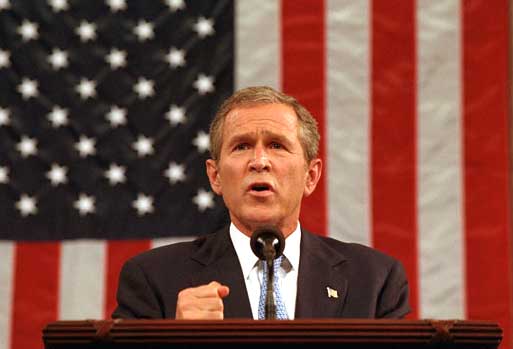

In an address to the nation, on March 17, 2003, George W. Bush declared, “Saddam Hussein and his sons must leave Iraq within 48 hours. Their refusal to do so will result in military conflict, commenced at a time of our choosing.” The ultimatum aroused a multitude of commentary in editorials and news articles that depicted George W. Bush as a cowboy sheriff who told outlaws to get out of town or face the consequences. On March 19, for instance, Reuters ran a story titled “High Noon for Cowboy Era” in which the lead sentence declared that, for Arabs, Bush's ultimatum was a throwback to the Wild West. The commentary prompted by the forty-eight hours ultimatum was not the first time Bush's actions had been referred to as cowboy-esque. After September 11, 2001, as editorial writers and public figures discussed terrorism more vigorously, they frequently described Bush in terms of a variety of cowboy images that went well beyond the cowhand who works cattle and drives them to market miles away. In the months leading up to the war with Iraq, commentators began to portray Bush as a sheriff in the Old West who would go it alone without a posse if need be in order to defeat what he saw as lawlessness and evil. Europeans, who would not join the posse to defeat the outlaw, were compared to timid saloonkeepers and shopkeepers, afraid to confront evil and afraid of the sheriff who might shoot up the town while getting his man. Eventually, the sheriff realized he had to ride out without a big posse. Tony Blair became Tonto to Bush's Lone Ranger and rode along to cover his boss's back.

As the image of the cowboy dominated debates over the war with Iraq, it became obvious that the term “cowboy” was lodged securely in the national and international consciousness as a means of delineating positions. I examined editorials and news articles published in newspapers and magazines both in print and on the Internet, beginning September 11, 2001, and continuing through April 2003 in order to explore the ubiquitous representations of George W. Bush as a cowboy. I read these editorials and news articles to answer one primary question: How and why has the myth of the cowboy been used in shaping public opinion about the war with Iraq ? Answering the question was a challenge because I immediately confronted the slipperiness of the signifier “cowboy” and the generative quality of the story of the American cowboy, now widely called the cowboy myth. As I will discuss in more detail below, numerous writers have traced the evolution of the myth from the original era of the trail-riding cowboy in the late 1800s through contemporary images that are a mixture of the historical and the fictional. In understanding the news commentary, then, I was first caught up in the structuralist endeavor of investigating the myth as a pattern for understanding a certain type of persona. I then recognized that the cowboy myth appeared in so many editorials and news articles, building and growing from writer to writer, that it formed a multi-faceted story.

I also wondered why the cowboy myth was still being used in political rhetoric early in the twenty-first century. In 1955, Franz and Choate asked the following question in their work, The American Cowboy: The Myth and the Reality : “Why this everlasting preoccupation with the cowboy in a country that is supposed to be crassly treadmilling its way to an ever increasing urbanization and ulcerated pursuit of happiness through money?” The question seemed even more puzzling in the context of urbanization and consumerism that have proliferated beyond what most individuals in the mid-1950s could have imagined. Most editorialists and politicians who exploited the cowboy myth most likely lived in urban areas and were far removed from the austerities of life on the cattle trail and the frontier. Obviously, the myth of the cowboy persists not because many people live like cowboys but because it defines something significant about the character of the U.S broadly and the character of George W. Bush specifically. What the cowboy myth means, however, is complicated because, as Frantz and Choate have explained, the cowboy represents both a desire for violence and recklessness and also the pursuit of heroism and integrity. Furthermore, as recent theorists have also explained, the line between the good and the bad cowboy is ambiguous because some people view the cowboy's will to act, even violently, as an honorable trait while others are repelled by the aggressive, eager-to-shoot image. Given the blurry line between the bad cowboy and the good cowboy, I was surprised that editorialists and politicians had adopted the cowboy myth in conveying their views of an international conflict.

I will argue that in spite of the slipperiness of the term cowboy, the complex evolution of the cowboy myth, the anachronistic aspects of the historical cowboy, and the blurry line between the good and bad cowboy, both those who supported and those who opposed the war with Iraq used the cowboy myth successfully to influence public opinion. Many columnists and public figures outside and within the U.S. used the cowboy myth to create a very negative image of George W. Bush as a blood-thirsty, trigger-happy loner. The love of the cowboy in the U.S., however, became a potent means of coalescing support for George W. Bush as a fast-acting, straight-shooting, brave president. The cowboy myth produced positive associations for segments of the U.S. public that held conservative views while the myth produced negative associations for segments of the public with more liberal views. As I will explain, this dichotomy aligned with a view of the frontier promoted by Frederick Jackson Turner and the opposing view promoted by New Western Historians and those who have called for the abandonment of the cowboy myth. My reading of editorials that analyze the presence of the myth in the discussions about the war with Iraq (the meta-commentary) leads me to believe that Bush's image as a cowboy president was more positive than negative in the U.S.; in Europe, however, a negative image of the cowboy reinforced a disgust with Bush's handling of the war with Iraq.

PATTERNS OF THE COWBOY MYTH

In his essay “The Structural Study of Myth,” Claude Levi-Strauss clarifies how myths become timeless and operational: “On the one hand, a myth always refers to events alleged to have taken place long ago. But what gives the myth an operational value is that the specific pattern described is timeless; it explains the present and the past as well as the future.” He also tells us to analyze myths by breaking down their patterns into constituent units. His detailed process is clearly beyond the scope of this essay; however, he provides a good starting point for briefly thinking about the timeless quality and the specific patterns of the cowboy myth that operate in defining contemporary political positions.

As many writers have explained, the patterns that define the cowboy myth have little to do with the historical cowboy of the open range in the American West. Paul H. Carlson's designation of the classical era of the cowboy is helpful in understanding the genesis of the term “cowboy” and its contemporary applications. Carlson considers 1865-1890 the classical period, a time when cowhands, with an average age of twenty-four, road the open range. As he explains, many early cowboys were overworked, illiterate, inexperienced laborers who wore ill-fitting clothes and developed outlaw reputations. At least a third were Hispanic or African American, and some scholars claim many were Indian and Chinese. By the late 1880s, however, with the demise of the open range, more settled cattlemen took over the wilder business of the cowboy. With the end of the classical cowboy came fictionalized versions, changing the cowboy image. Buffalo Bill Cody's Wild West Exhibition in 1883 marked the beginning of a new image of the cowboy as “young, white, and virile.” Prentis Ingraham's novel, Buck Taylor, King of the Cowboys , Charlie Russel's paintings of cowboys, and Owen Wister's novel The Virginian also transformed the image of the cowboy from the illiterate, overworked cowhand to an idealized hero. Frantz and Choate claim the cowboy came to embody the qualities of a number of folk heroes: Daniel Boone, Indian fighter, buffalo hunter, gold washer, and mountain man. None of these images, however, persisted through time like that of the cowboy - which soon merged with that of the sheriff of the Old West, the gunslinger, and the frontiersman. “Reel cowboys” in movie and television productions have expanded the cowboy myth through characters such as Wyatt Earp and The Lone Ranger and through actors such as John Wayne, Gary Cooper, and Clint Eastwood. The rodeo cowboy, the urban cowboy, and the cowboy depicted in country western music have also expanded the cowboy myth by combining aspects of historical and fictional cowboys.

One important and timeless pattern in the construction of the historical and the mythical cowboy is the contrast between the heroic good cowboy and the rogue, bad-man cowboy. Frantz and Choate describe the idealized cowboy tradition: The good cowboy is brave and up for a challenge. He promotes justice and defends the honor of women; he is “the implacable foe of the Indian; and a man to whom honor and integrity come naturally.” As I will illustrate, George W. Bush and many editorialist have adopted the myth of the idealized cowboy in promoting the war with Iraq, while Bush's opponents have adopted the tradition of the rogue cowboy in promoting their opposition to the war. The bad cowboy is associated with such notables as Wild Bill Hickock and Billy the Kid. As a reckless ruffian, the bad cowboy is a pistol-shooting, merciless, hard-living man who roamed the boom towns of the Old West.

Some scholars have critiqued the cowboy myth and called for abandoning it because the good and the bad cowboy become intermingled; they argue that the violent aspects of the bad cowboy are idealized as embodying the essence of the American character. Richard Slotkin, for one, in Regeneration Through Violence (1973) and Gunfighter Nation (1992), explains how the myth of the frontiersman and the cowboy have sanctioned local and national violence; he argues the U.S. needs to cast off the cowboy myth because of its advocacy of violence and because it idealizes “the white male adventurer as the hero of national history.” Slotkin believes the U.S. needs a new myth that represents the changing demographics of the nation and that “does not reduce the parties of the American cultural conversation to simple sets of paired antagonists.” Sharmon Russell also calls for the abandonment of the cowboy myth and even goes so far as to urge us to “kill the cowboy” in his book title. While primarily arguing in favor of new ways of preserving the ecology of the Western States, he also asserts, “We need new myths and new role models, one that includes heroines as well as heroes, urbanites as well as country folk, ecologists as well as individualists.” Nevertheless, judging by the ubiquitous use of the cowboy myth in the commentary leading up to the war with Iraq, the cowboy myth has not been abandoned in favor of a new myth. Perhaps this results in part from the ongoing disagreements about the meaning of the West and the frontier in the development of the American experience.

In his 1893 essay, “The Significance of the American Frontier in American History,” Frederick Jackson Turner announced that the American West and the frontier developed the freedom-loving democratic character of the United States. Turner claimed the American frontier was closed by 1890, and, up until that time, the westward movement was central in American history and in the American experience. He claimed, “This perennial rebirth, this fluidity of American life, this expansion westward with its new opportunities, its continuous touch with the simplicity of primitive society, furnish the forces dominating the American character.” The frontiersman, according to Turner, defined what it meant to be an American as he moved west and left European influence behind. Most importantly, frontier life developed the individualism that promoted democracy, and it created a buoyant American character that thrived on freedom, strength, inquisitiveness, invention, and expansion.

John Mack Faragher contends that “Turner's essay is the single most influential piece of writing in the history of American history,” and in Rereading Frederick Jackson Turner , he traces the emergence of other histories of the west, including Richard Slotkin's, that contest Turner's glorification of the American frontier. One “New Western Historian,” Patricia Nelson Limerick, redefines the West as a site of “invasion, conquest, colonization, exploitation, development, [and] expansion of the world market.” In her focus on the West, Limerick includes “women as well as men, Indians, Europeans, Latin Americans, Asians, Afro-Americans.” She rejects Turner's idea of the closing of the frontier in 1890, and she contests the belief that westward expansion primarily meant progress and improvement. She, like many other New Western historians, points to the injuries to the environment and to individuals that resulted from the expansion into the West.

In the editorial clashes, Turner's glorification of the frontier conflicts head on with New Western condemnations of the violence and exploitation in the American West. The two conflicting versions of the West and the two conflicting images of the cowboy help explain why the cowboy myth has been used both to condemn the war with Iraq and to call the U.S. to war. The image of the cowboy gunfighter with a frontiersman mentality is offensive to those who resist the war with Iraq and who call for settling international conflict without violence and exploitation. At the same time, the image of the cowboy gunfighter is positive to those who support the war with Iraq and call on the U.S. to uphold the frontier ideal of bravery and integrity in the face of danger.

THE BAD COWBOY

Politicians and columnists outside the U.S. almost unanimously use the bad man tradition of the cowboy myth to generate negative associations about George W. Bush's policies after 9/11. For many columnists in non-European countries, the term “cowboy” was a means of condemning a bullying, ruthless U.S. military apparatus led by a cowboy-style leader. Praful Bidwai, for instance, writing in the Daily Star in Bangladesh about the U.S. policy on Afghanistan and Iraq in March of 2002, declared the cowboy style of U.S. militarism “unbecoming of a civilized state.” Bidwai believed India should protest the cowboy-style militarism instead of groveling before it, and he used the term “cowboy” to represent not just Bush but the entire U. S. military operation. Fahd Diab, editorialist for Al-Thawra in Syria, claimed Bush wanted “America to have the final word in every conflict as if it were the era of the strong conservative President Reagan, who led the world by his cowboy stick.” Regardless of the mixed metaphor, the word “cowboy” seemed to signify for Diab the presence of a bully on the international scene. After Blair produced a dossier on Iraq that claimed it had the capacity to use chemical and biological weapons, Wamid Nadmi, an Iraqi university professor educated in Britain, spoke to the BBC and warned England not to ally itself with “American cowboy policies” that had the goal of destroying Iraq. I might have expected an Iraqi professor to condemn U.S. policies using the cowboy myth, but I was surprised to see that Kuwaitis used the myth in a similar way. A Reuters news story by Michael Georgy stated that Kuwaiti citizens did not trust the U.S. and were tired of Bush's “cowboy style of leadership.” Obviously, lone editorialists and journalists do not speak for entire nations, but, taken collectively, a pattern emerges in the foreign media: Bush is a bullying cowboy-style leader of a ruthless U.S. military.

As the deliberations over a potential war with Iraq intensified, columnists in Europe also adopted the cowboy as bad man in clarifying their opposition to U.S. policy. In May of 2002 when George W. Bush traveled to Germany to build European support for a war on Iraq, Cameron Brown reported on NBC Nightly News that even the “German media are portraying Bush as a Rambo-like cowboy intent on going after Saddam Hussein with or without Europe's support.” David E. Sanger analyzed the European reaction to Bush's political style and declared that Europeans did not like Bush's tendency to paint political issues as “black-and-white certainties.” They didn't like Bush's religiosity, his “provocative manner, the jabbing of his finger at you.” The Texas culture was unfamiliar to the Germans, Sanger claimed, and Bush reminded the Europeans of what they disliked about Reagan. CNN's Walter Rodgers summed up the perceptions of Bush by the Europeans, claiming Bush's cowboy image “doesn't play well” in Europe. He quoted Piers Morgan editor of London's Daily Mirror : “I think people look at him [Bush] and think John Wayne. We in Europe like John Wayne, we liked him in cowboy films. We don't like him running the world.” Europeans, who are somewhat attuned to U.S. movies and culture, seemed to view the American cowboy through the lens of movies about Rambo and John Wayne and through images of Ronald Reagan and his cowboy persona. The result was an image of the cowboy with an assortment of cultural nuances, most of them removed from the cowboy who rides the range herding cattle; the cowboy image for Europeans seemed to center around a dominating man of action who always got his way.

Many columnists and reporters in the U.S. also used the bad man tradition in describing George W. Bush and seemed to relish extending and clarifying the negative connotations of the cowboy. After Bush spoke to the United Nations General Assembly in September 2002 to present his case on attacking Iraq, columnist William Saletan wrote in Slate that, prior to the speech, Saddam Hussein was widely considered a reckless troublemaker who required the attention of the international community. After the speech, according to Saletan, diplomats realized that now “another cowboy is riding into town, less crazy but with much bigger guns: the president of the United States.” For Saletan, the cowboy was the individual who rode into a town ready to shoot, and this image of the cowboy with big guns was extended in other editorials: Bush became a tough talking Clint Eastwood type with such a huge ego that he could not back down once he gave his word. John Ed Pearce writing for the Herald-Leader in Kentucky asserted Bush did not carry through on his promises regarding Afghanistan and eliminating terrorists. He says Bush, however, continued to be “riding high with his cowboy motif. He has a big white cowboy hat and a ranch. He talks tough like Clint Eastwood. He has the mightiest military machine, and it looks like he is going to use it. If he doesn't, the tyrants of Central and Southeast Asia will make fun of him. Can't have that.” Les Payne, writing for Newsday.com, extended the image of the cowboy riding into town with big guns in his critique of President Bush whom he claimed acted like a Texas Ranger, “one of the cold-blooded, bloodthirsty Texas lawmen” who are eager to dispense justice. Payne called attention to Bush's tendency for beaded eyes and finger pointing, which he claimed impeded U.S. diplomacy. Bush would attack Iraq, Payne claimed, in order to show that he was not “all hat and no cattle.” In summary, editorialists in the U.S. portrayed Bush, the cowboy riding into town, as a crazed, egoistic Texas Ranger, eager to shoot in the name of justice.

As the cowboy myth was widely used in the U.S. press as a weapon for ridiculing Bush and his policy on Iraq, Vice President Al Gore joined in the process, condemning Bush's policies on Iraq and making use of the bad man tradition of the cowboy to reinforce his point. Speaking before a crowd of five hundred people in California, Gore claimed Bush should focus on the war on terror first before engaging with Iraq and should garner international cooperation in any action against Iraq. After the speech, Gore told reporters that the Bush Administration had adopted a “do-it-alone, cowboy-type reaction to foreign affairs,” and that “there's ample basis for taking off after Saddam, but before you ride out after Jesse James, you ought to put the posse together.”

THE GOOD COWBOY

The posse aspect of the cowboy myth was off and running after Gore's comments, and the lone cowboy riding out without a posse is a particularly damaging image when one considers the cowboy also has been portrayed as an evil guy out for revenge and eager to shoot in the name of justice. With such an image in the public consciousness, the adoption of a cowboy persona by George W. Bush amazed me. After the injurious connotations associated with Bush's “cowboy diplomacy” abroad and in the U.S., Bush continued to play directly into the cowboy president image. Was this a calculated risk taken by Bush and his image consultants?

The lack of ambiguity in Bush's references to cowboy images, I believe, indicates that Bush purposely adopted the heroic, idealized version of the cowboy in defining his presidency. Even before September 11, Bush was cultivating a cowboy image of himself. In August of 2001, he provided photo opportunities to the press during his vacation at his Texas ranch. As several news articles commented, he road around dusty roads in his white Ford pickup with Rumsfield at his side “riding shotgun.” After 9/11, Bush clarified his desire to kill or capture Osama bin Laden by stating, “There's an old poster out West that I recall that said ‘wanted, dead or alive'.” In making such a statement, Bush was obviously not shying away from the image of the cowboy sheriff who dispenses justice, and he continued to reinforce his cowboy persona. At a National Cattlemen's Beef Association meeting in February 2002, Bush told the crowd, “Either you're with us, or you're against us.” After the Senate approved the War Powers Resolution in October of 2002, Bush thanked members of Congress and said, “The days of Iraq acting as an outlaw state are coming to an end.” The statements to the cattlemen's association and to Congress were somewhat veiled allusions to the cowboy, but by late 2002, Bush clearly embraced the cowboy myth.

In November 2002 at the NATO summit in Prague Castle, where Bush was generating international support for a war with Iraq, he said, “Contrary to my image as a Texan with two guns at my side, I'm more comfortable with a posse.” The timing of this statement is particularly interesting since Al Gore made his statements about Bush's willingness to ride out without a posse in late September 2002. Just before the war with Iraq began, Bush solidified his cowboy image by declaring that Saddam and his sons had forty-eight hours to leave Iraq. As the OTC Journal emphasizes, “This statement did nothing to mitigate Bush's cowboy image on the International political scene as it sounded like Wyatt Earp telling the bad guy he had 48 hours to get out of Dodge.” As the war with Iraq became imminent, the president, indeed, appeared ready to ride out to dispense justice without a posse.

TONY BLAIR AS COWBOY

Bush was not without one steadfast companion in the lead-up to war with Iraq, and because Tony Blair solidly aligned himself with Bush's stance on Iraq, he was identified as a cowboy also. Whether or not Blair's intent was as obvious as Bush's is not clear, and whether or not Blair was a good or a bad cowboy in the British press is also not obvious. It is clear, though, that the press relished using the image of the cowboy in illustrating Blair's support of Bush's position on Iraq. The British press, for instance, published photos of Blair with what was described as a “thumbs in belt” pose before a news conference on Iraq. The Daily Telegraph asked if Blair was “spending too much time down on the ranch with Dubya” and whether he was becoming a “faithful deputy, the meanest gunslinger in Durham County, strolling into the Sedgefield corral.” The Mirror , a popular London tabloid, printed a photo of Blair with the headline “Unforgiven” (the title of a Clint Eastwood movie) and called Blair's involvement with Bush a “two-hour epic starring Tony Blair: a man with a mission: To follow America's cowboy trail to war.” Blair's thumbs-in-the-belt stance was not lost on the international press. The BBC News reported that The Gulf Today , located in Dubai, analyzed Blair's posturing, claiming, “When Britons saw him with thumbs tucked into his belt cowboy-style ahead of his news conference on Iraq, his political stance on the Iraq issue crumbled. . . . A body-language expert even suggested that Blair is subconsciously mimicking Bush.” One political cartoon even showed Blair as Tonto, the companion to Bush as Lone Ranger. The portrayal of Blair as a cowboy in the British press adds an intriguing twist to the image of the cowboy as it was used in editorials; Bush became the Lone Ranger with Tony Blair as his loyal companion, and he also became a sheriff with a faithful deputy, also played by Tony Blair.

META-COMMENTARY ON THE COWBOY MYTH

As editorial writers began to recognize the ubiquity of the cowboy myth in commentary on the war with Iraq, some began to analyze Bush's cowboy image and tried to sort out the references to the good and the bad cowboy. Two editorials, for instance, analyzed how Bush fit or should fit Gary Cooper's image of the cowboy in the movie High Noon. An article in The All-American Post published by the Vietnam Veterans and Airborne Press asserts that George W. Bush should “examine his cowboy image” and try to be more like Gary Cooper than Clint Eastwood in Unforgiven who issues cruel threats as he leaves town. The article claimed Bush resembled the Gary Cooper style cowboy after 9-11 in his deliberate approach and gained much political capital; however, in his dealings with Iraq, Bush emulated Eastwood in Unforgiven . Brant Ayers, publisher of the Anniston Star , claimed the Bush administration had “blurred the quiet cowboy as a self-defining allegory” by being more like “a bad-humored, 20-foot American cowboy [who] tells the whole saloon he's going to drill the 3-foot bad guy, who doesn't stand a chance.” Ayers analyzed the Gary Cooper style cowboy and explained that Americans have looked up to the image of the quiet cowboy, personified by Gary Cooper as Sheriff Kane in High Noon , who only lost his quiet demeanor and fought when he was provoked by an outlaw.

As a result of my reading of other pieces of meta-commentary, I believe that the image of Bush as a heroic cowboy president had more currency in the U.S. than the images of him as an outlaw bad-man cowboy. Several elements appeared to reinforce the positive image of the cowboy president: the increasing popularity of Ronald Reagan who played into the image of the cowboy president during the dismantling of the Soviet Union; the American love of the cowboy - the impetus that generated so many westerns in the first place; and the ability to use the image of the cowboy to clearly distinguish a U.S. view of the war with Iraq from a European view. Many Americans relish the idea that they are different from the Europeans because of the experience of the American frontier and the cowboy who rode in it; consequently, many Americans promote Frederick Jackson Turner's version of the frontier as a means of defining differences between the U.S. and Europe.

Two prominent news analysts, William Schneider and William F. Buckley Jr., explored how Bush as cowboy was a favorable image because of the positive impression Reagan generated as a cowboy politician. As early as March of 2002 William Schneider, writing in the National Journal, explained how Bush's use of a cowboy image worked to his advantage in positioning himself in the attack on Afghanistan in the aftermath of 9/11. He pointed out that Ronald Reagan also used his cowboy image to affirm his positions by wearing big cowboy hats and using the phrase, “Go ahead. Make my day!” Schneider also explained how Reagan's tough talk about the “Evil Empire” shocked allies and correlated with Bush's own tough talk. Schneider summarized Bush's approach: “Talk tough and carry a big stick, but act with prudence. It's Reagan diplomacy with a Bush twist - just right for an Ivy League cowboy.” Reagan, however, also generated ridicule in the international community with his tough stance and “big cowboy stick.” William F. Buckley Jr. analyzed in the January 24, 2003, National Review what people in the international community found so offensive about Reagan. The diplomatic community, which Buckley claimed “lives and breathes off ambiguity,” was taken aback by Reagan's talk about the Soviet Union being an “evil empire.” According to Buckley, moving forward as a loner with a clear will to take action was antithetical to the international community. Buckley claimed that Bush, if he was like other cowboys, Winston Churchill and Ronald Reagan, would go forward with removing Saddam Hussein from power in Iraq. The cowboy image of Reagan and of Bush for those who endorse Buckley's line of thinking, was not that of the crazed gunman riding out alone, but instead of the man of courage who left ambiguity behind and clearly named the evil doer. Apparently, after the horrendous images of 9/11, the U.S. public was more open to image of the cowboy as a courageous straight-shooting leader than many editorialists realized when they used the word “cowboy” to generate extremely negative associations.

A number of commentators claimed many Americans maintain their love for the cowboy of the Old West repeatedly portrayed in movies and other forms of narrative. Wayne Lutz explored the statements made around the world that portrayed Bush negatively as a cowboy and claimed the statements contrasted with the feelings of most Americans. Lutz provided quotation after quotation referencing Bush as a cowboy and concluded that liberals, “superior Europeans, frightened Canadians, and Al Gore” consider the term cowboy disdainfully and enjoy feeling superior to Bush; but, said Lutz, the American people of the heartland admired the cowboy nature of George W. Bush and calling him a cowboy “stirs the cowboy in us all.” In line with Turner's theory of the frontier, Lutz said America was built by individuals with a cowboy mentality, which meant straight shooting and honesty to most people. The public, Lutz claimed, liked Bush's moral clarity; they admired the fact that he risked an unpopular war, but a war he believed was just. In my opinion, Lutz revealed what should have been obvious in the editorial wars all along: many Americans believe in and love the cowboy. They see the cowboy as central to the identity of Americans and to themselves. We have only to think of the popularity of country western music, of western movies, and the cowboy image in general. When Tim McGraw sings, “I guess that's just the cowboy in me,” he is not anticipating that his words will generate negative associations. Likewise when Ralph Lauren wears a beat up cowboy hat and denim jacket, he is counting on positive associations with the cowboy. So do marketers who use the cowboy image to sell perfume, trucks, and cigarettes.

The love of the cowboy in the U.S., however, did not translate well into other countries, and, in fact, some editorialists analyzed how irksome the love of the cowboy was to many Europeans. Kathleen Parker, writing for Sun News, believed the cowboy spirit in America, based on a love of freedom, troubled other countries. She claimed “most tax-paying Americans grew up watching cowboy shows” and loved what she defined as the “real” cowboy: “the genuine driver of cattle across lonely, death-around-every-corner prairies and torrential rivers [who] was the American heroic prototype - strong, brave, trustworthy, loyal, wise, resourceful, self-reliant and dutiful.” In fact, according to Parker, the word “cowboy” has “become an epithet from the freedom-hating masses.” Parker claimed, “Averring that Bush is a cowboy is like saying he's an honorable man whose word is his bond. Whoa, that hurts.” She ended her article with this statement: “The world has become a global Dodge City. Lucky for us, a Wild West sheriff is in charge.” For Parker, the love of the cowboy translated to the sheriff president who was willing to take charge of his town, the global community. The image of the cowboy acting on the international scene, not just creating law and order in the U.S., seemed to have an appeal for the U.S. public. Robert Kagan in The Globalist approved of the global role of the cowboy president and claimed the U.S. had become a self-appointed “international sheriff” who kept law and order and defeated the outlaws. Kagan viewed Europe as a saloonkeeper, who was not only afraid of the outlaw but also the violent sheriff. If some Americans love the cowboy, and correspondingly George W. Bush as lawmaker of the international community, then perhaps it is not surprising that the press and citizenry of other countries have come to disdain the image of the cowboy and of George W. Bush.

My scrutiny of editorials revealed a belief that Bush took on a largely self-appointed role, and Europeans (in particular the French and the Germans) disdained his will to action. Fernando Oaxaca writing for Latinola's Forum claimed there was a cultural gap between the “French, the Germans and their liberal media sympathizers,” and those who understood cowboys. Vaqueros are the opposite of the wealthy and the elitists, says Oaxaca, and he believes his father, an “old school Mexican,” would have admired Bush's plain speaking and risk taking. Likewise, Andrew Bernstein, a writer for the Ayn Rand Institute, claimed the American public admires the hardworking, courageous, and heroic cowboy. He said when “European critics use the ‘cowboy' image as a symbol of reckless irresponsibility, they implicitly reveal the real virtues they are attacking.” Europeans, Berstein said, disdained the “black and white certainties” and bluntness of the cowboy. They were “worse than the timid shopkeeper in an old Hollywood Western” because they were afraid to stand up to evil and were afraid of anyone else who was willing to do so.

Christopher Hitchens, a Vanity Fair writer and frequent analyst on televised news editorial programs, provided perhaps the most thorough analysis of the use of the cowboy myth and a provocative examination of the contrast between U.S. and European attitudes about it. After proclaiming how frequently Bush had been labeled a cowboy in the European press, Hitchens reviewed the meanings of the word “cowboy”: the tough, fatalistic cattle driver, the uncouth Indian fighter on the frontier, and the lone horseman with a six shooter who held up stage coaches or fought for justice. Hitchens clarified that in England the word “cowboy” “described a fly-by-night business or a shady or gamey entrepreneur” and that cowboys were especially connected to Texas. Hitchens stated, “Boiled down, then, the use of the word ‘cowboy' expresses a fixed attitude and an expectation on the part of non-Texans, about people from Texas.” Regarding the European reaction to Bush's stance on Iraq, Hitchens stated, “What we are really seeing, in this and other tantrums, is not a Texan cowboy on the loose but the even less elevating spectacle of European elites having a cow.” Hitchens' analysis made clear that how one defines “cowboy” was significant in shaping perspectives of George W. Bush and the war with Iraq.

CONCLUSION

I believe the cowboy myth highlights a significant division in perspectives on U.S. foreign policy. Those who view the cowboy as heroic (more Americans than Europeans and, in general, those who adhere to Turner's version of the American frontier) tend to look at political problems in a sharply focused way and are willing to take big political risks in acting on their vision. Bush and conservative editorialists apparently adopted the cowboy myth in order to clarify their adherence to a no nonsense policy on Iraq. Like a sheriff of the Old West who clearly delineates the difference between good and evil, Bush as a straight-shooting cowboy declared the aims of the U.S. were good and those of Iraq under Saddam Hussein were evil. The president was justified, then, in leading the charge for good to win out over evil.

Not everyone, of course, admires the straight-shooting keeper of the law who sees good and evil clearly. Those who view the cowboy as a bad man (more Europeans than Americans and, in general, the New Western Historians) are more comfortable with dealing in ambiguities and complexities and prefer to continue talking and delaying action. They observe the social and political world in a more nuanced way and find the president's unproblematic will to take action very troublesome. They are more likely to look for ambiguities in political and cultural issues and to see less black and white certainties. They view Bush as too eager to take action, and they deconstruct the good versus evil binary he promoted in his 2003 state of the union address in which he sets out his axis of evil.

What I find disquieting is that the cowboy myth has become not only a pattern in the mind but also a pattern on the printed page that generates action. In Regeneration Through Violence , Richard Slotkin emphasizes that myths generate not only thoughts but also action. He defines mythology as “a complex set of narratives that dramatizes the world vision and historical sense of a people or culture, reducing centuries of experience into a constellation of compelling metaphors.” The human mind, as Slotkin explains, generates the myth, but myths “ultimately affect both man's perception of reality and his actions.”

In the case of the lead up to the war with Iraq, comparisons of Bush to a heroic cowboy may have propelled the U.S. into a war in a faster and more determined way than might otherwise have been the case, and thus the use of the cowboy myth in defining contemporary political positions confers additional weight to Joseph Campbell's well-known phrase “the power of myth.”

March 2004

From guest contributor Karen Dodwell, Assistant Professor at Utah Valley State College |