There’s a long history of presidents reading books to help them conduct the affairs of state. Teddy Roosevelt was famously shaped by military historian Alfred Thayer Mahan’s The Influence of Sea Power Upon History in pursuing his aggressive naval program and international policy. Richard Neustadt’s political science classic, Presidential Power and the Modern Presidents, was favored reading in both the Kennedy and Nixon administrations. More recently, President Obama consulted Doris Kearns Goodwin’s Team of Rivals, a book about Lincoln’s cabinet during his first term in office.

But now, over two years into his presidency, Obama, and other politicians seeking the White House, might want to move in a more idiosyncratic direction for presidential guidance: they might want to consult a zombie novel or two.

At first glance, this suggestion appears fairly unpromising. Unlike books focused on warfare, political brinksmanship, or dealing with dysfunctional blocs of advisors, zombie literature has a dirty secret: the undead don’t exist. So why should the Chief Executive read about reanimated corpses when so many real problems – economic instability, mounting federal and state debt, and global warming (to name just a few) - demand our attention?

One answer: zombies are stand-ins, proxies for more familiar problems in our everyday lives. For example, in "My Zombie, Myself: Why Modern Life Feels Rather Undead," New York Times writer Chuck Klosterman accounts for America’s current preoccupation with zombies by contending that dispatching zombies is “philosophically similar to reading and deleting 400 work e-mails on a Monday morning or filling out paperwork that only generates more paperwork, or following Twitter gossip out of obligation." As opposed to the more intimate and personal menace posed by other macabre figures such as vampires, zombies are distinguished by their fungibility and scale. In this way, eradicating the wash of information crawling across our televisions, computer screens, and synced appointment calendars is a lot like dealing with reanimated armies.

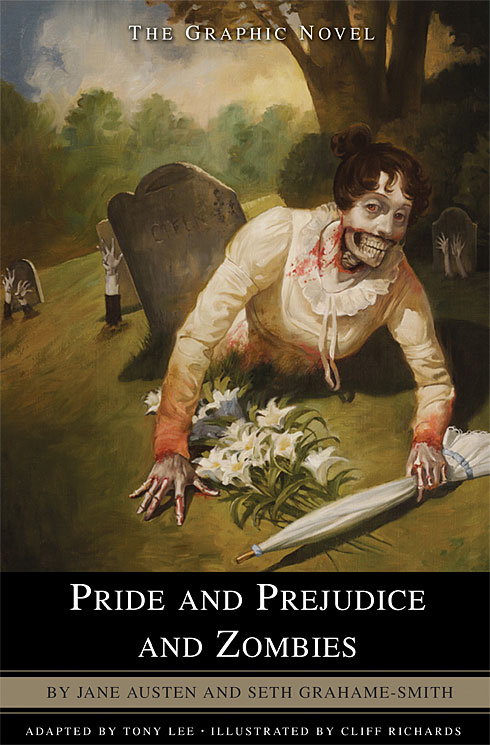

Besides viewing zombies as surrogates for the mind-numbing distractions of modern life, they also retain features of more pointed threats. Zombies are diffuse (no central leader or figure directs their movements), mindless, and ubiquitous. They insinuate themselves into a range of settings from Seth Grahame-Smith’s nineteenth century ballrooms (in Pride and Prejudice and Zombies) to filmmaker George Romero’s farmhouses and shopping malls. In these ways, zombies bring to mind the decentralized, pervasive threat posed by contemporary terrorist cells.

In addition to reminding us of terrorists, the signature features of zombies also suggest runaway diseases. Today’s fear of illness include recent outbreaks such as the H1N1 virus, the largely untreatable enterohaemorrhagic strain of E. coli (described in Spiegel Online as “a totally new disease pattern" whose Shiga toxin attacks the brain), and aggressive new strains of wheat rust diseases that are destroying crops throughout the globe. These bacteria and viruses, as well as the walking dead, are essentially programmed to kill. As Dr. Millard Rausch puts it in describing zombies in Romero’s Dawn of the Dead (1978), “these creatures are nothing but pure, motorized instinct." Contagions and zombies alike bear no malice towards their victims, replicate rapidly, and generally require only human tissue to sustain themselves.

So there are good reasons for reading our current cultural absorption with the “zombie menace" as a stand-in for our worries about very real dangers facing the nation and globe. Indeed, the Center for Disease Control recently seized on the popularity of the zombie trope to disseminate "Preparedness 101: Zombie Apocalypse," an internet based guide for surviving a “scenario" in which “zombies would take over entire countries, roaming city streets eating anything living that got in their way."

The CDC’s point is not to give “credence to the idea that a zombie apocalypse could happen" but to suggest that the same kind of planning that would go into dealing with such a fictional cataclysm would be pertinent for dealing with real emergencies. The message seems to be: whatever future crisis we face, your government has a plan in place for dealing with it, and the will, expertise, and resources to save you.

But the CDC’s zombie conceit is inadvertently revealing in another way. It underscores the curious status of politics and government in the zombie oeuvre. Almost all zombie works are apocalyptic not dystopian – they take place in a context where the political order has collapsed or is in full retreat, not where it is a reigning but malevolent force. As the radio announcer in Romero’s genre defining film Night of the Living Dead intones, “military personnel and law enforcement agencies have been working hard in an attempt to gain some kind of control of this situation, but most of their efforts have been marginally futile."

The chaos represented by the unimpeded presence of the walking dead connotes a breakdown of the rule of law and the protection from private violence that the state is supposed to ensure. As the sociologist Max Weber put it, governments are distinguished by their ability to exercise “a monopoly of the legitimate use of violence." But in a zombie-riddled world, violence is omnipresent and the government’s monopoly long gone. Similarly, zombie films, television shows, and lit depict a world in which another classic function of government, determining “who gets what, when, and how" is undermined or impossible.

But here’s where government officials, and the rest of us, get an unexpected payoff from consuming and thinking about the numerous zombie works on our current cultural scene. In suggesting the limits of some of the traditional functions of government, “zombie lit" invites us to consider what else government can and should do for its citizens. Given America’s arguably fading status as a hegemonic state on the world scene, and the challenges our indebted nation faces in distributing scare resources to its citizens, the times are ripe for rethinking the distinctive roles and contributions of politics and politicians. And, again, on this question, recent works about zombies provide an implicit answer: government has a unique role to play in information management.

As suggested earlier, zombie invasions can be read as a metaphor for data invasion. Modern life is beset with bytes, figures, words, and images competing for our attention and flowing at us from all directions. Some of this information can undoubtedly make us smarter, but taken all at once, it can also make us function poorly. As George Eliot warned over a century ago, “If we had a keen vision and feeling of all ordinary human life, it would be like hearing the grass grow and the squirrel’s heartbeat and we should die of that roar which lies on the other side of stillness."

We need to manage information and quiet its roar. Government can play a unique role in meeting this imperative by both communicating important and accurate information to citizens to help them make good choices, and by coordinating the vast array of data that flows through the channels of the state itself.

In works about zombies, the importance of these twin tasks is depicted in numerous ways. First, and most obviously, governments need (but usually fail) to communicate basic and trustworthy information about how zombies are both propagated and dispatched. In Max Brooks’s novel World War Z, the zombie plague is initially downplayed as a form of “African rabies" and ignorance about how the disease is communicated allows it to spread through family members, influxes of refugees, and even a black market in internal organs. Romero’s film, Dawn of the Dead also underscores the importance of accurate information by opening with a chaotic Philadelphia TV station broadcasting outdated reports on supposed “safe" houses – that have actually been infested with the living dead.

In our own, zombie-free lives, the stakes of having a government as a credible source of information is implicated in everything from cigarette warning labels, to the fight against AIDS (in which the state played an important but decidedly imperfect role in educating about the virus and its transmission), to the evacuation of New Orleans during Hurricane Katrina (when Mayor Ray Nagin was criticized for waiting so long to send out his emergency evacuation order).

In addition to speaking clearly and reliably to its citizens, the contemporary state needs to manage and coordinate its own sources of information. Again, in the case of Katrina, FEMA director Mike Brown was criticized for having worse sources of reporting than private journalists. Gathering and processing information is also vital in the context of today’s military and intelligence decisions. After the September 11 terrorism strikes on New York and Washington, it became clear that a surplus of information as much as a deficiency contributed to our failure to anticipate the attacks. In the same vein, New York Times reporters Thom Shanker and Matt Richtel have explained that data is a potent weapon in the 21st century: “Unprecedented amounts of raw information help the military determine what targets to hit and what to avoid." That said, military officials are sometimes “drowning" in this information, and the contemporary military “faces a balancing act: how to help soldiers exploit masses of data without succumbing to overload."

In zombie films and lit, the government’s own inability to identify and use facts effectively is often a crucial plot element. In the film 28 Weeks Later, soldiers attempt to destroy two children whose blood holds the key to eliminating the zombie-producing “rage virus," because they mistakenly believe them to be infected. In Brooks’s World War Z, an early battle between the U.S. military and millions of undead streaming from the five boroughs of New York City turns on the failure of the government to ascertain basic needs such as how much ammunition is required to stem the endless flow of “Zack."

But this so-called “Battle of Yonkers" is also a calamity because of the information “overload" experienced by human warriors linked to a “Land Warrior combat integration system." Through this technology, soldiers can use video cameras on their colleagues’ weapons “to see what’s over a hedge or around a corner." But the system also allows fear and misinformation to spread between the troops. As one soldier concludes, “panic’s even more infectious than the Z Germ and the wonders of Land Warrior allowed that germ to become airborne." In the fictional Battle of Yonkers, U.S. military intelligence and information processing problems result in a “catastrophic failure of the modern military" and implicitly warn of similar debacles in our own data-soaked defense apparatus.

In his recent chronicle of the evolution of life on our planet, Here on Earth, the scientist Tim Flannery concludes that for all of humanity's technical marvels, "it's not so much our technology, but what we believe, that will determine our fate." We might extend Flannery's statement to note that in our new century what we believe (and what ideas we make priorities) will be influenced by a maelstrom of new information sources and a competition for the hearts, minds, and inboxes of our citizens. Meeting our national and global challenges will require information that can be reliably shared, used, and trusted by private citizens and public officials alike. Seen in this light, consuming works about zombies is useful in suggesting the limits of government power and planning while also pointing to pressing political imperatives in the brave new age of data.

October 2011

From guest contributor Bruce Peabody, professor and former chair of the Department of Social Science and History at Fairleigh Dickinson University

|