(Social) space is a (social) product...the space thus produced also serves as a tool of thought and of action...in addition to being a means of production it is also a means of control, and hence of domination, of power.

– Henri LeFebvre, The Production of Space

In Street Dreams, bestselling Street Literature author K'wan constructs an urban world where much of the action takes place in less than ten blocks. Set in the Upper Westside, Manhattan New York, Frederick Douglass Public Housing projects, K'wan immediately situates Rio, the drug dealing main character, generally “against the project building" and more specifically by “the courts on 104th between Columbus." K'wan, however, doesn't just describe his setting and then leave the reader there, but carefully guides us through this highly location-specific world. In the first chapter, Rio, a part-time spot manager, walks with the area's biggest drug kingpin Prince “toward Central Park West, past the end of the projects and across Manhattan Ave." Correspondingly, in the first line of the second chapter when we meet Rio's girlfriend Trinity, she is sitting “inside the library on 100th Street, trying to make heads or tails out of the GED prep book" before following her as she strolls up 100th street.

This emphasis on particular, real locations, especially landmarks and streets, is consistent throughout Street Dreams. Rio drops Trinity off at the “doorway of 845"; he gets off at the “103rd Street Station"; his friend Shamel's building is at “107 and Manhattan"; and he frequents “the liquor store on 105th" (emphasis mine); and “the little Spanish restaurant on 104th" (emphasis mine). In these last instances, the definite article is especially important – it is not a little Spanish restaurant but the specific one on the specific corner. While Street Lit books are often lumped together as tales of the inner city, they actually represent particular stories grounded in particular spaces, and these streets, corners, and landmarks are as much a part of the story as the characters. As such, in Street Dreams, specific landmarks from this neighborhood are frequently referenced – “St. Luke's Hospital on 114th and Amsterdam," “P.S. 145's park" – until this book almost serves as a map of the Douglass projects and its immediate surroundings.

As is true of other Street Literature novels, in Street Dreams setting is more than just a shout out to specific places. While in these novels authors “rep" or represent their homes in a similar fashion as many hip hop artists, this particular localization of place delineates a strict and carefully constructed narrative world – a space where the ghetto is also a main character. Place names, then, in Street Literature not only serve as territorial markers but also as indicators of the unique social space of the ghetto.

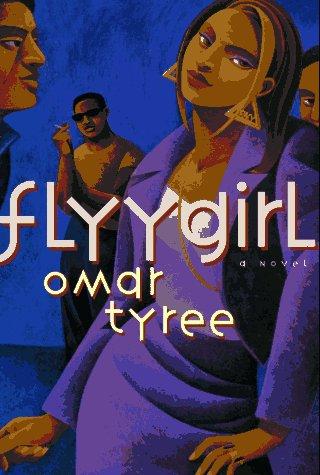

Since the late 1990s, Street Literature, also known as Urban Fiction or Ghetto Lit, has emerged as a new type of African-American popular fiction, mainly distributed through self-publishing and street vending. Initiated by Omar Tyree with his novel Flyy Girl in 1993, Street Lit became prominent with the bestseller The Coldest Winter Ever written by the activist and author Sister Souljah in 1999. However, the genre's popularity really began to grow with Teri Wood's True to the Game, also in 1999. Now a New York Times bestseller of millions of books and the owner of her own publishing company, Woods began selling her novels out of the trunk of her car in Harlem. Today, there are hundreds of authors selling their books through a variety of methods from street vending and self-publishing, to independent publishing houses, to larger publishing houses like Random House's Urban Literature division. In fact, according to Almah LaVon Rice, among black bookstores in the US, “street lit accounts for almost all of the current top-selling paperbacks."

Despite forerunners ranging from the street toasts of the 1930s and the street-themed fiction of the 1950s, 60s, and 70s, the commercial success of these novels - a success which has forced major publishing houses to create urban literature divisions - is unparalleled, except perhaps by the rise of hip hop in the 70s and 80s. In many ways, Street Literature is very much an outgrowth of that music, similar to the emergence of the hip hop press and cinema. According to Earni Young, not only do these novels deal with much of the same subject matter – drug dealing, gang lifestyle, poverty in the inner cities, housing projects, female sexuality – and share many of the same themes – sex, violence, partying – they even share authors like 50 Cent and Snoop Dogg. Both simultaneously consumed in marginalized neighborhoods and attacked for "dumbing down" African-American culture, these representations of life in the "ghetto," from education to crime to the prison system, are a powerful illustration of how a significant segment of the population views and consumes race in America.

Like hip hop, Street Literature allows for both reflection as well as disruption of the common stereotypes about popular black culture and inner city experiences, however, as novels and not rap, they also create a greater opportunity for depth especially in terms of character and setting. Street Literature creates new spaces of self-representation that both perform the “authentic blackness" defined by popular culture (including hip hop) and mass media at the same time that they powerfully reject the culture that has placed these stereotypes upon them. In his pioneering study of space, Henri Lefebvre writes: “To recognise space, to recognise what 'takes place' there and what it is used for, is to resume the dialectic; analysis will reveal the contradictions of space…in the route from mental space to social space…[in the] specific contradictions…between centres and peripheries…in political economy, in political science in the theory of urban reality, and in the analysis of all social and mental processes." Although written in 1976, these contradictions and conflicts of space as well as the production of unique social spaces in and through Street Literature are key to analyzing today’s urban reality, more than thirty years later.

A Theoretical Basis: Murray Forman, Henri Lefebvre, and Edward Soja

Murray Forman argues in The 'Hood Comes First: Race Space, and Place in Rap and Hip Hop, that a spatial perspective is a key component in analyzing hip hop, yet one that has been understudied. He writes: "At the core of this book is the belief that by examining and exploring the multiple articulations of the terms 'the ghetto,' 'inner city,' and 'the hood,' as well as other key spatial configurations that emerge from rap’s discourses and hip-hop media generally, the cultural production of urban sites of significance can be illuminated. It is too frequently accepted without evaluation that rap is implicitly conjoined with spaces of urban poverty, existing as a both a product and a legitimate voice of a minority teen constituency that is also demographically defined as part of the social 'underclass'."

As Forman notes, while much academic attention has been paid to examining hip hop’s history and geography in terms of its origins, little attention has been paid to analyzing its unique spatial discourse. There is a similar lack of attention to studies of Street Literature. Although much attention has been given to Street Literature's increasing popularity and controversial subject matter, a deeper analysis of these self-representations of black and Latino inner-city life and the new discursive spaces they open has yet to be explored. Although not the only method to analyze Street Literature, the lens of space and place provide a useful entry into further explorations of race, sexuality, and gender because of the powerful spatial logic that permeates the genre. Thus, in this article, I will explore various spatial approaches in order to highlight both how Street Literature interacts with these various discourses (including hip hop) as well as opening up a new narrative space of inquiry. As Street Literature both combines the influence of hip hop and rap as well as the opportunities of a longer written format, the streets of Street Literature are able to become uniquely urban and global, real and imagined, in place and out of place.

Written at the same time as Street Literature's emergence, Edward Soja's works, Postmodern Geographies, Thirdspace, and Postmetropolis, take up Henri Lefebvre's propositions about the social nature of space, applying it to the urban world. Moving away from a dualistic historical and social approach, Soja argues for the “inherent spatiality of human life" as a third, although not separate way of understanding and examining society. Thus, based on Lefebvre's "trialectics of spatiality," composed of “the perceived space of materialized Spatial practice; the conceived space he defined as Representations of Space and the lived Spaces of Representation," Soja proposes a more encompassing “thirdspace." In this thirdspace, not only do Lefebvre's three spaces merge, but also the social, historical, and spatial forms of thinking, the real and the imagined. Interestingly, it is also this convergence that Murray Forman seeks out in his analysis of hip hop, and which Street Literature authors present with their fictional representations of so-called "real" life in the ghetto, set in existing public housing spaces and specific inner-city streets.

As Soja describes, Lefebvre's spatial critique originally came out of the recognition of the alienation and “the uneven development which characterizes every aspect of our era," a view not far from the spaces portrayed in Street Literature. Correspondingly, Soja's three conceptions of space as built from Lefebvre are useful in employing spatial approaches to this genre. Soja begins with Lefebvre's perceived space which he redescribes as “Firstspace," “a materialized, socially produced, empirical space." As the most basic of spaces, this corresponds to Forman's critique about the unanalyzed geographies of hip hop, which focus on specific locations as historical markers of the music's development. Although this concept becomes more complex within Street Literature - which did not develop in correspondence to specific cities, but is found in urban areas across the nation - the connection to the inner city is key. These easily classifiable urban places not only serve as settings in Street Literature but as commercial spaces, both on street vendors' corners and in bookstores.

In Soja's Secondspace (based on Lefebvre's conceived space) we find "the primary space of utopian thought and vision, of the semiotician or decoder, and of the purely creative imagination of some artists and poets." Referring to "language, discourse, texts, logos," at this level, space moves into the mind and representations of power. Here, we find the contradictory representations of what constitutes ghetto space in Street Literature. As Terri Wood's landmark novel True to the Game imagines, the ghetto is a place that cannot be escaped, yet also has an indisputable draw. In the opening scene, for example, the main female character Gena goes to Harlem, a famous ghetto setting where she meets the main male character and drug dealer who will become her boyfriend. Nevertheless, despite growing up in the well-known Richard Allen projects of Philadelphia, she is able to move out at seventeen with the help of her uncle. Simultaneously desperate to leave the “hood" and yet drawn to the lifestyle, the imagined space emerges. Gena describes Philadelphia: "That was one thing Gena could say for herself. Even though she was raised in the projects, she had family who believed in taking care of the kids. Some people didn’t have family like that, and Gena knew it. Some parents didn’t give a f--- one way or the other. Do what you gonna do, 'cause you gonna f--- something up anyway. That was the attitude. Half of Gena’s friends had parents who said, “Hey, we got a party to go to," and that's where they were, at the party partying. Or if they weren’t at the party, they were too busy getting high. Then you had the motherf------ sitting right there in the house not giving a damn whether the kids were in the house, in the street, hungry or safe. A whole generation sat back, and said, 'F--- it. I'm not gonna raise my kids." Here, Gena simultaneously converges her firstspace knowledge of the place of Richard Allen Projects, with her secondspace view of life in the projects, based on what she describes as the lives of “some people" and what she imagines as the norm. In Gena's vision is where firstspace and secondspace converge in Street Literature – the lived space that is both real and imagined.

Soja links the two in thirdspace where space is “directly lived" - combining “all other real and imagined spaces simultaneously." Likewise, Gena both describes her reality and the imagined space of the projects, which is both based on her own experience and socially produced through the hip hop culture, the media, the history of minorities and urban settings, and mainstream society's expectations. This link between the real and imagined is key to understanding Street Literature. Often dismissed for glamorizing a ghetto lifestyle, Street Literature concurrently deals with the harsh realities that have ravaged specific places - specific cities, neighborhoods and projects - as well as the realities of the characters' own lives, imagining the ghetto as both a free-spending party and one in which a drug epidemic has ravaged families.

Sister Souljah's The Coldest Winter Ever powerfully demonstrates the convergence of real and imagined space for its main character Winter, the daughter of one of the largest drug dealers in Brooklyn, Ricky Santiaga. When Santiaga moves his family “out of the ghetto" to Long Island, Brooklyn becomes a place of longing for Winter who is endlessly attracted to what she perceives as the quick money, endless spending, hard partying, fast-paced lifestyle of the hustler. She imagines the streets in a very particular way, which the novel contradicts through the course of the narrative. Despite how Winter imagines “the streets," it is this lifestyle that ends up landing her father and herself in prison, splitting up her sisters, and leaving her mother as a crack addict. It is a reality her father tries to express to the headstrong and naïve Winter: “Do you think those streets love you? Those streets don't love you. They don't even know you. You could walk those streets one thousand nights and one thousand days and they wouldn't even know your name. The streets don't love nobody." As The Coldest Winter Ever demonstrates, the streets are a powerful space that is actually anthropomorphized – no longer a place, but almost a sentient being.

Soja's argument in Thirdspace that - “There is no unspatialized social reality. There are no aspatial social processes." - is clearly represented by Street Literature's spatial narratives. But, these all-encompassing spatial logistics of thirdspace can also be limiting. As Soja explains his concept, thirdspace is about inclusion: "Thirdspace is the space where all places are capable of being seen from every angle, each standing clear; but also a secret and conjectured object, filled with illusions and allusions, a space that is common to all of us yet never able to be completely seen and understood… Everything comes together in Thirdspace: subjectivity and objectivity, the abstract and the concrete, the real and the imagined, the knowable and the unimaginable, the repetitive and the differential, structure and agency, mind and body, consciousness and the unconscious, the disciplined and the transdisciplinary, everyday life and unending history."

In some ways, this appeal to universality loses the particularity of Street Literature. Furthermore, despite Soja's insistence of the inseparability of the historical, the social, and the spatial, Street Literature is notably ahistorical. In these youth-oriented narratives in which the main characters are rarely over twenty-five, parents and grandparents are scarce as well as any real consideration of the crack epidemic or drug wars, even with the extreme particulars of the novel's space. Instead, the focus is almost always on the present – getting rich now, partying now – with very little planning for the future.

Kermit Campbell's analysis of Street Lit forerunner Donald Goines and 1970s black cinema is equally relevant to these novels. They present “ghetto realism," offering two possibilities in life, neither of which encourage thinking about the past or planning for the future. In his analysis of Goines' novels, Campbell writes, “One has only two choices, neither wholly desirable. One may settle for membership in the ghetto's depressed, poverty-stricken silent majority, or opt for dangerous ghetto stardom." Already this trajectory is clear from the novels highlighted: Rio in Street Dreams, Winter in The Coldest Winter Ever, and Quadir in True to the Game opt for ghetto stardom and die or end up in jail. For Rio, this constricted space is even more poignant. A college graduate, he attempts early on in the book to find legal work and is portrayed sympathetically as being left with no other choice but drug dealing because of his criminal record: “In today's world a blemish on your record could follow you for the rest of your life. Without an income and lack of opportunity, some youths turn to the streets to get on. At that moment, the streets didn't seem like a bad idea to Rio."

Clearly, spatial thinking, in terms the opportunities and limitations of the novel's settings for the characters (and in many ways the authors) both real and imagined, is central to Street Literature. Although set across the United States, the settings from New York to Los Angeles to Chicago to Detroit, all share the existence of a substantial minority inner-city population. There is no rural Street Literature. Similarly, it is noteworthy that from Thirdspace, Soja follows with Postmetropolis: Critical Studies of Cities and Regions in which he applies his concept of thirdspace to different ways of studying urban centers. Here, thirdspace becomes “cityspace" a reference to “the city as a historical-social-spatial phenomenon" that emphasizes “the spatial specificity of urbanism." In what follows, Soja introduces six different yet interconnected representations of “new urbanization processes": Postfordist Industrial Metropolis, Cosmopolis, Exopolis, Fractal City, Carceral Cities, and Simicities. Although his discussion of the “Fractal City" approaches issues of economic inequity as well as ethnic and racial marginalization present in Street Literature, Soja's overarching view is very different from the extreme localism with which Street Dreams opened this article. Soja writes, “Cityspace is coming more and more to resemble global geographies, incorporating within its encompassing reach a cosmopolitan condensation of all the world's cultures and zones of international tension." Although this may be true, the urban worlds of Street Literature are highly homogenized, strictly structured ones in which the characters are almost all of one race, age group, socio-economic background, and often times one public housing building.

Street Literature as a Response to Urban Marginalization

Despite the globalization of both the hip hop and Street Lit markets, the worlds presented stand in stark contrast to the “urban reality" as presented in Soja's global cities and macrospatial point of view. In other words, the imagined spaces of Street Literature have something very different to say about the way space and place exist in the hood. In Street Dreams, where the space is so carefully described and restricted to ten or so blocks on Manhattan's upper west side, there is also a recognition of the closeness of the other world where space – both real and imagined – is completely different. As Rio and his boss, Prince, the area's largest dealer, note: "The walk from Columbus to Central Park was like walking through an evolutionary scale. Where the projects ended, walk-ups and little townhouse-like structures began. The townhouses ended making way for luxury apartments. It was like steeping into a whole new world in a few short blocks. Prince stopped near the mouth of the park and took in the scenery. White folks were walking their dogs, riding bikes, and doing all sorts of outdoor activities. All carrying on as if they were oblivious to the fact that there were crack-infested housing projects a block away."

Over and over, this contrast in Street Literature – the tiny radius of the settings, the specificity of the standings juxtaposed with the greater city outside (downtown where Rio can't get a job, Long Island versus Brooklyn for Winter) – creates a powerful discourse of the marginality of space. Accounting for this, Soja also describes his thirdspace in terms of difference or “thirding as othering" where “thirding introduces a critical 'other-than' choice that speaks and critiques through its otherness." From this point of view, Street Literature can also be seen as presenting an alternate worldview and value system in response to urban marginalization. Prince's awareness of the closeness of a richer, white population divides the world of Street Dreams on spatial and social terms. Interestingly, at least for Prince and other characters like Winter's family, it is financial success through that drug trade that allows them to break these spatial and social barriers and move into “white" neighborhoods. Ironically, it is also their very alienation from these “white" spaces, as demonstrated by Rio's job rejections, that propels him to seek out the type of employment that allows them to live outside of the ghetto. Similarly, the four male protagonists of Street Team, Butter, D-Mac, Wu, and Flip, move from building 1839 in the Morris Heights section of The Bronx to New Rochelle, creating an important distance from their families and the neighborhood where they both grew up and sold drugs.

For Street Literature, the key for these characters is what they see as the distinction between marginality that is imposed upon them and marginality they choose. Some characters like Rio struggle with this conflict, while others like Winter see no other life but street life. More importantly, the books are framed discursively in this way. Two main types of characters are presented – the poverty stricken inhabitants and those who take part in illegal activities, and for the latter their choice to engage in these activities is a rejection of the society that has rejected them. In his analysis of “socio-spatial differentiation," Soja examines bell hooks as an example of “choosing marginality" through her construction of “radical black subjectivity" as a form of resistance. Soja writes “For hooks, the political project is to occupy the (real-and-imagined) spaces on the margins, to reclaim these lived spaces as locations of radical openness and possibility and to make within them the sites where one's radical subjectivity can be activated and practiced in the conjunction with the radical subjectivities of others." For instance, according to the back cover of Street Team, “Joe Black tells a tale of four ghetto youths who refuse their small piece of the so-called American pie, and instead decided to stick up a bakery. A rags to riches tale." This simultaneous acknowledgement and rejection of societal values is part of “choosing marginality." As hooks describes it, “We looked both from the outside in and from the inside out. We focused our attention on the center as well as the margin. We understood both. This mode of seeing reminded us of the existence of the whole universe, a main body made up of both margin and center." Thus, although ignored by the richer, white populations nearby, Prince is keenly aware of them as the center, and his world at its margins. Similarly, the four youths of Street Team refuse the center, “the so-called American pie," but acknowledge its existence by moving out of the Bronx to New Rochelle. Set at the margins of society, the world of Street Literature thus reveals the value systems of spatial organization – they choose to embrace their places both because they have no other, but also because the characters are drawn to street life.

Tim Cresswell examines sites where place and value are closely aligned – what is accepted in one space (social, economic, gender) is not necessarily accepted in another. Particularly important in his study, In Place/Out of Place, is the idea of transgression and the ways in which what is considered transgressive from the margins can highlight ideas of normativity. Cresswell gives the example of graffiti artists who have their own set of rules, beginning with apprenticeships and what places they can mark, rules which are not recognized by the law: “Because New York City government has the power to enforce its rules on the graffiti artists, it is the graffiti that is labeled deviant. In the same way the rich make rules for the poor, blacks' actions are defined by whites, and appropriate behavior for women is adjudicated by men. Power, in many ways, is the ability to make rules for others." In this view, specific places also become a site of particular value systems.

Although Street Literature, like hip hop, has been criticized for portraying negative stereotypes of black men and women, in the world of Street Literature the particular value systems associated with its main social space, the ghetto, are clearly defined. Thus when describing 1970s Street Literature writer Donald Goines, Campbell highlights some of the genre's rules: "Zero-sum-game societies," where one man's gain must be another's loss and survival without criminal activity is impossible, and "the Ghetto Golden Rule" where what goes around comes around." As Street Dream tellingly narrates, “One thing Trinity had learned from spending so much time on the streets was that one man's misfortune is easily turned into another man's fortune. Well, in this case, woman's." In the same way, although Winter ends up in prison, she has no remorse nor does she even feel a need to warn her sister, who seems to be following the same path. Instead she keeps “several hustles" to improve her life while incarcerated. For Butter, D-Mac, Flip, and Wu of Street Team, there is never a look back or a consideration of any other life, and all but Butter end up in jail.

What is key here is the way these narratives formulate an alternative value system in terms of employment, relationships and life outlook, which is unique to the ghetto space. Forman notes: "Within hip-hop culture, artists and cultural workers have emerged as sophisticated chroniclers of the disparate skirmishes in contemporary American cities, observing and narrating the spatially oriented conditions of existence that influence and shape this decidedly urban music. It is important to stress the word 'existence' here, for as hip-hop's varied artists and aficionados themselves frequently suggest, their narrative descriptions of urban conditions involve active attempts to express how individuals or communities in these locales live, how the microworlds they constitute are experience, or how specifically located social relationships are negotiated."

As Forman reminds us, Street Literature, like hip hop, emerges from the contradictions and convergences of real experience and knowledge and the way these "real" experiences are imagined, constructed, and represented through the physical and “symbolic city." Thus as opposed to the ghetto, which Forman finds as negatively imagined as a racialized slum representing urban blight, the “hood" is able to emerge as a different “area of experience" that represents “lived experiential environments" or “home." In his analysis, the ghetto remains abstract and “framed by much of white Americans' perceptions of black urban dwellers, regardless of their class status," while the hood opens up a new discourse that both encompasses the same physical space of the ghetto and allows for the particulars of location and individual identity. Thus when Trinity says, “I don’t worry about stuff like that. I mean, I know the streets are dangerous and all, but danger lurks everywhere. If I can’t feel safe in my own projects, I can’t feel safe nowhere," she expresses both these representations: ghetto as urban blight and hood as home.

Authenticity and Reality: From the Streets to the Presses

From Trinity's words, as well as on the focus on telling individual stories of particular places, the complex relationship to reality and authenticity merges. As Patricia Hill Collins notes, this rejection of the world outside the hood is deeply entrenched in mainstream society's views of what is “authentically black": “Poor and working-class Black characters were portrayed as the ones who walked, talked, and acted 'Black' and their lack of assimilation of American values justified their incarceration in urban ghettos." According to Forman, the ghetto in Street Literature is both an imaginary marginalized place, but also a place considered “real." Whether or not the authors experienced these places and conditions first hand and no matter how realistic the representations of life in these projects actually is, the trope of authenticity – as tied to notions of the hood, lived experience, and a counter-hegemonic value system - remains consistent. Similar to Kelly's point that rap music is not just about street life but about entertainment and many rap artists have not engaged in criminal behavior, not all Street Literature authors are from working class situations and their books are likewise meant for entertainment. Nevertheless, what is important here is the enunciation of spaces and places that society marginalizes and dismisses as not valuable. It is not coincidental, for example, that Street Literature arose in a time when the conditions of inner cities have deteriorated and yet continue to be ignored by mainstream society.

In this way, the emphasis on the particulars of “hood" becomes even more important. Both a badge of authenticity and individual identity, the extreme locality creates a space where marginalized identities can be expressed and valued within the discursive frameworks of popular black culture as represented both within hip hop culture and the larger media. As a result, both in the actual stories and Street Literatures’ wider commercial system, territory is significant, both as a marker of authenticity and home. When Trinity describes her friend Joyce getting beaten up, she highlights two important territorial factors: first that it was a girl from “112 street" which is not their hood and that it was for sleeping with another woman's man. The possession is key here as territory is both marked by location and socially. Similarly, when Rio becomes the “capo" of the Douglass projects, it divides territory between Rio and Prince's eldest son Truck who gets control of crack houses from 105th and Amsterdam to 112th and Morningside. Again territory becomes part of identity: “The nine-block kingdom that Truck was given produced enough paper to keep everyone happy, but in Truck's warped mind it didn't compare to controlling a city housing project. Truck felt that it was a slight to his honor. A slight that wouldn't soon be forgotten."

Because the worlds are so small, “repping" or representing the hood is an important part of identity. Tiny spaces become significant. Tim Cresswell notes: “Places are fundamental creators of difference. It is possible to be inside a place or outside a place. Outsiders are not to be trusted; insiders know the rules and obey them. The definition of insider or outsider is more than a locational marker… An outsider is not just someone literally from another location but someone who is existentially removed from the milieu of 'our' place - someone who doesn't know the rules." In Street Literature, people knows their place, whether within their hood, or in relation to the outside world. Those who try to reach too far generally meet sad fates, like Trinity, Winter, and the crew of Street Team.

Interestingly, this insider/outsider dynamic also resonates in the editorial business of Street Literature. Like the trend in hip hop music towards artist-owned independent labels, a number of authors have started their own publishing houses, e.g., Teri Wood's Publishing, or Triple Crown Publications, which was started by author Vickie Stringer, also the CEO. Importantly, this Street Literature territory was carved out after their works were first rejected by more mainstream publishers, although today Nikki Turner Presents, for example, is an imprint under One World Ballantine. Similarly, Zane's Strebor Books is distributed by Simon & Schuster. As Keith Negus has show with rap, however, this tension between an independent territory and a major publisher is more subtle than one might expect at first glance: "I have already suggested that the major companies tend to allow rap to be produced at independent companies and production units, using these producers as an often optional and usually elastic repertoire source. This is not to deny the struggles of artists and entrepreneurs for both autonomy from the recognition by the major music companies. However, I am stressing the above point because I think we need to be wary of the increasingly routine rhetoric and romanticization of rap musicians as oppositional rebels 'outside' the corporate systems, or as iconoclasts in revolt against the 'mainstream' – a discourse that has often been imposed upon rap and not necessarily come for the participants within hip hop culture itself."

Thus without romanticizing Street Literature's early marginalization from the world of corporate publishing, or its greater acceptance into the mainstream today, the genre's structure also reveals aspects of its unique spatial logistics. The major names and imprints like Terri Woods, Vicki Stringer, Nikki Turner, and Carl Weber have created their own groups of authors that align themselves with these major names. Thus, in the acknowledgments page of Street Dreams, K'wan recognizes his membership in Stringer's group and Triple Crown while Ashley & JaQuavis thanks Carl Weber for “believing in the 'KIDS' and putting us on." Acknowledgments over and over refer to publishing companies in terms of “families," as older writers mentor, edit, and manage up-and-coming ones. Like the hip hop artists that appear on each other's labels, writers regularly thank a litany of other Street Literature authors from their group.

A Few Conclusions

Although originally based on street marketing and vending, modes of distribution that continue to be current and important aspects of these books' dissemination, like hip hop before it, Street Literature has now expanded to a much wider market. Despite this growth, certain spaces – the most local of specific streets, corners, and housing projects - remain an incredibly powerful and identifying theme. Additionally, this identification with both the ghetto and hood has created a new black cultural expression for inner-city life. It is a world that shuns mainstream understandings of criminality and black sexuality at the same time as it acknowledges common stereotypes. Perhaps this is why Street Literature is both so resonant with many readers and seen as dangerous – as an articulation of both is what is said about these populations, deconstructed and re-imagined in fiction. Forman concludes, “Fundamentally, it is a problem of containment: containment in a spatial and physical sense pertaining to the institution of 'vertical ghettoes' or public housing high-rise structures, or in broader cultural terms, containment as a crisis founded in the inability to sustain the traditional authority of European-based values systems."

Despite Street Literature's many parallels to hip hop in terms of its spatial logistics both in content and development, as novels and not music, this genre also presents even greater opportunities to examine the way space and place is imagined in the inner cities (and as Graaff's recent research suggests, prisons). Both aware of the center and coming from the margins, it is a unique source of insight into self-representation of the ghetto. That many of the worst stereotypes of the black working class are present in Street Literature is not a reason to dismiss the novels but instead suggests a greater need to understand how ghetto and hood as spaces are imagined.

As author Jihad argues, this drive to present another point of view and another story that is of the ghetto, real or imagined, is the unique space that Street Literature is creating creatively and culturally. He writes in an email to this author, “Although there is a negative to Street-lit, I think what far outweighs the violent and negative stories is the fact this genre has done more to combat illiteracy in the last 10 years in the Urban community than anything else by far. Not only are Black men reading but they are writing life as they see it, and as they've lived it… what the suits and the high browers don't see is what these writers, prisoners, and young folks in the hood see everyday. Imagine being dependant on a system that doesn't care about its lowliest class, so much that it allows ignorance to run rampant in rat infested tenements, such us the Claremont project housing development in the Bronx."

The realities of inner cities, drugs, and crime resonate for the authors and consumers of Street Literature in the places and spaces of the novels. Although they may not be the place of all the readers, the specificity, the tightness of the world reaches across cities. It is the common marginalization, the power of the streets that resonates in the imagined world these books portray. As Rio learns, “This was the price you paid when you slept with the streets. She was a jealous bitch who would always find a way to bind you to her." Neither real nor imagined, thirdspace or third-as-othering space is a powerful force in Street Literature, a way of facing the global world through the local that cannot be ignored.

March 2012

From guest contributor Melissa Castillo-Garsow, Yale University

|