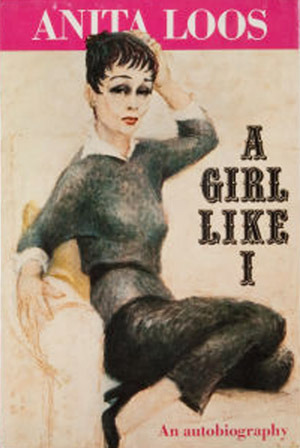

Raised on fairy tales, I was taught to be good, quiet, and pretty. If I cultivated those characteristics, then I would be rewarded with a fairy godmother and a prince who would give me beautiful things and take me away from chores to live in a palace. But that lesson encourages a passive woman, a passive approach to life. I needed to act. I felt called and driven to act. Acting women are not quiet, and they may not always be good. In fact, they probably say outrageous things. Statements intended to provoke and shock. Early Hollywood screenwriter Anita Loos was certainly one of these women as evidenced in her autobiography A Girl Like I. While by no means a “tell-all," the memoir nevertheless titillates.

One of her most shocking admissions comes early on in the book. She explains that her father came to Northern California in search of gold. A shyster asked for money up front to lead her ancestor to the best location for panning – only to leave him high and dry lost in the woods. Instead of feeling pity for her grandfather, however, she “only felt a lively admiration for the trickster who had put it over on Grandpa." She admits, “It appears that I had inherited a love of larceny from someone in my ancestral line." Throughout her life, her close company remained gamblers, philanderers, and other questionable companions.

Loos very nearly brags about her grandmother Cleopatra’s drug use – comparing her to the mother in Eugene O’Neill’s Long Day’s Journey Into Night. Speculating the addiction was linked to morphine or cocaine, Loos recounts a visit almost glamorized – even romanticized – in its description: “By the time we grandchildren made our appearance on the scene, Grandma had become a recluse in a darkened bedroom, where our visits were dramatized as special occasions and were fraught with mystery. We could hardly see her in the dim light, but her ailment, whatever it was, only made Grandma look romantic. Dressed in a pale blue wrapper with a wide cape of eyelit embroidery, she reclined on a divan of Burgundy red velvet. As a coverlet there was a crocheted throw, in the fashioning of which Grandma certainly had no part, for her helpless white hands could never cope with a crochet hook. Her still youthfully brown hair, draped over her ears and confined in a low bun, made her face seem very pale by contrast. On kissing Grandma, we got a delicious whiff of lavender from a cologne called Florida Water, after which we exchanged some brief amenities, were treated to a few jelly beans and dismissed, feeling that we had made a detour into far off territory." For Loos, swindling and drug addiction paralleled drama and excitement – and those characteristics were not only interesting to her, they were admired.

Grandpa and grandma had a lively daughter, Nina, who hooked a “high-powered international confidence man named Horace Robinson" after she was sent off to boarding school. Loos explains, “Bad behavior got Nina a lot farther than it ever got her mamma, for she finally escaped from the valley." The author goes on to write, “Nina fell in love with him at sight; but the reason he is important to this story is that, at the age of seven, I was to do exactly as Nina did, and I think Horace Robinson may have set a pattern for all the men who would ever fascinate me." Here Loos introduces her attraction to neglectful and abusive scamps, men not unlike Robinson and her own father.

Later in life, Anita and her family settled in San Francisco where Loos recounts her father’s myriad affairs, his absences, his drinking binges, as well as his inability to keep food on the table. In one anecdote, she describes her time with pop exploring the tenderloin district of the Barbary Coast “a dazzling area of cafes, gambling spots, honkytonks, and places for more lusty diversion." She goes on to recount one theater’s performances: “the only spot that featured ‘legitimate’ acting was a tiny theater where the drawing-room comedies of Sir Arthur Wing Pinero were acted quite earnestly except that the performers didn’t wear any clothes. So the eminent old thespian [David Warfield] may have been trained in that naughty troupe." Even as a child, Loos marveled at the underworld to which her father introduced her.

Loos likewise spins tales around the infidelities of her father. “My Pop’s exciting girl friends," she writes, “must have caused Mother many hours of suffering." Loos expounds: “I was first to hear about them one afternoon when a strange young lady showed up at the house to pay a call on Mother…It appeared that she had come with a plea for my mother to get an immediate divorce and let her have R. Beers for keeps. But instead of treating the beauty with disdain, my mother was actually sympathetic. She explained that she had suffered for years because of other women’s infatuation with her Harry, and that it would be best for the young lady to be assured of his feelings before trying to legalize her penchant for him." Loos then discloses the girl’s reaction to Mother, “The beauty, who had prepared herself for a big dramatic scene, was so let down by Mother’s composure that she couldn’t find adequate dialogue for it. She departed and presumably went the way of all young creatures who threatened to disrupt our home." Loos actually sympathizes with her father after she learns the truth about his dalliances and prolonged absences – she asks, “How could he be blamed because fascinating ladies fell in love with him?" The author even wonders “how anyone so lacking in spirit as [her] mother had ever managed to hook [her] scintillating Pop." Her admiration always sides with the scoundrels of life.

After Loos won a competition for an F.P.C. Wax ad written in verse, her father “borrowed" the five dollar prize and offered her interest of ten cents a week. Of course, Loos was never to receive any money from good ol’ pop. She reflects, “When that 10 per cent finally amounted to more than the loan, I told Pop to forget about the capital and just come through with the interest. But I was only kidding; I never expected to get my money back and would even have felt let down had Pop returned it. Although unaware, I was beginning to sense the thrill a girl can feel handing money to a man." Her relationship to her future husband would involve just this dynamic.

Mining her life for the most shocking stories and telling them to her fans in A Girl Like I, Loos replicated her lifelong desire to stand out. A story she tells from her childhood underscores the decisions she made in terms of the structure and organization of her autobiography. She was petite all her life – and for some years matched the size of her sister Gladys. Her mother would dress them up in matching clothes and parade them down the street as blonde and brunette twins. This action would bring them a lot of attention. When Gladys died at only eight years of age, Mother rued, “People won’t look at us anymore, honeybunch. Now we’ll be like everybody else." Loos remembers, “My own sardonic reaction was to think: I’ll have to find some way to overcome that." Becoming a world famous screenwriter at the dawn of Hollywood and penning the bestselling novel Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, which has been adapted for stage and screen in many incarnations, certainly accomplished that. The reader still remains startled, however, at her selfish response to her sister’s death.

Her lack of sensitivity for a certain underclass of women likewise shocks. After discussing her visits to her doctor brother Clifford’s clinics, she ruminates, “It was in my brother’s office that I had my first encounter with ladies of the evening and decided that the real truth about them was not that they possessed ‘hearts of gold’ described in fiction but that they had heads of bone. Their traditional generosity came from stupid wastefulness, and they were, almost without exception, morons." Loos continues, “Those San Diego ladies of the evening may have given me a slant on that timeworn profession which I was to capitalize on when I wrote Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. For I couldn’t take seriously the lost virtue of a heroine who was too dense to have any kind of emotional experience at all." Published in 1966, Loos’s autobiography reveals an astounding insensitivity to those who may have come from underprivileged backgrounds and sought to survive or to those who may not have been blessed with as high an IQ as the author. Loos may have had one of her first scenarios produced by D.W. Griffith, starring Mary Pickford, yet she had no sympathy for those who were less fortunate at her brother’s practice.

Loos soon married her director-partner, John Emerson, yet discusses his philandering with such a matter-of-fact glibness – the tone, in itself, startles the reader. For example, in one passage she proclaims that John decided he would have Tuesday nights off as a husband, do as he pleased, only to re-appear on Wednesday, with no questions at all to be asked by Loos. She accepted this condition and began to throw “cat parties" with the other “Tuesday widows," never calling for divorce as many other women might have.

She even pulled a fast one on poet Vachel Lindsay, developing into “a small female Cyrano de Bergerac." In her own handwriting, actress Mae Marsh copied out Loos’s letters. It wasn’t long before Lindsey fell for the ruse, proclaiming his passions for Marsh. Of course, all fell apart once he actually met Marsh in New York, and he switched his affections to Loos the Intellectual instead. The screenwriter never told him the truth about Mae’s letters, however; the deception continued to stand.

As a screenwriter for D.W. Griffith, the Talmadge sisters, Douglas Fairbanks, and the boy wonder of MGM Irving Thalberg himself, Anita Loos showed the world she knew very well how to get and keep attention. The shocking anecdotes she chooses to relate in her autobiography further underscore her skill at being remembered and remaining relevant even into the 1960s. While her book is free from the traditional shock of Hollywood memoirs – reveling in the author’s sexual affairs or various personal addictions – Loos’s book, nonetheless, displays her keen writer’s “ear" in terms of knowing just where to turn her spotlight of a pen to keep her reader’s prurient interest intact.

February 2017

From Leslie Kreiner Wilson, Pepperdine University |