Folks often trot out “stepping into the past” as a suitable cliché to describe wandering through antique shops and looking at artifacts from bygone eras. When they do so, they wish to make clear that the past being gestured toward is not one's own, but rather some indistinct and far-off place evoked by an assemblage of paraphernalia. For me, the child of antique dealers and the grandchild of yet more antique dealers and collectors, these spaces often resemble a trip into my own childhood – which was a kind of cultural study of American collectors and collecting. On one such equally clichéd pilgrimage down "memory lane," I visited a shop on the Tennessee-Kentucky border that I had not entered in six or seven years. I hadn't intended ever to visit the shop again after my first few attempts; it's more of a time capsule than a commercial enterprise. Though its wares are predominantly Victorian, for me it evokes the late 1970s and early 1980s when both of my grandmothers were still able-bodied collectors of the so-called "Greatest Generation," intent upon forging their identities, at least in part, by way of their voracious glassware collecting.

As someone who identifies as a collector myself, I visit many shops, malls, and markets each year; once in a while, though, a shop evokes my childhood in a fashion both nostalgic and vaguely disturbing. This shop, which I won't name so as to avoid causing offense, has become an antique itself, a stage set of sorts. Its prices and merchandise seem identical to what my paternal grandparents were dealing nearly forty years ago. In those days, bric-a-brac was still considered beautiful as the excesses of English and American Country decorating – ushered in by Laura Ashley, Martha Stewart, Mario Buatta, and others – insisted style meant more. Peruse almost any design publication of the era and you'll encounter imposing nineteenth-century cabinets groaning under the weight of massive glassware and earthenware collections. Minimalism had once more given way to abundance and my grandmothers could not have been happier at this acquisitive turn. Of course, minimalism had never really seduced them anyway; as survivors of the Great Depression, less had always meant poverty. Even as they were buying midcentury furniture, they were overburdening it with tchotchkes; like many 1950s homemakers, "stuff" signaled security, stability, and social standing. They never worried about the moral implications of materialism, they stockpiled with abandon.

Stepping into that storefront shop, I could have sworn that those days had returned. Every flat surface was glassware-laden; jewel-toned color groupings mesmerize with their improbable hues and extensive iterations. Never mind that most of it had not encountered soap and water – or seduced a shopper – since Reagan left office. Even in their dusty overcoat, these mass-produced beauties in cranberry, aqua, canary, plum, and so many other hues still manage to captivate. My companions for the trip – two middle-aged academics in town for a visit – asked what I’ve heard so many others wonder: "what do you do with all that glass?!?" "One displays it, of course," I answer. Sometimes one even puts flowers or candy in it. This response is always met with incredulity followed by lamentations about its dusting and having no room or practical use for it. I cannot discredit such criticisms, but I hear them with not a little wistfulness thinking about how that glassware symbolized so much for a generation of women: status, power, (false) security, and influence. Alongside these associations figured their own aesthetic satisfaction and a sense of continuity with the past that such collections established, as they embraced this ephemeral, eternally imperiled decorative art that has become so reviled – just as many household accoutrements that earlier generations considered genteel, if not essential have been – dismissing a once-popular pursuit as apolitical and pointless.

As a result, vintage/antique glassware hardly sells anymore. In that particular "glass house," I spotted at least a dozen pieces that both of my grandmothers would have sacrificed one or more of their grandchildren to own. They have had to, too; the proprietor's voluminous collection has clearly been priced using a long-outdated Kovel’s price guide from a time when the market was robust and buyers lusted after Victorian glass as much as they did pieces from the Great Depression and midcentury eras. They wanted it all. A Fenton plum opalescent hobnail vase in a little-seen form of a short-production color (1959-1962) nestled there among other more common cranberry glass collection sporting pieces from the 1880s to the 1960s, and I'm certain one or both of my grandmothers would have hawked a kidney to take it home. Its asking price was $400 – which he might have fetched at the height of glass mania in the 1980s – and the tag's nearly invisible faded ink suggested it had been sitting there for about as long. I cannot imagine it drawing even a tenth of that asking price today. People simply do not care. Ask antique dealers anywhere, and they all say the same: glass no longer sells. Yes, there are niche collectors of extremely rare pieces, but they're an exceptionally small part of the antique world these days. A houseful of glassware no longer signals refined taste, upward mobility, dedication to American craftsmanship, or an appreciation of the past; in fact, such collections appear to offer the shorthand communication that one is out of touch and unappealingly materialistic. I mourn a bit for my grandmothers and countless other collectors like them at that realization, as that which was once valuable and desirable is now regarded as little more than kitsch.

As a child, my grandmothers instilled in me that glassware was a market that couldn't crack; their entire lives collectors – women, especially – had eagerly sought its endless American incarnations, no matter if it was Flint or Fenton. The U.S. had long enjoyed a booming glass industry, and even in the darkest days of the Great Depression, folks were still eager to amass the various pieces they received as premiums with food and gasoline purchases. They didn't foresee its shattering, which happened near the end of the last century. I grew up surrounded by the stuff; my mother, her sister, all my great aunts, and both of my grandmothers – not to mention countless other people we knew – collected it, though for different reasons. My maternal grandmother, Helen, initiated this trend in 1945; as soon as she set up household with my grandfather, who had just returned from fighting in France, she set about decorating their plain, rented farmhouse. They had little money and my grandfather would not have earmarked any funds to buy what he considered feminine fripperies anyway. His repressive rules were her glass ceiling, at least in the most immediate sense. In her earliest incarnation as a glass collector, Helen was something of a bricoleur, remaking glassware she found at the dump or at church sales into pieces resembling what she admired and could not afford. She regularly painted clear glass various colors – though most frequently black as it was undeniably striking – and then set about decorating the pieces with Victorian-style florals, reminiscent of the English Bristol Glass or the cold-painted milk glass she coveted in the houses she cleaned for money. Those houses were frequently the source of her inspiration because they dwarfed her own modest dwelling. They also hearkened to a time six or seven decades earlier when her family had been the wealthiest in that same county where she and my grandfather now struggled to survive in a house with newly installed electricity and a kitchen hand pump serving as its sole vestige of interior plumbing.

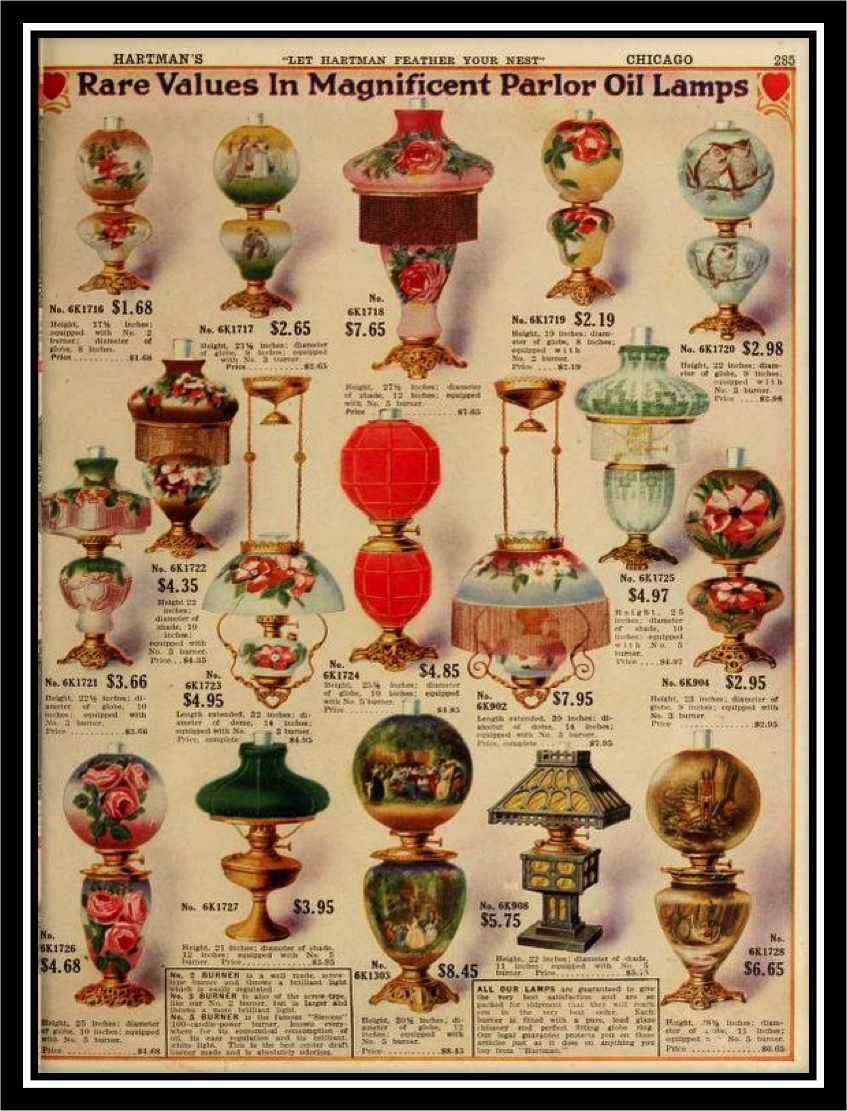

It was not just her family's past that made her heartsick for a time when she might have had a more gracious – not to mention aesthetically pleasing – life though; the movie theaters contributed a great deal, too. She had luxuriated in a theater in 1939 for all three hours and fifty-eight minutes of Gone with the Wind and while she didn’t take away much about the value of human life or the importance of personal dignity, she practically foamed at the mouth over Tara and the other mansions featured in the film. It was then that she first saw the red satin glass oil lamp with its round ball shade – what collectors now call Gone with the Wind or "GWTW" lamps (featured in the advertisement above) – that became her existence's driving obsession. If this seems like a shallow response to the Civil War and its slavery, bloodshed, and destruction, I struggle to suggest otherwise. Gram was not entirely apolitical, though, and her embrace of the beauty she saw in that object wasn't either. She wholeheartedly ascribed to the fundamental importance of kindness and generosity to others and one of the primary ways she transmitted these values – values that can be seen in parts of Gone with the Wind, too – was through the community she created in her home by crafting beautiful surroundings and filling them with delicious food and inviting people in for refreshment, comfort, and friendship.

Hers was certainly no Tara, but she cared about its appearance and like the great William Morris sought to fill it with objects both beautiful and practical. Like him, she believed the world to be a place infinitely improved by beauty. Although I don’t know if she was ever aware of them, I believe she would have loved the Arts & Crafts and Aesthetic Movement practitioners of the late-nineteenth century for their dedication to the edifying and ennobling capabilities of spaces made beautiful, inviting, and comfortable. These ideas, of course, are no longer terribly fashionable and all too frequently the culture of the U.S. especially derides and devalues such pursuits, labeling them feminine and, therefore, unworthy.

Gram, however, was a defiantly feminine person and that red satin glass lamp spoke to her on many levels. First of all, its towering height and impractical color – it would, after all, cast red light unsuitable for sewing, reading, or much else, except perhaps carnal activities – signaled leisure and financial stability. To her, that unelectrified object suggested power and possibility. Poor people didn't generally own such objects not only due to their expense, but also because of their impracticality, a consideration that trumps all else when one is of the working class. Their poorness disqualified, or at least very much diminished, her aesthetic sensibilities as a point of consideration. If they needed light, many of her family members would remind her, lamps could be bought cheaply; appearance mattered little, if at all. What counts, they said, is utility. She wanted both, audaciously, and could not rearrange her mind to accept usefulness as the higher, let alone solitary, value. As a result, she was frequently dismissed as frivolous, impractical, and inconsequential – not unlike those glass objects she coveted are today. Had they been of the moneyed class as her family had once been, however, she would undoubtedly have been more free to create and assemble beautiful spaces and objects, and I seriously question whether anyone would have then treated her as the irritatingly feminine fool that they so often did. It is one thing to recognize or even point out that one cannot afford some alluring object one desires, but it is entirely another to be diagnosed as an imbecile for feeling such an attraction. Her nostalgic yearning for a life filled with more beauty tells so much: it highlights the message we frequently send the poor about expecting less and accepting ugliness; it also magnifies the ways we demean what we consider feminine. Glass, in all its fragility and frequent inutility, shares a similar biography with Helen in its current dismissal and disparagement – a relic of a brand of femininity, at least for now, we'd rather forget. For her family – and wrongly so, I would argue – her aesthetic desire marked her as out of touch, if not ludicrous, because she wanted to recapture, preserve, and promote a past she considered beautiful.

Hers was a masculine-dominated household to be sure, and my grandfather often behaved like a petty tyrant. He considered the material immaterial and dismissed Gram’s wish to live among beauty as the height of absurdity. Thus it was no surprise when, upon the occasion of their silver wedding anniversary, he refused to buy her the "Imperial" style red satin glass (aka "Pigeon Blood") lamp made by the Consolidated Company circa 1880 that she had worked so hard to locate. He laughed at the suggestion and bought her a painted porcelain plate to hang on the wall instead, calling that "too extravagant." By that point in their marriage, he probably could have finagled to give her that single extravagant gift, but he had no intention of doing so. As a result, Gram started to assert herself in unique, and sometimes criminal, ways. She spent a fair amount of time trolling the shelves at Levine's, a local dime store where she had a credit account, looking for the newest pieces – often reproductions – of Westmoreland milk glass in the "Paneled Grape" pattern that was her favorite. The pieces were inexpensive and unquestionably substantial; she reasoned that they could easily have graced a Tara sideboard with their ponderous Victorian proportions and relentlessly undulant fruit reliefs. In her estimation, they possessed a certain nostalgic gravitas as they graciously gestured toward that bygone era.

What's more, for the first time these acquisitions allowed her to compete with her sisters and sisters-in-law, who had joined the 1950s and 60s craze for collecting glassware, especially of the opaque white variety. The postwar economy boom had helped all of them except her enormously, so their collections were well underway by the time Gram joined in on trying to emulate their current decorating schemes. Characterized by the so-called "Early American" style in its most recent reincarnation since the tireless efforts of Wallace Nutting in the 1920s, this style can still be easily glimpsed in countless sitcoms like Leave it to Beaver and Bewitched. This period was the heyday of Ethan Allen's onslaught of patriotic appeal with rock maple Windsor chairs, dough box tables, cobbler's bench coffee tables, and above all, china hutches. Shown off against patriotic-themed wallpapers and so-called primitive accessories like fireplace bellows and brass-banded firkins, these nostalgic, referential, derivative styles helped establish a strong sense of Americanism and solidarity after enduring the horrors of WWII. Whenever that period crosses my mind, I focus particularly on those hutches as the centerpieces of the style with their scrollwork and wide, deep shelves because they were owned by countless women like my grandmothers who crammed them full of the same glassware, often in milk glass.

They embody a certain midcentury variety of middlebrow Americana with their appeals to mass-production, historicized tastes, and limitless bounty. All my great aunts owned some version of that hutch, which showcased their superiority based upon the breadth of their collections. When Gram's sister Marnie died in the late 1960s and her family unceremoniously donated her entire collection to Goodwill, my female relatives keened riotously over the loss. Several even attempted to rescue the glass by repurchasing it, declaring her to be "spinning in her grave" because that glass "meant everything to her." Their glass was an index of their lives. They forged identities based upon their collections and took pride in the patterns they selected and the arrangements they created. They construed it not as mindless materialism or anarchic acquisitiveness – far from it – but as an expression of taste and style. Less is more, magazines like Lonny and Domino edify readers, at least until the market for MCM dries up, and we return to some other model.

While their approach may strike you as ludicrous and misguided, it bears remembering that many of these women, Gram included, had tasted greater freedom and autonomy – albeit briefly – during the war years and being forced into the role of wife and mother – a position insignificantly different from its reality fifty years earlier – left her feeling powerless and short-changed, and rightly so. My overpowering impression of my grandmother and her female relatives and friends is that they wanted and deserved power, authority, and autonomy. They longed to assert themselves and gain some measure of control in a world that had offered them a taste of a different life and then cut them off. It is common to devalue this mode of expression and self-assertion – glass collecting – as silly, vapid even; however, I don’t find the underlying motivation to be so. In this act of collecting and creating beautiful environments, they established themselves as authorities in an arena no one fought them, most of the time anyway, to command – often relying upon narratives of the past employing antiques as evidence for their claims – even when few of the people around them, especially their male counterparts – took them seriously or valued their efforts. They considered them as brittle and easily shattered as the glass they collected, never recognizing the power to persevere in the women or their hard-won collections.

Gram sought to augment her power through acquisition, and working part-time as a housekeeper helped her do just that. It was around this time, the mid-1950s, that her kleptomania took her “collecting” a step further. Her tastes continued to swerve into the high Victorian, and because she couldn't afford such finery she often liberated – by which I mean stole – it, either from relatives or from the houses she cleaned. When she cleaned house, she really cleaned house. She absconded with antiques she saw as undervalued or unappreciated, casting herself as their protector and curator. When she lifted something for which she could not account, she simply reinvented the past by concocting a tale about how this or that object had belonged to such and such a relative. She adored composing a provenance that augmented her own importance as well as the object's. After a while, the past she imagined and the object genealogy she forged became real to her; the nostalgia she felt for all the Porter family had lost was shored up by her increasingly elaborate and delightfully mendacious rendering of a history that existed for her alone.

The best example of her nostalgia-as-coping modus vivendi centers upon a rare and valuable cased glass centerpiece bowl on a sterling silver stand that belonged to the same great uncle who orphaned all that wretched milk glass at the Goodwill. He had inherited the bowl from his mother, a fairly wealthy woman, and Gram had long lusted after it. An ingrate – not to mention a philistine – of his magnitude, she reasoned, had no business holding such a lovely object hostage. She needed to rescue it for its own sake, but also to redress all the wrongs he had perpetrated upon her sister and her possessions. She fretted over its welfare frequently, especially when she fixated upon the fate of Marnie's cast-off collection. When these ruminations became unbearable, she laid a plan to lure the bowl away from him legitimately and then kidnap it, citing its well-being as the cause.

While most people take such measures for children or even pets, Gram was intent upon preserving that bowl from what she considered its inevitable grisly fate were it to remain in that toxic environment. Oddly enough, Curt willingly leant it to her to use at a party. When he requested its return months later, she replied with the lie that she had accidentally broken it. Upon indicating that he wanted the pieces to repair it, she claimed to have discarded them because of their jaggedness. “I’ll take the stand back then,” he said. “I threw it away, too. It has no purpose now either,” she replied. He knew, of course, that a woman who proudly purchased plastic bag-encased shattered glassware to reassemble as though they were 1000-piece jigsaw puzzles had certainly not pitched the bowl, let alone its sterling silver stand, but he could conceive of no way to assail her outlandish claims without inciting outright war within the family, so he desisted.

In the end, she won that particular battle, and Curt only recovered the bowl when, after Gram died, my mother finally repatriated it. It hid in seclusion in the interim, shrouded in a hospital gown (also stolen) in a camel-back Victorian trunk positioned next to her maple hutch. She never displayed it – but we all knew it was in there – though I suspect she must have fished it out of that very adult toybox from time to time for a showing.

In contrast to Gram's willingness to secret away at least part of her collection to revel in privately, my paternal grandmother's collections always had to be featured front-and-center. Just as her gatherings of glassware featured no hidden nooks or crannies, neither did her interior world harbor much in the way of murky motivations. For many years, she could only be accurately described as anti-nostalgic. Raised in an extremely poor and what many have deemed "white trash" family, Catherine initiated married life at sixteen with a lust for only the newest and greatest innovations. Her style was au courant, if cheap, and she had no use for anything with the least bit of age. Photos of her house from the 1950s look like advertisements for The Jetsons, amnesiac in their space-age allusions and lack of historical precedence. When her only child, my father, married though, things changed. My mother had inherited her mother's love of antiques, and she also adored the "Early American" or "Colonial" style furniture so popular at the time, which Catherine always dismissed with the interrogative declarative "that old crap?" She couldn"t imagine anyone choosing it, insisting that "it looks like it belongs in Abe Lincoln's cabin!" her shorthand phrase for something suited to a sewer or outhouse. Her house sported Danish Modern styles, and her sense of self-worth connected intimately with the notion of a life at once "modern" and free of the burden of a past. In many ways, she shared the mindset of many midcentury modernists today: forced minimalism. She had no use for most knickknacks or gimcracks – until she started competing with my mother and her family, that is.

Mom disrupted Catherine's modern stasis in the mid-1960s when she introduced her to Vaseline, a glass made yellow-green by Uranium Dioxide popularized by the Victorians. It fluoresces under black light and proves, if nothing else, perennially eye-catching. Sometimes I see pieces and think they look like the product of a virulent head cold and others, I must admit, prove simultaneously captivating, hideous, and yet somehow lovely. For me, they conjure images of grand Victorian dining rooms, when pattern glass enthralled the masses and companies produced specialized objects for nearly every food and purpose imaginable, from celery vases to pickle castors to honey boxes. I imagine the splendor of endless meals served with thousands of pieces of glassware and revel in the fact that in these daydreams I am the one who eats from those dishes rather than being the one who serves or scours them. Vaseline comes in countless variations: opalescent, hobnail, rigaree, coinspot, thumbprint, and so on. It can be blended with other glasses, as is the case with the ruby and Vaseline concoction called "rubina verde"; it comes in practical serving pieces and purely decorative ruffled dishes; it was both handblown and shaped in molds.

Catherine was incredulous when she first saw it on my mother’s hutch, asking “what’s that old green crap?” Not six months later, she had purchased her first few dozen pieces. Much like Gram with her sisters, this collecting of the past became a point of competition, as well as contention. Though she continually claimed to hate antiques, Catherine suddenly wanted in on the business of narrating history, hopefully showing up my mother in the process. She hated that mom knew what she did not, easily spotting the differences between Victorian-era Vaseline and contemporary reproductions made by companies like Fenton (which called its version "Topaz"). The past was a place she actively avoided remembering, dismissing it as worthless. She couldn't understand how mom knew which dishes served what purpose and when things had no known purpose other than aesthetic appeal. My mother's engagement with the past was partially intellectual as she was curious about these items as historical objects, but she also appreciated their beauty. Catherine, to use a clichéd phrase, was a bull in a china closet intent upon domination, which is its own brand of nostalgia, I suppose, when one considers this motivation likely drove the Victorian glass market in the first place. After all, what self-respecting doyenne of the era wouldn't demand to own every knife rest, salt cellar, and berry bowl available? One couldn't have one's neighbors thinking they were the only ones not sporting a helmet butter dish or a beggar's hand toothpick holder on their breakfast table, after all.

At the height of her Vaseline vendetta, Catherine amassed a collection of nearly 200 pieces. Her crowning acquisition, sadly, came at my mother's expense: in a pinch, she was forced to sell Catherine her most cherished pieces which included a child's opalescent Vaseline creamer. Catherine underpaid for the pieces and whenever I visit her house I eye them with nostalgia as I know their forfeiture financed a happy Christmas for me and my siblings that year. Oddly enough, those were her last Vaseline acquisitions; she had purchased mom's past and the history it symbolized, both personally and on its own merits, and then entombed it in the corner china closet – ironically hand-built by my father – in her living room, assured that she now controlled that narrative. Her collection and collecting asserted her power and ability to control the situation, to assert dominance and definitiveness about what the objects meant and how they could signify.

Vaseline was not her last pass at glass collecting, however. As that collection remained static, she and my grandfather, uncharacteristically, entered into the antiques business, at least in part, so that she could build collections to outdo mom's. In a move not unlike young idealists who turn conservative once they gather a little money, my grandparents bid minimalism farewell and submerged themselves neck-deep in late Victoriana. This was in the 1970s when people were just starting to hanker for a return to the excesses of the late nineteenth century furniture that would enjoy its peak revival in the 1980s. This, of course, preceded the current mode of preserving antiques in their found condition and enjoying their patina. No, the fashion then, and it spoke to my grandmother's former mania for newness, was to refinish those unruly pieces into absolute submission, erasing their lived experience and the palimpsest of their history. While my grandfather spent his weekends scouring auctions for likely victims, my grandmother labored away in her torture chamber stripping off original finishes and replacing solid brass hardware with plated reproductions glaringly bright enough to guarantee retinal scarring. If this were another kind of essay, I would pause here to insert a number of "grandma the stripper" jokes, but we will have to traverse that road another time. Suffice it to say, however, that I have made them all my life, and mostly while remembering her with a wire brush and steel wool assaulting furniture in ways that any soul with an ounce of sensitivity would deem an unnatural act. This newly refinished furniture, she felt, served as the perfect backdrop for her glass collections.

Within a year or two her house transformed from a 1950s nightmare into a quasi-Victorian hellscape replete with newly revarnished golden oak pressed-back chairs, bow-front china cabinets, and high-back beds as far as the eye could see. Once she had installed all this furniture, though, she faced endless questions from her friends about why she'd chosen that particular style, and what it symbolized for her as it was so radically different from her earlier décor incarnations. Curiously, or so it would seem if you didn't know her, she could offer no plausible explanation. In fact, she was baffled that people figured her sudden trip down what they assumed to be her "memory lane" had been prompted by some internal longing or nostalgia. She had done it because other people (including my mother and her family) were doing it and she wanted to outdo them, to create a rival history, so she wouldn't feel excluded. Rather than inventing a fiction to satisfy their tiresome questions – a venture for which she didn't really have the imagination – she started to collect Depression Glass to deflect questions about her new old furniture.

If you have ever visited an antique store, flea market, or charity shop in the U.S., chances are that you've seen Depression Glass, which was produced in this country from the late 1920s through the 1940s as premiums to encourage customers to spend money on staples like food and gasoline during the Great Depression. It reached peak popularity as a collectible in the 1970s and 1980s, likely because of women like Catherine who had lived through those lean years and whose families had often owned pieces of the pink, green, cobalt, and amber glassware. While it came in a range of colors, patterns, and styles, the pale pink and green have always been the most popular, followed immediately by the cobalt. When she could not account for her sudden alteration in furniture taste, Catherine became a collector of the green glass because her sister had once mentioned that their grandmother might have owned a piece or two of it.

For a woman who dedicated the majority of her adult life to avoiding any acknowledgement of her past or having experienced a childhood, Catherine was suddenly in the memory business, late in joining the game as she was. She bought green Depression Glass by the truckload and filled multiple golden oak Victorian kitchen cabinets with the stuff. As a child, I was always fascinated with the Anchor Hocking “Block Optic” sugar and creamer that served as the centerpiece for her kitchen table because they sat on their own stand with a large glass handle in the center.

"This was popular when I was a kid," she would volunteer once in a while. When I took an interest as a young teenager and pressed her on whether her family had owned such items, she seemed uncertain and mentioned that Aunt Rosie thought their grandmother might have owned a bowl. I had not expected her disinterested response considering that she had alluded repeatedly to the fact that it somehow represented her childhood. I struggled not to imagine that as the motivating factor for her buying hundreds of pieces of the stuff. She also owned numerous guides to the pieces and their values. She had replaced every imaginable kitchen implement including salt and pepper shakers, mixing bowls, reamers, refrigerator boxes, etc., with it, presumably because they evoked something appealing about her childhood despite it being during the difficult days of the Great Depression.

I was fascinated and loved the kitchen pieces, in fact I own several today, but she seemed to possess no real feeling for it or any genuine interest in its history. Rather, she only enjoyed gesturing toward the collection as something that should evoke her past without ever really engaging with it. It was something to lord over others; it gave the impression that she was the sort who possessed a feeling of sentimentality or nostalgia. It also nourished her love for acquisition and domination. What's most funny, though, is that she seemed best pleased when my grandfather would tell visitors that while "that green stuff" used to be given away for free, now it was worth "a pile." I always took that as a hemorrhoid joke because it very likely could have been from him, but she did not. She believed he meant "very valuable." If nothing else, those items conferred status on her in those years when they were considered valuable which, sadly, is no longer the case. These days, I see those pieces at flea markets priced so cheaply that she would be incredulous; those pieces that once bolstered her sense of power and position now sell for virtually nothing, if they sell at all. Seen in that light, her massive green glass collection certainly invokes "depression."

Though such decorative and utilitarian objects are easily dismissed out of hand these days, that spurning is, in itself, a recurrent trend in the American collecting scene. Every decade or so a media mandate appears to disperse or develop collections; right now glass is the collection collecting dust in antique stores and flea markets, its disavowal a clear indicator of refined taste. As an avid reader of decorating magazines all my life, I like to make a habit of spotting attempts to revive and rejuvenate certain kinds of collecting and trends in decorating. Every few years for the last decade or so, one brave editor or another will work up a piece on glass collecting. In part, I think this happens because folks with mindsets similar to my own walk into shops like the one I describe in the introduction and feel nostalgia, remembering the fervor with which their elderly or now-deceased family members approached collecting and displaying glass. It’s also likely a practical, capitalistic consideration: the market has completely bottomed out for decorative glassware and its abundance means, at least theoretically, that readers with emulation aspirations could more easily build a collection of such items because of their availability and (sometimes) low prices than they might with objects in categories currently deemed more desirable. In other words, there's a huge supply because there's very little demand, and having spent a lifetime in this world I know well that some people just want to collect because it's trendy or hip, whether they feel a true affinity for the objects or not. If buyers could be spurred to collect, the market would improve. For the last decade especially, magazines like Country Living have tried multiple times to make all that 1950s milk glass cool again. If anyone is interested in hopping on that particular bandwagon, I will gladly point them to a local antique mall booth near my house that features hundreds of pieces at reasonable prices. One person out of all the collectors I know – and I know many – participates in this "trend," though she never violates her vow to spend no more than $5 per piece. She collects milk glass for the same reason I feel some connection to it: her poor grandmother considered it her pride and joy. Its abundance shored her confidence up against a nagging sense of scarcity. As for the rest of those supposedly easily influenced readers they seem to have their resolve steeled against it; they find its appeal anything but crystal clear.

It would be easy here to point out that both of my grandmothers, to varying degrees due to the disparities in their disposable income, actively inculcated themselves in the rampant consumerism of the 1950s. One might even argue that they functioned as mere extensions of the Victorian era, fiendishly acquiring (mostly, though not exclusively) machine-made glassware that often served no utilitarian purpose and did little to exalt themselves into the realm of some high aesthetic. Collectors today, from my observations, seem to believe that in repudiating this glassware, they consciously reject the housewifery and domestic subjugation coupled with mindless, unsatisfying consumption that many contend characterized the lives of women of that generation, and Victorian women, especially of the middle class, too. There is truth there, I concede, but such a reading flattens out context and reduces lived experience in ways I find shortsighted and unsavory.

When I see that antique and vintage glassware today, I do not conjure callous consumption or unconscionable collecting. I think about two very different women with whose life circumstances I am intimately acquainted and who resemble countless other collectors I knew; I recall their endless struggles to be more autonomous and impactful in a 1950s rural Midwestern community that was having none of it. I also chuckle slightly when I focus upon how fashionable it has become today for collectors to pursue objects with "soul" or a "story" to showcase in their homes as totems of their individuality and refined personal aesthetic. They rely upon those "finds" to telegraph so much about their individuality and place in the world without ever recognizing that much of that glass served a similar role in the lives of the women, and some men, who collected it. The irony of this situation becomes even more comedic when I see all those Midcentury Modern collectors waxing eloquent about clean lines and minimalism, never realizing that most of the homes that sported the furniture accessorized it with the very glass that so easily glazes over their eyes. Those collectors, like the rest of us, elide certain elements of the past that prove irksome in favor of a self-serving narrative. I don't fault them for this – it's a survival strategy – but I wish they would approach those with other aesthetics and objects of fascination with more care.

In reminiscing about the nostalgic pursuit of collecting glassware, I have discovered that engaging with the past – even a highly fictive, self-styled version – promotes the possibility of instituting orderliness and beauty. It is escapism, yes – nostalgia always, by its very nature, is inescapably that – but not simple escapism free of complexity or a demand that we continue to engage our present circumstances regardless of how we wish we might to escape them altogether. But it also offers the opportunity to instantiate some element of a past that proves alluring or captivating into a present the frequently seems much less so, diminishing and dismissing anything involving the decorative or pretty. For many collectors, a genuine and fascinating emotional connection to objects in the world around them animates and enlivens their desire and their engagement with the spaces they inhabit. I construe this not as the base materialism so often derided in our culture today; rather, I see a profound attachment to an object or objects they considered beautiful and edifying. This proves a highly individualized and imaginative experience that may rankle those historians who rail about authenticity and accuracy as these pursuits transpire in a kind of lawless, freeform engagement where objects and their uses and values may be put to ends which prove at once foreign and run counter to traditional narratives. This is, in the final analysis, in the world of collecting, the work of nostalgia – and it proves beneficial and productive for us all if only in the sense that it safeguards such objects and ensures their preservation as flashpoints of beauty, inquiry, and conflict for the future.

When I encounter that glass, I think about my grandmothers’ motives for pursuing, gathering, and displaying it. I think about two different women – one I admired, the other I do not – and the ways they labored to create a narrative of history and place – genealogy, even – by collecting objects they found meaningful and/or powerful. Gram was clearly focused upon it because she believed it to be beautiful and she appreciated the way those physical objects – at least in her mind – represented a variety of grandeur her family once enjoyed and then lost. All that glass symbolized that she was more than she got credit for, both individually and as part of a family that never quite appreciated her hard work and generosity. She did not believe living in beauty to be a luxury for the rich, she wanted that for herself. Catherine's motives were somewhat similar to Gram's, but she experienced far less cathexis with the objects she amassed. Nevertheless, she was also interested in establishing a more robust, interesting family history and bolstering her status, even if only within our family and small community, by way of the authority she felt collecting leant her. They were women of their time seeking avenues for greater fulfillment and empowerment, I believe, and we should not be so quick to dismiss or denounce their methods even if they look at least somewhat suspect to a contemporary eye.

For those people old enough to remember those fanciful creations as legitimate commodities, not bibelots waiting to be broken – and there are a few still around at antique markets and malls – these are curious times when all that was solid underwent a paradigm shift and suddenly became démodé. Young and middle-aged collectors now crave industrial antiques, advertising wares, and Eames chairs. The glass diehards' price tags sometimes evoke an earlier era – like those at the shop near my house – as they exist in a delusion that someone will surely pay a paltry $995 for an exquisite hand-blown amberina epergne. To what has the world come if that’s not true? They don't grasp that virtually no one even knows that word or the purpose of such an item. When it's not a fantasy price tag, sometimes it's a clicking tongue or a soft lamentation one hears about "how much that used to be worth." Other times it's a hopeful utterance, perhaps even a prayer of sorts, about glass "coming back," but it doesn't seem likely as the epigram from Franklin reminds us. The glass market has cracked, and probably for good. Catherine, for her part, long out of that market, still lives in her glass house. She holds court in her midcentury-late Victorian mishmash living room, decreeing that her heirs will appreciate her anew when she passes if only for all the money that glass will command at auction. I'm grateful, though I cannot say exactly why, that she will never discover that women now prize more overt manifestations of autonomy; in so doing, they finally settled that age-old question about glass: it isn't half empty – it's aw-full.

April 2017

From guest contributor Joshua Adair, Murray State University |