|

Featured Guest With a Ph.D. from Yale University, J.E. Smyth serves as Professor of History at the University of Warwick in the UK. Her books include Reconstructing American Historical Cinema from Cimarron to Citizen Kane; Edna Ferber's Hollywood: American Fictions of Gender, Race, and History; Fred Zinneman and the Cinema of Resistance; and Nobody's Girl Friday: The Women Who Ran Hollywood. She has won the AAP Prose Award for Media and Cultural Studies as well as an International Association of Media and History prize. Four years ago, she was named an Academy Film Scholar by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

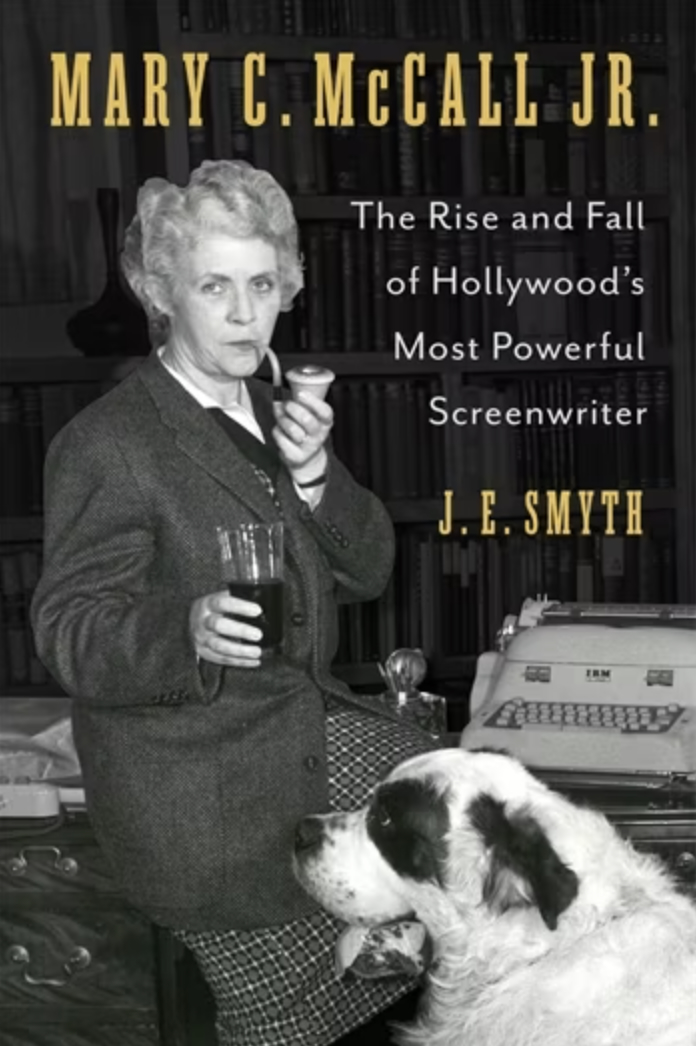

Tell us the story behind the choice of cover photo for your book. We often discuss this image in our film history classes. She seems to be having a bit of fun with patriarchal expectations, no? Perhaps a mischievous twinkle in her eye... It certainly catches the eye, doesn't it? The first time I saw the photograph, I knew if I ever finished the book and found a publisher, it had to be on the cover. It was taken to commemorate McCall's re-election as president of the Screen Writers Guild in 1951. It was her third term leading the guild, and many were relieved and even triumphant that she was back in power. Since McCall had stepped back from the top leadership at the end of World War II, things had gone from bad to worse for writers. The blacklist was spreading like wildfire, and right-wing Republicans used Hollywood to generate headlines to benefit their own careers. Writers were easy targets. Hollywood producers would step up occasionally to protect the reputation of a valued star, but they weren't interested in saving the jobs of mouthy intellectuals who had fought them for ten years to get decent pay. Many of McCall's colleagues lost more than their jobs during the blacklist. In 1950, her colleagues begged her to rescue the guild; there were more interrogations or "hearings" planned in California, and that fall, several screenwriters, including Carl Foreman, were targeted. And these hearings were televized. So, the Screen Writers Guild race in 1951 was contentious – the previous president was not popular. He'd cozied up to the right-wing conservatives, supposedly to take the heat off the Screen Writers Guild, but it left many people feeling angry and betrayed. Some worried he'd undermined the contract and that writers would soon lose their right to fair screen credit – something McCall had fought for since the beginning of her Hollywood career. After the election, there was a sense of hope – and also anticipation that McCall would not back down from a fight. The politicians, journalists, and even filmmakers targeting people on the left in Hollywood were not only anti-writer and anti-Roosevelt, they were also misogynists, racists, and xenophobes. Some pro-blacklist pundits referred to McCall as "a female of the species." They hated her feminism. So back in the president's office, with its floor-to-ceiling bookshelves, she did lean into this and clown around for the camera – borrowing a male friend's tweed blazer, brandishing an iconic Calabash pipe – made famous by stage and screen actors playing Sherlock Holmes, one hand around a pint of beer. That isn't a real dog sitting at her knee, sadly. McCall always had dogs at home, but I have it from a reliable source that this St. Bernard was stuffed – just a prop. But it added to the whole atmosphere of Victorian eccentricity, entitlement, and power – with a woman in charge! She posed and evoked an era when writers were outsized personalities – superstars of their age. And in taking a leaf out of the Sherlock Holmes myth with the pipe and the study, she was sending a very clear message in the photo: "I am back and I am going to solve your problems, Watson." Elementary.

As you mention, McCall served as president of the Screen Writers Guild during a crucial time — what were her biggest challenges, and how do you think her leadership shaped the future of the Guild? Did she have a single biggest achievement? I love America in the 1930s and the war years…the best of times and the worst of times. McCall did so much in her career – it's exhausting to list everything – but her biggest achievements were drafting the Screen Writers Guild's first contract, getting the government to back the Screen Writers Guild as the only Hollywood union for screenwriters, and negotiating the contract with Hollywood's producers. Those producers did not want to sign. They did not want to give young writers the same salary rates and protections as veteran writers, but she insisted. She got credit protection, and she negotiated pay raises during the war. She brought writers to the top table for a few years. These are historic achievements, unequalled by any other guild president. Writers mattered when she was in charge. It was an exciting time, but she wouldn't have achieved so much if she hadn't been able to compromise and to create a moderate coalition of industry allies across the political spectrum. After all, this was a woman whose best friend was a Republican, Charles Brackett. She also raised screenwriters' status within the industry as a whole because she reminded everyone that without a script, there was no film. In the 1930s, many writers refused to belong to the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences – that organization was controlled by the producers and was anti-union. One writer who was awarded an Oscar in the mid-1930s famously boycotted the awards. But once writers had the contract, McCall and her associates became players in industry governance. She even managed the production of war documentaries. She was on just about every industry committee in town. Later, as a founding member of the Academy Foundation, she envisioned an academy film school, an international film festival, and a major research library. She even wanted grants set aside for scholarly research on film history – so ironically, she was one of the people who laid the foundation for the grant I got to write her biography! But McCall cared more for other writers than her own ego, so I think she would have said what was most important to her was the work she did helping individual writers who were victims of credit theft, speculative writing, and chronic underpayment. She was also the one who pioneered close links with the Screen Actors Guild and the Motion Picture Editors Guild. She had a vision for the guilds uniting to manage and care for the industry, rather than the producers. It was so inspiring when SAG and the Writers Guild of America West got together to support each another during the recent strikes. It reminded me of the 1930s, when the guilds were so close.

Tell us more about women in the 1930s – McCall's generation of women in the workforce. There are a lot of misconceptions about American women in the 1930s. It's assumed they were shrinking violets, always deferring to men, masking their intelligence, preferring marriage to careers. Not for Hollywood's women at that time, and not for many other women in other industries. Women's employment was rising steadily – even in the Depression. The idea pushed by so many pop historians that women didn't become a presence in the U.S. workforce until the Second World War is nonsense. McCall's generation of women were university women – the numbers of women and men attending university were evenly split during the 1920s. For many women of McCall's generation, the Equal Rights Amendment wasn't a dream – it was within their grasp. They were confident and believed they could do exactly what men could do. They weren't under any illusions it would be easy. They worked twice as hard, sometimes for half the pay, but many women, including McCall, out-earned men in their professions. They were tough.

McCall was from a wealthy, Irish-American family. How did that play into her career? Yes, McCall wasn't just well educated and articulate – she was also from one of the wealthiest families in New York. This gave her some hard-nosed confidence and attitude, and it also meant that she knew how Hollywood's rich men thought. She knew what made them tick and how to manipulate them. This came in handy when she was the only woman in the room negotiating the writers' contract. Producers may have thought she was "one of them" – or at least, that since she was from the world of business and money, she could be persuaded to "play the game." But she was a union woman through and through and a Roosevelt Democrat for life. No one intimidated her. She also leveraged her Irish American background. There was a strong Irish American "family" in Hollywood – most of them old New Yorkers. They banded together, met socially, and watched each other's professional backs. It wasn't only men like James Cagney – McCall was also a player. Eddie Mannix, MGM's tough guy executive, was also Irish American and they got to know each other by serving on the same charity committees. Irish Americans back then were fully signed-up to community service, charitable giving, and Hollywood was not just a film industry, it was also a network of social relationships. Mannix liked her – she was blood, so to speak. Their friendship paid off because when he was sitting at the executive table during union negotiations, he ended up persuading his Jewish mogul colleagues to listen to what she and other writers had to say. Darryl F. Zanuck liked her hustle and fight mindset – these are Irish stereotypes, for sure, but she used them to her advantage around powerful men. Of course, it also helped she was a good-looking woman in Hollywood. She had affairs, but they were personal things that didn't interfere with guild business or work. She was a bridge builder, a compromiser when it helped the most writers – men and women.

Discuss McCall as writer. McCall had a reputation for being able to write, adapt, or polish anything at the studio. She started out writing fiction in mainstream glossy magazines – sometimes aimed at women, but not always. She wrote about men too. At Warner Brothers, she was one of two women in the writing department, but producer Hal Wallis assigned her to gangster films, musicals, historical romps, Shakespeare, adaptations of contemporary novels written by men – she was not typecast as a writer of "women's films." When Wallis was in trouble because other male screenwriters had screwed up a project, he turned to her to fix it. She could turn a script around in twenty-four hours. So she was earning a good salary at Warner Brothers, but it was only at Columbia and later MGM and Twentieth Century-Fox where she made the big bucks. After 1936, she made films with other women creatives, wrote a female-centered franchise, and even made a hit war film. The point is, when she didn't have the choice of assignments, producers gave her stories that might have appealed more to men, but when she could call the shots, she very often focused on women's stories. She also went out of her way to write about how she succeeded in Hollywood, to advise younger writers who wanted percentage deals.

Given McCall’s work is often overlooked or forgotten – hence the need for your book – what do you think her story reveals about the larger problem of erasure of women in film history? Since the 1960s and the fall of the old studio system, a set of myths has taken hold about Hollywood's past – that the film industry was totally male and that women could either be sexualized actresses, passive objects of the camera, or anonymous secretaries. Many historians of the silent era have struggled to correct these errors – women in early Hollywood were particularly powerful and there were a number of women directing and producing. But even these historians still cling to the belief that women lost all power in the industry after it really started to make money in the 1920s, and that by the 1930s it was a man's game. They have even argued that women and labor unions didn't mix in Hollywood. Ironic indeed when you consider McCall's career, or the journalistic coverage by reporters like Bob Thomas and Hedda Hopper in the 1940s, who hyped women's diverse careers and even stated that women made up half of all film workers in the studio era. When I was studying film at graduate school, we learned nothing about women in Hollywood. It was all about men – male director-auteurs who called all the shots. I spent a lot of graduate school being pissed off. Well, you know as well as I do that since the 1960s, film studies has thrived on the notion of male directors being the most important artistic factor in a film's production and meaning and that historically, this means that screenwriting, film editing, costume design, research, legal, and publicity, where women did have prominent roles, were hardly ever discussed. Once you admit film is a collaborative art and business, you have to see the women – and when film studies became "serious" academic territory or a pop philosophy for film mavens following the likes of Andrew Sarris and Richard Schickel, serious was a "male" thing. Women just got cut out of the history books being written about the industry in largely the same way they were absent from classic movie criticism. Film archives, which really ramped up acquisitions from the 1960s, similarly ignored women. They wanted male directors' papers, not McCall's. Unfortunately, many prominent Hollywood women threw away their papers in the second half of the twentieth century, so our knowledge about their careers is lost forever – another casualty of this algorithm of misogyny.

You've done a lot of interviews discussing this book. Is there a question nobody ever asks you about her that you wish you had a chance to talk about? There is – thank you for asking! No one has ever asked me if McCall regretted leaving her life as a writer in New York for a career as a screenwriter and labor leader in Hollywood. Maybe that sounds shocking coming from someone who's supposed to be a film historian. I think most people are like: "Hold on – Hollywood equals fame and big money, so why would she regret it?" It's true she became one of the most highly paid writers in Hollywood. But McCall was a real writer. She had the potential to become a great writer of fiction in her twenties. She also knew people in New York theater and could have turned her hand to the stage, where she wouldn't have had gangs of assistant producers and yes-men telling her to change her script. She started out as a courageous, risk-taking freelance, the breadwinner in her home, and she thrived on independence and that rush of the unknown that faces every writer who needs to pay the rent at the end of the month. McCall knew that when she was under contract to the studios, she was basically ceding her creative independence – everything she wrote became the property of the studio she worked for. As a guild leader, she also recognized that in making the writers' contract legally binding, she was giving screenwriters a financial safety net, but each guild member individually ran the risk of becoming too safe, well-fed, and under the coercive thumb of less intelligent, crass businessmen who wanted to exploit the public by forcing writers to adapt the work of others. A paycheck was nice, but what about the work she was doing? It's a question all writers in Hollywood still face: Is it worth all the creative interference and bullshit you have to put up with day after day? And now there is AI stealing everything in sight. When McCall was out of the industry and really poor in the late 1950s, she went back to freelance writing and produced a great short story, "The Friday Girl," but she was so worn out by fighting for the guild, fighting the blacklist, the misogyny, an abusive husband, that she just ran out of the energy a writer needs to produce those new ideas. Life – or Hollywood in her case – had run her into the ground. In 1952, McCall sacrificed her status in Hollywood by helping a communist writer who'd been stripped of his screen credit. When she dared to sue a producer, the establishment went after the guild and her, determined to break both. So did she regret her career choices? I might be sad about it and think "what if?", but McCall was unbreakable. She owned her successes and her failures and fought on. She was a true visionary, and believed in Hollywood's possibilities as a thriving, creative community with respect for all writers. I wish there were more people like her, but she was a true original without a sequel.

Leslie Kreiner Wilson, Interviewer and Editor https://americanpopularculture.com/journal/articles/spring_2025/smyth.htm

|

AmericanPopularCulture.com