New Hollywood to Blockbusters:

Tracing Edits in Raiders of the Lost Ark

Americana: The Journal of American Popular Culture

(1900-present), Spring 2025, Volume 24, Issue 1

americanpopularculture.com/journal/articles/spring_2025/mendoza.htm

San Francisco State University

|

IntroductionActions and reactions. These are foundational units of motion picture editing operations in the Hollywood tradition. The shots chained into a movie's scenes relate as a presentation and analysis of spatiotemporal events, with the cut from one to another informed by characters' visible responses to stimuli in their surroundings. Sergei Eisenstein theorized this process with D. W. Griffith's films early on, as did David Bordwell and Kristin Thompson later with classical period films. Whether enlarging a detail, or juxtaposing a frame and its diegetic reverse, actions were attentively monitored in this screen experience, impacting the pacing and ideas transmitted. By the mid-twentieth century, the seamless Hollywood studio editing style grew stable, repetitive, predictable, and stale while a series of independent productions deviated from narrative and formal conventions, experimenting with, among other aspects, editing. In the 1970s and early 1980s, a surge of New Hollywood blockbusters involved filmmakers whose productions carried over to the mainstream and contributed to Hollywood's revitalization. Among them was Steven Spielberg, whose 1981 directorial effort Raiders of the Lost Ark, from writer-producer George Lucas for Paramount Pictures, captivated audiences and earned Michael Kahn's editing an Academy Award. The film's success invites inquiry into the editing techniques it used to connect with viewers. This article examines Raiders through its creative context, narrative construction, and formal strategies to explore how the film integrates measured pacing alongside fast-cut action, offering a more organic progression of story and spectacle than the conventional Hollywood studio edit.

Synergy of OppositesEmerging on the tail end of the New Hollywood period, Raiders of the Lost Ark announced the arrival of the Blockbuster Era. Thomas Schatz describes this moment in cinema history as "the first period of sustained economic viability and industry stability since the classical era" with motion pictures such as The Godfather (1972), The Exorcist (1973), American Graffiti (1973), and Star Wars (1977) initiating an era of big budget productions that drew massive audiences to theaters (9). Spielberg was part of this zeitgeist, with hits like Jaws (1975) and Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977). While Schatz points out that the New Hollywood was not as stable or unified as its classical predecessor, several cultural conditions unite the films. For instance, as he notes, film courses began being offered in colleges – an indication of a greater film literacy in new generations, aware of and building off a cinematic past. Another example is the decline in attendance of a so-called "general public," which called for the targeting of niche markets, particularly if they tended to be active moviegoers, like teenagers. The break of the Hollywood production code and emergence of the rating system in 1968, segmenting the wide undifferentiated public, was leading to further experimentation on the part of moviemakers who exposed audiences to shocking content. While rated PG, Jaws exemplifies one kind of shock narrative. Schatz describes it as a chase film and an emotional rollercoaster with an edit and score that is "precisely and effectively paced, with each stage building to a climactic peak, then dissipating, then building again until the explosive finale" (19). This description applies to Raiders too, as an adventure that is constructed by an increase in tension through an acceleration and then a release of it. The movie, in this sense, fits in a trend Schatz describes as film narratives becoming "increasingly visceral, kinetic, and fast-paced" (25). However, the contrast to these attributes – intellectual engagement, repose, and slowness – is also always at play. The adventure story that Raiders of the Lost Ark proposes relies not just on present events of characters moving around locations and interacting with allies or antagonistic peers. Rather, it is set in and subsequently explores a bygone timeframe – 1936 – that tackles a further removed past of the world, which assumes a Western civilization point of view. Spielberg reflects on how the objects that characters are involved within the Indiana Jones series symbolize the impulse of storytellers to "reach into the imagination of what really has existed in history, and even in mythology, and bring that to modern-day audiences" (qtd. in Bouzereau, Iconic). This temporal distance between the storytelling and its fictionalized source event is recurrent in Lucas's works such as THX 1138 (1971), American Graffiti, Star Wars, and the more recent Red Tails (2012), produced by Lucasfilm. The narrative bridge proposed across these works frames the adventure as a process of uncovering a long-gestating mystery. Both characters and spectators must navigate temporal distance and delay, as answers are neither immediate nor easily obtained. Michael F. Deters asserts that Raiders' contents and form were meant to serve an intertextuality with mainstream cinematic traditions that preceded it. Aligning the movie with a postmodernist cultural stance that reconstructs and celebrates a status quo instead of deconstructing and opposing it, as some previous New Hollywood films did, Deters identifies the movie as a pastiche work. He states that Raiders achieves this effect as it "enable[s] the viewer to partake in a sort of game" in which "the viewer's active role in meaning-making results in the satisfaction of achieving a seemingly 'higher level' of interpretation" (i). This shift toward spectator participation entails that the intertexts – visually stressed over a shot or series of shots – need a sufficient amount of screen time, at minimum, to be identifiable, with inserts of short duration potentially lending themselves less to this effect. At the same time, the movie's pacing must still work for the viewer unversed in said prior cinema. Deters sees the movie manifesting a nostalgia for traditional narratives of a simpler past, which echoes a political response to the socioeconomic anxieties of the time. He argues that Indiana's characterization, embodied by actor Harrison Ford, seeks to "fulfill the audience's need to (1) relive memories of similar, earlier male characters and in turn (2) believe that such men ever existed" (5-6). This perspective addresses spectators long acquainted with on-screen depictions of such characters – Schatz's film-literate generations – but it also connects to viewers who may not have seen prior movies or shows, but nonetheless relate to a mythical truth: that of a clear-cut hero of action and a world that can straightforwardly and thoroughly reveal itself to them. In the movie's aim to cultivate rather than interrogate "the power that the medium hold[s] over its audience," Deters points less to the 1930s serials that influenced Raiders' "breakneck action and pacing" and more to the display of simplified character types (40, 6). This cultivation informs the edit, in its less accelerated moments, not just in opening up an interval to evoke prior film experiences, but to explore diegetic space and time. Examples may be found in usages of long takes, but the governing trait is a cutting approach that gently threads expectations, delays, subversions, and payoffs. Upholding the cinematic work's influence over the spectator's intellectual and affective engagement thus involves a withholding of information. These exploratory possibilities that the edit of the movie allows were not, however, deliberately at the forefront of its moviemakers' intentions. Bruce Green, who was assistant editor to Michael Kahn on Raiders, asserts that there were no discussions among the team regarding leaving moments for audiences to immerse themselves in the world of the story which briefly paused or took a detour from the progression of the narrative's events. Any perception of such moments should thus be understood as a byproduct of storytelling-centered strategies. The above considerations on the experiential package that Raiders was built to provide cannot be made losing sight of the film business trends and demands materializing in the 1970s. David Cook, for one, mentions market research as a practice that was done to determine "what the public wants to see" (15). The response to Jaws and Star Wars was not lost on the departments that were handling Raiders, with the movie being promoted as coming from the creators of such cinematic hits of the last half decade. This implies that the moviemakers, as part of a broader entertainment tendency, set out to double down and deliver on the elements that resonated with audiences in past successes. If Jaws was identified with a build-up pace and Star Wars with an unrelenting one, as Schatz suggests, Raiders was poised to be presented as a cinematic experience combining both through the edit. But Cook also refers to the movie, along with 1978’s Superman: The Movie, as a "bubble gum" blockbuster, which targets audiences under twenty-five years old and is mainly an action-adventure (23). Not unlike Superman, a movie based on a story and character that had circulated in audiences for decades but was aiming at newcomers, Raiders had to offer but also stand on its own in its combinations of past efforts. The reconfiguration of character types needed to walk a fine line to be favorably compared with predecessors and to gain its distinct identity. The popular films of the 1970s and 1980s returned to the "performative spectacle" of early film, termed the "cinema of attractions" by Tom Gunning, where direct sensory stimulation was a fundamental part of spectatorial pleasure (Cook 43-44). These primal movies acknowledged the spectator through the exhibition of visual tricks for the camera. Gunning himself recognizes this point, in proposing that "in some sense recent spectacle cinema has re-affirmed its roots in stimulus and carnival rides, in what might be called the Spielberg-Lucas-Coppola cinema of effects" – a milder version of the attraction, more baked in a story-world (70). Cook's quote of Stephen Farber that movies were a circus form before a storytelling or an art one, as well as the typical carnival ride's feature of speed and strolls, further emphasizes the actuality and sense of unpredictability an experience like Raiders was to carry, even if it had an overt narrative and functioned through a hero. Noël Carroll describes Raiders, influenced by films like Star Wars and Superman, as extravagant examples of genre memorialization through imitation and exaggeration. He refers to "plot implausibilities – Indiana Jones hops on a submarine without worrying whether it will submerge – and its oxymoronic, homemade surrealist juxtapositions – the Nazi Army led by the Hebrew Ark of the Covenant" ("Allusion" 62). In line with the circus attraction and the wondrous is the hyperbolic, rooted in the very depiction of good and evil, accentuated in the cutting and sound elements. For Carroll, representational techniques like the above were examples of a "shift away from an understated, 'classical' realist style toward expressive stylization [which] is uneven and sporadic, popping up here and there" ("Allusion" 78). He refers to movies that "painlessly integrated, while muting, European innovations" and specifically Mike Nichol's The Graduate, released in 1967, as a use of "fancy match and shock cuts" (78). While Raiders is more grounded in the classical Hollywood style, it nonetheless achieves matches and shocks through the expressiveness of juxtaposed visual and aural images while going through the motions of covering the perspectives of a scene. Within a sequence, for example, Indy, about to run out of a temple after barely escaping a descending door, unexpectedly collides in the foreground – through a slight reframe tracking him left – with the body of his traitor companion who has been pierced by bars, nine minutes into the movie. Across two consecutive shots, there is the close shot of a Nazi henchman noticing a plane propeller approaching his face, followed by a cutaway to the plane's tail fin as it is sprinkled with blood at the eightieth minute. These sequences achieve, respectively, opposite cinematic approaches to reality: Andre Bazin's spatial unity that makes the movie an "imaginary documentary," and Sergei Eisenstein's generation of ideas through the "cinematographic conflict" or counterpoint between two shots and the qualities of their contents (46; 39). In the first case, the impact is emphasized through keyframes in the same shot and the moving camera coming to an abrupt stop; in the second, it is the brisk and blunt presentation of an event – the henchman being brutally shredded – through the very omission of the literal visual moment, left to be inferred and exist virtually between two shots and in the spectator's imagination – likely influenced by Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho (1960). In a separate piece about repeat audience affect, Carroll also mentions Raiders as an example of a successful suspense film. He sums up suspense as a response to fiction:

Carroll's theory, which again refers to exaggerated opposites, breaks down Raiders' pace more precisely than its reputation of nonstop action does, applying to situations quick and slow in the movie, to scenes, and to the work as a whole. It particularly draws attention to the more temporally gradual progressions, like the discovery of the Ark's hideaway in the fiftieth minute. This view of suspense shows the basis of a narrative complexity, which Warren Buckland argues (against claims from the time) is not traded for a chain of spectacle on Raiders as a New Hollywood blockbuster. For New Hollywood directors, Warren Buckland states, "a variety of compositional norms exists for exploitation. These include: the selective quotation of Old Hollywood films, the visual rhetoric of comic books, the norms of television aesthetics, and the compositional norms of European art film and the avant garde" (169). Buckland uses the example of Raiders' bar fight to identify the rapid cutting and close-ups inherited from television, but asserts that the storytelling, placing story first, defines Spielberg's style. Kristin Thompson, in her interrogation of the notion of post-classical filmmaking in which she sees contemporary Hollywood productions for the most part still adhering to the narrative strategies of the studio era, identifies a variation which affects movies like Raiders. She cites Richard Maibaum, screenwriter of the early James Bond movies, arguing that the latter began the "larger-than-life approach to action-adventure pictures," Raiders being, besides its "wonderful gimmick (the ark itself), a kind of Bond picture. The action, the villains, the unexpected!" (305). Maibaum, cited by Thompson, describes Bond moviemaking as increasing the number of bumps in a movie, describing a bump as "something like someone says, 'I'm looking for a man who has a short index finger,' and a totally unexpected guy says, 'You mean like this?'" (305). These are the kinds of bumps that Raiders accentuates, and as Thompson reasons in understanding bumps as "important plot twists, whether they are quiet but dramatic revelations or more action-oriented moments," their location is not only during the action-heavy sequences of the adventure, but during scenes that, in a more paused way, push the story forward (305). The dramatic impact results from the implications for the characters as they explore the world of their quest, going beyond mere cinematic exposition and rather paying off and heightening ideas introduced earlier on. Little public information exists about the editing process of the movie and its approaches. In a 2014 talk for the Manhattan Edit Workshop, editor Michael Kahn recalls some of the experiences from the assembly of Raiders, such as his work around the escape from the Hovito temple scene when Indiana Jones is faced with getting past the exit of an area before it is sealed by a wall coming down. Kahn voices his challenge at the time as being to achieve his desired pace while dealing with the risk of drawing attention to the fact that the wall appeared at a still higher place when going from one shot to another, to highlight a character action moment. Though the precise way Kahn worked around this issue is demonstrated in the final edit of the movie, the ultimate reason for each cut around the scene remains unclear. What it does suggest, though, is that the initial intention for the movie, barring its long takes, was designed and executed with a snappy pace that may have required slowing down in post-production. Strategies include the cutting-in-camera approach of Indiana's first reveal in the jungle, which frames specific moments in the action: the quick cutting between these contributes to a frenetic unfolding of an event with multiple parts, but the coverage of different aspects of this event across shots extend time, in a sense, and even if ever so slightly. According to Kahn's assistant editor, Green, the first cut of Raiders ran long, not because it used slow cutting, but because there was so much great material captured, citing the truck chase as a sequence with extra moments that were ultimately excised. He bases his claim on the notion that it is incumbent on an editor to deliver the director the film they shot, before removing any material. Only after screening the first cut to Spielberg and realizing its length would Kahn and his team trim it down. Green defines the internal rhythm across the movie never too fast or slow. In a 2011 interview with David Poland, Kahn mentions the Raiders movies as having a sense of comedy, which he was experienced in cutting from editing the television show Hogan's Heroes for six years of his early career ("DP/30: The Oral History of Hollywood"). Editor Saul Pincus interprets the comedy label as "another way of saying [Kahn] cuts for the set-up of the gag and the impact of the follow-th[r]ough, whether that's for a punch, a laugh, or a mine car jumping th[r]ough thin air" (qtd. in Coate). Pincus sees the gag and payoff as applicable to both inherent comedy and the overall staging and cutting structure, arguing that what makes the original three Indiana Jones films "work as 'audience films' is that the concepts of action/reaction and dramatic reversal are present" (qtd. in Coate). This extra-comedic timing can be understood as suspense and is a more productive framework to understand how the movie immerses viewers. James Mairata observes the French New Wave influence on Spielberg – made manifest in his casting of Francois Truffaut in Close Encounters of the Third Kind – besides classical Hollywood and directors' style (42). This alignment can be understood in the movement's insistence on allusion, as Carroll states, more than faithfulness to style ("Allusion" 72). Techniques like long takes and shocks, for one, are not respectively shortened or induced via jump cuts, but worked around using continuity and shot, reverse-shot editing. As David Bordwell observes, "Kuleshov and Pudovkin identified the shot, reverse shot arrangement as incorporating 'reminders' of spatial orientation in that they repeatedly reveal the same space and objects. Each successive shot reconfirms scenographic space for the spectator using cues" (qtd. in Mairata 84-85). This point implies, for Mairata, that Spielberg "is always mindful of the 'needs' of an audience of constructing a narrative that maximises audience impact and affect" and that "continuity is a crucial element that must be observed at all times if the spectator is to fully 'accept' the 'world' of the narration" (68, 98). Addressing the public extends to not losing viewers on the perception of pacing, neither too fast nor too slow for the actions depicted across shots and within one. Mairata brings up the fact that jump-like editing only happening in Spielberg's films due to prior acceptance in classical Hollywood, an example being axial cuts, which Raiders uses twice. On Spielberg's criteria, Mairata refers to his aim for geography, or knowing where in the setting and screen his characters are; his non-conforming to television and classical Hollywood's "close-up, two-shot, over-the-shoulders and master shot" formula by using reverse masters; and his preference to do master shots and edit in inserts as coverage (85, 88). Spielberg's attention to masters instead of close-ups for audiences to have an overview and be "their own film editor sometimes" contrasts with his contemporaries, as Mairata notes with the intensified continuity trends pointed out by Bordwell, where the increasing use of tighter shots has led to a "corresponding decline" of masters and establishing shots, along with "quickened editing" (89, 90). Citing Kahn, Spielberg shoots substantial amounts of coverage to have options to mediate the useful parts of his masters. A strategy Mairata poses that allows Spielberg to cover a scene in a single shot, multiple shots, or master shots, either in short or long duration, is two-plane composition or deep space staging, where there is activity in the foreground and background of a shot. Mairata uses the example of Indiana running in a single shot from background to foreground at the fortieth minute (115). Mairata aligns Spielberg's "deep space editing" with the choices of Bazin, Eisenstein, and William Wyler (139). Wyler believed that deep spaces and long takes allow viewers their own cutting, and Bazin, that it permitted a simultaneous presentation of wide and close shots. Mairata concludes that the constant use of a wide reverse, of which the jungle sequence in Raiders is an example, helps create "mostly 360-degree scenographic perspectives that suggest a 'complete' world of the scene," operating in a variation of the classical shot, reverse shot that transcends dialogue scenes, prioritizing the syuzhet, preserving an "invisible" style, and effecting "a narration seemingly of itself and without authorship," which "reinforces the perception of the scene as complete and existing as a self-perpetuating event" (186). In terms of editing style, Green recognizes continuity editing as the system Kahn was employing, stating that Raiders should not be considered as an example of cutting-edge editing techniques or breaking rules, as the goal was to completely engage audiences, which meant using the codes they had been presented with at large in moviegoing experiences. He states that there is nothing in the movie to disorient audiences from the experience of watching it. In his research on the contributions of Kahn to Spielberg's work, Konstantinos Papathanasiou focuses on identifying the editor's role in Raiders, considering that the majority of the movie was storyboarded in pre-production and relied on the cutting-in-camera technique. Examining Warren Buckland's claim of Spielberg's monster movies and Raiders having "an off-screen presence in every sequence which takes different forms, generates and increases the suspense level, and reaches its cinematic climax in the last sequence," Papathanasiou analyzes scenes from the South American jungle introduction, the bar fight in Nepal, and the opening of the Ark, in which Kahn's editing "maximizes the impact of this presence" (33, 39). Papathanasiou finds that "Spielberg relies on Kahn to find the pace and rhythm in his shots, especially, when coverage is not available" and that "[t]he slow editing preludes something and/or someone that their revelation will wreak havoc, and will be experienced through rapid editing that offers, though, clarity of narrative" (48). It is important to clarify that while the cut-in-camera technique serves specific inserts or series of inserts, Hollywood productions are broadly shot through camera setups spanning the entirety or a significant part of a scene, whether it is a wide master or closer coverage, which is where work like Kahn’s becomes key, in determining the narrative beat at which to cut from one shot to another. Although the storyboard and cutting-in-camera approaches in the movie's production have been well documented, their specific role in the editor's process has been largely overlooked. Kahn has stated that a "storyboard is not for me, it's for the people on set...Steve and I will examine the film on the KEM and decide which takes or pieces of takes we want to use and he and I will collaborate. We'll put the scene together without storyboards" (qtd. in LoBrutto 172). Green corroborates this point by stating that no shooting strategies of the kind were taken into account during post-production, with no storyboard visible at all in the post-production area. As per Green, Kahn would periodically sit with Spielberg during production to watch the most recent dailies, with an assistant taking notes based on their conversation. According to the assistant editor, Kahn would request dailies to be screened in story order, meaning to start with the takes of the widest shot covering a scene from one direction, followed by those of its reverse, and then moving to the same procedure with closer shots. By doing so, Green argues, in contrast with the more standard practice of watching the dailies in shooting order, the conversations between director and editor would become more immediately centered on editing. When not in a theater, recounts Green, Spielberg would watch the dailies on a flatbed editing machine, draw a sketch of what the shot looked like and write some notes, such as which segments of the shot he would like to use, going through all the takes. He would then study the notes on his own before handing them over to Kahn, giving him guidance on how to cut, in terms of what shot to start with and which one to go to next. It was when encountering a Spielberg-advised cut from one shot to another was not possible due to discrepancies in continuity that Kahn would have to make changes for shots to flow seamlessly. The aforementioned process reveals the practical association between a sense of story order and the coverage of a scene from a general set of elements to its particular ones, editorially represented as starting with wider shots before moving on to closer ones. This workflow helps establish scenographic space early on, the memory of which lingers as a point of reference audiences can situate subsequent shots with, and which aids their immersion and settlement into the story world. Integral for the audience experience of Raiders of the Lost Ark is the score by John Williams, whose orchestral compositions vary the intensity and velocity of a number of themes and motifs. The impact of this domain in the picture edit is, however, less significant. In an interview with Adam McDaniel, supervising sound editor Richard L. Anderson recounts how sound designer Ben Burtt prepared a temp dub for a screening to Lucas and Spielberg with "a few key effects that were necessary to tell the story and mixed them with the temp music that Michael Kahn (the picture editor) cut against to help determine the pace with all the silent material. The truck chase had only a few gun shots and crash impacts with a lot of music." Green contests the extent and effect of the aforementioned practice, acknowledging Kahn's internal sense of rhythm that, with the nature of the story and shots, dictated his choices of determining the overall flow of motion in a scene. Providing more context, Green states that Spielberg wanted to see scenes with music and that Williams, with his knowledge of classical music, would make the temp track recommendations, one of which was Rossini's William Tell Overture for the truck chase. Kahn had already edited the scene, and only made minor adjustments when he placed Rossini's piece in. While the visual synchronicity may have been partly determined with precision by music, it first needs to be examined on its own. Anderson also recalls Kahn saying "that he doesn't worry about matching everything perfectly from cut to cut. It is the overall flow and pace of the picture that matters" (qtd. in McDaniel). An example in the thirty-ninth minute is the cut from a wide shot of Marion running through a dark entrance to a tracking shot of her, running across a brightly lit corridor. This edit offers the insight that in order to advance the story and explore the world around it, whether in a slow or quick moment, the reliance is chiefly on items that are in motion rather than on those that are static. The example is also useful to further comprehend Kahn's often repeated reflection that he does not approach the edit from knowledge, but from feeling, with each shot having a purpose and causation from and towards another, which suggests these are bound formally by a continuity of movement more than a strict match in positions and directions (qtd. in LoBrutto 172-173). Kahn recalls his director's mindset as shooting for the edit, reflecting: "I had a lot of coverage...Sometimes it needs just a little touch. It needs another beat. Or it's a beat too much. It's all very sensitive" (qtd. in Bouzereau, The Making of). The emotional impact as well as the timing of setup and payoff is thus the cut's driving force. The preceding literature provides cardinal points to map out the edit of Raiders of the Lost Ark. There is a brisk action-driven framework for assembling a cinematic story towards which a more discreet, still dramatic and spectacular force operates, one that plays with expectation delivery all the while navigating the spatiotemporal setting of the diegesis. Raiders thus functions as it does not only due to its quick cutting but also due to a slower one that balances it, reconciling a dominant impulse of cutting to the chase with an approach that is willing to linger on the raw visualization of an event. This style needs to be quantified to better understand its nature. The theorized interplay of cutting is initially found in a dichotomy of action scenes and dialogical developments or expositions. But it also manifests through a kind of scene that, rather than focusing on dialogue or many actions of characters, has one or a few of them performing a single main task as they contemplate the world surrounding them. These scenes are not wholly passive, nor reducible to long takes, but deaccelerate the dominant modes. They can bring the revelation of an insight to a character or characters while withholding a final knowledge that launches them further into uncertainty as they continue to navigate the world around. What follows is an analysis of the editing strategies in Raiders of the Lost Ark, with particular attention to a sequence that exemplifies the type of cinematic moment previously described: the map room scene. Positioned near the film's midpoint, runtime-wise, this scene constitutes a self-contained event with a discernible temporal beginning, middle, and end. Although real time may be compressed through intercutting, the editing does not foreground this manipulation. The scenes that bookend it suggest more significant temporal ellipses, further distinguishing the map room moment. While not unique in this respect, the scene's structure and relative isolation from surrounding narrative threads make it a particularly useful case for examining the film's cutting patterns.

Notes on CinematricsIn 1974, as recounted by Mike Baxter, Barry Salt developed the concept that Yuri Tsivian calls cinemetrics, defined as "the statistical analysis of quantitative data, descriptive of the structure and content of films that might be viewed as aspects of style" (Baxter 1). This analysis has typically centered around the calculations of average shot lengths (ASLs). Stressing the purpose of comparisons with the data to recognize patterns, Baxter sums up points in the debates about cinemetric data: the pattern of decline in average shot lengths since the 1950s, and the average shot lengths of US movies being more concentrated in shorter values than European movies between 1918 and 1923, which are more varied and thus embracive of longer lengths. Baxter explains a point of contention regarding whether the average or median shot length should be selected for analysis. I agree that, while average shot lengths have their use in obtaining a first impression into the editing trends of a movie, they do not provide sufficient information to understand how these behave, or vary, within the runtime, much less what style of rules they may obey. Studies focused on editing have been elusive due to commercial confidentiality or phenomenological reasons. Cinemetrics is a step in the direction of retracing a sense of the thought process behind cinematic editing practices that filmmakers often explain as simply "intuitive," as Greg Loftin reports, in terms of responding in agreement or dissent with a set of perceived conventions (86). Salt, quoted by Baxter, sees the ordinary use of cutting rate variation in the convention of more cuts for scenes with more dramatic tension or action. Using statistics but looking to go beyond them, what follows is the methodology used to breakdown Raiders with procedures similar to those used by cinemetrics, which has an entry in its online database with a graph of shot versus length, as well as calculated average and median shot lengths, to approach the movie in a way that mimics its pragmatic, arguably empirical viewing by both editors and spectators.

MethodologyA digital file of Raiders of the Lost Ark in in full HD resolution and a rate of 23.976 frames per second was run through the DaVinci Resolve software's Scene Cut Detection for an automated shot breakdown, manually verified and adjusted for cuts not identified or incorrectly identified, for instance, due to light or framing variations within a shot. 1454 shots were counted over a runtime of one hour, fifty-five minutes and eleven seconds, including opening and closing Paramount logos as well as the credit roll. Digital playback raises questions of compatibility with its original film format, which had a slightly different rate at 24 frames per second. This issue is not one of the research aims, as Raiders has been widely disseminated non-theatrically since its release.

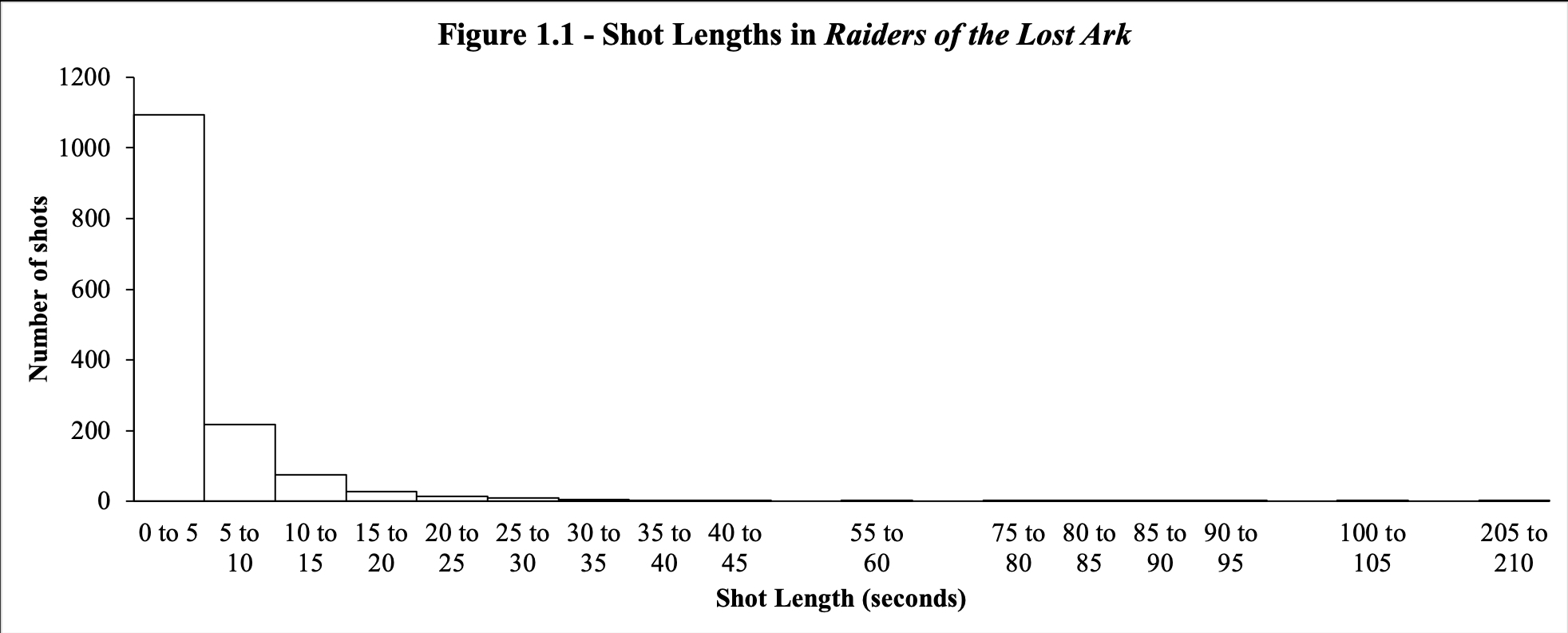

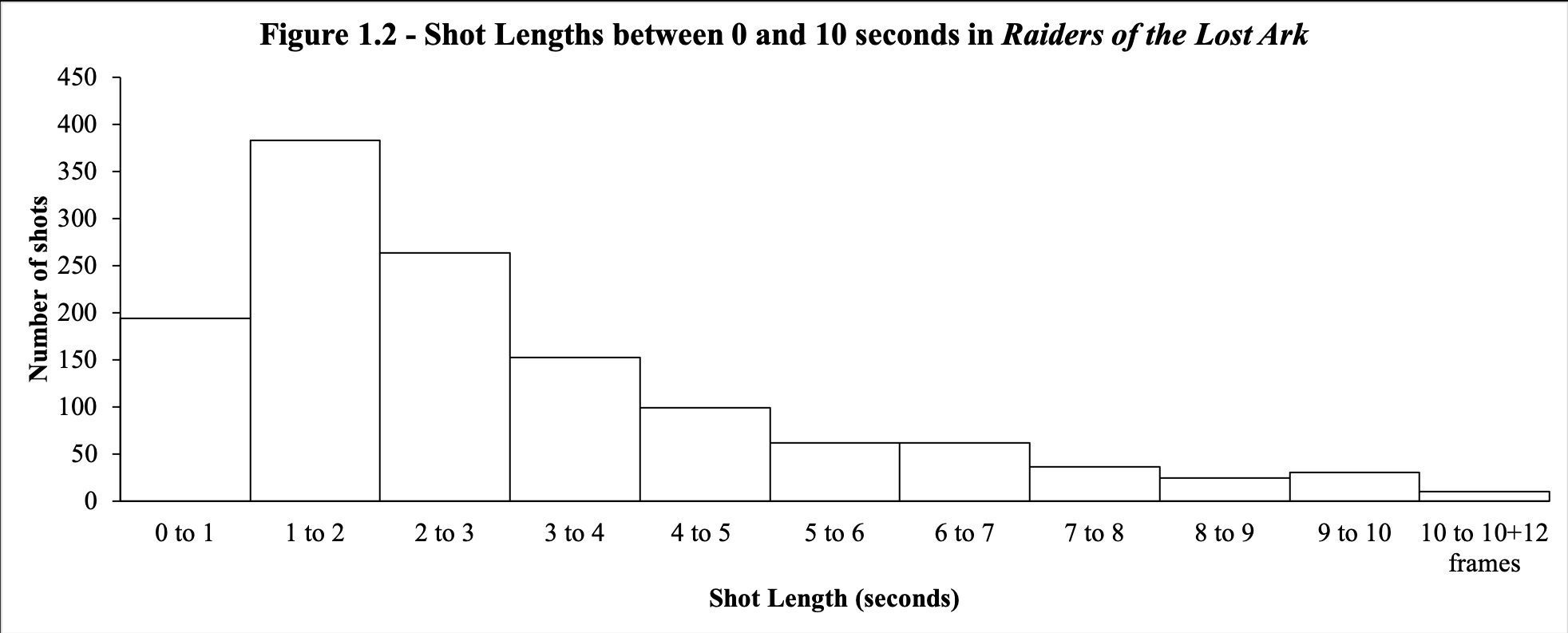

Analysis: Part 1: The MovieShot Length. 1093 out of the 1454 last between zero frames of picture (four being the actual minimum) and almost five seconds (four seconds and twenty-three frames), as shown in Figure 1.1. The results also show 217 shots towering the rest of other ranges, between five and ten (nine seconds and twenty-three frames) seconds. The two ranges amount, then, to approximately 90% of the movie, initially suggesting a strong reliance on shots of short duration. An enlargement on this sample of the shots, displayed in Figure 1.2, reveals that 383 shots – over a fourth of those used in the movie – last between one and two (one second and twenty-three frames) seconds, followed by 264 shots lasting between two and three seconds (a sixth of the total), and 194 lasting between zero seconds and one second. Despite the reliance on these shots of short duration as an editing asset, it is important to evaluate how they are used in screen time. In this sense, the shots that last between zero and five seconds amount to thirty-eight minutes of screen time while those between five and ten seconds total twenty-five minutes. Together, these runtimes comprise between 54% of the movie (57% when not considering three minutes, twenty-nine seconds and twenty frames of end credit roll). This data lines up closely with the average shot length for Raiders of the Lost Ark being between four and five seconds, according to the Cinemetrics website, but also displays the limitations of drawing conclusions from this number: the actual number of shots in the movie between four and five seconds is ninety-nine, representing only 7% and likewise taking just seven minutes of the total runtime.

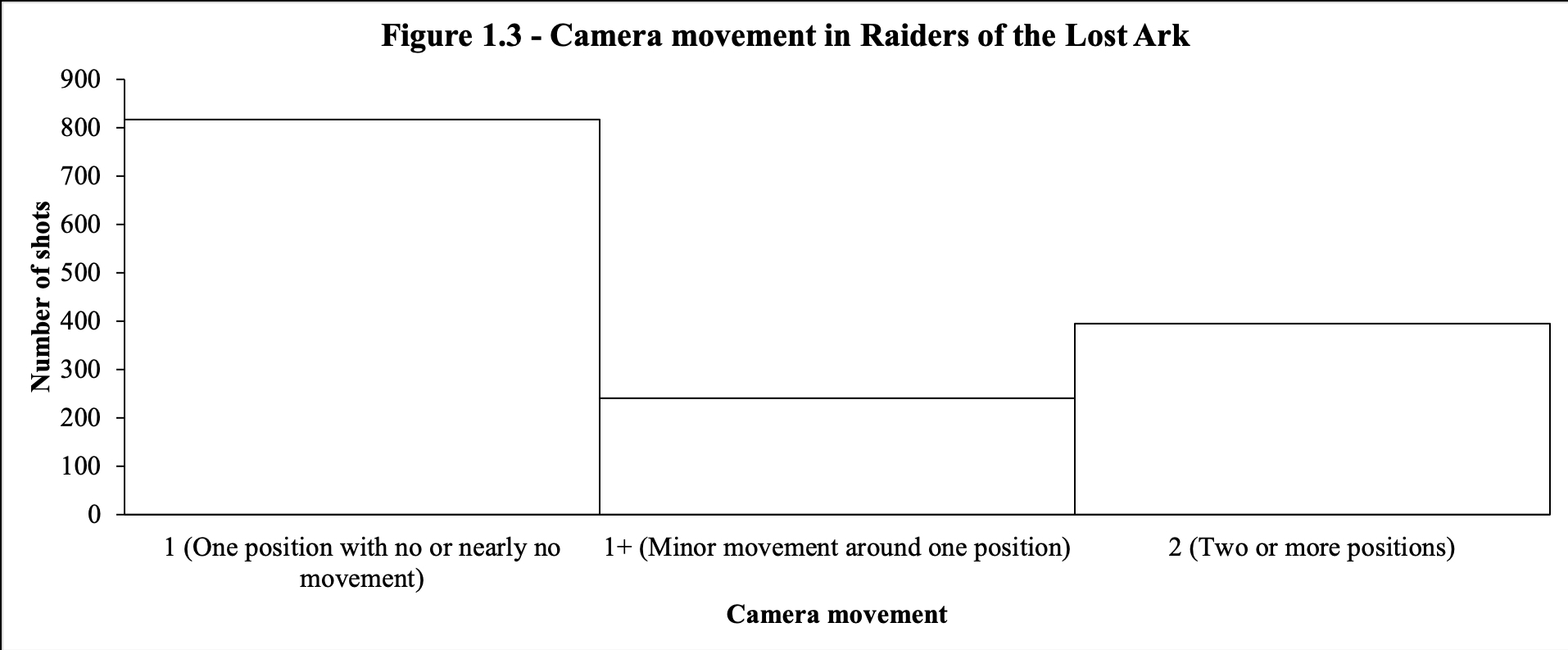

Camera Positions. Among the most salient observations, 817 out of the 1454 recorded shots had a single camera position with no or barely noticeable movement, amounting to approximately 56% of the shots used. Furthermore, 241 (17%) of the shots had minor movement, and 395 (27%) moved between two or more camera positions. Adding the first two of these numbers to 1060 (or 72%) suggests the edit's preference towards single keyframes to display the action of the movie.

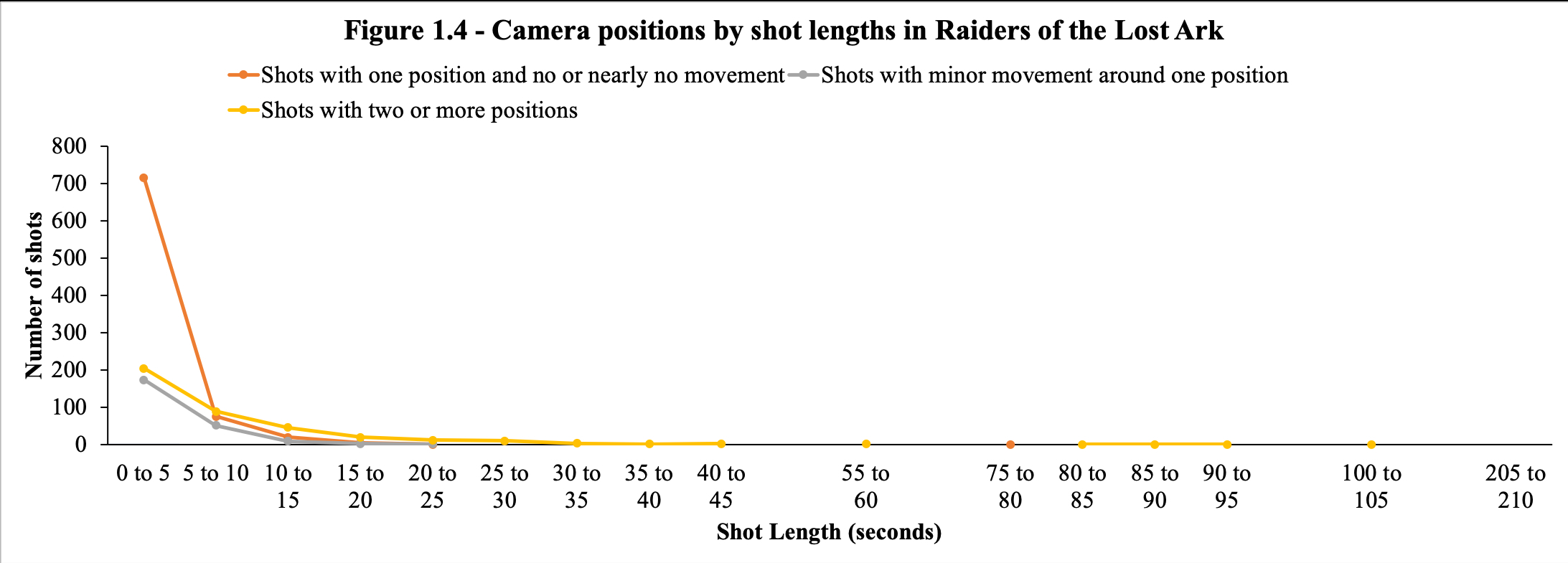

Out of the shots lasting up to five seconds, 715 (81% of 1093) have no or very minor camera movement, as noted in Figure 1.3. As thirty of the thirty-eight minutes displaying shots of such duration, this fact suggests a major importance given to providing clarity of geography than adding camera-responsive kinesis to the action of the staged adventure story. Out of the shots lasting between five and ten seconds, 128 (59% of 217) have no or very minor camera movement, totaling fourteen out of the twenty-five minutes these are used in. This initially reveals a change in the correspondence between shot length and camera movement in which duration of action encourages changes in framing (and vice versa), as explored in Figure 1.4. Still, the grouping of the aforementioned shots as the predominant range of zero and ten seconds, 843, results in over half of the movie relying on these (time-wise, the sum is of forty-four minutes, so more than a third but less than half of the runtime). From this data, then, we can pose the conclusion that the most common shot used in the movie is the one of a single camera position with nearly no movement and does not exceed ten seconds.

If the rest of shot length ranges are analyzed, a visible trend emerges in which, as the duration of a shot increases, the use of two or more camera positions becomes dominant. In fact, the shots with one camera position and no or nearly no movement, as well as those with minor camera movement around one position, disappear in use from the twenty-five-second clip onwards. Thus, if any shot lasts more than twenty-five seconds, camera movement is needed to justify its duration. There is one exception: a shot using a single keyframe with little to no movement, reflecting one minute and nineteen seconds of screen time. In this shot, the camera is not completely static, but does subtle readjustments, tracking the characters' motion. A fully static camera, whether or not intended from the planning stage, provokes – through the person operating it – a somewhat participatory role. The shot in question frames the majority of the conversation between Indiana Jones and René Belloq (Paul Freeman) at a bar in Cairo, following the apparent demise of Marion Ravenwood (Karen Allen) (timecode 44:03:20 to 45:23:15). In this two-shot close-up, the camera sits almost ready to respond to any offsetting action that happens in the shot, only decidedly following Indiana through a tilt up as he speaks and moves his head slightly upwards in doing so, then panning left to Belloq as he leans towards Indy, as well as tilting down when he opens his eyes emphatically. The shot, captured in Figure 1.5, thus remains an exception and breaking of a rule, though strategically framed to capture the reactions from both of the main characters in the scene and offering tension as Indy remains out of focus throughout the shot. Figure 1.5 – The longest take in Raiders of the Lost Ark, slight reframes

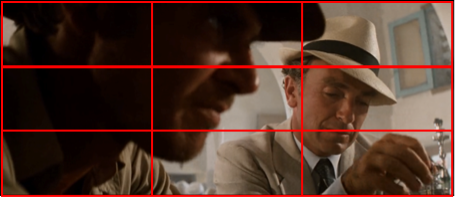

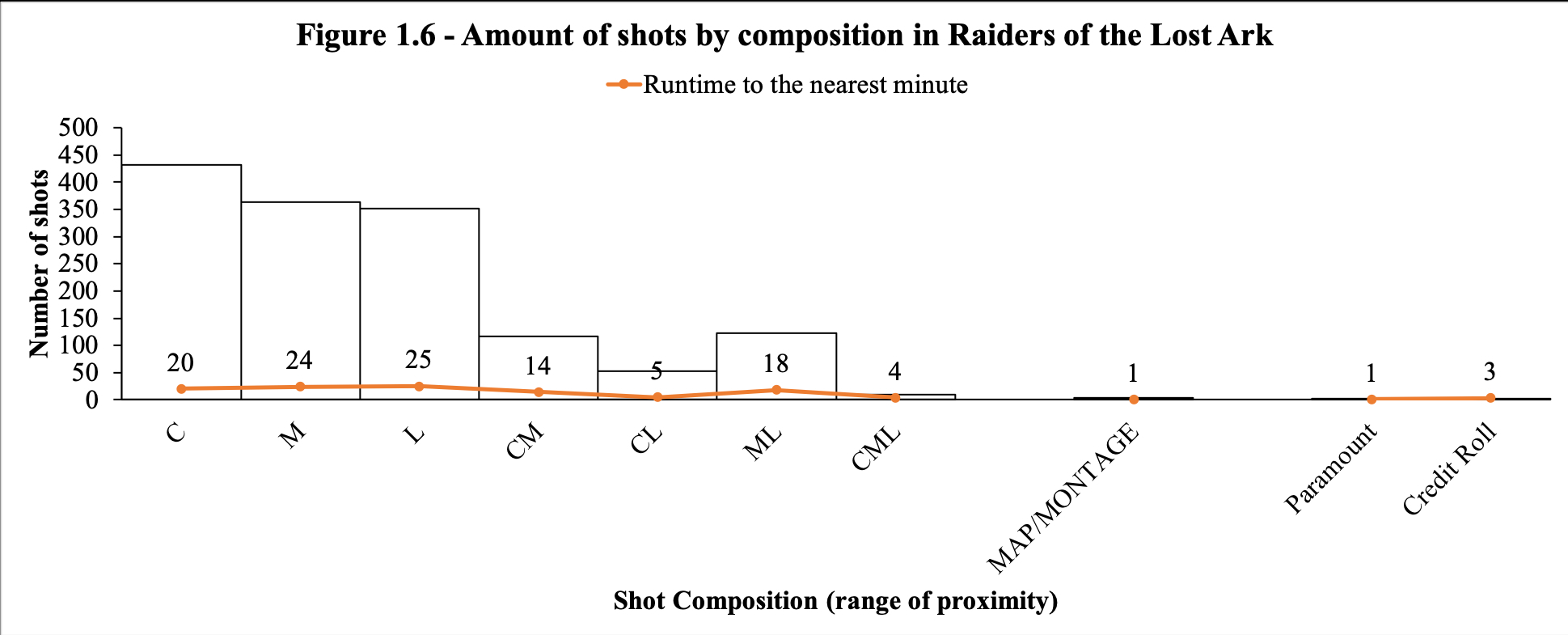

Shot Composition. In terms of framing, 432 (30%) out of the total 1454 shots are exclusively in the close range (between extreme and medium close-ups) while 364 (25%) are in the medium range alone (wider than a medium close-up but closer than a medium long shot), and 351 (twenty-four) in the long one (medium long to wide shots). This reveals a majority of 79% of the movie's cuts being to shots where characters (or objects in a setting) are framed moving or standing within one range of proximity. Cross-referencing with time on the screen, a sixty-nine minute majority is also found in adding up the twenty minutes a close range alone is on display, twenty-four of medium range, and twenty-five of long range.

Figure 1.6 details the comparison between the shot ranges and their screen time, which is helpful to identify the most common range across shots (whether covering it exclusively or simultaneously with others), not considering map montages and the bookend Paramount logos. In this sense, 610 shots overall (42%) feature a close-range framing of a character or detail in a setting, equaling forty-three minutes of screen time; 613 shots feature a medium range and total sixty minutes, and 535 shots contain a long range, totaling fifty-two minutes. This data reveals the medium range is present in over half of the 115-minute runtime, which suggests a similar reliance on the different ranges – nearly equal in the case of close and medium – when selecting shots for the edit. If the screen time of the combined range shots is added, this formula results in at least forty-one minutes (35%) of the movie relying on deep space dynamic. The simultaneity of close, medium, and long ranges is the most unusual, though, both in the number of shots used (nine) and screen time (four minutes), implying that there are usually no more than two centers of activity to attend (whether a human or non-human element is functioning as one). The data above reflects decisions of blocking, which are determined prior to the editing by the director and director of photography in conjunction with the performers' movements. However, this directing style is still relevant for the edit as it can be considered in analyzing decisions of choices to cut and not to cut, depending on what a shot is already covering. This fact prompts an examination of the characters being framed in a given shot. 536 shots focus on one character, which translates into 36% of the total number and is reflected as thirty minutes of screen time. 372 shots (25%) frame two characters, which is reflected in thirty-eight minutes. Thus, 60% of the runtime of the movie relies on either single or two-shots. Only 129 shots (8%) feature no characters, which amounts to seven minutes. Cuts per minute. While Raiders of the Lost Ark was cut in analogue format and not with equipment offering the different displays of temporal data as digital technology does, extracting a model of its assemblage for creative and critical consideration should assess any potential metric intents or trends. An approach to pacing is to calculate the number of cuts per minute. Ben Burtt, sound designer for Raiders and picture editor on the Star Wars prequel trilogy, has engaged in such computations, arguing the effect that digital visualization can have on editing:

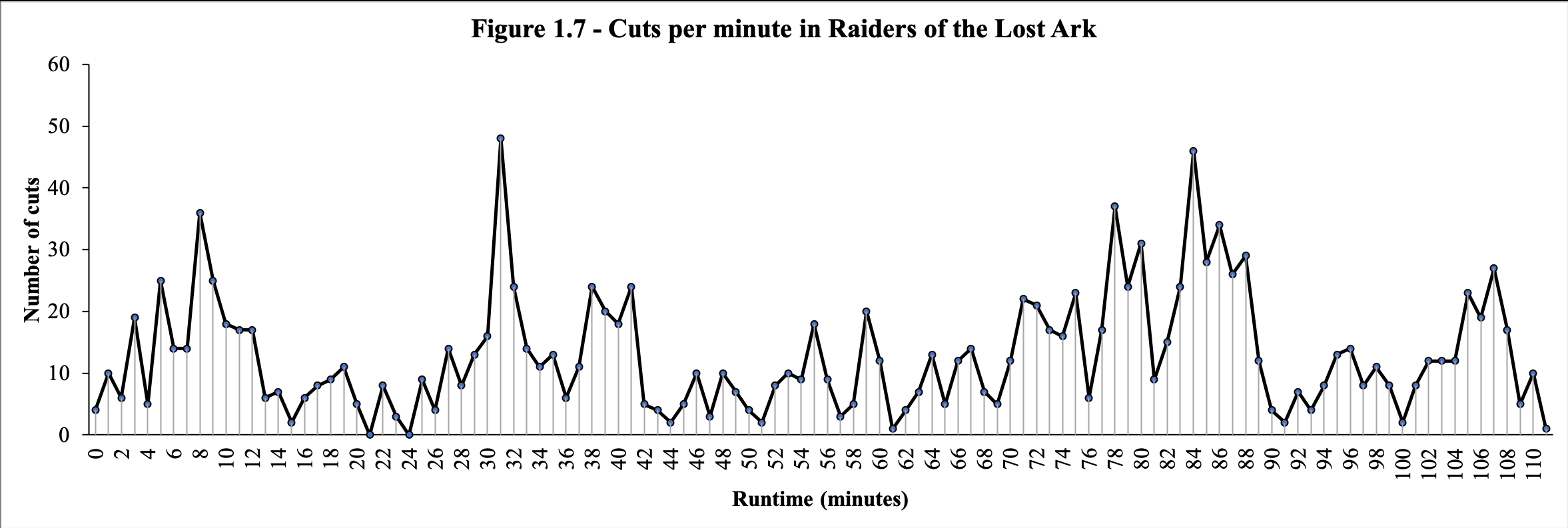

Considering 1452 as the total number of shots without the credit roll and the closing Paramount logo, the average shot count per minute (a comparable number to the number of cuts) would be 13.08, which lines up with the movie's average shot length of 4.6, as the product of the two values would equal roughly sixty (a full minute). Figure 1.7 shows the evolution of cuts per minute throughout the movie, without end credits.

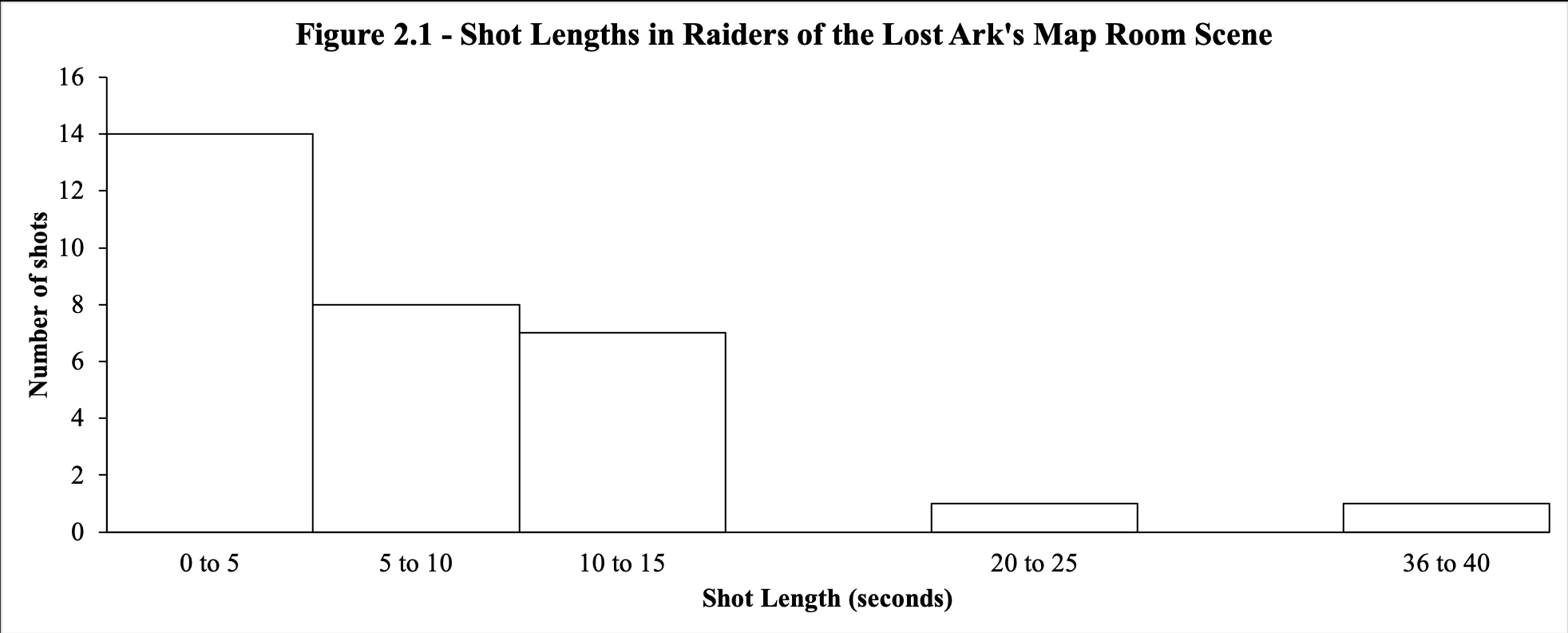

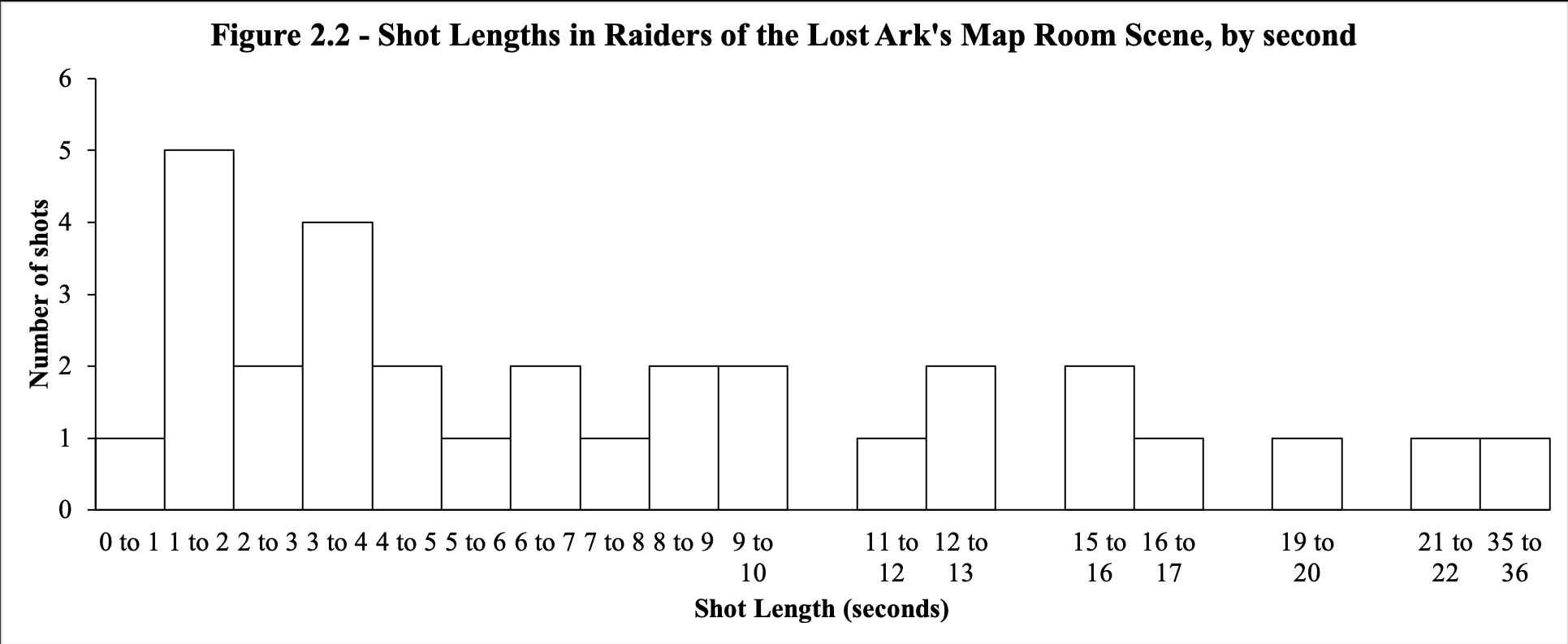

The graph identifies two peaks that seem to divide the runtime of the movie into three parts at minutes thirty and eighty-four. The first of these corresponds with the gunfight at The Raven tavern between Indiana and Marion Ravenwood, on the one hand, and Major Toht (Ronald Lacey) and his henchmen, on the other. The second is the truck chase between Indiana and the Nazis to seize possession of the Ark of the Covenant. While this action could be associated with structures for a standard feature, further analysis of the graph would need to account for scene or sequence breaks to better understand the behavior of this changing rate. The two lowest points indicate long takes over a minute long, so minutes with minor, but actual cuts are desirable for analysis. Analysis: Part 2: The Map Room SceneShot Length. The scene during which Indiana Jones sneaks into a map room of the old city of Tanis that was discovered in Cairo by excavators under the recruitment of the Nazis in order to locate the Well of Souls, comprises thirty-one shots that last approximately four minutes and eighteen seconds. No shots in the scene last more than a minute (the longest one spanning almost thirty-six seconds and twenty frames). Fourteen shots last between thirteen frames and less than five seconds, which takes a little more than half a minute of the totality of the scene, confirming the scene's reliance on takes that encompass the unfolding of actions within the same frame. Figures 2.1 and 2.2 illustrate the trend of shot lengths that coincide with the overall movie's most frequent duration of a shot being between one and two seconds (a couple of shots between two and three seconds in the scene only last one and five additional frames, respectively, after the two-second mark), but not taking up a large amount of screen time. .

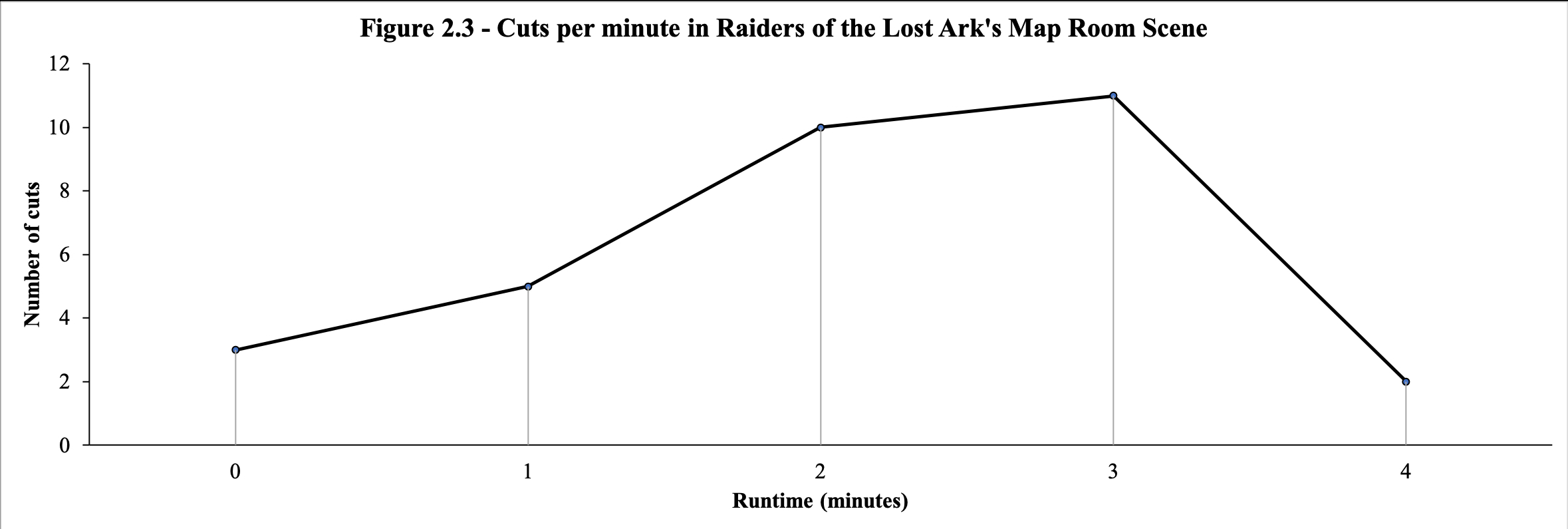

Calculating the average shot length of the scene by dividing its approximately four minutes and eighteen seconds in its thirty-one shots, the value obtained is 8.32. This is more or less double the value for the whole movie, which confirms its more paused action and pacing in this segment of the narrative. The number of cuts per minute (in this case, rounded to four minutes total) is likewise 7.75, which is only a little more than half of the movie's 13.08 mean value. Figure 2.3 displays the evolution of cuts per minute in this scene.

Isolating the map room scene from the rest of the movie allows for a clearer perspective and potential understanding of how the editing behaves and what it obeys. This analysis does not consider cuts belonging to other moments in the same minute after the scene starts and ends, which makes scenic patterns more accurate, though the unseparated measure is still relevant when analyzing larger, sequential trends and movie-wide evolutions. As the above graph shows, the number of cuts per minute in this case begins at a low count of three, rises to a level of five in the next minute, steepens to ten in the next one, reaches a plateau by only increasing to eleven during minute three, and finally drops to two cuts in the final minute. The scene's performance by number of cuts exhibits a gradual intensity building that accelerates, lasts, and plummets. Thus, it displays a kind of bump not dissimilar to the one that would be expected from action-filled scenes in movies such as the James Bond pictures, but in this particular extract, the slower-paced sections are as significant as the faster-paced ones, the former having from a fifth to half of the number of cuts from the latter.

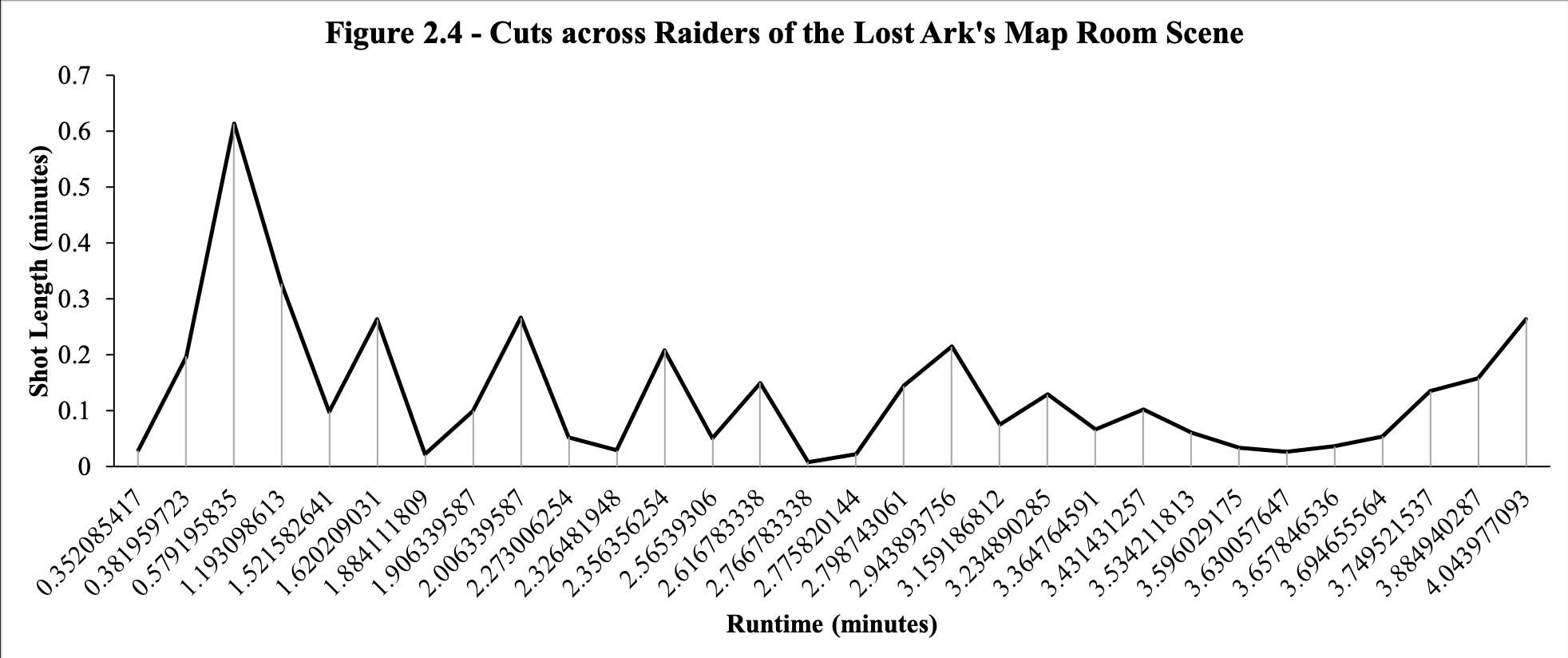

A map of the shot lengths across the scene, shown in Figure 2.4, shows a trend where longer-duration shots are sandwiched between one or two shorter-duration ones. Peak shot lengths are not maintained for two consecutive shots, while short-duration shots do so. Similar to the cuts per minute on Figure 2.3, a plateau is reached in the third quarter of minute three, with four shots of consistently similar short duration. The end of the scene likewise picks up in its use of longer duration shots, framing the pinnacle of those four minutes as the series of brief shots. Of significance from this graph is the fact that the longest-running shot, by far, is situated towards the beginning (the fourth shot, as presented in Figure 2.5's mosaic of the succession of shots in the scene). Serving as the establishing shot of the interior of the map room (the exterior was shown in previous shots), it follows Indiana Jones in a tilt down from a low angle to an eye-level framing as he descends into the cave by rope. The camera then pans from left to right as he walks across the room for the first time. The shot acts as a wide master that presents the space in a view past 180 degrees. Figure 2.5 – The Map Room Scene in Raiders of the Lost Ark, in screenshots

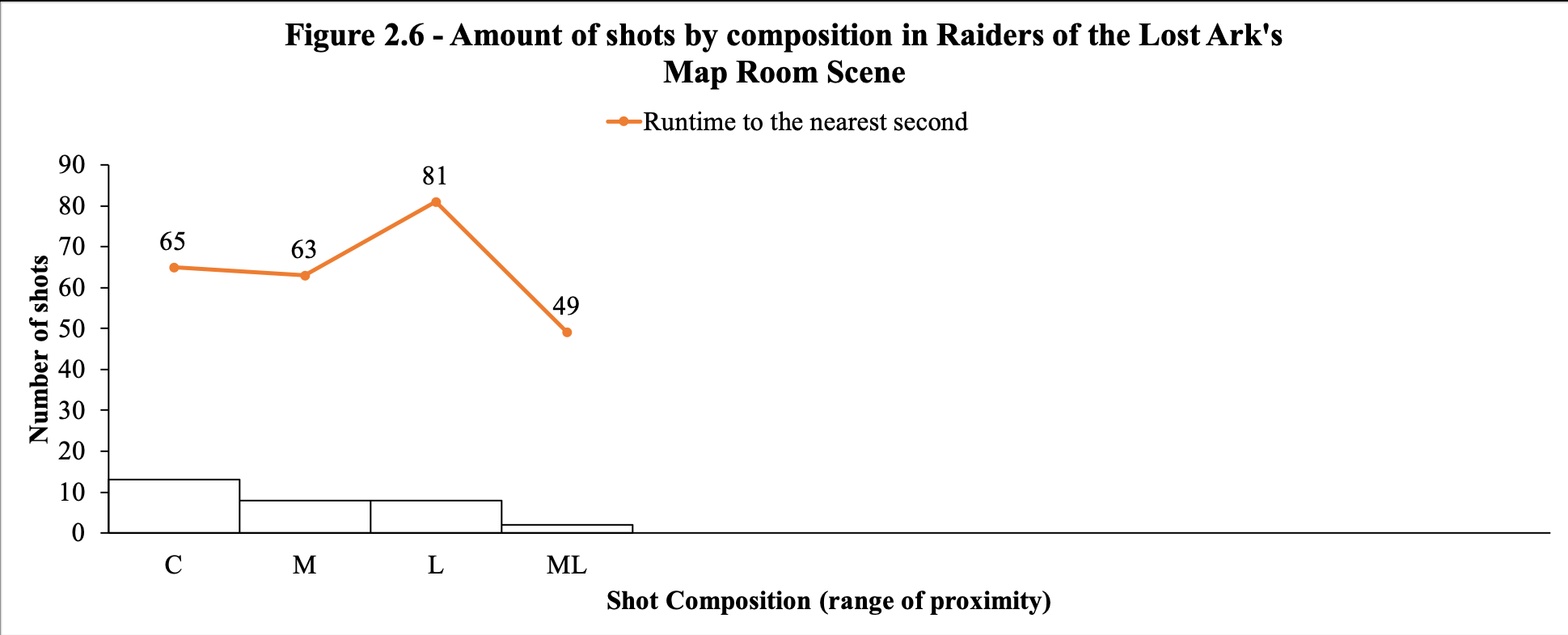

Camera Positions. In terms of the displacement of the cinematic perspective, out of these thirty-one shots in the scene, eighteen shots find the camera fixed on one position and amount to approximately 1.27 minutes. In contrast, eleven shots feature two or more distinct frames for a total of 2.74 minutes, which makes slight reframes a minority both in shot numbers and their time on the screen. When the shots with little to no camera movement are paired with such slight reframes, though, what results is that the majority of cuts in the scene are to a camera-static position (or an almost static one), but the majority of time on the screen requires camera movement. Fixation on a single frame for the legibility of the story world image is prioritized here (aided by the fact that a character is present in six of these shots, making the others inserts of objects or views of the setting). Almost a third of the shots in the scene (nine) feature no characters at all but are inserts (in close range) of the setting, amounting to only half a minute, so 10%. Even in scenes developing the story world, the visible presence of the character in its unfolding spatially and temporally is more important than the settings and objects, which are still significant to cover. Shot Composition. Regarding camera proximity, thirteen shots in the scene employ a close range (not substantial enough to conclude a clear inheritance from television aesthetics) while eight are of long range, eight are of medium range, and only two have both a long and medium range (both of which also contain more than one camera position). The fact that the latter two shots total only forty-nine seconds of the scene makes the overwhelming majority of shots in the scene not rely on the deep staging of movement otherwise associated with Spielberg's directorial style. However, comparing these numbers with time on the screen as shown in Figure 2.6 below, the most frequent proximity in the scene’s runtime is the long one, and most of the time is spent covering the scene in long and medium ranges as well as in a mixture of the two.

Shot Dynamics. Seven of the shots in the scene display a framing already used by a prior one, totaling sixty-eight seconds. These shots amount to more or less 25% of the total, which would suggest that the repetition of camera positions is not what the scene depends on to achieve a perception of stasis or settlement and thus, of a lower pacing, even though it may have some effect on it. What the scene does rely on is the use of similar and, therefore, familiar vistas to round up the geography of the room as framed, with the camera positioned always on one side of the 180-degree line. The scene also recurs to a master – main and reverse – on five occasions, two of which are brief but that confirm and prolong the action seen in closer shots – the sunlight passing through the staff head and pointing to the miniature map of Tanis. Once the scene follows Indiana descending into the map room, it is cross-cut on three occasions with shots of the exterior, where his friend Sallah (John Rhys-Davies), who was waiting for him, is briefly taken away by Nazis and must find his way back to the room entrance with a new rope to help Indy come out. This intercutting breaks the immersion of Indiana in the map room while allowing for his time inside to be tightened or elaborated. During each occasion the narrative cuts back to him, he performs a different action in the scene as indicated by his change of position. Sallah's moments also act as a force of antagonism to what is otherwise Indy's straightforward test of the method to uncover the location of the Well of Souls from the map. The cuts to Sallah come as Indiana advances one stage in his pursuit of knowledge – orienting himself in the map room, finding the spot to position his sundial-like staff, positioning it, and witnessing the location of the well revealed by sunlight. Sallah's actions also each play over a single shot, which contrasts with the more analytical montage of Indiana's. While displaying the antagonistic forces of time limits and spatial entrapment in Indy, Sallah's shots also act as a breather and tension release for the stasis and concentration of Indiana in the interior of the map room. These edits are gradually spaced out – first cutting in Indiana's footage almost forty seconds after they separate at the entrance of the map room, then after fifty seconds focusing on Indiana, and finally seventy seconds after last showing Indy. Functioning as a midpoint, the map room scene exemplifies an effort in the edit to balance the elements that make Raiders of the Lost Ark's rhythmic experience: faster cutting is opposed and placed in dialogue with slower cutting providing a spectacle that assists a diegetic progression and mapping. Thus, the main character is allowed to get up close to the world around him and contemplate it, and this process provides him – with knowledge from the world of the story – the seeds for actions to follow in the development of the narrative.

Conclusion: Miles AheadFrom its design, Raiders of the Lost Ark was constructed as a cinematic work dependent on an efficient succession of actions to portray its protagonist and goals in the plot. Michael Kahn's edit reflects this, but also acts to subtract from its quickness through slower sequences. The map room scene serves as an example, but Raiders is also a movie that refuses a uniform analysis in terms of the edit. Rather, and in possible analogy to its episodic nature as opposed to the classical three-act structure, it is more of a set of sequences, a succession of scenes, or a cross-cutting of simultaneous scenes, where each operates in relation to the others. Another potentially insightful endeavor would be to compare the movie with its 2023 legacy sequel, Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny. It is the only entry in the series not directed by Steven Spielberg and cut by Michael Kahn (nor with George Lucas's authority in writing, producing, and editing), but with James Mangold at the helm, and Michael McCusker, Andrew Buckland, and Dirk Westervelt performing the edit. This salient change in directorial and editorial criteria can allow for an understanding of how the cutting functions in Raiders, based on the moviemakers' statements that the original picture was their reference when it came to making a new one. How Raiders is channeled and how it is not in the latter release can better delimit its ever-resonant nature.

|

Journal Home

AmericanPopularCulture.com