linkage between the admission of new states to the Union concomitant with westward expansion and the political struggle over the question of slavery, this nexus is almost never overtly addressed. The evacuation of this historical context also leads to a general (though not universal) absence of blackness in the Western film genre's racial ideology, in which whiteness is constructed through a negative binary relationship with indigeneity. As one of the few Western stories that features enslavement as a key narrative component, A Man Called Horse belies the Western's insistence on its discontinuity with the plantation. I. Viewing A Man Called Horse through its generic literary lineage offers a genealogical perspective on the ideological construction of whiteness in the Western. Consider two of the foundational Western texts, James Fenimore Cooper's Last of the Mohicans (1826) and Owen Wister's The Virginian (1902). Despite the divergent thematic interests of the two authors, they are often seen as occupying the same linear trajectory toward the cinematic version of the genre. Wister borrows plot devices from the melodramatic stage to build a narrative that culminates in a companionate marriage, metonymically ensuring the foundation of a white nation on the frontier (Wexman 130-132). Conversely, Cooper's frontier novels are replete with doomed Romantic affairs involving a multiplicity of racial identifications. Wister's cold, Anglo-Saxon eugenics also present a stark contrast with the gothic irrationality and ambiguity that Cooper adopts from sentimental novels of the previous generation like Charles Brockden Brown's Edgar Huntly (Ringe 108-110). The purity of whiteness in Wister skirts the gothic problematic of hybridity.

In contrast with the gothic mode's obsession with guilt, melodrama emphatically disavows culpability. The official optimism to which Roberts refers is characteristic of the melodramatic mode as delineated by Linda Williams: "Melodrama begins, and wants to end, in a space of innocence," usually located in a rural past, often in the antebellum South (65). Moreover, "The greater the historical burden of guilt, the more pathetically and the more actively the melodrama works to recognize and regain a lost innocence" (61). Of course, the most forcefully articulated cinematic expression of melodramatic racial ideology is D.W. Griffith's Birth of a Nation, particularly the sequence in which the pastoral idyll of Flora, the youngest daughter of the plantocrat Cameron family, is disrupted by the violent sexual advances of the monstrous freedman Gus (Diawara 767-75). In the tradition of Cooper's Cora, the white woman throws herself from the cliff where Gus has cornered her. Subsequently, her elder brother, the "Little Colonel," mobilizes the newly formed Ku Klux Klan to lynch Gus. The intertitle immediately following Flora's death reads, "For her who had learned

the stern lesson of honor, we should not grieve that she found sweeter the opal gates of death." In other words, she averted the fate-worse-than-death without having to use the last bullet. Richard Maltby has argued that the controversy over the film's overt racism at the time of its initial release forced the diversion of its ideology into more subtle expressions: "the threat of the sexual Other migrated elsewhere, among other places, to its dormant position in the Western, where it is several times disguised" (48).

Disavowing any relationship between Southern and Western lynching, the Judge expressly denounces the fascination of the crowd with gothic spectacle and their subsequent implication in the guilt for this horrific deed. By framing the lynching of cattle rustlers as a depersonalized expression of popular justice, the Judge maintains the innocence of the executioners and the Manichean morality of melodrama. The cowboy's internal struggle and ultimate determination to choose "frontier justice" over personal sentiment amounts to a melodramatic revelation of his "moral occult." According to Peter Brooks, this interior quality "demands to be uncovered, registered, articulated" in melodrama, usually through the protagonist's suffering or sacrifice (20-21). Johnson's melodramatic mode of storytelling is clearly indebted to Wister's. For instance, she maintains the trope of the virginal schoolteacher tutoring the antisocial male protagonist in manners and mores, while also providing him a redemptive character arc when he finally accedes to her wishes and settles down for good. Like Molly, Morgan's bride "delighted in educating him" (Johnson 15). While the miscegenation taboo precludes an exact parallel with Wister's ending, Morgan's acceptance of the role of caretaker for his mother-in-law fulfills the same function of exposing his moral occult. Beyond these standard plot points, Johnson adopts Wister's Social Darwinist notions of "natural aristocracy," a status based on individual prowess rather than noble heredity (Slotkin, Gunfighter 176). As the Virginian tells Molly, "Some holds four aces...and some holds nothin’, and some poor fello’ gets the aces and no show to play ’em; but a man has got to prove himself my equal before I’ll believe him" (144). As it so often does in Westerns, the game of poker becomes metonymic of grander conflicts, in this case between skill (meritocracy) and luck (heredity). Johnson echoes Wister's antidemocratic notion that the superior specimens of mankind, or "the quality," possess a natural right to rule over the unwashed, undifferentiated masses, or "the equality." Morgan goes West "to find his equals. He had the idea that in Indian country, where there was danger, all white men were kings, and he wanted to be one of them. But he found, in the West as in Boston, that the men he respected were still his superiors, even if they could not read, and those he did not respect weren't worth talking to" (1). In other words, Morgan's fantasies of claiming his birthright are quickly dispelled by the hegemony of meritocracy, which obtains not only within the United States proper, but also already on the frontier and, presumably, all the way to the Pacific. Among the men Morgan respects are those he hires to guide him on his existential expedition. While Johnson barely mentions them, in Jack DeWitt's screenplay they are downgraded to stereotypical hillbillies. Their cinematic characterization plays on a longstanding prejudice in American culture against Appalachians, who have often been framed as congenitally retrograde, inbred "crackers" (Isenberg 105-132). Morgan, meanwhile, is transmogrified from Boston Brahmin to English Lord, further distancing him from his employees and risking the admission of hereditary social classes on the frontier. The contrast provided by the guides' tragic inbreeding, the mirror image of miscegenation, assuages this risk. In an essay on British characters in Western films, Jack Nachbar argues that figures like Morgan "confront the primitive coarseness of the frontier and in doing so are reborn, shedding their class consciousness and stuffy manners for individualism, democratic classlessness, and invigorating informality" (168). But the opening scene of the film shows that Morgan, despite having traversed the Northwest Territory for the past five years, is no closer to American egalitarianism than when he first arrived. He makes a clumsy attempt by imperiously demanding that his

grizzled old guide, Maddock, call him by his first name rather than "Your Lordship." When Maddock responds with "And you may address me as 'Joe,'" his toothless, hillbilly grin is played for a laugh, mocking any suggestion that the two men could ever be considered equals. In their illiteracy, drunkenness, and general ill breeding, Morgan's guides hardly present an ideal model of a democratic citizenry. Instead, they project a retrogressive, excessively hereditary kind of whiteness that Morgan must reject in order to construct a superior, meritocratic brand of whiteness that can legitimate his inherited social status. Morgan's desired equality is to be found not in the erasure of social class, but in the transposition of racial identity. Whereas the former is properly accomplished in melodrama's revelation of the moral occult, the latter invokes the gothic's fatal bloodlines.

II. In his transitional stage between being white and becoming Indian, Morgan experiences an abjection into the status of a beast of burden. He becomes, for all intents and purposes, a horse. In arguing for the underlying connections between the myths of South and West, Cawelti notes the centrality of the horse to both, particularly as a symbol of a declining socioeconomic system that is rapidly being superseded by industrialization (Six-Gun 76-77). The historical role of the horse as a marker of nobility is clearly operative in the Western, as is evidenced in the return of the Spanish loan-word caballero (gentleman) to its linguistic roots to refer to anyone who rides a horse. Its etymological cousins, chivalry and cavalry, lie at the heart of the racist ideologies of protecting white womanhood and venerating the Lost Cause of the Confederacy, which itself has been transposed into the Western mythos as Custer's Last Stand. "When the South lost the War," writes Colin Dayan, "its brutal, sweet, and vanishing world was kept alive in [its horses'] gently curving haunches." However, these same horses "also bore the pesky contradictions of slavery on their backs" (43). Cawelti detects an ambivalence present in the horse's "special linkage [with] black slaves" who are "often shown to have a special understanding or skill with horses" (Six-Gun 77). Beyond this literal association, still operative in the twenty-first century in the form of Deadwood's freedman livery master Hostetler, the analogical connections between horses and slaves in terms of social status and economic function is a central subtext in both versions of A Man Called Horse. The intervening years between the publication of Johnson's story in 1950 and the release of its cinematic adaptation in 1970 straddle the conventional, if whitewashed, periodization of the Civil Rights Movement, from Brown v. Board of Education in 1954 to the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968. By the time Collier's first printed the story, the plantation myth was already becoming taboo in Hollywood filmmaking (Bogle 76). Despite the apparently radical departure of inserting the Sun Vow, the adaptation maintains and hyperbolizes Johnson's theme of sacrifice and its concomitant racial coding. While the film retains Morgan's acceptance of his adoptive mother at its conclusion, the narrative logic of the source material is undermined by the far greater spectatorial impact of the ritual sequence, to the extent that the film's ending is utterly anticlimactic. Russell Reising has argued that texts whose "failed endings" resist clear-cut structural exposition "can't close, precisely because their embeddedness within the sociohistorical worlds of their genesis is so complex and conflicted" (11). A Man Called Horse engages in a strange attempt to integrate the Myths of the South and the West while also addressing a contemporary moment in which those ideologies are being questioned. A Man Called Horse is an early example of what Claire Sisco King has identified as the "sacrificial film," which "deploys images of and narratives about male suffering, death, and redemption as strategies for reconstituting dominant notions of the subject, the nation, and the masculine" (6). Unlike most protagonists of sacrificial films, Morgan does not die, but like them, his sacrifice has a clear Christological inflection. The unsubtle messianic overtones of Morgan's ordeal are again manifested in the peculiar layout of the film's poster (see Figure 1). The image in the center features a spear poking into Morgan's side, which is bound to bring up associations with centuries of pictorial representations of Christ's crucifixion. It also guides the viewer's eye from the lower left to the upper right as it traverses the various tableaux, making the surrounding, smaller images analogous to the Stations of the Cross in a passion play.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Notes 1. For a general analysis of Johnson's role as source author for Western adaptations, see Metz who addresses Liberty Valance and The Hanging Tree (1959), but not A Man Called Horse. 2. I use this term to refer to cinematic representations of Native Americans in Westerns, in order to clearly differentiate cinematic caricatures from human beings. While I normally would use the name of the specific tribe or nation in question, this practice is complicated by the change from Crow captors in Johnson's story to Sioux in the film. Most of the characters' names are likewise changed between the story and screenplay. I have therefore avoided referring to the Indian characters by name, in the interest of consistency and clarity. 3. The design and staging of this ceremony are taken directly from the writings and paintings of George Catlin, a Pennsylvanian who went West in the 1830s to document what he considered to be rapidly vanishing indigenous cultures. Catlin's role as additional source author for this film adaptation is fascinating, but beyond the scope of the current discussion. 4. My thanks to Duncan Faherty for drawing my attention to the layout of this poster.

Works Cited Adams, Jessica. Wounds of Returning: Race, Memory, and Property on the Postslavery Plantation. U of North Carolina P, 2012. |

Journal Home

AmericanPopularCulture.com