Judge and Life Excavate the Tomb:

Tutmania in 1922-1923

Americana: The Journal of American Popular Culture

(1900-present), Spring 2023, Volume 22, Issue 1

https://americanpopularculture.com/journal/articles/spring_2023/marks.htm

Valdosta State University

|

As newspapers, science magazines, and special calendars remind us, 2022 was the year to celebrate a history-changing event: the 100th anniversary of the discovery of King Tutankhamun's tomb by the Egyptologist Howard Carter. The location and contents of the tomb, untouched for more than 3248 years, provided invaluable information about a host of topics, including history, genetics, and cultural practices. It proved to be the kingpin in another respect as well: "Egyptomania," or "Tutmania" as it was sometimes called, erupted worldwide after the discovery. Lifestyles were affected in multiple ways, ways that are of interest even today ("King Tut Deco Egyptomania"). Fashion stylists incorporated Egyptian design and color; jewelers adapted ancient designs; the "Egyptian Bob" became a popular hairstyle; home décor changed; Egyptian costumes and references became common in dramatic performances and songs, such as the one pictured below (see Figure 1); and travel to Egypt increased exponentially. Even quotidian vocabulary was affected. The enthusiastic American response to the discovery of the tomb mirrored the response in other countries, and while many of these cultural reactions have been well documented, an important aspect of Egyptomania is often overlooked. That aspect is the way in which the discovery and public acclaim were depicted in American comic periodicals of the day. To examine the editorial and artistic methods that the two popular publications Life and Judge used to incorporate visual and verbal cultural commentary, then, is both a celebration of the discovery as well as an examination of how a foreign event impacted prosaic life, language, and thinking.1

Figure 1

Not only was the discovery of the tomb a matter of luck, but the dates cited for it may vary depending on the accuracy of the popular reports and the timing of the progress made. Howard Carter, who spent years working in the Valley of the Kings with the backing of Lord Carnarvon, began excavations at that site in 1915. By 1922, due to the lack of success, both were considering ending the search. Then, on the fateful day of 4 November 1922, one of the domestic workers – a water boy – told Carter that he had uncovered a carved step, and Carter, examining the site on the next day, found it to be part of a buried stairwell leading to a sealed doorway, which he believed was the entryway to the tomb. After Lord Carnarvon arrived on 23 November 1922, they descended, only to find that the door was heavily damaged, probably by grave robbers, and that it led to nothing but an antechamber full of rubble. Despite this impediment, they pressed on and came to another doorway sealed with Tutankhamun's name. The rest is history. Carter, who on 26 November 1922 peered through a small hole with the light of a candle, was awestruck: the tomb was filled with thousands of objects untouched since the day they were buried with the Pharoah for his eternal journey. The official opening of the burial chamber took place on 17 February 1923 ("Discovery Timeline"). As National Geographic writer Tom Mueller phrased it, "It was an archeologist's dream – and nightmare" (62). The long-awaited discovery answered and raised a host of questions. Both the stretch of time for the excavations leading to the discovery as well as the lengthy process of dismantling the tomb influenced the way in which satirical magazines of the day incorporated references to Egypt. From the beginning of Carter's excavations, news of Egypt, as well as travel to the country, became popular. By 1922, the year of the discovery, images and comments in popular magazines became more common with Life often citing comical drawings and clippings from periodicals abroad and Judge publishing original columns, jokes, and drawings that focused not only on the effect the excavations had on language but also on the way in which ancient habits influenced early twentieth-century American ones. Due to the fact that the discovery caused a revolution in American popular culture, the question remains: why were we then and still now so obsessed with ancient Egypt? The Egyptologist Kent Weeks suggests that the obsession comes from films and televised specials that encourage people to "insert" elements of the ancient into the modern (qtd. in Sivac). Nicky Nielsen, who examines that question in his book Egyptomaniacs, proposes a more complex reason. As he explains, although the answer often focuses on the beauty and the vastness of Egyptian cultural remains, there is a more subtle frame of reference: Egyptomania is, in effect, the result of the popularization of a culture that "is both comfortably familiar and excitingly alien," a culture balanced between known history and belief in mystical events, such as the "pharaoh's curse" that purportedly caused Lord Carnarvon's death (Nielsen 104). There is, in addition, another underlying reason for the popularity of the discovery: its timing helped contribute to the widespread social effect. As Lizzie Glithero-West sagaciously points out, "a society in mourning, plagued with uncertainty and recovering from the First World War, looked hopefully into the face of Tutankhamun and saw themselves, and in so doing perceived a means of recovery" (127). Harold Carter's first view of the tomb revealed not just an unprecedented "treasure-trove of the ancient decorative arts," a priceless collection of untouched artifacts, but also a "time-capsule" of "something uncannily reminiscent" of what the public had suffered: the loss of so many of its sons and husbands in the war (Glithero-West 127). The iconization of King Tut suggested a more inclusive resurrection of those who were lost. Her assessment is that, visually speaking, it also provided its "greatest impact...on fashion and jewelry," partly because those elements existed as personal reminders of family and friends who had died in the war (Glithero-West 127). But more to the point of this article, Egyptian iconization also impacted the American publishing industry with satirical magazines like Life and Judge adopting the discovery as a theme in multiple ways. Life, founded in 1883 by John Ames Mitchell and Andrew Miller, became well known for its illustrations and commentary by such artists as Charles Dana Gibson and Norman Rockwell and such writers as James Metcalfe, Robert Ripley, and Dorothy Parker. Launched two years earlier by William Arkell, Judge, which had convinced cartoonists like Bernard Gillam to leave the successful magazine Puck, focused more on satire. Soon after, Judge became renowned for its cartoons, both political and cultural, as well as for its support for William McKinley and the Republican party, in direct opposition to Grover Cleveland (Mott, vol. 3, 552-556 and vol. 4, 566-568; Marschall 141-152; Grant 111-120). Both magazines became popular for their satirical illustrations and pointed commentary, which invited the reader through laughter and reflection to obtain an understanding of both local and foreign events. Examining how these popular satirical publications reacted to the discoveries in Egypt provides a perspective on the way in which the archeological findings metamorphized into what was called "Egyptomania" and "Tutmania" in American popular culture and beyond. For Judge, the quips and comments that were related to the discovery of King Tut's tomb were preceded by references to earlier Egyptian excavations, thereby heralding the later discovery by acclimating its readers aurally to the sound of Egyptian names and visually to Egyptian fashions. The resulting effect was a parodic congruence between the two countries' lifestyles. Given the outpouring of comments, advertisements, and cartoons evoked by the opening of the tomb, Judge's note on 24 March 1923 was both typical as well as accurate: "It will be a poor fish of an Egyptian cigarette maker who doesn't advertise his brand as Tutankhamen's favorite smoke" (Hill 26). Indeed, the dispute about Egyptian pronunciation is often pinpointed by Judge, which on 7 April 1922 offered "Tut-ankh-amen, Tut-ank-hamen, Tu-tanka-men, Tuta-ankham-en, [and] T-uta-nkh-ame-n" as possibilities (Hill 22). The problem of translation that also existed was explained comically when a museum assistant became "perplexed" about poorly transcribed content on a papyrus and was told by the curator, "Just call it a doctor's prescription in the time of Pharaoh" ("Pharoah's Pharmacist" 6). Similarly, the discovery of a headless Egyptian princess is explained as the result of a commonplace solution to a domestic dispute – beheading – which would occur if the princess had asked her husband, "Where have you been?" ("Cutting Off" 26).2 Short quips and references like these illustrate the way in which Judge domesticated foreign references. Perhaps more pertinent in terms of incorporating Egyptian references with its readership's interests, Judge published a number of suggestive theater illustrations. On 25 February 1922, for instance, the magazine released a full-page photomontage of four dancers included Kyra, a performer well known for her "contortionistic and muscular dancing" as well as for her portraiture by a number of artists, the most famous being "Lifedrift," a statue displayed at the Museum of Art in Boston ("Kyra" 4). Dressed in a scanty outfit, with head covering and long train, she was described as "an Egyptian Deity" performing at the Winter Garden on Broadway ("This Is Kyra" 15). A full-page illustration on 1 April 1922 entitled "Arthur Little Takes a Trip 'Up in the Clouds'" references both the artist and the musical performed at the Lyric Theatre in New York from 2 January 1922 to 18 March 1922. The spread depicts various actors, including Mark Smith and Dorothy Smoller in a warm embrace, with the illustrator commenting that the character Freddie, falling for "the Egyptian deity," empties his bank account "to cover the poor girl with jewels. She has no other clothes!" ("Arthur Little" 14). Another early example in Judge is "Mummies That Move," a detailed, five-star review of The Loves of Pharoah, a German film directed by Ernst Lubitsch. The column, appearing on 8 April 1922, provides an early and more thoughtful assessment of the influence Egypt had on modern creativity. Written by Heywood Broun, a well-known journalist and founder of the American Newspaper Guild, and illustrated by Bertram Hartman, whose art was exhibited in prominent museums across the country in addition to his work as an illustrator for Judge, the spread banked a solid, well-written review with a somewhat waggish drawing of the actors as Egyptian characters (see Figure 2; "Heywood Broun"; Elton 177; "Mummies" 14). That these theatrical references to Egypt in drawings, photographs, and written commentary not only attracted influential contributors but also were deemed important enough to be offered to Judge's readership speaks of the magazine's awareness that its readers were cognizant of the ongoing excavations in Egypt and welcoming Egyptian motifs into everyday life.

Figure 2

That cultural welcome was illustrated in Judge in other, less obvious ways by verbiage inserted into quips and captions. A typical example is a joke about a wife who complains that although the news is rife with commentary on King Tut, she lacks Egyptian clothing; her husband counters with the suggestion that she "try being as silent as the Sphinx" ("Modernity" 31). Another reference to what was considered fashionable is found in the caption "So rapid is the fad for things Egyptian that the wives of some of our million-dollar-a-year men may insist upon a couple of genuine Rosetta stones set in earrings" ("So Rapid" 26). Like Judge, Life included puns and wordplay related to the discovery, such as "Tut-ankh-Amen isn't to be unwrapped for another year. There's too darn much red tape about a mummy" ("Tut-ankh-Amen" in "Life Lines" 12). The magazine also adopted a similar approach to Judge's linkage of Egyptian references to early twentieth-century diction and habits. During the preliminary excavations in 1922, Life's use of related words like "Egypt" and "Tut" became more common, especially when pertaining to fashion: for instance, a comment linking women's modern hair and clothing styles to those of their ancient counterparts announced, "An Egyptian mummy with bobbed hair has been found. They are digging for the goloshes now" ("An Egyptian Mummy" 10). The next year, Life verified the continuing development of "Egyptomania" with the publication of a poem by A.G., which ended with the lines:

Last week was it Turkish, Hungarian,

The poet's prediction about the sweeping cultural changes that will take place are considerable: he complains about our "conniptions" over the Egyptians; mentions increased travel, which will cause what he calls "a deluge of gammon"; and expresses concern about the "dangerous dances" as well as dramas of "blood and horrifics" (A.G. 13). The poem concludes with a criticism of the American propensity to discard native culture in favor of others. In addition to short allusions, both magazines provided their readers with a wider perspective by republishing and translating foreign comments and cartoons. Life, for instance, included reprinted drawings in several of its columns. "Aut Scissors, Aut Nullis" features one that originally appeared in the German Lustige Blätter: Mrs. Tut-ankh-Amen, sitting up in her tomb and addressing her discoverers, wails "Heavens, how humiliating! My hat is so dreadfully out of style!" ("Mrs. Tut-ankh-Amen" 28). Another column, "Our Foolish Contemporaries," includes the poem "Antiquity" by E. Merrill Root from the abolitionist newspaper The Liberator:

An old Egyptian hieroglyph

Other comments in Life that connected ancient Egypt and modern-day culture also questioned the Tutmaniac focus on the connection between ancient Egypt and early twentieth-century America. Quoting "a cynic" from the Glasgow Bulletin, Life's "Aut Scissors, Aut Nullis" compares "B.C. 1100 – Funeral rites" with "A.D. – Cinema rights" ("Tut-ankh-Amen" 30). These often short but pertinent borrowings, coupled with the magazine's own quips and puns, suggest not only the direction that the discovery will take in affecting common popular concerns but also the criticism that such a focus on all things Egyptian evoked. Not unexpectedly, with the official opening of the burial chamber on 17 February 1923, popular publications were inundated with photos, descriptions, and interviews. While both Judge and Life stayed current by melding Egyptian references into comments, quips, puns, and cartoons, Judge was the most focused on the discovery, perhaps because its business connections had changed five years earlier, when John A. Schneider, former editor of Leslie's Weekly, became the owner of the Judge Company. The new connection broadened the political focus and, as Frank Luther Mott stated, not only made the contents "brighter" but changed the magazine from being primarily comic to "departmentalized" – in other words, focus was placed on special subjects, such as book reviews, movies, sports, automobiles, etc. (554-555). The March issue of Judge contained Egyption commentary from an advertisement for the "King Tut Good Luck Ring" to comments on fashion (20). Much of Judge's attention was devoted to the international effects of focusing on Egypt, suggesting, for instance, that a British child "will grow up to call his mother 'Mummy'" ("Princess Mary's Baby" 3). Questions and jokes about pronunciation abounded, "Toot-uncommon" appearing, for instance, in Walter Prichard Eaton's semi-serious book review of The Life and Times of Tut-ankh-amen by the Egyptian Bioshara Nahas. Eaton's humor is less significant than his attempt to rectify the ongoing mispronunciation of the King's name by recommending "a most interesting" book by an Egyptian author (31). Other fictitious accounts of King Tutankhamun's life focused on relating him to the recognizable activities of the readership. One example that weaves both together is the poem by George H. Hubbard, "A Lay of Ancient Egypt":

A sporty king was Two-tank-amen,

Here, Hubbard relates a mispronunciation and misspelling to King Tut's tendency to drink "tankards...of every liquor," making fun of modern-day habit and the "sages" (like Eaton and Nahas) who prefer an accurate pronunciation. Similarly, "You Tell 'em, Tut," a short piece in Judge's editorial column debating the value of being buried with treasures "to be disturbed later by an inquisitive and excitable generation" or of choosing "a simple grave and privacy" closes with two pertinent questions of the day: "How does it feel to be setting the styles for 1923?" and "How the help [sic] do you pronounce your name?" (13). Not all commentators accepted the humorous side, however. A more serious response on 31 March 1923, well in line with Judge's ongoing cultural focus, references the distress of William A. Hammond, dean at Cornell University, who criticized the excavation as a desecration, calling it an "utter irreverence" and asking how we would feel about the excavation of Washington's or Lincoln's bones 3,000 years from now ("Prof. Hammond" 3). In a related column later that year, the editorial "Egyptian Papers Please Copy" reports the English refusal to allow the Oglethorpe University president to exhume the remains of General Oglethorpe, who founded the colony of Georgia in 1732. As the editor comments, "we do hope that the spirit of Tut-ankh-Amen, pursuing with his fatal curse the desecrators of his tomb, will pause long enough to comprehend the full significance of this episode in the country of Lord Carnarvon" (who died on 5 April 1923) (19). Perhaps the single poem in Judge in early 1923 that best encapsulates the various effects of the tomb's discovery was written by the Chicago journalist Keith Preston, a well-known scholar, academic, and humorous poet ("Keith Preston Papers"). Given a life-long interest in literature and language, he effectively and humorously covers the gamut of possible Egyptian cultural influences in his poem "The Latest Crime Wave," which begins with a reference to Paul Poiret, a popular fashion designer of the twenties:

Poiret will get his model

While the poem is subtly satirical, it accurately predicts how the discovery of the tomb will affect what happens in quotidian affairs. Fashions will change as will décor and mannerisms; writing will be affected; and names both of pets and people will likely be altered to fit the new Egyptian perspective. As the year 1923 progressed, the comments in Judge became more detailed and connected to actual events and well-known figures, sometimes reversing the trending "Egyptification" by applying American comments to Egyptian life. "What We May Expect from the Egyptian Tomb," for instance, was contributed by Carl Shoup, a Stanford student who later became an economics professor well known for reforming the tax code for Japan ("Carl S. Shoup"). "What we may expect" included "[c]ards from the midnight lunch-counters along the Nile," "[c]hariot bills – five cows per hour," "[l]atest copies of La Vie Egyptienne," "Sandy Stories," and "The Lover's Handbook (sent in plain wrapper)" (Shoup 6). Passing references to the impact of the Egyptian influence on sports included a prediction relating the growing fad of dancing to football games. One suggestion was that if Harvard hired Ruth St. Denis, an influential modern dance pioneer, the "King Tut shift and the Pharoah formation will...become part of the equipment of future Cambridge elevens" ("Gridiron Aesthetics" 38). Card games were also included: the cartoon "Faro and Bridge," for instance, shows a procession of Egyptians in carts decorated as playing cards, with the ace labeled "Cheops" ("Faro" 19). Captioned "If Egypt had known Hoyle," the drawing weaves together a reference to Edmond Hoyle, a well-known eighteenth-century compiler of card game tactics and rules, with ancient Egypt and modern card-playing (see Figure 3; "Faro" 19).

Figure 3

In contrast to Judge's somewhat more historically-oriented view, Life magazine inundated its readers with a host of cartoons, quips, and verses, not only predicting Egyptomania but amplifying it. In the 19 April 1923 "Egyptomania" poem, A.G. explains:

At present we're throwing conniptions

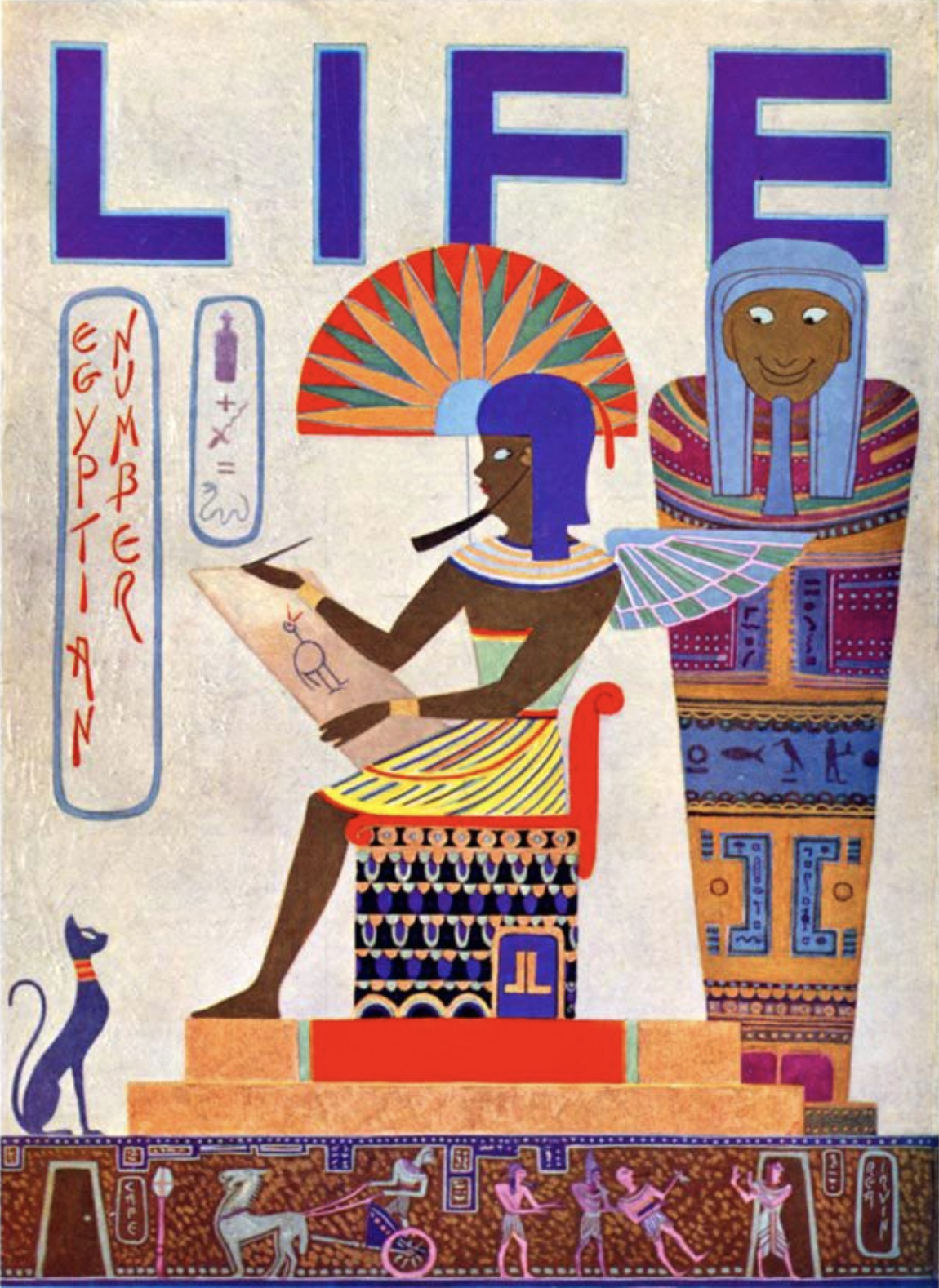

Describing travelers, teachers, and playwrights as well as "sinuous-angular minxes" who are "[a]ttired as sphinxes," A.G. accurately depicts the trends to come (13). After the opening of the tomb, the reaction of Life was mixed. One thoughtful editorial dealt with the effect of the tomb's discovery on developing a metaphysical perspective about life after death, with the writer noting the excessive treasures in the tomb. "Spiritual acquisitions," not material acquisitions, should be considered by those intent only on making money and gaining material possessions ("Meanwhile" 14-15). In addition, comments were plentiful in the recurring tongue-in-cheek column "Things LIFE Would Rather Like to Know," including evaluating the treasure's value "in terms of anthracite" and asking "[w]hat is Lord Carnarvon's honest opinion of lèse-majesté?" ("What Is the Actual Value" 8; "What Is Lord" 10). The 19 April 1923 issue of Life, however, best highlights the magazine's version of Egyptomania by sporting a cover that features the figure of a mummy salaciously eyeing an enthroned Egyptian woman with a sketchbook (see Figure 4). Not all the content was devoted to the discovery, however; the issue also featured a variety of other columns and cartoons. Egyptomania was introduced in the first content page, however, featuring the letters of "Life" redrawn as Egyptian symbols, a poem "The Princess at Luxor" by Katharine Parker Thore, and a cartoon of a well-dressed woman looking at a mummy and commenting, "Gracious, how homely the women were in those days!" (4). That cartoon was augmented by another later in the issue, showing a young girl commenting to her mother, "I don't see why there were so many mummies and no daddies" (13). No further references appeared until five pages later when the word "Scarabesques" headlined four short cultural comments.

Figure 4

Life's focus was essentially twofold: first, on the way the discovery impacted its readers' lives and habits; and second, on the way in which American phraseology and perspectives connected with the Egyptian artifacts. In both cases, the two cultures were, in effect, being woven together even if much of that "weaving" was humorous. For instance, "The Broadening Influence of Travel," a centerfold cartoon in the 19 April issue, consolidates the home-focused comments of a wealthy man touring the sights and sounds of foreign countries. Even more detailed is the full-page illustration "Fragment Depicting Incidents During the Reign of Nor-mal-cy I," which transforms Egyptian imagery and dress into a golfing tournament (see Figure 5; "Fragment" 15).

Figure 5

Life's continuing discussion about Tutankhamun can permeate even private moments as suggested by the newspaperman and advertising specialist Tracy Hammond Lewis ("Tracy Hammond Lewis"). His "Twin Bed-Time Stories: Benedict Learns of the Egyptians" pairs a wife who knows about the excavation with a disparaging husband who says that the Pharoah's name, "Sounds like the report of an automobile accident – toot-honk-amen!" (21). The same issue also included a full-page "newspaper" entitled "The Daily Papyrus," dated "41144 BC" and marked as "All the Hieroglyphics Fit to Cut," which featured a series of articles that rephrased the day's news in Egyptian terms. For instance, the pyramid builders at the Cheops Construction Company stage a walk-out; Judge Hammurabi is scheduled to arraign prisoners taken during the Theban Lotus Eaters’ Club; and the Cleopatra's Needle and Sewing Society held a picnic (20). Again touching on the pronunciation question, the "News in Brief" section announces the death of King Tut, who "choked to death trying to teach some visitors how to pronounce his name correctly" (20). Of all the columns in the 19 April issue, however, "An Egyptian Episode" refers most directly to the discovery. Written by Walter E. Traprock (pseudonym of the prolific writer George Shepard Chappell, architect and parodist), it features Traprock himself explaining to a curator at the Harvard Fogg Museum the insignificance of Howard Carter's discovery. Traprock, who claims to have earlier discovered the tomb of the first Pharoah Dimitrino (the trade name for a Greek tobacco factory in Cairo), is annoyed at being unrecognized for political reasons, among them an effort on England's part "to pay off the British debt [to America] in beads and buttons" (12, 31). Traprock also rails against Carter, who took down a door to "Tout-en-Carmen's" tomb instead of burrowing and using a "patent cigar lighter" in the darkness (12, 31). Once inside, Traprock claims to have seen drawings of the Pharoah "playing Mah Jongg, using the telephone" and statues of "the tutelar divinities, Psh, Shs, Pst, and Tk, the Big Four of their day" (12, 31). After Life's Egyptian issue, references in the magazine like these became less plentiful, although the interjection "tut-tut" appears multiple times, treated as a "Presidential Interjection" by William Jennings Bryan and spoken by the "Fashion Imp" in response to "masculine uncertainties" ("Everyday Behavior" 32; "Ballad" 12). To look at the reaction of the two major comic magazines of the day, then, is to see not just quips and puns, comic drawings and commentary, but a reflection of the larger, more serious cultural ramifications of the tomb's discovery. Archeologically, it was a phenomenal moment, helping to clarify an important era of Egyptian history and providing its excavators with a treasury of objects not seen for more than 3300 years. But it was also a discovery that affected the man and woman in the street. As knowledge of King Tutankhamun spread, Egyptian mottos and artistic interpretations became prevalent. In effect, Egypt was brought home to those who could or did not travel, through changing fashions, jewelry, and theatrical improvisations, and especially through the comic responses of magazines like Judge and Life. Language was also affected, with numerous versions of the Pharoah's name incorporated in comments and verse. The humorous reaction, a comic mirror to the scientific analyses, made the foreign familiar and brought the ancient up-to-date.

Notes 1. Copies of Life and Judge are available online at the HathiTrust Digital 2. While not the focus of this article, racism and sexism in some of the archival materials may be evident to twenty-first century readers. More research needs to be done in this area of Egyptmania and Tutmania studies. Future scholars should consider writing and publishing on this fertile topic.

Works Cited A.G. "Egyptomania." Life, 19 April 1923, p. 13. "An Egyptian Mummy." Life, 27 July 27 1922, p. 10. "Arthur Little Takes a Trip 'Up in the Clouds.'" Judge, 1 April 1922, p. 14. "Aut Scissors Aut Nullus." Life, 31 May 1923, p. 28. "Ballad of Puzzled Husbands." Life, 16 October 1924, p. 12. "Carl S. Shoup; Set Up Japan's Tax System." Los Angeles Times, 1 April 2000, n.p., latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2000-apr-01-mn-14878-story.html "Chicago Vaudeville Shows." Variety, 10 February 1922, p. 8, archive.org/details/ "The Daily Papyrus." Life, 19 April 1923, p. 20. "Kyra at the Winter Garden." Unregard Oblique, unregardoblique.com/2020/10/03/ "Cutting Off the Last Word." Judge, 29 April 1922, p. 26. Eaton, Walter Prichard. "Croton Water Versus Crime." Judge, 21 July 1923, pp. "Egyptian Papers Please Copy." Judge, 10 November 1923, p. 19. Elton, Martha Gage. Bertram Hartman (1882-1960), An Early Modernist from Kansas. "Everyday Behavior." Life, 7 August 1924, p. 32. "Faro and Bridge." Judge, 9 December 1922, p. 19. Folwell, Arthur H. "Princess Mary's Baby." Judge, 31 March 1923, p. 3. "Fragment Depicting Incidents During the Reign of Nor-mal-cy I." Life, 19 April 1923, Glithero-West, Lizzie. "Tutankhartier: Death, Rebirth and Decoration; or, Tutmania in the 1920s as a Metaphor for a Society in Recovery After World War One." Ancient Egypt in the Modern Imagination: Art, Literature and Culture, edited by Eleanor Dobson and Michola Tonks, Bloomsbury Academic, 2020, pp. 127-144. Grant, Thomas. "Judge." American Humor Magazines and Comic Periodicals, edited by "Gridiron Aesthetics." Judge, 20 October 1923, pp. 14, 30. "Heywood Broun." Brittannica, britannica.com/biography/Heywood-Broun Hill, W.E. "As We Were Saying: Nature Studies." Judge, 24 March 1923, p. 26. Hubbard, George H. "A Lay of Ancient Egypt." Judge, 31 March 1923, p. 3. Keith Preston Papers. Modern Manuscripts & Archives at the Newberry, archives.newberry.org/repositories/2/resources/305 "King of Fashion." Poiret, poiret.com/en/brand/paul-poiret/le-magnifique "King Tut Deco Egyptomania." Pinterest, www.pinterest.com/mspatricialynn "King Tut Good Luck Ring." Judge, 22 September 1923, p. 25. "Kyra, Oriental Dancer." Fall River Globe, 20 November 1922, p. 4. Lewis, Tracy Hammond. "Twin Bed-Time Stories: Benedict Learns of the Lewis, Roger. "Old King Tut Was a Wise Old Nut." Lyrics. Internet Archive, archive.org/details/b10236211/page/n1/mode/2up Life (Cover). 19 April 1923, n.p. Marschall, Richard E. "Life." American Humor Magazines and Comic Periodicals, "Modernity." Judge, 14 April 1922, p. 31. "Meanwhile." Life, 8 March 1923, pp. 14-15. Mott, Frank Luther. "Judge." A History of American Magazines: 1865-1885, vol. 3, "Mrs. Tut-ankh-Amen." Life, 31 May 1923, p. 28. Mueller, Tom. "The Discovery That Almost Wasn't." National Geographic, ---. "The Discovery Timeline." Archeology Archive, 25 March 2005, archive.archaeology.org/online/features/tutwatch/timeline.html "Mummies that Move." Judge, 8 April 1922, p. 14. Nielsen, Nicky. Egyptomania: How We Became Obsessed with Ancient Egypt. "Pharaoh’s Pharmacist." Judge, 4 March 1922, p. 6. Preston, Keith. "The Latest Crime Wave." Judge, 10 March 1923, p. 9. "Prof. Hammond to Retire." New York Times, 24 May 1930, p. 3. Root, E. Merrill. "Antiquity." Life, 3 August 1922, p. 6. Shoup, Carl S. "What We May Expect from the Egyptian Tomb." Judge, Sivac, Alexander. "Egyptomania!" Getty, https://www.getty.edu/news/egypto "So Rapid Is the Fad." Judge, 24 March 1922, p. 26. "This is Kyra." Judge, 25 February 25, 1922, p. 15. "Tracy Hammond Lewis." The World Biographical Encyclopedia, prabook.com/web/tracy_hammond.lewis/1039548 Traprock, Walter E. (George S. Chappell). "An Egyptian Episode." "Tut-ankh-Amen" in "Aut Scissors Aut Nullis." Life, 31 May 1923, p. 28. "Tut-ankh-Amen" in "Life Lines." Life, 5 April 1923, p. 12. Up in the Clouds." Internet Broadway Database, ibdb.com/broadway-production

|

Journal Home

AmericanPopularCulture.com