The Rise, Definition, and Classification

of Self-Help Literature

Americana: The Journal of American Popular Culture

(1900-present), Spring 2023, Volume 22, Issue 1

https://americanpopularculture.com/journal/articles/spring_2023/alharbi.htm

King Saud University

|

Introduction

The term "self-help" has been around for longer than might be expected. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, this term was first used in the 1830s to refer to the self-initiated practice of pursuing lawful means in order to redress a wrongful act. Since then, however, it has acquired new meanings, which often do not align with one another. In economics, for example, it is used to describe a country's movement towards economic self-sufficiency (see Madsen) whereas, in education, it picks up a different meaning, referring to self-access learning materials and resources (see Effing). Within the field of psychology, the term self-help has taken even more varied forms, ranging from individual self-care to mutual-aid groups (see Moody). It is clear from this discussion that the term has been understood and applied differently in different contexts. As a distinct genre of popular nonfiction, a clear definition and classification system is long overdue. Steven Starker, like others (see Douglas; Effing), traces the roots of self-help literature back as far as eighteenth-century America, a period which marked an end to British rule, thereby paving the way for upward social mobility among Americans of lower socio-economic status. According to Starker, self-help was espoused as a new conception of society modeled on what later became known in American ideology as the "pursuit of happiness," first articulated in Thomas Jefferson's Declaration of Independence of 1776, which reads, "We hold these truths to be sacred and undeniable; that all men are created equal and independent, that from that equal creation they derive rights inherent and inalienable, among which are the preservation of life and liberty and the pursuit of happiness." Beth Blum, in her recent book The Self-Help Compulsion, offers a different view about the origins of self-help discourse. She insists, instead, that it emerged "out of the Victorian working-class" in Great Britain (Blum 3). Such a claim does not seem to withstand exposure to historical scrutiny, as there is extensive evidence in support of the origin of self-help literature as a distinctive aspect of American cultural identity since the birth of the nation. Helen Anne Douglas, for example, demonstrates how self-help literature was rooted in American religious literature authored by such men as Reverand Michael Wigglesworth inspired by his "Calvinist theology" as early as 1662 (15). She further explains that there were three main factors contributing to the emergence of this form of literature in early American culture. These were the impact of urbanization, the rise of the middle class, and the popularization of psychology. Douglas posits that America's transition to an industrial economy triggered the need for self-help manuals to equip urban dwellers – particularly those coming from rural areas – with appropriate behavioral skills to get along with other people (18). She added that the rapid expansion of the middle class was another major factor that gave rise to the need for self-help literature (Douglas 22). This time, however, the emphasis was not on rules of living but rather on the pursuit of success and the accumulation of wealth (Douglas 26). Lastly, she argues that the increased demands of industrialization affected the lives of middle-class Americans, causing so many of them to turn to popular psychology in search of solutions to accommodate these demands (Douglas 28). By the second half of the nineteenth century, self-help was purportedly first recognized as a distinct genre in its own right, in particular with the publication of Samuel Smiles's Self-Help. This book is widely believed to have provided the genre with its very name. “Smiles not only coined the name of the genre, Self Help,” says Robin Ince, “he also set the tone for what it might do to the publishing industry” (4). Smiles's book extols the virtues of perseverance, industry, individualism, integrity, and probity. It also presents a series of biographies of historical figures who rose from obscurity to fame and wealth. Their inclusion is meant to encourage ordinary working people to improve themselves and, while doing so, improve their communities. Hugh Cunningham highlights that Smiles' book, Self-Help, has enjoyed unprecedented success, selling more than a quarter of a million copies, and was reprinted fifty-two times before his death in 1904. In addition to its outstanding success, the book has commonly been considered to have sketched out the basic blueprint for the self-help genre to serve as a tool for individual empowerment and social change. Smiles starts his book by defining his conception of self-help as follows:

The idea that good fortune is not a matter of divine intervention but rather the logical result of an individual's hard work and ingenuity is a point that Smiles reiterates throughout his work. "The voice that Samuel Smiles gave to this vision, in Self-Help," John Hunter argues, "touched a chord in millions of ordinary people, struggling to see, in a world of frightening change, a meaning for their own lives" (3). The early emphasis on hard physical labor and moral rectitude as necessary ingredients for gaining success had not lasted long. Towards the end of the nineteenth century, the self-help genre began to take a different direction, shifting away from the Puritan values and ideals that had been prevalent during the earlier centuries towards the liberal values and ideals that resonated through American popular culture in the late nineteenth century. Mercè Mur Effing attributes this shift in direction in part to "an ever-growing public looking for alternative belief systems to quench the thirst for inner peace and happiness in a materialistic-oriented society" (135). He goes on to argue, "The changing economic circumstances with a decline in wages, and an increased uncertainty about employment stability and opportunities, have created a context in which one of the only reliable insurances against economic insecurity seems to be self-improvement" (Effing 135). Such concepts as personal growth and wealth accumulation soon became two inseparable elements that shaped the discourse of self-help literature throughout most of the first half of the twentieth century. This is reflected, for instance, in Russell Conwell's 1915 Acres of Diamonds. The book preaches against the puritanical tradition – which bitterly criticized the pursuit of wealth and equated it with greed and dishonesty – claiming instead that the attainment of wealth is both a moral obligation and a religious duty: "To make money honestly is to preach the gospel" (Conwell 18). The text goes further to argue that wealth lies within the reach of any upright and hardworking individual: "I say you ought to be rich; you have no right to be poor" (Conwell 251). Napoleon Hill's Think and Grow Rich (1937) is another influential self-help book of the era. It puts forward a new philosophy of wealth creation that is said to be based on an analysis of more than 500 men who rose from modest origins to great prominence and wealth. He believed, "If you truly desire money so keenly that your desire is an obsession, you will have no difficulty in convincing yourself that you will acquire it. The object is to want money, and to be so determined to have it that you convince yourself that you will have it". (Hill 25) Also central to the self-help discourse during the first half of the twentieth century was the subject of business success which reached its apex in the 1930s. An explicit example of this can be found in Dale Carnegie's How to Win Friends and Influence People (1936), which offered a set of tools and principles on how to be successful in business. The book begins by recounting a story of an employer who had mistreated his employees and had never appreciated their efforts. Only after reading the book and applying the techniques it contained, was he able to win their hearts and turn their hatred into reciprocal friendship. By the second half of the twentieth century, authors of self-help books shifted their attention to the so-called "mind power" or "mind control" arena. These authors assert that life events are unequivocally the result of the workings of conscious and subconscious minds and that in order for people to be able to change their lives, they must first change their thoughts. Norman Peale was an early proponent of this view, and his 1952 book The Power of Positive Thinking was one of the very first works to take up the theme of mind power. From the outset, the author lays out what he describes as "a simple yet scientific system of practical techniques for successful living that works” (xi). In such a system, success and happiness, which are the ultimate objectives of every human being, are not attainable through our hard work or merit, but simply by our thinking about them: "Hold that picture, develop it firmly in all details, believe in it, pray about it, work at it, and you can actualize it according to that mental image emphasized in your positive thinking" (Peale 223). Joseph Murphy was another prominent self-help author of this period. He holds similar beliefs about the latent powers of mind that all humans equally possess and can use to their advantage. This philosophy is made clear in The Power of Your Subconscious Mind (1963), in which he asserts that "your subconscious mind is the master mechanic, the all-wise one, who knows ways and means of healing any organ of your body, as well as your affairs" (75). He then prescribes that, in order to remove the obstacles and challenges that keep you from reaching the success you deserve, you need to "picture yourself without the ailment or problem. Imagine the emotional accompaniment of the freedom state you crave. Cut out all red tape from the process" (75). In 1977, Jose Silva published a similar text on his mind control method. Since the 1990s, the genre of self-help literature has expanded exponentially, with a wide array of titles covering many different aspects of an individual's life and welfare. Micki McGee reports that, in 1997, the Barnes & Noble Bookstore in Manhattan's Union Square dedicated “a quarter mile of shelf space" to accommodating the newly emerging varieties of self-help literature (11). Along with their expansion, self-help books have also enjoyed wide popular appeal both in the United States and around the world. An earlier account of this phenomenon is given by Janet A. Simons, Seth Kalichman, and John W. Santrock. They point out that the self-help publications of the late twentieth century have represented an essential source of information for millions who seek advice and guidance on how to enhance their personal capabilities and communicative skills, cope with psychological-related difficulties, or gain a greater understanding of their personal identities as well as their inner feelings (25). The 1990s also saw the inception of marriage-related self-help books. The overall goal of these books was and is to help married couples improve their marital relationships and work out their marital issues. The rise of the women's rights movement in the US during the latter years of the twentieth century is believed to be a key contributing factor leading to the emergence of this sub-genre of self-help works on marriage relationships. The movement sought, among other things, equal rights and mutual responsibilities in marriage. Despite being a recent introduction to the genre, self-help books on marriage relationships have rapidly become one of the fastest-growing publishing industries in the US and perhaps across the world. John Gray's Men Are from Mars, Women Are from Venus is a testament to the wide popular appeal of this topic. It has sold more than fifty million copies worldwide and has been translated into at least forty-two languages since its publication in 1992, according to Barbara McMahon. The expansion occurring around this period has by no means been limited to the topical sphere. Over the past two decades, an increasing number of counseling practitioners and mental health professionals have begun to incorporate books of self-help into their practice as a potentially effective approach for treating common emotional and mental health disorders such as stress, anxiety, and depression. The following section offers an overall picture of the phenomenal success and wide-ranging influence of self-help books. It also demonstrates the special characteristics that have endeared them to the public.

Commercial Success of Modern-Day Self-Help Literature

Originating in America and then spreading across the world, the self-help book has become an unstoppable juggernaut in the last few years. According to a 2010 report released by the National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, the American self-help industry has witnessed a pivotal change for the future of its market with as many as 2000 self-help books of different sorts being published annually. Furthermore, McGee – in commenting on the large-scale circulation of self-help works – remarks that "one-third to one-half of Americans have purchased a self-help book in their lifetimes" (11). In 2016, the worth of the entire American self-help market was found to constitute an estimated $9.9 billion USD, and this figure was expected to exceed $13.2 billion USD by 2023 (Larosa). Several attempts have been made to answer the question regarding the factors that have contributed to the extraordinary success of present-day self-help literature. Dawn Wilson and Thomas Cash, having examined the specific aspects that are associated with positive attitudes towards self-help materials, conclude that the current growing demand for quick and easy-to-understand information and sound advice on how to cope with practical problems of everyday life is causing many people who expect instantly accessible resources when making purchase decisions to turn towards the self-help market (120). Others, like Jennifer Mains and Forrest Scogin, attribute the remarkable growth of the self-help sector to a number of empirically observed factors as follows: affordability, privacy, excitement, and accessibility (237-246). In addition, Micki McGee, in her account of the elements responsible for the boom in this body of popular nonfiction literature, emphasizes that the destabilizing tendencies in today's labor market have created an overall sense of insecurity among American workers, pushing them to seek out solutions to self-manage their own problems (13). Alternatively, Suvi Salmenniemi believes that the lack of sufficient and affordable health services along with a distrust of the official psychological care system are encouraging more and more people to resort to self-help literature for advice in areas such as health and well-being, interpersonal relationships, and careers, thus resulting in the constant demand for self-help books (68).

Self-Help Books: Definition

Self-help books have been defined in a variety of ways. Before delving into these various definition , however, it is important to note that there is a general consensus among both researchers and readers of this body of literature that these books are invariably designed to serve an educational function. In 2012, for instance, a team of researchers from the University of Calgary conducted a study to investigate the goals that readers associate with reading self-help books. The team found that 93% of them had set explicit learning objectives for themselves such as how to let go of ill feelings, how to change negative thought patterns, how to lose weight, or how to maintain a healthy lifestyle. Beyond this point of consensus, it is fair to say that there is little agreement as to what these books actually are. Hazar Alkheder describes this issue by saying that "there is some scholarship on the nature and function of [self-help] books, although even the precise definition of [self-help books] is not yet a settled matter" (438). As has already been mentioned, a key objective of this article is to compose an operational definition of self-help books that can be uniformly applied to disambiguate them from other related forms. To realize this objective, we need to review a range of existing definitions for the term. One early definition is provided by Starker who describes them as explicit instruction manuals for increasing health, wealth, and happiness. He further illustrates that these books are usually written in a "simplified manner appropriate to a wide readership, making few demands upon prior knowledge or scholarship" (2). Another definition is provided by Brad Johnson and William Johnson who define them as" any book, other than the Bible itself, which has been written to help you improve, change or somehow understand your personal qualities, relationships, mental health or faith" (183). They go on to assert that the focus of these texts is to "provide encouragement, information, or advice to readers who wish to help themselves" (183). Neither definition is broad enough, as they both confine self-help books to those concerned with developing and enhancing aspects of an individual's life, thus excluding a substantial number of self-help books dedicated to addressing emotional and psychological problems, including marital distress, depression, anxiety, stress, relationship breakdown, and addiction. McGee defines them as easily accessible and readily available advice books that virtually "cover any and all issues, with titles specialized to address every market segment" (12). She further explains that millions of people turn to self-help books "to boost their spirits and keep them afloat in uncharted economic and social waters" (12). This definition widens the scope of self-help so much that it includes many different types of advice books, manuals, and guides (e.g., cookbooks, conduct books, housekeeping books, and even sewing books) that are not necessarily perceived as self-help books. As such, unlike the previous definitions, which were too restrictive, this one is too all-encompassing. Sandra Dolby constructs a more precise, but still unsatisfactory, definition of self-help books in her effort to set them apart from other genres of popular literature. For her, these types of texts are defined as "books of popular nonfiction written with the aim of enlightening readers about some of the negative effects of our culture and worldview and suggesting new attitudes and practices that might lead them to more satisfying and more effective lives" (Dolby 38). Even this definition has its shortcomings too, for, on the one hand, it looks at books of self-help within the narrow context of fixing cultural ills – as opposed to individual and relational ills; on the other hand, it appears not to differentiate self-help texts from other types of religious writings such as sermons. A further inadequacy of Dolby's definition is that it is self-contradictory for the reason that she identifies self-help books as nonfiction books, and then later mentions James Redfield's The Celestine Prophecy (1994), which is generally classified (e.g., in bookstores and libraries) as a fictional novel or a self-help book written in a parable form (see Dolby 41). As shown earlier, self-help books take on a therapeutic meaning within the counseling profession where they serve as an adjunctive form of therapy offering information and techniques derived from psychology to address emotional and psychological disorders. It is therefore imperative, in the absence of an agreed-upon definition, to elucidate what exactly is meant by self-help books. These books should be defined as inspirational texts that are crafted for instructing the general public on issues pertaining to their personal, professional, as well as domestic lives, and for providing support in overcoming these issues. Such books are commonly characterized by the use of simple grammatical structures and lexicon, an engaging tone, and an interest-catching title. They also feature a variety of literary devices such as personal narratives, parables, rhetorical questions, lexical repetition, and figures of speech, which are primarily intended to enhance the persuasive appeal of the arguments contained in them. The following section presents a further illustration of these books, highlighting their topical breadth and proposing a new model for classifying them.

Self-Help Books: Themes and Classification

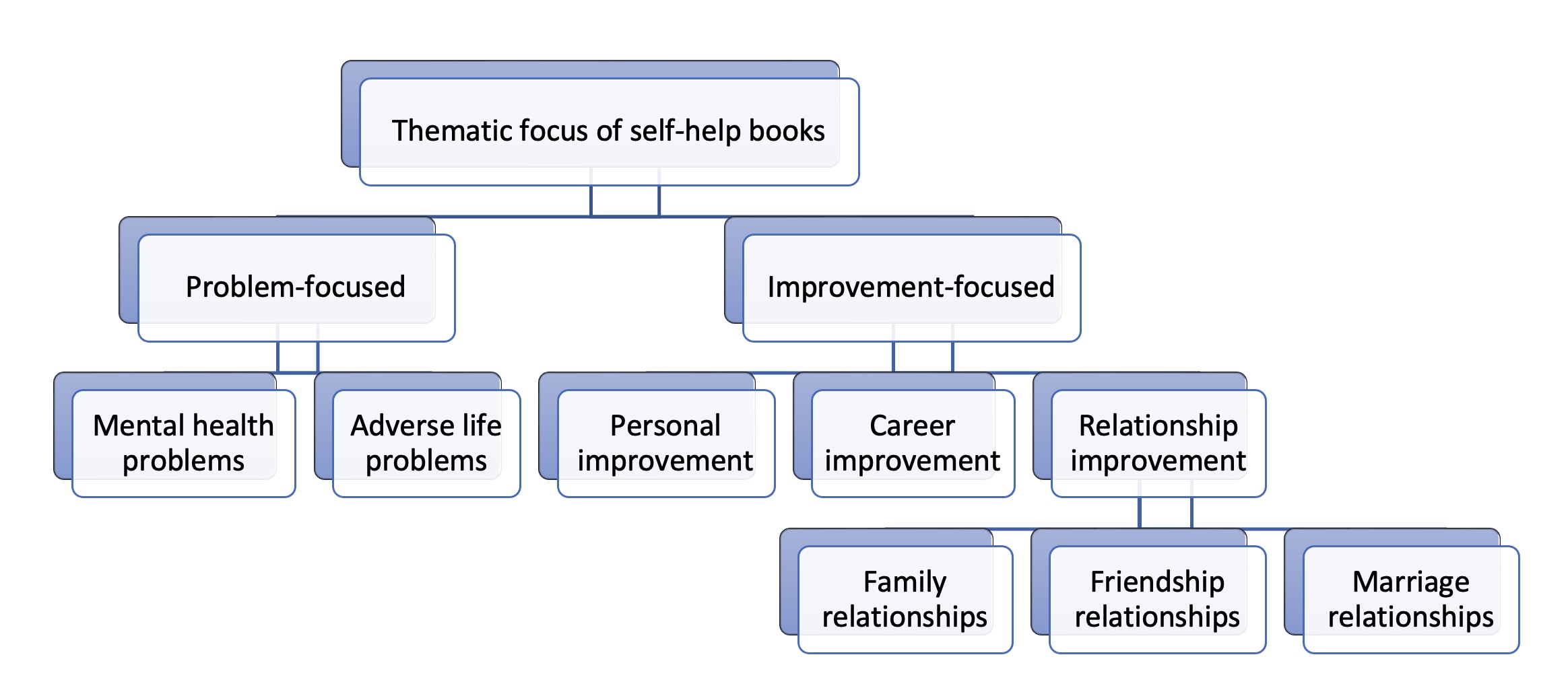

This classification model focuses on the therapeutic uses of self-help books within psychotherapy. It thus overlooks the bulk of other self-help books that aim at enhancing personal and relational capabilities. In contrast to Pantalon’s clinically-focused categorization, Ad Bergsma draws up a wide-ranging classification wherein self-help books are grouped under four large headings according to the main subject matter. Such a classification is said to be produced following an analysis of forty-eight best-selling self-help books published during the period of September 1999 until August 2000. The first group is entitled Growth and covers books that center on the subject of self-cultivation and improvement (Bergsma 344). The second group is Relationships and is comprised of books that focus on enhancing communication skills (344). The third group is Coping and contains books that offer practical tips on how to deal with stress in working life (344). Also belonging to this group are books that deal with improving resilience in stressful circumstances (344). The last is Identity and includes books that help develop one’s sense of identity (344). Such books, as Bergsma points out, are similar but less practical than the books on growth first mentioned. A fourth classification is set forth by Dolby who identifies three broad types of self-help books based on the linguistic form in which they are written: the parable, the essay, and the manual (or how-to book) (40). She describes the parable as a distinct form of writing that is often employed by modern self-help authors to convey one or more instructive lessons or principles for their own readers to learn (Dolby 42). The following are all examples of self-help books that are written in the parable form: Gifts from Eykis, The Celestine Prophecy, The Alchemist, and Way of the Peaceful Warrior. Dolby then discusses the essay form, which she considers to be the most commonly used form of self-help books (42). This form offers the unique benefit of treating a subject in an exhaustive manner, for it is "open-ended and friendly to the practice of recirculation, expansion, revision, or even simply restating in a new way" (Dolby 42). A further distinction is made by Dolby in order to differentiate between three sub-types of self-help books that use the essay form: (a) the workbook (e.g., The Artist's Way), (b) the story collection (e.g., Chicken Soup for the Soul), and (c) the textual interpretation (e.g., Living Happily Ever After) (42-43). Self-help authors also use the manual form for the expression of their ideational contents, but such use is not as extensive as the other two and is often restricted to the domains of business and time management (40). Dolby argues that the objective of writing in the manual form is "to guide readers through a set of learning strategies that can be applied in a variety of contexts" (41). The following are examples of the manual form of self-help books: How to Get Control of Your Time and Your Life, Confidence Course: Seven Steps to Self-Fulfillment, and Rules and Tools for Leaders. Problematically, no single classification of self-help books can be applied to all research studies within the field, nor has there been one that could comprehensively capture all relevant themes featured in the field. In fact, all such classification models were informed by a particular understanding of the meaning and scope of self-help books at a certain time. Thus, these models of classification need to be modified. The purpose of what follows is, therefore, to extend the existing schemes of classification for self-help literature to allow for a spectrum of other themes and topics to be covered. In the proposed classification here, self-help books are assigned to separate categories on the basis of their thematic focus. As stated earlier, an improved, thematic-based classification scheme is needed to organize this body of literature for researchers, which can be accomplished by succinctly grouping self-help books that share common themes or topics together. According to this schematic classification, a distinction is drawn between two major, distinct classes of self-help books as shown in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1

The first class is termed Problem-focused and consists of self-help books that are concerned with addressing specific problems that their readers are experiencing, followed by possibilities for their resolutions. This class of self-help books can be further divided into two categories. The first category focuses on offering prescriptive advice and measures for their readers to help them overcome mental health-related issues such as stress, depression, or anxiety. Some of the more well-known examples of these books are Don't Panic, The Stress Solution, and Feeling Great. The focus of the second category is oriented towards offering counsel and guidance to help their readers adapt to and cope with major life events and transitions including death of a loved one, separation, job loss, and retirement. Examples of books that fall within this category are Recovering from the Losses of Life, Transitions: Making Sense of Life's Changes, and You Can Heal Your Heart. The first sub-category encompasses self-help books that deal specifically with family relationships and parenting issues. Such books are intended for those with an interest to learn how to improve and reform relationships and interactions within the familial context. The following are some examples of these books: The 7 Habits of Highly Effective Families: Building a Beautiful Family Culture in a Turbulent World; The World's Easiest Guide to Family Relationships; and The Blessing: Giving the Gift of Unconditional Love and Acceptance. The second sub-category consists of self-help books that are aimed at the development and improvement of friendship relationships. They offer practical instructions to help their readers enhance their socialization skills, make and maintain real friendships, or even increase their popularity. Some examples of these books are as follows: Friendshifts: The Power of Friendship and How It Shapes Our Lives; Stop Being Lonely: Three Simple Steps to Developing Close Friendships and Deep Relationships; and Frientimacy: How to Deepen Friendships for Lifelong Health and Happiness. The final sub-category comprises self-help books that are designed to provide married couples with knowledge, skills, and tools that they can employ to strengthen their marital relationships and improve the way they relate to each other. Here are some examples of such books: Don't Sweat the Small Stuff in Love; Relationship Rescue: A Seven-Step Strategy for Reconnecting with Your Partner; and Chicken Soup for the Woman's Soul.

Conclusion This article offers a revealing glimpse into the genre of self-help books, exploring its historical origins as well as its subsequent development into one of the world's most widely read genres. It also highlights the different factors underlying the phenomenal success and rapid rise of the self-help publishing industry at the turn of the twenty-first century. As a further contribution, this article provides a precise definition of self-help books, which, unlike previous ones, allows for a better understanding of what these books are about, why they are published, and how they are different from other seemingly similar forms of discourse. An expected consequence of this definition is that it settles the disagreement over the meaning and nature of the self-help genre. The final contribution is the creation of a classification system for self-help books that is based on thematic content. Compared to previously proposed classifications, this one is comprehensive, covering all of the topics pertaining to this genre. It thus has the potential to be employed in scholarly studies investigating the thematic areas of self-help literature.

Works Cited Alkheder, Hazar. "Translation of Self-Help Literature into Arabic." Routledge Handbook of Arabic Translation, edited by Sameh Hanna, Hanem Elfarahaty, and Abdel Wahab Khalifa, Routledge, 2019, pp. 437-446. Bergsma, Ad. "Do Self-Help Books Help?" Journal of Happiness Studies, vol. 9, no. 3, 2007, pp. 341-360, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-006-9041-2 Blum, Beth. Self-Help Compulsion: Searching for Advice in Modern Literature. Columbia UP, 2020. Carnegie, Dale. How to Win Friends and Influence People. Simon & Schuster, 1963. Coelho, Paulo. The Alchemist. HarperTorch, 1993. Cronon, William. "The Trouble with Wilderness; or, Getting Back to the Wrong Nature." Uncommon Ground: Rethinking the Human Place in Nature, edited by William Cronon, W.W. Norton & Co., 1995, pp. 69-90. Conwell, Russell. Acres of Diamonds: His Life and Achievements. Harper & Row, 1915. Cunningham, Hugh. Time, Work and Leisure: Life Changes in England since 1700. Manchester UP, 2016. Dolby, Sandra. Self-Help Books: Why Americans Keep Reading Them. U of Illinois P, 2008. Douglas, Anne Helen. The Society of Self: An Analysis of Contemporary Popular Inspirational Self-Help Literature in a Socio-Historical Perspective. 1979. McMaster University, Master's thesis. Effing, Mercè Mur. "The Origin and Development of Self-Help Literature in the United States: The Concept of Success and Happiness." Atlantis, vol. 31, no. 2, 2009, pp. 125-141. ---. US Self-Help Literature and the Call of the East: The Acculturation of Eastern Ideas and Practices with Special Attention to the Period from the 1980s Onwards. 2011. University of Barcelona, PhD dissertation. Gray, John. Men Are from Mars, Women Are from Venus: A Practical Guide for Improving Communication and Getting What You Want in Your Relationships. HarperCollins, 1992. Hill, Napoleon. Think and Grow Rich. Aventine Press, 1973. Hunter, John. The Spirit of Self-Help: A Life of Samuel Smiles. Shepheard-Walwyn, 2017. Ince, Robin. "The Ancient Roots of Self-Help." BBC Culture, 24 February 2022, www.bbc.com/culture/article/20140805-the-ancient-roots-of-self-help Simons, Janet A., Seth Kalichman, and John W. Santrock. Human Adjustment. Brown & Benchmark, 1994. Jefferson, Thomas. "Declaration of Independence: A Transcription." National Archives and Records Administration, www.archives.gov/founding-docs/declaration-transcript Johnson, Brad, and William Johnson. The Minister's Guide to Psychological Disorders and Treatments. Routledge, 2000. Larosa, John. "The $10 Billion Self-Improvement Market Adjusts to a New Generation." Market Research, 12 August 2022, blog.marketresearch.com/the-10-billion-self-improvement-market-adjusts-to-new-generation Madsen, Jacob. Optimizing the Self: Social Representations of Self-Help. Routledge, 2015. Mains, Jennifer, and Forrest Scogin. "The Effectiveness of Self-Administered Treatments: A Practice-Friendly Review of the Research." Journal of Clinical Psychology, vol. 59, no. 2, 2003, pp. 237-246. McGee, Micki. Self-Help, Inc.: Makeover Culture in American Life. Oxford UP, 2005. McMahon, Barbara. "John Gray: Forget Mars and Venus, The Problem Today Is When Husbands and Wives Are Too Alike." Daily Mail, 31 December 2021, www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-10359823/JOHN-GRAY-Forget-Mars-Venus-problem- Moody, Harry. Abundance of Life: Human Development Policies for an Aging Society. Columbia UP, 1988. Murphy, Joseph. The Power of Your Subconscious Mind. Gildan Media, 1963. Pantalon, Michael. "Use of Self-help Books in the Practice of Clinical Psychology." Comprehensive Clinical Psychology, edited by Alan S. Bellack and Hersen, Elsevier, Peale, Norman. The Power of Positive Thinking. Prentice Hall, 1952. Redfield, James. The Celestine Prophecy. Bantam Press, 1994. Salmenniemi, Suvi. Rethinking Class in Russia. Ashgate, 2013. Silva, Jose with Philip Miele. The Silva Mind Control Method. Simon & Schuster, 1977. Simpson, John, and Edmund Weiner. The Oxford English Dictionary. Clarendon Press, 1989. Smiles, Samuel. Self-Help: With Illustrations of Character and Conduct. John Murray, 1859. Starker, Steven. Oracle at the Supermarket: The American Preoccupation with Self-Help Books. Transaction Publishers, 1989. Wilson, Dawn, and Thomas Cash. "Who Reads Self-Help Books?" Personality and Individual Differences, vol. 29, no. 1, 2000, pp. 119-129.

|

Journal Home

AmericanPopularCulture.com