Love in a Falling City:

David Hare's Saigon

and the Musical Miss Saigon

Americana: The Journal of American Popular Culture

(1900-present), Spring 2022, Volume 21, Issue 1

https://americanpopularculture.com/journal/articles/spring_2022/ma.htm

Michigan State University

Chris will come to me like the phoenix

Romance set against a city under siege or on the eve of falling into enemy hands has long been a literary trope to kill two birds with one stone, or to double the dramatic effect of tragic conflicts between political entities and characters. Even more so when Eros and Thanatos are pitted on the stage under time and spatial constraints of live performing arts. Sweet Eros and bitter Thanatos sharpen each other like biting a sugar cube as one sips scalding Turkish coffee, or Vietnamese coffee in the context herein. The panorama of a falling Saigon in 1975 accentuates the lovers ripped apart. The death drive to “do in” the other political party clashes with the sex drive to “do it” with the mate. As Saigon changes overnight to Ho Chi Min City, as the last US Marine helicopter roars off the Embassy roof, David Hare’s BBC/PBS Masterpiece Theatre screenplay Saigon: Year of the Cat (1983) as well as Claude-Michel Schönberg and Alain Boublil’s musical Miss Saigon (1989) culminate in the paradox of fall. Saigon falls and characters fall out of love, only to witness the rise of love as a romanticized, idealized affect. To stage the undying spirit of love amounts to a collective denial of, and at the minimum sugarcoats, the trauma of war and the mortality of human bodies, if not human love. Inspired by the Vietnam conflict, the Western playwright and, subsequently, musical composer and lyricist subconsciously kill yet another bird, the undead bird of the "yellow" race in their Orientalist representations, in addition to the two usual casualties of war – combatants and/as lovers. Whereas the socialist Hare centers Anglo-American "affairs," pun intended, at the expense of marginalizing the natives, the musical practitioners help themselves to the white male fantasy of Puccini's Madame Butterfly (1904). Saigon falls in the crosshairs of East and West. On the one hand, the vertical axis runs temporally through various hostilities, armed or cultural. The geisha or China Doll stereotype of white male fantasy calcifies in Pierre Loti's Madame Chrysantheme (1887). It resonates with, if not infects, Puccini's opera Madame Butterfly (1904), Hollywood films Love Is a Many-Splendored Thing (1955) based on Han Suyin's novel, The Teahouse of the August Moon (1956) based on Vernon J. Sneider's novel, and Sayonara (1957) based on James A. Michener's novel. That such films are sired from previous incarnations as novels demonstrates Hollywood's karma doomed to reprise the West's id of masculine hegemony over the Orient. As though anticipating the joint forces of Asians and Pacific Islanders in the millennial formulation of APIDA (Asian Pacific Islander Desi Americans), East Asian-centric white fallacy veers off to the South Pacific in Mutiny on the Bounty (1962) based on Charles Nordhoff's novel. The trajectory from print to film is streamlined in David Henry Hwang's stage play and ensuing film M. Butterfly (1993). Whereas white males never tire of conceiving Orientalist phantasmagoria, the off-white (yellow-ish) Asian-American Hwang gives the motif an ethnic, queer spin. A playwright of Asian descent comes to fulfill "racial castration" of Asian males from effeminate Charlie Chan and Fu Manchu to clowns like Mickey Rooney's Mr. Yunioshi in Breakfast at Tiffany's (1961). The forbidden love of East and West continues with timely political correctness and a certain level of ethnic awareness in David Mitchell's The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet (2010).

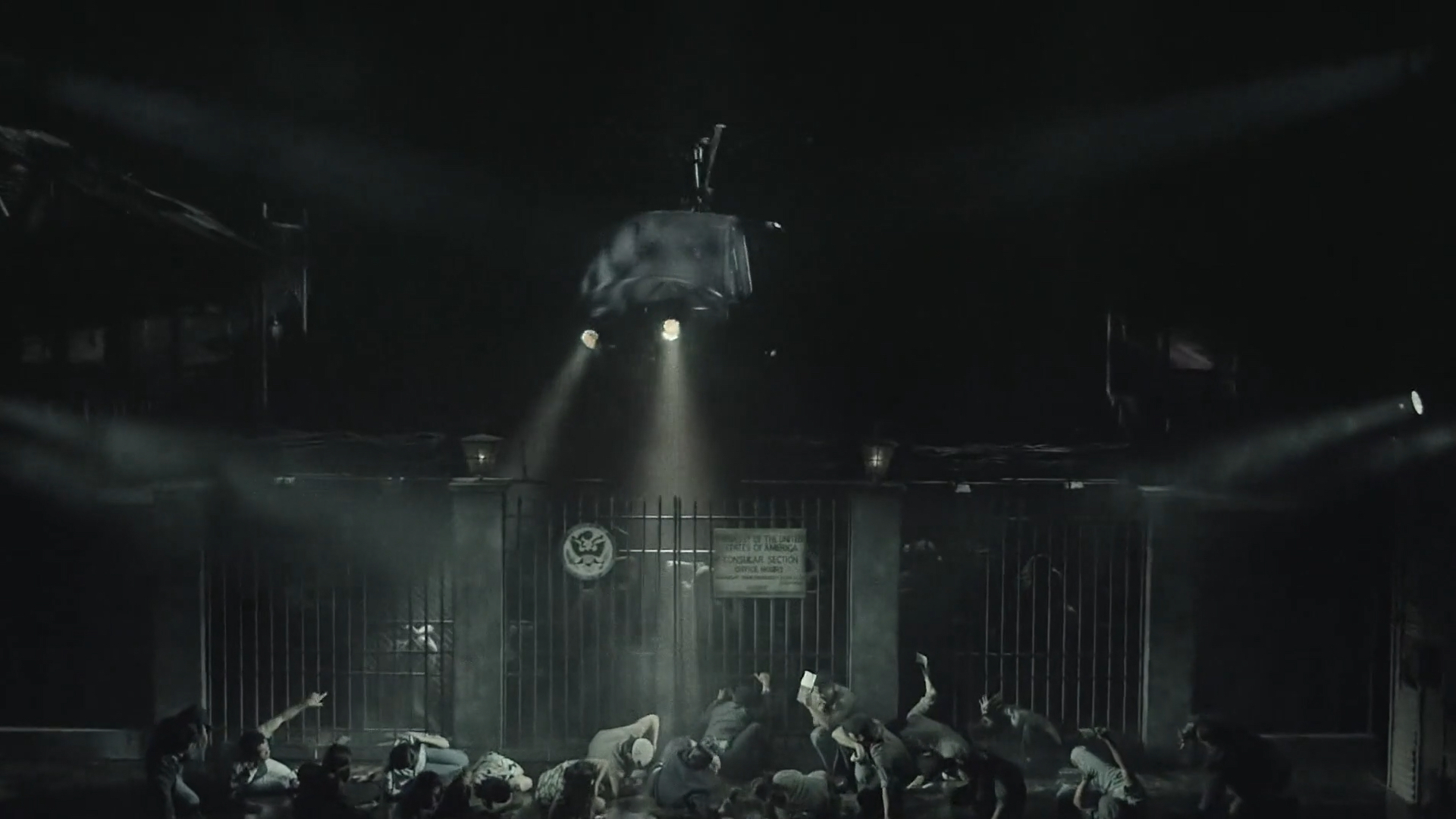

In space or in time, it matters little where and when romance comes to an abrupt halt. All alike as Orientalized stock images of symbolically castrated males and fetishized, hypersexualized females, the spread or centerfold of China Dolls, Japanese geishas, or Vietnamese bar girls constitutes but variations in the white masculinist discourse. Hence, the intersection of love and war in Vietnam heightens the dramatic tension in Saigon and Miss Saigon. Saigon: Year of the Cat is one of David Hare’s early plays in the 1980s. A socialist in conviction, the playwright appears to have worked out the kinks, or "chinks," pardon the expression, in his psyche before settling down in the new millennium to pen Anglo-American-centric BBC/PBS political dramas and TV movies: the thrilling Johnny Worricker spy trilogy that includes Page Eight (2011), Turks & Caicos (2014), Salting the Battlefield (2014), and, most recently, Roadkill (2020). In addition, mainstream filmscripts worthy of Hollywood such as The Hours (2002) and The Reader (2008) have added “white” feathers in his cap. Replaced are the “colored” ones from exotic lands: Maoist China and communist agitprop in Fanshen (1975) as well as the fall of Saigon in his 1983 screenplay, and postcolonial India in A Map of the World (1983). Now that Hare has "righted" himself from the leftist days of his youth, let us look back, wistfully, at the early works, Saigon in particular, to see how Hare managed to get the passion for revolution out of his hair. As his hair grays, the increasingly white filmic universe of the mature Hare is largely foretold by Saigon, its setting in Southeast Asia notwithstanding. Taking a page out of The Quiet American, Saigon focuses on the blooming of love between a 28-year-old, good CIA agent Bob Chesneau (Frederic Forrest) and a good-hearted English bank official Barbara Dean (Judi Dench) "almost 50" (211).1 Barbara has had a string of "secretive" assignations ever since her first "with a friend of my father's," once again implying a generational difference of May-December attraction (212). As Saigon opens in medias res of not only the war but also the romance, we even catch a glimpse of her one-time liaison with another bank employee Donald Henderson (Roger Rees), a Scotsman of 25. The wide gap in age and cultural background of what appears to be "the couple" (231) at the heart of Hare’s play augurs the eventual uncoupling of Barbara and Bob in the fall of Saigon as well as the divorcing of the old Vietnam from the young America. In Hare's progressive, albeit patronizing, false equivalence, Barbara with her British decency and stiff upper lip substitutes for the loss of Vietnam. Apples and oranges it seems – to be associating Barbara's flight and Vietnam's plight at all. But Eros and Thanatos are also binary opposites until Freud's shotgun marriage in Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920). As the lens through which the crumbling world is perceived, Barbara's in-betweenness impregnates the whole film, starting from the opening scene in her bedroom where she reclines in a restless siesta. This tableau sets the stage by fusing multiple strands: a lone English woman languishing in a "double bed" for a Spanish siesta in the French Indochina, as yet unaware of her American gentleman caller Bob. Her voiceover echoes that limbo state: "Afternoons have always hit me the hardest...Mornings are fine, there’s something to look forward to, and evenings, yes, I began to cheer up” (211). A riff on the Sphinx's allegory of the life course from the morning of infancy to noon hours of one's prime to the evening of senility, Barbara's interior monologue portrays the angst- and ennui-ridden mid-life crisis, deepened by the "no-man's" land – or bed, for that matter – she inhabits in Saigon. In that bed, the mise-en-scène is accompanied by the stage direction that "she is sweating slightly" (211), which points to the subtropical heat at high noon. Figuratively, though, she perspires under the purgatorial heat, slowly desiccating, despite a late bloom with Bob, into stage directions at the close of the play. "An old English spinster" in "a panama hat" is seen being evacuated in a helicopter, homebound to "my mother" in Bournemouth, England "where you go...planning to die” (287, 282, 221). The classic Plantation Panama hat is worn by an ex-colonist with a golden heart in a decolonizing Vietnam. That hat would be replaced overnight by the Viet Cong's topee or pith helmet, yet another residual of colonial fashions still trending under new management of Uncle Ho, having just ousted Uncle Sam. Indeed, the two jaws of the Western vise on Vietnam – politics embodied by Bob from the CIA and the US Embassy as well as money symbolized by Barbara's bank – shatter into smithereens in the wake of the Tet Offensive, the beginning of the end. Set in Vietnam, Hare's play betrays the colonialist characters' lifestyle that mimics and recreates England in denial of local conditions. The London Times, particularly the sports section, is pored over religiously by the bank manager Haliwell and other expatriates. Even Donald Henderson's outrage over English teams staffed with Scottish players on the other side of the globe seems out of place amidst a Vietnamese civil and proxy war. The Cercle Sportif, a French colonial club, offers night time socialization where Barbara plays card games with Americans and one Vietnamese, the Foreign Minister Van Trang (Rong Wongsawan). The games of "orthodox Acol" or "two clubs" are probably familiar to few other Vietnamese (216). Tied not only professionally but also personally to foreigners and their homeland, the Foreign Minister regrets not being able to attend Sports Day at Cheltenham Ladies' College in Gloucestershire, England, where his daughters’ study. Among Westerners and the Westernized Vietnamese elite, Barbara embodies white conscience. At the poker table, she compliments the all-girl English boarding school, but is soon distracted by bar girls propositioning in the adjacent main lounge. While upper-class Vietnamese women learn to be English ladies, their lower-class counterparts ply the oldest trade. Barbara’s playtime also coincides with prostitutes' worktime. Colonialists feign working for the natives to advance the colonial agenda and interest; colonized prostitutes feign play and erotic pleasure for survival. Barbara thirsts for love; her doppelgangers for johns with money. Her attention to the main lounge, in fact, causes the club to evict the working girls, who proceed to solicit in the shadows of the bush outside the club premises. The conscientious Barbara asks Judd (Wallace Shawn), Bob's CIA colleague, to give her money to them. In return, one woman asks, "Thank you. Number One. You wanna f--- me?" (219). As shocking as it may sound to the polite society, this rhetorical question is business as usual in transactional sex. But it betrays Barbara's act of kindness. Furthermore, it problematizes the first encounter of Barbara and Bob. In the shadow of war (and) prostitutes, Bob offers Barbara a ride since "the wheels" of the taxi "have finally fallen off" (219). Bob's ominous quip foreshadows the impending political crisis. The Ford Pinto in which Bob drives Barbara home happens to be CIA-issued, standard "spook" vehicle. Any individual affair in Saigon is already entangled with the body politic; those involved have to be transported there by the US and British airplanes, culminating in their rendezvous in a Ford subcompact car. Barbara's almost un-English forwardness in inviting Bob for a drink and more suggests the depth of her longing in the long afternoon of her life. While her invitation goes unreciprocated initially, Bob is the one with fallen wheels; he is gutless to engage emotionally. Although lacking reserve in her approach to Bob, Barbara exemplifies the proverbial English decency elsewhere. She organizes exit papers for a Vietnamese bank clerk, entertains obtaining more for the clerk's relatives, and almost defers to others the much-coveted slot in last transports out of the falling city in order to stay with Bob. Hare's characterization of Barbara countenances inconsistencies, unabashedly. Described as "definitely erotic" (211) in the opening bedroom pose, Barbara explains away her apartment's unlocked door to Bob: "No one wants a white English woman," which contradicts both her lounging sultry debut and her gentleman caller's "wants" (226). The veteran playwright surely sees the through line of a mature, uninhibited woman opening her door and herself to sexual advance, but he chooses to mask it behind the white lie of her undesirability. Undesirable to whom? Certainly, white males – Henderson, Bob, and even Judd – crave intimacy. This leaves local Vietnamese males to be the placeholder for "no one." Instead of a Barbara devoid of sexual charm, it comes down to Asian masculine impotence, incapable of mounting any wooing or "wounding." The broad-minded cosmopolitan writer lapses, perhaps subconsciously, into Orientalist racial castration. This charge stems as much from reading between the lines cited above as reading the lines themselves, especially the protagonists' dialogue with the indigenous characters. Quoc (Pichit Bulkul) is a bank employee, faithful and steadfast under duress, unruffled by Henderson's outburst. Quoc's Oriental "impassive[ness]" is as much a racialized construct as Henderson's Gaelic flare-up (238). Quoc even calmly covers for the bank manager Haliwell (Chic Murray) who has absconded. Meticulous and perspicacious, he counsels Barbara about leaving behind her "cardigan" to avoid arousing suspicion and mass panic in her final getaway (273). To veil their departures, the seasoned playwright directs to have both Haliwell's "coat" and Barbara's sweater left on the scene – an unwitting Freudian slip of colonialists' English attire entirely inappropriate in the tropics (274). Quoc's grace under fire reprises Haliwell's performance. Earlier and contrary to bank regulations, he disarmed a Vietnamese gunman demanding all his savings. Granted, Quoc faces no barrel of a gun, except his refusal to forsake his post at the bank would subject him to unimaginable misery meted out to Western collaborators once the Viet Cong takes over. Meant to provide a nativist anchor in the maelstrom on the eve of the communist takeover, Quoc's characterization stems from the stereotype of colonial subalterns serving white masters and institutions blindly. Hare’s liberal progressiveness resembles Orientalism in bifurcating Vietnamese masculinity: the good Quoc, who so borders on the automaton that his goodness looks suspect; and the bad Nhieu (Po Pao Pee), Bob's informant anxious for documents for himself and "some [of his] girls" to perhaps carry on pimping in the Promised Land (248). This unsentimental portrayal of a CIA asset approximates that of a depraved traitor, which is what the US turns into when Nhieu and countless other spies are left behind in Saigon, to be ferreted out one by one based on rows of file cabinets with 3x5 cards, all unshredded, unburned, exposed in prolonged shots of the deserted Embassy office. The BBC production directed by Stephen Frears follows Hare's stage directions closely, training the camera unblinkingly on those index cards: "Then we adjust to settle in the foreground on the drawer full of agents' name plates, forgotten on the desk. We hold on that" (293). But Frears recasts Nhieu, apparently no procurer of illicit sex in the TV movie, in a melodramatic scene where a young Vietnamese woman translates for the meeting. Bob, in fact, brings gifts of a six-pack of beer for Nhieu and a teddy bear for the girl. Ironically, alcohol would come into some use in one's final hours, but no toy can do time for the girl in a reeducation camp. Stereotyping Orientals coexists with caricaturing Yankees, particularly the US Ambassador played by E.G. Marshall, absent initially in the TV movie because he insists on being seen by his own dentist back in North Carolina. Upon return, the ambassador downplays Bob’s intelligence report on Nhieu’s doomsday scenario for the sake of securing an aid package from Congress, just as he did throughout the war exaggerating, playing up intelligence. Even more clownishly, he refuses to have documents incinerated for fear of polluting his swimming pool or having the old tamarind tree on the embassy compound chopped down to make way for the helicopter evacuation. Upon rejecting Bob's report outright, the ambassador looks up in reverie of his own, oblivious to the apocalypse unfolding on the ground and his subordinate's presence in the room. With his head in the cloud, so to speak, the ambassador launches into a dreamy tangent, quite an elaborate dramatization of Hare's simple direction "off on his own tack" (251), which serves to encapsulate American naiveté and wrongheadedness. Indeed, the way the Ambassador relaxes with outstretched neck reminds one of a guillotine looming over a nincompoop like Lu Xun's Ah Q.2 The only difference is that Ah Q and the Vietnamese would be decapitated, not the ambassador. The final retreat is communicated to Saigon's Westerners via a broadcast of Bing Crosby's "White Christmas," an encrypted white lie to avoid wholesale panic and chaos among the Vietnamese population. Whites are summoned to rendezvous at assembly points for the trip home as though it were Christmas. If Crosby's song were not factual, part of the historical absurdity of the Vietnam War, this heavy-handed finale would be a flaw sinking the screenplay. As it were, Crosby's mellifluous, heart-warming song culminates in the abandonment of Vietnam and the severance of the lovers homeward bound, respectively. Before mellowing into the mainstream BBC and Hollywood productions, the early socialist Hare borrows heavily from the like-minded Bertolt Brecht. Brechtian epic theater's alienation-effect seeks to break the illusion of the fourth wall, disrupting empathetic identification between characters on stage and the audience. Brecht theorizes that this detachment would give rise to a thinking – not just feeling – audience, calling them into action for social change. The dramaturgy of Fanshen, for instance, bears more than a family resemblance to Brecht's The Good Woman of Setzuan (1947) in having actors assume multiple roles, in directly addressing the audience, and in didactic, bald-faced pontificating on what is good and right. A Map of the World likewise mixes the filming in the studio setting with performers' "real" lives, even with the intrusion of "real" people portrayed by the actors. The caveat is that such "real people" remain performers, enacting a circular metanarrative that begs the question of reality and performativity. Also (mis)shaping the presentation of what the "real" is, for instance, A Map's distinct continental, leftist anti-Americanism in the beautiful yet "ugly" American character Peggy, whose dissolute sexual freedom turns her into one from America "the land of the fleas" rather than "the free."3 Although such practices transgress against the Western theater tradition, they are arguably inspired by Peking Opera conventions introduced to Brecht by the female impersonator Mei Lanfang and others in Moscow in 1935. Despite being part of the BBC programming, epic theater's fingerprint on Saigon is clearly visible in Scene 32 that closes Part One. The stage direction describes Barbara Dean turning, her "eye catches camera,” precisely at the point when her voice-over narrates: “Donald did leave with comparative dignity...Compared with some of the rest of us, I mean” (239). The violation of Stanislavsky's invisible fourth wall implicates the viewers in the coming shameful desertion of Vietnamese, as "the rest of us" includes whoever being gazed back at by Barbara Dean, if only Stephen Frears had executed Hare's direction. A further concession to the popular Masterpiece Theatre on both sides of the Atlantic, Dame Judi Dench who plays Barbara intones the final words while looking off-frame, away from the camera, inviting not spectatorial self-reflection through her accusing eyes, but the male gaze at her cleavage through the open blouse. Voyeuristic sex beats the vision of mass suffering and death; ratings from televisual pleasure trumps activism on social justice. Miss Saigon Miss Saigon picks up where Hare left off, on the eve of the fall of Saigon. Temporary continuum, however, does not guarantee stylistic kinship. Whereas Masterpiece Theatre director Frears forgoes some of Hare's provocateur as well as Brechtian alienation stance, not to mention sentimentalizing Vietnamese characters, Saigon the script and the teleplay remain scathing critiques of the US debacle in Southeast Asia. By contrast, the musical Miss Saigon is a modern version of Puccini’s opera Madame Butterfly (1904) without Hare's socialist bent and with a great deal more bathos. In his exploration of Saidian Orientalism collaging Puccini's Japan and Miss Saigon's Vietnam, Jeffrey A. Keith in "Producing Miss Saigon" argues that the West is addicted to "Southeast Asia's sexualized reputation," in which Saigon is gendered, "sensual and feminine" (248, 252). Feminizing Saigon, a DVD of the musical's 25th Anniversary Gala, performed live at Prince Edward Theatre, London, on 22 September 22 2014 is even packaged with an epigraphic photograph captioned "This photograph is the start of everything." The composer Claude-Michel Schönberg claims that his initial inspiration lies in that photograph “from an October 1985 France Soir news story that pictured a Vietnamese woman bidding a sorrowful farewell to her child, who was traveling to the United States to be with her father” (Keith 269). This melodramatic opening invites theatergoers to enter into an age-old story of East-West entanglements from Italian opera to Broadway-style musicals. As part of what Angela Pao calls the "maternal lineage," Puccini's plot is faithfully preserved: the innocent Vietnamese prostitute Kim (played by the Filipina Lea Salonga in its original London run and by Eva Maria Noblezada in the 2014 performance cited herein) at the brothel Dreamland falls in love with her American customer Chris and bears his son Tam after Americans have evacuated from Saigon (Pao 26). The boy-meet-girl scenario is made possible by the pimp Engineer (played by Jonathan Pryce in London) and by Chris's colleague John, indeed one of the johns at Dreamland. Having redeemed himself as an advocate for Amerasian children, "Bui-Doi" fathered and abandoned by American GIs, John reluctantly informs Chris after locating Kim and Tam in the post-US Vietnam, now that Chris is married to Ellen, who is American and blonde. Like her Japanese "ancestor" and the photographic epigraph, Kim commits suicide to free Chris from the moral choice and to give Tam a better life with his father in the US. Dreamland, under the tutelage of the Engineer, presents spectators with explicit sexuality as prostitutes peddle themselves to American soldiers. After erotic dancing, background copulating, and Broadway singing and dancing, Gigi is the newly coronated "Miss Saigon." Gigi wastes no time in asking the lottery winner for the night, none other than the African-American GI John, to "take me to America," which so revolts John that he shoves her off, despite her pledge to be a good wife while stroking his crotch. John reacts vehemently because Gigi violates the whole mirage of Dreamland set up to dispel the impending doom. The johns flee from the nightmare of Vietnam by indulging themselves in the pleasure of the flesh, while Gigi and her colleagues dream of safe passage by enduring the indignity and pain inflicted on their bodies. Indeed, even the Engineer clamors for a US visa by offering his "girls" or even himself in exchange. Rejected by John, Gigi bursts into song, one of the politically correct lyrics of "The Movie in my Mind" to counterbalance the salacious scene of transactional sex. Most significantly, Gigi sings of "Flee this life / Flee this place." Just as Gigi sets the stage of Saigon's abjection and precarity, Kim and the brothel chorus take over the song, refreshing the romantic dream. Ironically, the movie in Kim's and other actors' minds is less on the prostitutes' collective mental screen than in front of each theatergoer's or DVD viewer's eyes, on the stage or on the screen. Such Brechtian thinking through the song's empathetic power returns us to Gigi's key phrase on fleeing that animates the whole play. The flight is foretold by Miss Saigon's "logo" of the helicopters silhouetted by the sun, bright yellow against a wash of red. A cinematic trope made famous by Apocalypse Now (1979), Platoon (1986), and a long line of Vietnam War films, the chopper is the weapon of choice in the difficult terrain of the tropical jungle, ferrying American soldiers to the theater of war to hunt down the Viet Cong. Yet they also signal flight of the hunted, flying away to evacuate the wounded and to transport Americans and Vietnamese to safety, such as the infamous photograph of one of the last helicopters taking off from the US Embassy rooftop on 30 April 1975. The morphing of the hunter and the hunted crystalizes in the ambiguity of "flight" – to fly to one's prey or to fly away because one is the prey. The musical's helicopter logo epitomizes that paradox. Is the sun rising or setting at dawn or dusk? Is the chopper plunging into the battlefield or pulling out of one? Given the racist pidgin transposition of "r" and "l," that either-or conundrum bifurcates the operative word "flee" into its Orientalist and homophonic familiars of "free" and "flea." To flee to the land of the free is to become a flea, an unwanted refugee in America's body politic. To flee is driven by the urge to be free. Freedom, however, entails a wretched life of fleadom in a bipolarized, xenophobic, and refugee- and immigrant-averse MAGA Trumpland. From the musical's logo to the stage, Miss Saigon has long capitalized on the spectacle of a descending and ascending helicopter, deus ex machina on the crane, to ferry out soldiers. Figure 1 captures one of these hair-raising moments when the Vietnamese with documents in hand, Kim included, are barred by the Embassy gate. Crouching under the strong gale from the rotor blades and the deafening noise, the Vietnamese witness the vanishing of the promise made by the Promised Land as the helicopter rises, its beacon lights or headlights blinding like the Gorgon's gaze.

Figure 1

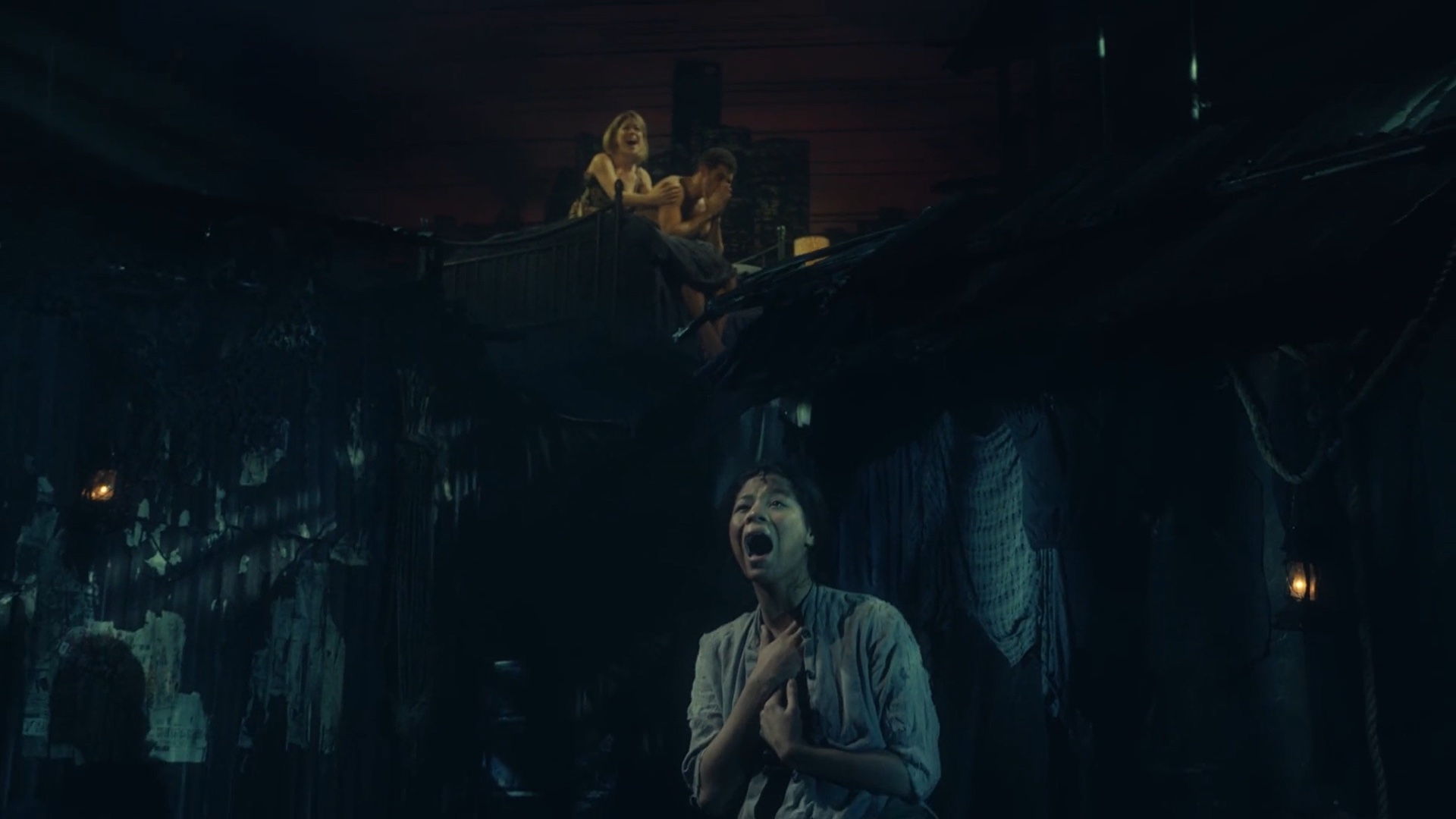

Figure 2

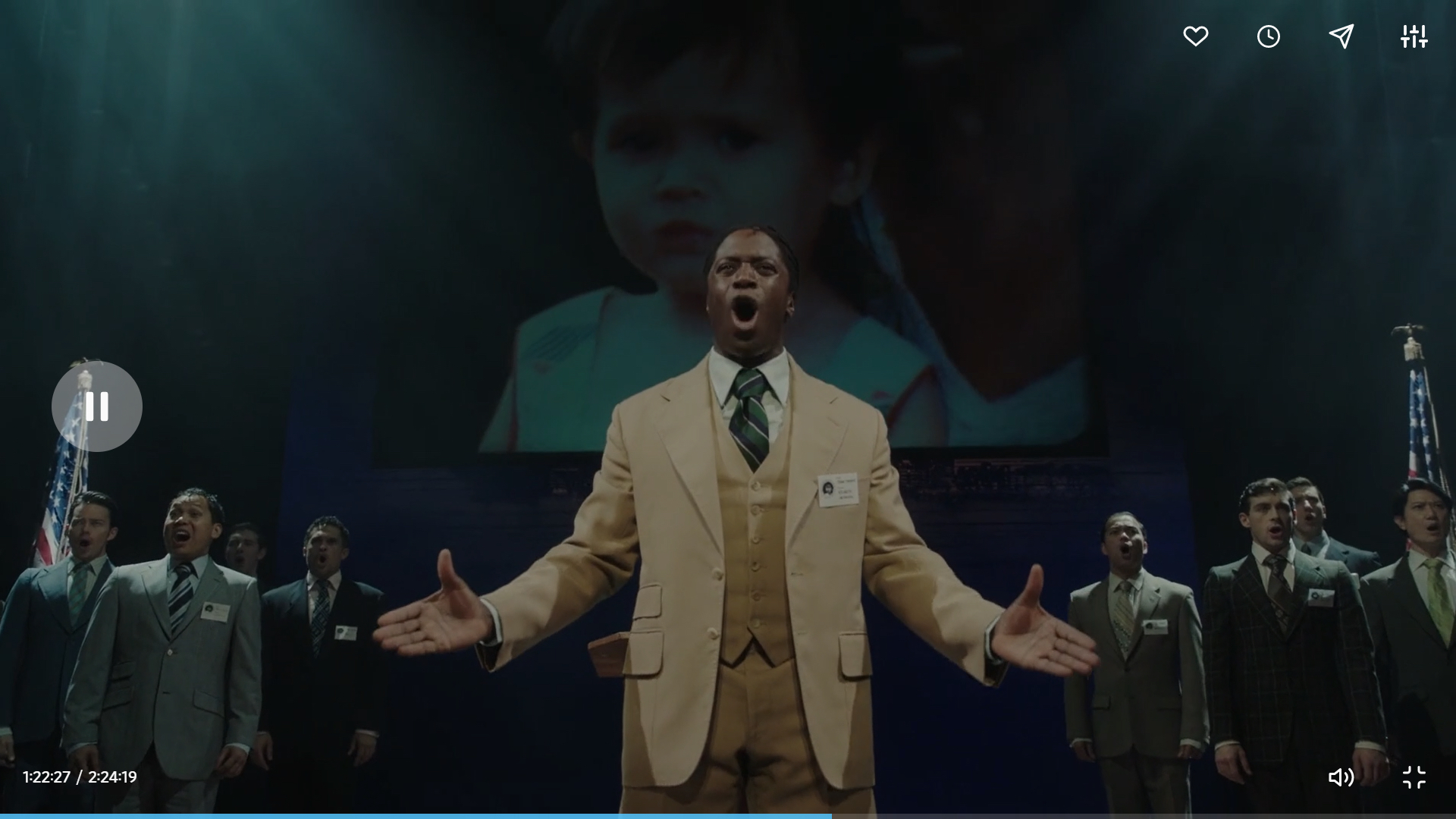

Filmic split screen is utilized through spatial division of the stage vis-a-vis an upper level aloft. Brechtian Alienation-effect comes into play for an empathetic dramatic theater entirely opposite to Brecht's intention in epic theater. Whereas Brecht's song and dance was designed to distance viewers emotionally, to prompt critical thinking and social action, West End and Broadway musicals comprise less dialogue and plot than trilling and emoting. Music seeks to move rather than to dissociate the audience. Lyricism and musicality do not digress from the plot; they constitute the plot. Filmic theme music and theme songs freeze the climax in poetry and musical notes, transcending, sublimating the prosaic dialogue and storyline. By contrast, Broadway musicals strive to stay midair, so to speak, on an elevated plane of emotional intensity, occasionally relaxing and lapsing into a spoken line or two, before characters break into song and dance all over again. Brecht is ill-advised to dispense of emotion, which, unequivocally, moves the audience. The seven character "e-motion," after all, is six-seventh "motion," should we do unto the English word what Ezra Pound did in dissecting Chinese ideograms as well as what Brecht himself did in abstracting and theorizing the female impersonator Mei Lanfang's Moscow performance in 1935. Although characters in Miss Saigon are largely one-dimensional, either innocent like Kim or depraved like the Engineer, John evolves somewhat throughout the play. He debuts in Dreamland in the stereotype of a black stud in dreadlocks, his barrel chest and torso bare under a sleeveless Army vest. John procures Kim at Dreamland for Chris, who 'thinks too much." Yet, John returns in Act 2 in a face-off of sorts, in suit and tie, hair closely cropped, presiding over a conference in the crusade on behalf of Amerasian children. Figure 6 shows John hitting the high note before a lectern and a screen of an apparently mixed-race Bui-Doi, “The dust of life / Conceived in Hell, / And born in strife.”

Figure 3

Even this doubling of Brechtian A-effect by means of song and the prop of a slideshow intensifies the affective power, not steering away from it. In a self-righteous manner, John's "hymn" around a "pulpit" lives up to the spectacle that musicals are destined to be, evolved from "Gilbert and Sullivan operettas of the late 19th century" to "its current form of Oscar Hammerstein and Jerome Kern's Show Boat in 1927" (Pao 24). Brechtian A-effect does work in a circuitous way in the cross-casting of Jonathan Pryce as the Engineer in London's run. Yoko Yoshikawa writes that "Pryce had been acting in yellow-face, with prosthetically altered eyelids and tinted makeup" (43). Angela Pao confirms the actor's facial makeup, complemented by Orientalist music: "On stage, Jonathan Pryce originally played the role using eye prosthetics and make-up, the traditional applications of Western theatre and film to signify Orientalness. His entrances are marked in the score by parallel musical signifiers, auditory caricatures of the tonalities characteristic of Asian musical forms" (33). Such Orientalist representations meander through Western dramas, from Brecht to Hare to Schönberg and Boublil, from the auteurist stage to the commercial one, from the performer's body to the spectator's mind. Long after the fall of Saigon, an Orientalist afterlife in millennial West arises still, loving and hating things Oriental simultaneously.

Notes 1. The age difference seems a recurring motif in David Hare's plays. Even in his mainstream BBC/PBS Johnny Worricker spy trilogy of the 2010s, that gap remains between Bill Nighy's Worricker and Rachel Weisz's Nancy Pierpan in Page Eight, but not so much between Nighy's and Helena Bonham Carter's characters in Salting the Battlefield. Carter plays, after all, Nighy's wife, unlike the love interest role for Weisz. 3. David Hare is well aware of the pushback to his ugly American Peggy, who offers a night of intimacy to whoever wins the debate between a young British idealist and a cynical Anglo-Indian novelist. In the Introduction to the collection of his plays The Secret Rapture and Other Plays (1997), Hare candidly describes to his interviewers, Faber and Faber editors, "the same hostility from the public" reported by three different actresses in Peggy's role when the play toured in Australia, England, and New York.

Works Cited Brecht, Bertolt. The Good Woman of Setzuan. 1947. U of Minnesota P, 1983. Freud, Sigmund. Beyond the Pleasure Principle. 1920. Translated by James Strachey, Norton, 1989. Hare, David. Saigon: Year of the Cat in The Secret Rapture and Other Plays. Grove Press, 1998, pp. 205-296. Keith, Jeffrey A. "Producing Miss Saigon: Imaginings, Realities, and the Sensual Geography of Saigon." Journal of American-East Asian Relations, vol. 22, no. 3, 2015, pp. 243–272. Loti, Pierre. Madame Chrysanthème. Calmann Lévy, 1895. Lu Hsun. Selected Stories of Lu Hsun. Translated by Yang Hsien-yi and Gladys Yang, Foreign Languages Press, 1960. Miss Saigon. Music by Claude-Michel Schönberg, lyrics by Alain Boublil and Richard Maltby Jr. 1989. H. Leonard Pub. Corp., 1991. Miss Saigon. 25th Anniversary Gala, performed live by Eva Maria Noblezada, Alistair Brammer, and Jon Jon Briones at Prince Edward Theatre, London, UK, 22 September 2014, https://www.dailymotion.com/video/x77vk1x Miss Saigon. Lyrics. https://www.allmusicals.com/m/misssaigon.htm Mitchell, David. The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet. Random House, 2010. Page Eight. Written and directed by David Hare, performances by Bill Nighy and Rachel Weisz, BBC/PBS Masterpiece Theatre, 2011. Pao, Angela. “The Eyes of the Storm: Gender, Genre and Cross-casting in Miss Saigon.” Text and Performance Quarterly, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 21-39. Saigon: Year of the Cat. Directed by Stephen Frears, performances by Judi Dench, Chic Murray, Yim Hoontrakul, Thames Television, BBC, 1983. Salting the Battlefield. Written and directed by David Hare, performances by Bill Nighy and Helena Bonham Carter, BBC/PBS Masterpiece Theatre, 2014. Turks and Caicos. Written and directed by David Hare, performances by Bill Nighy and Winona Ryder, BBC/PBS Masterpiece Theatre, 2014. Yoshikawa, Yoko. “The Heat Is On Miss Saigon Coalition: Organizing Across Race and Sexuality.” Loss: The Politics of Mourning, edited by David L. Eng and David Kazanjian, U of California P, 2003, pp. 41-56. |

Journal Home

AmericanPopularCulture.com