"A Hidden Race of Monstrous Beings":

Richard Wright's Revision

of H.P. Lovecraft's Ecological Horror

Americana: The Journal of American Popular Culture

(1900-present), Spring 2022, Volume 21, Issue 1

https://americanpopularculture.com/journal/articles/spring_2022/matzke.htm

Central Connecticut State University

|

In N.K. Jemisin’s The City We Became, a character who works at the Bronx art center rejects a painting that is inspired by the writing of H.P. Lovecraft because it reinforces Lovecraft’s bigoted view of racial others. She tells the artist, “I could see if you were trying to turn a mirror on Lovecraft. Show how twisted his fears and hatreds were” (148). This line serves as a kind of mission statement for the novel, which depicts a racially diverse coalition of characters coming together to defeat a Lovecraftian monster attempting to destroy New York City. Jemisin is one of a cohort of contemporary writers who turn a mirror on Lovecraft’s racism and engage with how that racism shapes some of the defining motifs of genre fiction. Victor LaValle’s The Ballad of Black Tom, Matt Ruff’s Lovecraft Country (and the HBO show it inspired), the films of Jordan Peele, and many other works have all revised elements of the Lovecraft mythos from explicitly antiracist positions. Ecological horror is central to that mythos. Much of the horror in Lovecraft’s fiction, and indeed much of the pulp fiction by his contemporaries, centers on natural disasters destroying familiar binaries – civilization vs. nature, mind vs. body. white vs. BIPOC. Today, pushing back against this sort of dualism is conventional wisdom among environmental justice advocates (see, for example, William Cronon’s canonical essay, “The Trouble with Wilderness”), and Brooks E. Hefner has recently identified how, at the same time that Lovecraft was publishing his stories, black pulp fiction writers were “reversing the pulp binaries of civilized and savage in a critique of Jim Crow segregation” (127). In this paper, I argue that another canonical writer may be understood as reconfiguring Lovecraftian ecological horror: Richard Wright. Set during the 1927 Mississippi River flood, Wright’s short story, “Down by the Riverside,” depicts the protagonist, a black farmer named Mann, attempting to escape the flood with his pregnant wife, but being conscripted to work on the failing levee. The story is illuminated through comparisons with several Lovecraft stories, particularly “The Whisperer in Darkness,” which is set in the aftermath of the Vermont flood of that same year, and “The Shadow over Innsmouth,” which depicts the internment of a small town’s residents after the discovery of an ecological horror. Considering these two writers alongside one another reveals a shared terror at the ways in which floods mark a change in humans’ relationship with the natural environment and a shared sensitivity to the implications that this change had for the construction of racial identity. For both authors, floodlands become sites of the gothic, as rising waters cause past horrors that were thought to be dead and buried to resurface: miscegenation and indigenous superstitions for Lovecraft, the specter of slavery for Wright. In order to consider how Wright, an avid reader of pulp magazines, revises Lovecraft’s ecological horror, I will first examine how pulp fiction shaped discourse around the 1927 Mississippi River flood. I will then explore flood motifs in Lovecraft’s fiction specifically, before turning to how Wright reworks these motifs in “Down by the Riverside” as well as his other flood story, “Silt.” This paper will argue that both authors employ the aesthetics of pulp horror to represent how a “civilized” notion of humanity, and specifically of whiteness, depended on the stability of a nature/civilization binary that the 1927 floods had revealed to be far more tenuous than previously assumed.

“The Mighty Old Dragon” The Mississippi river flood was not a purely “natural” disaster. Starting in the nineteenth century, the timber industry became an increasingly important part of the Mississippi river valley’s economy. As the Mississippi writer William Percy explained, “‘the litter on the forest floor, grasses, herbs, shrubs, rotting logs, twigs, leaves, flowers, even rocks and pebbles, all [retard] the runoff of the rains and snows’” (Chase 21). As widespread logging denuded the land, the watershed became increasingly vulnerable to floods. This trend accelerated in the twentieth century, aided by new industrial technologies of deforestation. For instance, one observer in the 1920s described the steam skidder as “‘an octopus of steel with several grappling arms running out 300 or more feet’ [that] dragged massive trees through the woods [and lay] ‘low everything in their way’” (Parrish 26). Viewed with this history in mind, the flood can be understood as a man-made phenomenon, a catastrophic failure of environmental engineering. It is important to note that the pulps are implicated in this catastrophe as well. The pulp magazine industry was born in 1896, when the publisher Frank Munsey decided to save money by printing his magazine, The Argosy, on inexpensive wood pulp paper, believing that readers would care more about the stories than the paper it was printed on (Collier). The paper was produced by pulverizing wood chips into small fibers, which are then bleached in a slurry of acid and pressed into large sheets. As magazine collector Ed Hulse describes, “Close examination of woodpulp paper will reveal tiny, embedded slivers of wood that weren't fully dissolved in the slurrying stage” (5). This inexpensive production process supported a booming magazine industry that flourished throughout the first half of the twentieth century, fostering a burgeoning print culture characterized by an expanding audience of readers. This expanding audience featured many young readers, working class readers, and readers of color, including, as we will see, a young Richard Wright. The natural/material conditions of papermaking cannot be disentangled from this new print culture – the pulp fiction industry both supported and was supported by the innovations that took place in the timber industry, and these innovations in turn had massive implications for both American literature and the Mississippi river. As Donna Haraway writes, “Flesh and signifier, bodies and words, stories and worlds: these are joined in naturecultures” (Companion Species 112). In the early twentieth century, the timber industry, the pulp fiction industry, and the Mississippi river were interconnected actors in an emergent natureculture. A sense of horror at the ecological transformations taking place in the Mississippi river valley is already suggested by the “octopus” metaphor used to describe the steam skidder. Writing in the 1930s about the grassland removal which, alongside logging, characterized the valley’s history, the economist Stuart Chase observed, “‘The natural grass cover had been torn to ribbons...the skin of America had been laid open’” (Parrish 27). Here we see the language of pulp fiction moving into journalistic and academic discourses, with industrial technology depicted as a monster and the land figured as that monster’s blood-and-gore-strewn victim. The spectacle of violence suggested by these metaphors is a common characteristic of the detective and true-crime genres, and the possible erotic subtext suggested by Chase’s image of skin being laid open evokes the pulp subgenre known as “shudder pulps,” which “portrayed innocent victims – often female – who were subjected to unbridled lust, torture, insanity, mutilation, and sometimes, mercifully, death” (Haining 131). Throughout the 1920s and 30s, popular but controversial shudder pulps like Terror Tales, Horror Stories, and Thrilling Mystery provided images of beautiful, scantily clad women being terrorized by “improbable villains with green skin or fleshless faces, monstrous limbs or deformed bodies” (Haining 143). In one such story, Terror Tales’ “Dance of the Bloodless Ones” (1937) by Francis James, vacationers are terrorized by “a hybrid monstrosity, half sea creature, half man” (108) (see Figure 1). As James describes it, "From the waist down the loathsome thing had in lieu of legs eight pinkish tentacles which writhed through the air like members of a multifold, living whip. Where they lashed and twined around the girl’s curving nudeness, jagged plashes of crimson blotched her skin" (108). Indeed, graphic descriptions of the creature’s victims fill the story: "Where cheeks and mouth had been was just raw and grisly pulp, through which the bones and white teeth gleamed in horrible outline. Some one – something – had ribboned that face with stripping of giant claws, literally cleaned off the flesh as though raked by a monstrous currycomb" (100-101).

Figure 1

The language of this story corresponds remarkably to language with which some writers commented on the ecological transformations around the Mississippi River, but it is important to note that this is but one example of a story formula that was repeated in dozens of magazines every month throughout the 1920s and 30s. Such images of eroticized violence were hardly new in the twentieth century, but the pulps constitute the locus of this sadomasochistic imagery in a cultural moment when it served the metaphorical purposes of writers like Chase in figuring the violence visited against a feminized mother nature. This horror imagery continues to appear in descriptions of the flood itself. The United States saw unusually heavy rainfall starting in late summer 1926, which continued through the winter of 1927 and began to undermine the Mississippi River levees in April. Commentators noted the human causes of the flood right from the beginning. For example, one noteworthy political cartoon published on April 27 depicts two giants pouring large buckets of water onto a mass of people in the Mississippi River valley, and the giants are labeled “Blind deforestation” and “Drainage of lakes and marshes." A sign beside the flooded masses reads “Denuded forest area” (see Figure 2). Nevertheless, many, particularly writers from the North, attempted to portray the flood as a battle of man against nature. These descriptions similarly show the language of the pulps creeping into journalistic accounts of the flood. A feature story in The New York Times, published on May 1, declared, “‘Once more war is on between the mighty old dragon that is the Mississippi River and his ancient enemy, man’” (Parrish 20). In this quotation, we get a competing vision of modernity, where nature, not industry, is the monster. Similar descriptions of the river appear in The Wall Street Journal and other national publications.

Figure 2

Figure 3

In July 1926, just as the the season of heavy rainfall was beginning, Lovecraft’s magazine Weird Tales published “Through the Vortex,” a Burroughs imitation by Donald Edward Keyhoe, in which a pilot is drawn into a mythic land of prehistoric beasts. Cover art for the story similarly features a male protagonist saving a damsel in distress from a mighty dragon (see Figure 4).

Figure 4

River/dragon versus steam skidder/octopus. What was at stake in these competing monster metaphors was an understanding of modernity itself: did the flood represent the failure of modern scientific rationalism, the limits of technocracy, and the fundamental untruth of narratives of “progress,” or could the flood become a part of those narratives and be figured as a war between ancient and modern? This was not only a question of environmental engineering, but also one of social engineering. Lower-income black communities bore the brunt of the effects of flooding throughout the disaster, and many black men were conscripted, often at gunpoint, to work on the failing levees. Different conceptions of what caused the flood informed different understandings of how to address it, as evidenced by conflicts between the Red Cross, an institution composed primarily of northern whites, and the Colored Advisory Commission, an institution made up of southern blacks, over how they defined “relief.” Susan Parrish writes, “For the Red Cross...restoration of the pre-flood status quo was the goal,” but the commission sought liberation from the unjust conditions that led to black communities’ chronic suffering, of which the flood was only the latest manifestation (42). This was a conflict over treating the symptoms vs. curing the disease, and in this respect, scientistic rhetorics around environmental stewardship overlap substantially with rhetorics around Jim Crow segregation.1 Black southerners understood that any attempt to enforce a boundary between nature and civilization would also involve excluding them from civilization.

“Things Found Floating in Some of the Swollen Rivers” In this light, it may be surprising that Lovecraft never directly wrote about the Mississippi River flood, but Lovecraft’s fiction is set almost exclusively in the region of New England from southern Vermont to his hometown of Providence, Rhode Island, and it is focused mainly on the fictional Miskatonic River Valley in northeastern Massachusetts, so much so that criticism and media inspired by the Lovecraft mythos often refers to this region as “Lovecraft Country.” One of the only Lovecraft tales to feature the Mississippi River valley is the globetrotting story, “The Call of Cthulu,” written in the summer of 1926 and published in Weird Tales in the summer of 1928. That story is set partially in St. Louis and states that Cthulu’s worshippers include practitioners of voodoo, described at various times as “mongrel Louisianans” and “swamp priests,” but it does not dwell on the region’s cultures or ecology (157, 150). Nevertheless, Lovecraft’s fiction contains numerous themes and motifs that can be placed in conversation with discourses around the Mississippi River flood, including a longstanding interest in how scientific rationalism fails in the face of – and may even bring about – ecological horror. For instance, in his story, “The Color Out of Space,” published in Amazing Stories in September 1927, a meteorite lands on the property of a farmer named Nahum Gardener. Three professors from the neighboring university arrive to investigate, but the meteorite shrinks and disappears, leaving them nothing to study. Abandoned by the scientific experts, increasingly bizarre phenomena occur around the Gardner place – crops and livestock die, snow melts more quickly there than anywhere else, and insects plague the family – all culminating in the Gardner family’s mysterious death. Though set in Lovecraft’s fictional town of Arkham, this story’s depiction of big city intellectuals’ indifference to rural people’s suffering echoes southerners’ critiques of flood management at the time. Lovecraft certainly would have been aware of the flood. He was a reader of The New York Times throughout the 1920s who both published and responded to advertisements in the paper and sometimes discussed news items in correspondence with friends (De Camp 209, 238, 297). Most notably, the Times was the first to announce the discovery of Pluto on March 14, 1930, while Lovecraft was writing “The Whisperer in Darkness,” about the fictional ninth planet Yuggoth. On March 15, Lovecraft wrote to his friend, the writer James F. Morton, “Whatcha thinka the NEW PLANET? HOT STUFF!!! It is probably Yuggoth” (Joshi and Schultz 298). Still, while Lovecraft followed the news, his fiction rarely explicitly addressed current events. “The Whisperer in Darkness” is an exception, not only for its depiction of a newly discovered ninth planet, but also for its invocation of the 1927 Vermont flood. Compared to the Mississippi River flood, the Vermont flood of that same year was dramatically different in character. As one commenter wrote, “‘The Mississippi Valley floods...were majestic demonstrations of vast volume and wide disaster [but] the New England flood was all over in a few hours of darkness and terror’” (Clifford 5-6). In forty-eight hours, the state was hit by what meteorologists described as “‘a cube of water more than a mile high, a mile long, and a mile broad’” (Clifford 4). And unlike the Mississippi Valley, where the waters broke the levees and stayed in a stagnant flood zone, sometimes for months, in Vermont the waters plowed through the steep valleys and left as soon as they came. Importantly, in a mountainous region without the context of poorly constructed levees and denuded forest lands, the Vermont flood could more easily be figured as an entirely natural disaster. Unlike in the Mississippi River flood, in the case of Vermont, humanity’s folly, implicitly, was not in its attempt to control nature, but in its failure to do so. This flood serves as the instigating incident for “The Whisperer in Darkness,” which was first published in Weird Tales in August 1931. As the narrator, a literature instructor and folklorist at Miskatonic University, describes, “Shortly after the flood, amidst various reports of hardship, suffering, and organized relief which filled the press, there appeared certain odd stories of things found floating in some of the swollen rivers” (200). These strange “organic shapes,” though vaguely human, are neither human nor animal. Lovecraft’s description of this monstrous detritus has its origins in history; news of both the Vermont and Mississippi floods carried vivid descriptions of drowned livestock rotting after the waters had receded. As the Manchester Guardian put it in July 1927, reporting on the Mississippi flood, “Here and there, half submerged in slime and mud, are the decaying bodies of farm animals, poisoning the air with their stench” (Parrish 47). In Lovecraft’s story, debate over the nature of these dead things leads to the suggestion that they are “a hidden race of monstrous beings,” and the narrator surveys several accounts of such beings from folklore, stating, “the Indians had the most fantastic theories of all” (202, 204). This debate leads the narrator to befriend Henry Wentworth Akeley, a local man who believes the bodies are those of space aliens with whom he has had contact. The story suggests that these aliens are “the old ones,” the demonic prehistoric extraterrestrials that recur throughout the Lovecraft mythos. The story concludes with the implication that the old ones have surgically removed Akeley’s brain and placed it in a machine so that he may travel through space. In this progression from the flood to Akeley’s transformation, the story combines two major Lovecraftian motifs, thalassophobia (fear of bodies of water, and especially of sea monsters) and horror at the loss of humanity (which implicitly depends on embodiment). This loss of bodily autonomy is here, as it often is in Lovecraft’s work, figured in racial terms – by consenting to the surgery, Akeley loses his face, his whiteness, and becomes a whisperer in darkness, a transgression on par with miscegenation.2 These themes of ecological horror and miscegenation appear in The Shadow over Innsmouth as well. This novella was written in 1931 and published in 1936, but Lovecraft sets the story in July of 1927, just as flood relief efforts were under way in the Mississippi River delta (269). The story depicts the narrator’s discovery that the families in the fictional town of Innsmouth are products of interbreeding between humans and the amphibious “deep ones.” Unlike the sea monster hybrid in “Dance of the Bloodless Ones” (who is eventually revealed to be a man in a suit), the townsfolk of Innsmouth are not outwardly monstrous, merely “queer” and “other-worldly” in their behavior and appearance, with skin that “ain’t quite right” (272, 276, 273). Again, descriptions of wetness and rotting stenches parallel accounts of the floods, but what is most striking is the story’s framing. The story begins with the narrator’s description of the federal government’s actions in Innsmouth before flashing back to his account of his discovery, which led to those actions. These opening descriptions seem straight out of accounts of the government’s management of the Mississippi River flood:

Both S.T. Joshi’s The Call of Cthulhu and Other Weird Stories and Leslie S. Klinger’s The New Annotated H.P. Lovecraft include a note with this line, clarifying that Lovecraft’s invocation of concentration camps does not refer to Nazi concentration camps, which were not created until 1933, and explaining that concentration camps date back to the Boer War in the late nineteenth century (Joshi 411; Klinger 574). Neither Joshi nor Klinger, however, note a more recent use of the term: in 1927, the Red Cross established 149 camps, which they called “concentration camps,” along the Mississippi River delta (Parrish 41). These camps had “325,554 people living on-site and an almost equal number being provided for outside the camps” (Parrish 41). The National Guard brought the largely African- American population of flood refugees to these camps and forced many of them to work on the failing levees (Parrish 8). In this passage from The Shadow over Innsmouth, then, we see Lovecraft rewriting the very real horrors of disease, concentration camps, and prisons that characterized the government’s response to the crisis, and recasting them as justified in the face of an unprecedented threat; namely, the threat of mixing with alien others. The story makes the connection between interbreeding with the deep ones and miscegenation explicit early on, when the narrator speaks with a ticket agent, who tells him:

Strikingly, in the space of one monologue, the ticket agent condemns both globalism and provincialism, implying that the problem with Innsmouth stems from the fact that they “brought back” “queer kinds of people” from other parts of the world while also being geographically “cut off” from the rest of the country. Unlike the framing passage about concentration camps, which was added later, this passage survived from a discarded early draft of the story, suggesting its centrality (Lovecraft “Discarded Draft” 61). If this initial implication of interracial mixing sets the tone for the story, the revelation of interspecies mixing constitutes an amplification of that transgression. Concentration camps become justified as a means of containing these chimera and protecting the purity of the (white) human race.

“The Wet, Blurred Green” In these stories, Lovecraft exemplifies precisely the mentalities that Richard Wright responds to in “Silt” and “Down by the Riverside,” including fear of racial mixing, privileging of northern experiences over southern ones, and justification for concentration camps. At the same time that Lovecraft was writing and publishing these stories, Wright was in his teens and early twenties, growing up in Memphis – which was a major hub for flood relief efforts in 1927 – before moving to Chicago near the end of that year. Wright’s roots in pulp fiction run deep. In his autobiography, Black Boy, Wright describes reading “tattered, second-hand copies of Flynn’s Detective Weekly or the Argosy All-Story Magazine” (156).3 He goes into vivid, nostalgic detail about these childhood reading experiences: "I would go to my room and lock the door and revel in outlandish exploits of outlandish men in faraway, outlandish cities…. The cheap pulp tales enlarged my knowledge of the world more than anything I had encountered so far. To me, with my roundhouse, saloon-door, and river-levee background, they were revolutionary, my gateway to the world" (151). Wright’s repeated use of the word “outlandish” here takes on a double meaning, establishing a relationship between the romantic or fantastic genre conventions of the pulps and their ability to transport him beyond his insular Mississippi Delta upbringing – the stories are literally out of the land where he lives. In Wright’s characterization of his youthful reading practices, the pulps appear both anti-realist and more realistic, both contrary to his lived experience and doubtlessly authentic. Wright recognizes the contradiction in his childhood interpretations: “I accepted them [the pulp stories] as true because I wanted to believe them” (151). Tellingly, when contrasting the outlandish pulps with his provincial reality, Wright specifically points to his proximity to river levees, placing pulp fiction’s sensationalism outside of the local environment and, implicitly, the Mississippi River flood. Much of Wright’s work attempts to reconcile this contradiction by marrying a pulp style to themes of environmental racism, and this is evidenced in Uncle Tom’s Children, the collection in which Wright published “Down by the Riverside.” That marriage is made problematic by the relationship between pulp fiction and white supremacy that writers like Lovecraft often evince. In Black Boy, Wright describes becoming aware of this relationship at an early age. When Wright was around thirteen or fourteen years old, he took a job selling newspapers so that he could read the fiction in the paper’s magazine supplement, such as Zane Grey’s Riders of the Purple Sage, but he quit the job in disgust after learning that the paper was a Ku Klux Klan publication. Still, those pulp influences comprise a major component of his fiction. As Paula Rabinowitz asserts, “A close reader of trash, from his earliest exposure to pulp magazines, [Wright] deployed what he had learned in his novels and essays” (85). And while Rabinowitz focuses on Wright’s relationship with crime fiction, his works show the influence of pulp horror as well. Indeed, in the scene in Black Boy when a black man explains to the young Wright that the newspaper is a white supremacist publication, before he understands what the man is saying, Wright describes his impatience: “I waited, annoyed, eager to be gone on my rounds so that I could have time to get home and lie in bed and read the next installment of a thrilling horror story” (152). Horror fiction specifically, rather than detective fiction or western fiction, is the genre with which Wright associates his discovery of pulp fiction’s racism. As J.M. Tyree writes, describing this scene in Black Boy, "There is no reason to suspect that Wright was reading H. P. Lovecraft…. But Wright's sense of shock and recognition when the awful truth dawns on him parallels the feelings many readers have when they discover the racism that manifests itself in Edgar Allan Poe or Lovecraft" (137). While it is unlikely that Lovecraft wrote the “thrilling horror story” to which the young Wright was eager to return, it is entirely possible that Wright did read Lovecraft at some point. Jet magazine even wrote that the title for Wright’s 1954 novel Savage Holiday came from a Lovecraft story (Fabre 605). However, the phrase “savage holiday” does not appear in Lovecraft’s corpus, and it is possible that Savage Holiday was confused with The Outsider, the novel that Wright had published the previous year, which shares its title with a very famous Lovecraft story from 1926, which was also the title of Lovecraft’s first published collection (Walker). In any case, Lovecraft does constitute a significant figure in the cultural ferment out of which Wright’s pulp aesthetic arises, just as commentaries about the Mississippi River flood constitute a significant part of the cultural ferment out of which Lovecraft’s pulp aesthetic arises. In Wright’s stories about the flood, he can be seen as taking up Lovecraftian motifs and flipping the racial implications of those motifs on their head.4 The gothic attributes of the flood come out strongly in his short story, “Silt,” published in the August 24, 1937 issue of The New Masses and reprinted as “The Man Who Saw the Flood” in Wright’s 1961 collection, Eight Men. More of a vignette than a story, “Silt” features a family returning to their home after the waters have receded, surveying the damage, and realizing that it will place them deeper into debt with their white landlord and creditor (they are presumably sharecroppers). Wright describes the scene early on: “Over all hung a first-day strangeness” (19). When the family enters the cabin, he writes that it “looked weird, as though a ghost were standing beside it” (19). In these invocations of weirdness and first-day strangeness (implying more uncanny experiences yet to come), Wright calls on the tradition of the weird tale as Lovecraft defines it in his essay, “Supernatural Horror in Literature”: “A certain atmosphere of breathless and unexplainable dread of outer, unknown forces must be present; and there must be a hint, expressed with a seriousness and portentousness becoming its subject” (15). Wright follows these invocations of weirdness with vivid sensory details:

Here the cabin is personified through a series of similes connoting death and disaster: "like a bloated corpse," "like a casket," "as though huddled together." While the flood left plenty of actual decaying animal corpses in its wake, Wright displaces images of putrefaction onto the home. Doing so renders the scene frighteningly uncanny: death is so pervasive that even inanimate objects are decomposing. Lovecraft appreciated a decomposition simile as well; nearly as many “corpse-like” things appear in his stories as actual corpses, often associated with water, even when the story takes place entirely on land. In “The Rats in the Walls,” for instance, Lovecraft describes the scurrying sounds of rats “rising, as a stiff bloated corpse gently rises above an oily river that flows under endless onyx bridges to a black, putrid sea” (108). For both Lovecraft and Wright, literal and metaphorical decomposition coexist because everything rots beneath rising waters. Like “Silt,” Wright’s “Down by the Riverside” was written in 1937 and begins with a similar image of a home decomposing: “Each step he took made the old house creak as though the earth beneath the foundations were soggy” (62). Here Wright’s use of the simile, “as though,” is ironic, as the earth beneath the foundation is literally soggy. The decomposition imagery runs through this opening paragraph as the protagonist, a farmer named Mann, observes his house – “He walked to the window and the half-rotten planks sagged under his feet” (62) – and the fields outside – “All the seeds for spring planting were wet now. They gonna rot, he thought with despair” (62). From this gothic beginning, we learn that Mann is trying to get a boat so that he and his wife, who has been in labor for four days, can get to the Red Cross hospital in town. Water is six feet high and rising. He accepts a boat that a friend has stolen from a white man, only to encounter that same white man as they make their way to the hospital. Recognizing his boat, the white man tries to shoot Mann, and Mann returns fire in self-defense, killing him. They travel on, but Mann’s wife and unborn child die after they are detained by National Guardsmen. He is then conscripted to work on the levee, only to see it break in front of him. He is then told to go rescue a trapped family, which turns out to be the wife and son of the man he killed. The boy recognizes Mann, who is taken away by the National Guardsmen to be shot. Mann runs and is gunned down; as Wright describes it, “ Bullets hit his side, his back, his head. He fell, his face buried in the wet, blurred green” (123). Wright’s flood stories have several motifs in common with Lovecraft, in addition to the aforementioned images of rot and putrefaction. For both writers, character names suggest allegory and historical commentary. As Parrish writes, "Characters in his [Wright’s] flood fiction – 'Heartfield,' 'Mann,' 'Burgess,' and 'Burrows' – draw into the orbit of the story the wider intellectual and geographic worlds of the Dadaist Heartfield, the sociologists Delbert Mann and Ernest Burgess, and the psychologist Trigant Burrow" (245). These names suggest the artistic and intellectual traditions to which Wright is responding; as Parrish notes, the work of sociologists like Delbert Mann and Stuart Queen paints a rather optimistic picture of societies’ responses to disasters, asserting that they bring about a “‘realignment of social forces which will make for a better organized community working more effectively toward the solution of its various problems’” (Parrish 253). The 1927 flood, as the experience of Wright’s Mann shows, gives the lie to this picture. Mann’s name also, unavoidably, carries broader allegorical implications, and it is easy to see Mann as carrying on in the tradition of Piers Plowman and Young Goodman Brown, taking a journey through a flooded wilderness with the goal of finding salvation through the cross – in this case, the Red Cross. Mann, however, is unable to arrive at that salvation; the negro spiritual to which the story’s title alludes depicts the river as a site of baptism, but when Mann is shot his body falls and “stopped about a foot from the water’s edge” (124). Lovecraft’s attitude towards the possibility of salvation is similarly bleak, as in “The Color Out of Space.” Certain elements of the story easily suggest that the piece serves as an allegory for the Fall, with the protagonist, a farmer whose last name is Gardner and whose first name, Nahum, is an anagram for “human,” eating the fruit of knowledge in the form of his own poisoned crops and well water. But ultimately, “The Colour Out of Space” is not a story about the corrupting influence of knowledge so much as it is about the failure of knowledge, or, more precisely, the failure of modern science, as the experts all abandon the Gardeners without offering solutions. The narrator hints at bitterness over this abandonment near the story’s end: “The rural tales are queer. They might be even queerer if city men and college chemists could be interested enough to analyse the water from that disused well, or the grey dust that no wind seems ever to disperse” (197). For both Lovecraft and Wright, ignorance is the source of tragedy; as Parrish writes about “Down by the Riverside,” “Wright had fashioned in Mann an experiment, acted out in something like real time, in letting knowledge of risk slip out of your hands and your memory” (276). Both Mann and Nahum Gardener are positioned not simply as rural farmers but as allegorical everymen facing massive forces of nature without institutional support or the necessary knowledge of how to manage risk. For both writers, managing risk necessitates navigational knowledge, as the greatest horrors stem from trespassing into racial others’ spaces. In his xenophobic tale, “The Horror at Red Hook” (1927), Lovecraft introduces the horrors that will befall his detective protagonist due to immigrant occultists by asking:

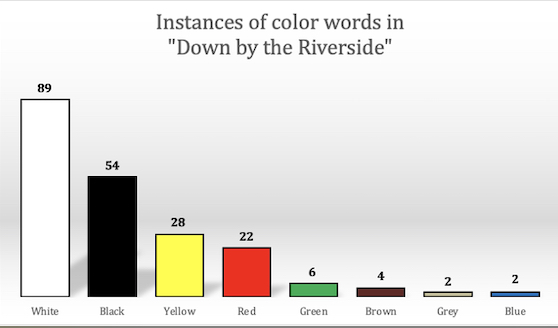

For Wright, rhetorical questions similarly signal confusion as to how his protagonist should navigate a multiracial space as Mann asks himself, “Mabbe Ahm headin the wrong way? […] Wondah whose house is tha? Is they white folks?” (76-77). Both writers’ constructions of fear are based on tense interactions with racial others, but Wright turns that fear on its head by figuring whites as the other. For example, when Mann encounters two white soldiers, Wright describes his difficulty seeing them through the glare of their lights: “Their faces were like square blocks of red” (83). Catherine Gooch notes that Wright “goes out of his way to explicitly humanize Mann” (20), and here we can see that, as a corollary, Wright goes out of his way to figure whites as not fully human, and sometimes as monstrous. This contrasts with Lovecraft’s protagonists, who occupy a racially heterogeneous world in which whiteness is figured as the default and nonwhites are racially marked. This motif is best exemplified by Lovecraft’s frequent references to Abdul Alhazred, author of the Necronomicon, as “the mad Arab” (“The Whisperer in Darkness” 214, for example). However, Wright does not simply reverse this motif, marking whiteness and leaving blackness unmarked. Indeed, in the opening line of “Silt,” the family is introduced as “a black father, a black mother, and a black child” (19). In this way, the story’s opening line creates a tension, giving the characters a universality by identifying them by their family roles, but simultaneously marking them off with the repetition of “black.” Both “Silt” and “Down by the Riverside” mark both black and white characters’ races with noteworthy frequency, but in a sense these invocations of “black” and “white” are only part of a broader focus on color imagery. In the 16,981 word story, “Down by the Riverside,” color words appear 207 times, comprising more than 1.2% of the words in the entire story (see Figure 5). “Black” and “white” – often used to describe a character’s race – appear the most often, followed by “yellow” (often used to describe the color of the water or a light source) and “red” (often used in the phrase “Red Cross”). “Green” appears only six times in the story, but four of those instances occur in the last page; when the guardsmen are escorting Mann to be shot, one lights a cigarette and “A smoking match flicked past his eyes and hit waves of green, wet grass” (123). When Mann decides to run, “His shoes slipped over waves of green grass…. He left the hazy trees and ran in the open over waves of green” (123). And when he is shot, “He fell, his face buried in the wet, blurred green” (123). Through this repetition, Wright creates an association between the green of the grass and death, subverting the common use of green as a symbol for life.

Figure 5

Uncle Tom’s Children is invested in the power of green as a symbol for danger; in his essay, “The Ethics of Living Jim Crow,” which introduces the collection, Wright describes growing up in the rural South and observing that green spaces could only be found in white neighborhoods. Catherine Gooch notes that Wright’s observations exemplify what she calls “the Black pastoral”: "Because Black Americans have never been able to move freely through rural or pastoral lands, our affective ties to that landscape are inherently limited and complicated by a long racialized environmental history...for Black Americans, the idyllic notion of the pastoral is inaccessible" (3-4). By observing how the land is shaped, used, and colored, Wright explains the association between greenness and whiteness that he formed as a child. Furthermore, he shows that the picturesque landscapes of the American South are not natural, but rather the products of ecological transformation that took place under systems of white supremacy, and that continue to enforce both social and environmental segregation.5 This is perhaps the most powerful thematic correspondence between Wright and Lovecraft, their sense of fear arising from stories that disrupt comfortable understandings of the nature/civilization binary. The entire arc of “The Whisperer in Darkness,” from the discovery of the strange corpses in the aftermath of the flood to Akeley’s horrific transformation, constitutes an escalating series of moments where the line between the natural and the artificial becomes blurred. “The Colour Out of Space” enacts this same blurring by defamiliarizing readers not simply from nature, but from color itself. As Lovecraft puts it, the indescribably strange color of the meteorite spreads, infecting the local flora, implying that the events of the story constitute the opening episode of an ecological disaster brought on by either an invasive species or a deliberate act of terraforming (198). Nahum’s deathbed monologue gives a sense of the color’s ineffable weirdness: “Nothin’…nothin’…the colour…it burns…cold an’ wet…but it burns…it lived in the well…I seen it…a kind o’ smoke…jest like the flowers last spring…the well shone at night…Thad an’ Mernie an’ Zenas…everything alive…suckin’ the life out of everything…” (188, ellipses in original). Lovecraft’s use of ellipses underscore Nahum’s struggle to describe the indescribable, and to the strangeness of the color is added a contradictory sensory experience, that a substance can feel cold and wet but also burn. For both Lovecraft and Wright, fear stems from the breakdown of divisions – colors that cannot be categorized, hierarchies that cannot be maintained. For Lovecraft, this is a tragedy, and he longs for scientists or concentration camps that can restore order. But Wright’s characters never had access to that order to begin with. The disaster has given the lie to categories that only ever served to uphold white supremacy, and the blurring of the green serves as a reminder that the nature/civilization binary is false.

Wright and Lovecraft in the Chthulucene I note these correspondences not to imply any direct line of influence between Lovecraft and Wright, but merely to confirm the affinities between the two authors that both informs an historical understanding of the 1927 floods and provides a set of motifs with which to understand the mentalities underlying environmental racism and white supremacy more broadly. Contemporary genre fiction that wrestles with Lovecraft explores many of the same themes as Wright’s flood stories. For example, by plunging some of the writers of the Safe Negro Travel Guide into a Lovecraftian world, Matt Ruff’s Lovecraft Country comments on the ability of black Americans to navigate white spaces in ways that mirror the navigational themes in “Down by the Riverside.” And by retelling “The Horror at Red Hook” from a black man’s perspective, Victor LaValle casts the xenophobic tale of Detective Malone in a new light, highlighting the intersections of white supremacy and state violence in a way that not only speaks to the Black Lives Matter movement’s protests against police brutality, but that also echoes Wright’s depiction of the National Guard. These examples show that Lovecraft created a mythopoetics with which discourses around environmental justice can be figured. Nearly a century after the Mississippi River flood, these mythopoetics have only gained relevance as incidents such as the Flint water crisis and the Standing Rock protests have amplified fears around finding “things…floating in some of the swollen rivers,” and have increased awareness of how such fears are tied to segregation and environmental racism. Donna Haraway has asserted that our dominant cultural narrative, that of the anthropocene, is inadequate to address our current challenges surrounding environmental justice and has posed the “Chthulhucene” as an alternative that decenters humans in favor of “rich multispecies assemblages” (Staying with the Trouble 101). In coining this term, Haraway disavows Lovecraft’s influence:

Haraway attempts to connect her mythopoetics to the ancient beliefs of indigenous cultures, but of course Lovecraft’s old gods loom large in contemporary culture, and the association is difficult to refute. By naming our current geological epoch the Chthulhucene, she is not so much doing away with the Lovecraft mythos as revising it, confronting fundamentally similar cosmic horrors of death and environmental catastrophe, but choosing to embrace rather than recoil at “tentacular” ways of being and thinking. I want to suggest that, like the works of Jemisin, Ruff, LaValle, and Haraway, Richard Wright’s flood stories can be seen as a revision of Lovecraft, one that approaches ecological horror from a radically different perspective and arrives at radically different conclusions. Examining the congruities between these two authors reveals some of the cultural myths that need to be reimagined in the fight for environmental justice. Only through such reimagining can the hidden race cease to be monstrous and the blurred green cease to be tragic.

Notes 1. As Catherine Gooch puts it, writing about “Down by the Riverside,” “The short story’s focus on the natural disaster...suggests that the natural environment is inextricable from the daily Jim Crow social environment” (12). 2. Brooks E. Hefner notes that “the white mind/Black body dichotomy” is a familiar trope in horror fiction that Black horror stories have critiqued from Cora Moten’s “The Creeping Thing” in 1929 through Jordan Peele’s Get Out in 2017 (43). 3. According to Toru Kiuchi and Yoshinobu Hakutani, Wright had subscriptions to these two weekly magazines from January 1922 until the summer of 1926 (24-29). Neither of these magazines ever published fiction by Lovecraft, but it is uncertain what other pulp fiction Wright may have read. 4. It is worth noting that other motifs from sci-fi/horror serve as structuring images through which to understand racism in several of Wright’s works. In a significant episode in The Outsider, Damon Cross listens to several other characters debate a conspiracy theory that flying saucers have landed on earth, and white men have hidden the news of them because the aliens are colored men (33-35). And in the essay “Memories of my Grandmother," Wright describes the film The Invisible Man as a key influence on his novel The Man Who Lived Underground (177-178). 5. Parrish notes how Wright develops these themes in that concluding scene from “Down by the Riverside": “If, in ‘Ethics,’ the green landscape was a ‘symbol of fear’ (3), here, as Mann lies, with ‘his face buried in the wet, blurred green’ (123), the symbol is realized” (270).

Works Cited Burroughs, Edgar Rice. At the Earth’s Core. A.C. McClurg, 1922, http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/545. Chase, Stuart. Rich Land, Poor Land: A Study of Waste in the Natural Resources of America. Whittlesey House, 1936. Clifford, Deborah Pickman, and Nicholas R. Clifford. “The Troubled Roar of the Waters”: Vermont in Flood and Recovery, 1927-1931. U of New Hampshire P, 2007. Collier, Beau. “So What Is Pulp?: A Brief Material History of American Pulp Magazines.” The Pulp Magazines Project, 2011, https://www.pulpmags.org/contexts/essays/what-is-pulp-anyway.html. Cronon, William. “The Trouble with Wilderness; or, Getting Back to the Wrong Nature.” Uncommon Ground: Rethinking the Human Place in Nature, edited by William Cronon, W. W. Norton & Co., 1995, pp. 69-90. Darling, Jay N. “Ding.” Relieve the Flood Sufferers, but the Cure Lies at the Other End. 27 Apr. 1927, https://digital.lib.uiowa.edu/islandora/object/ui%3Ading_3306. The University of Iowa Libraries. De Camp, L. Sprague. H.P. Lovecraft: A Biography. Barnes & Noble, 1996. Fabre, Michel. The Unfinished Quest of Richard Wright. Morrow, 1973. Gooch, Catherine D. “Death by the Riverside: Richard Wright’s Black Pastoral and the Mississippi Flood of 1927.” ISLE: Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment, Nov. 2020, pp. 1-23, doi:10.1093/isle/isaa190. Haining, Peter. The Classic Era of American Pulp Magazines. Chicago Review Press, 2001. Haraway, Donna. The Companion Species Manifesto: Dogs, People, and Significant Otherness. Prickly Paradigm Press, 2003. ---. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Duke UP , 2016. Hefner, Brooks E. Black Pulp: Genre Fiction in the Shadow of Jim Crow. U of Minnesota P, 2021. Hulse, Ed. The Blood 'n' Thunder Guide to Collecting Pulps. Murania Press, 2009. James, Francis. “Dance of the Bloodless Ones.” Terror Tales, July 1937, pp. 98-120. Luminist Archives. https://s3.us-west-1.wasabisys.com/luminist/PU/TT_1937_07.pdf. Jemisin, N. K. The City We Became. Orbit, 2021. Joshi, S. T., and David E. Schultz. An H.P. Lovecraft Encyclopedia. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2001. Kiuchi, Toru, and Yoshinobu Hakutani. Richard Wright: A Documented Chronology, 1908-1960. McFarland & Company, 2013. LaValle, Victor. The Ballad of Black Tom. Tordotcom, 2016. Lovecraft, H. P. “Discarded Draft of ‘The Shadow Over Innsmouth.’” Miscellaneous Writings, edited by S.T. Joshi, 1st edition, Arkham House Pub, 1995, pp. 59-65. ---. Supernatural Horror in Literature. Dover Publications, Inc., 1973. ---. The Call of Cthulhu and Other Weird Stories. Edited by S.T. Joshi, Penguin Books Ltd, 2011. ---. “The Color Out of Space.” The Call of Cthulhu and Other Weird Stories, edited by S.T. Joshi, Penguin Books, 1999, pp. 170-99. ---. “The Horror at Red Hook.” The Dreams in the Witch House and Other Weird Stories, edited by S.T. Joshi, Penguin Books, 2004, pp. 116-37. ---. The New Annotated H.P. Lovecraft. Edited by Leslie S. Klinger, annotated edition, Liveright, 2014. ---. “The Outsider.” The Call of Cthulhu and Other Weird Stories, edited by S.T. Joshi, Penguin Books, 1999, pp. 43-49. ---. “The Shadow Over Innsmouth.” The Call of Cthulhu and Other Weird Stories, edited by S.T. Joshi, Penguin Books, 1999, pp. 268-335. ---. “The Whisperer in Darkness.” The Call of Cthulhu and Other Weird Stories, edited by S.T. Joshi, Penguin Books, 1999, pp. 200-67. Parrish, Susan Scott. The Flood Year 1927: A Cultural History. Princeton UP , 2017. Rabinowitz, Paula. American Pulp: How Paperbacks Brought Modernism to Main Street. Princeton UP , 2014. Ruff, Matt. Lovecraft Country. Reprint edition, Harper Perennial, 2017. St. John, J. Allen. Dust-Jacket Illustration for At the Earth’s Core by Edgar Rice Burroughs. 1922, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:At_the_Earths_Core_1922_Dusk_Jacket.jpg. Wikimedia Commons. Stevenson, E. M. Cover for Weird Tales. 1 July 1926, Tyree, J. M. “Lovecraft at the Automat.” New England Review (1990-), vol. 29, no. 1, 2008, pp. 137-50, https://www.jstor.org/stable/40245072. Walker, Steve. The Limbonaut XLVI: A Correlation of Lovecraftian Contents on the Web. 2008, https://library.ucmo.edu/faculty/walker/limbonaut_46.htm. Wright, Richard. Black Boy: (American Hunger): A Record of Childhood and Youth. HarperPerennial Modern Classics, 2006. ---. “Down by the Riverside.” Uncle Tom’s Children, HarperPerennial, 2004, pp. 62-124. ---. Eight Men. HarperPerennial Modern Classics, 2008. ---. “Memories of My Grandmother.” The Man Who Lived Underground, First, Libray of America, 2021, pp. 161-212. ---. “Silt.” The New Masses, Aug. 1937, pp. 19-20, https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1937/v24n09-aug-24-1937-NM.pdf. ---. “The Ethics of Living Jim Crow.” Uncle Tom’s Children, HarperPerennial, 2004, pp. 1-15. ---. The Outsider. Perennial, 2003.

|

Journal Home

AmericanPopularCulture.com