The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences is no stranger to controversy. Some of cinema's greatest films and filmmakers either did not win the top Academy Award (Best Picture, Best Director), or they were ignored entirely. In this regard, the lack of Oscar recognition, in 1989, for Spike Lee's Do the Right Thing (DRT), does not make it unique. However, the year's two most prominent winners, Driving Miss Daisy (DMD) and Born on the Fourth of July (BFJ), suggest failure to recognize Lee's film goes beyond mere oversight, revealing a more deep-seated racism, rooted in fear of minority America. DRT was not the first film directed by an African-American filmmaker to deal with issues of contemporaneous oppressive, institutional racism. However, it was unique in that it was a mainstream studio production, dealing with racial issues, told from a black perspective, and refusing to conform to established Hollywood narrative norms. DRT is, today, widely regarded as one of the most creatively and culturally important films ever produced in the United States. An analysis of the film's narrative discourse, interwoven with discussions of Hollywood's historical handling of social justice themed films, will reveal that the failure to recognize the film represented a rebuke of the film's message, its creator, and its overall aesthetic. Finally, a formal and thematic comparison to DMD and BFJ will reinforce this argument.

Spike Lee wastes no time establishing the importance of music to the narrative discourse of DRT. Alternately, diegetic and non-diegetic, conventional and innovative, old and new, Lee uses the clash of jazz and hip-hop as a foundation for the film's narrational mode and visual aesthetic. Music functions, at times, as a unifying agent and, at others, as a means of establishing individual and collective identity. The more traditional use of jazz creates a sentimental, plaintive mood that is frequently unsettled by the rhythmic power of hip-hop, specifically, Public Enemy's "Fight the Power," a song that literally becomes a narrative agent. The interplay of these two musical genres inform the film's visual style, interweaving with and becoming central to its discourse, positioning the film in the modal history of Hollywood cinema (jazz) while simultaneously announcing a distinct narrational and aesthetic departure (hip-hop); a departure, for which, Oscar voters were not prepared, thus did not condone.

Jazz is the first auditory or visual element presented to the viewer in DRT. A plaintive saxophone plays against a blank screen before the inevitable appearance of the Universal logo (the film's distribution studio). As the saxophone continues to play, Lee's production company is revealed, followed by the film's title. The use of jazz in this brief, opening sequence communicates music's centrality to the narrative discourse, establishing the more traditional, non-diegetic, mournful half of the film's score, something Victoria E. Johnson refers to as "historic-nostalgic." Beginning a film with a musical (often jazz, or romantic) accompaniment to opening credits was and is very common Hollywood practice and, in this case, functions to settle the spectator into a false sense of security. By opening the film in this manner, Lee knowingly cues the spectator to expect a more traditional, mainstream film, an expectation that will be shattered almost immediately. Functioning primarily as non-diegetic background music, jazz frequently accompanies and facilitates character introductions and interactions, as in the case of two of the neighborhood's elderly characters, Mother Sister (Ruby Dee) and Da Mayor (Ossie Davis). Introducing jazz as a nostalgia signifier prior to the entrance of "Fight the Power," immediately establishes one of the film's primary thematic concerns: the clash of the old and the new.

Underscoring this thematic clash is the order in which the film's respective distribution and production company logos are revealed. Consistent with its status as the film's distributor, Universal's logo is the first image presented to the viewer. Presenting Universal's logo first is not only established Hollywood protocol, it is an initial, tacit indication of a broader institutional power structure; one that Public Enemy, and by extension, Spike Lee, will spend the duration of the film imploring the spectator to fight. The justification for this reading lies in the subsequent presentation of Lee's production company logo, 40 Acres and a Mule Filmworks, a name derived from a Reconstruction era order, that was “…the first systematic attempt to provide a form of reparations to newly freed slaves...” (Gates, “The Truth behind ‘Forty Acres and a Mule’”). The placement of Lee’s logo further establishes not only the old vs. new dichotomy so prevalent in the film, but also couches institutional divisions in racial terms; Universal, representing mainstream, white America, and 40 Acres and a Mule Filmworks, minority, non-white America. Lee acknowledges the established studio hierarchy, on the one hand, and firmly takes responsibility for the film and its content, on the other; a modernist aesthetic that is cemented by the next frame, beginning with the words “A Spike Lee Joint”. Through the juxtaposition of these images, DRT acknowledges Hollywood’s history of using white voices to tell black stories, and declares that the author of this story will not be white; a clear challenge to institutional Hollywood, and by extension, Oscar voters.

Following the jazz infused introduction, the opening bars of Public Enemy’s “Fight the Power” rush in, taking over the narrative space, and cementing the clash of old and new, jazz and hip-hop. Drawing from music video traditions, a series of jump cuts, edited to the beat of the song, reveal Tina (Rosie Perez), bathed in red light, against a backdrop of brownstone apartments in the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn. As the song plays in its entirety, Tina proceeds to feverishly dance, center-framed, in front of the backdrop, frequently addressing the camera directly, acknowledging the spectator in the process. Although this sequence is not related to the film's story, it is vital to establishing the film's narrational mode and visual aesthetic. Like the opening lines of Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet wherein the story's conflict and setting are established prior to the revelation of any characters, the song's lyrics provide important narrative information, establishing the season and year (summer 1989) and the film's central struggle ("Our freedom of speech is freedom or death/ We've got to fight the powers that be"). The use of the music video aesthetic blurs the line between diegetic and non-diegetic music, firmly establishing not only the role of music, but its structural function in the film's discourse, as well. The rhythmic editing is done to the beat of the music, and stylized images dominate the visual aesthetic, introducing Lee's preferred mise-en-scene: canted angles, wide angle close-ups and highly altered color representation (specifically, red). Not only is Tina dancing to the music, she is, at times, acting out the lyrics, such as when she dons a boxing outfit to visually articulate the word "fight." Tina's actions melt into the lyrics and rhythm of the music, underscoring the narrative discourse of the film while establishing the importance of this specific musical genre, which at the time was relatively new. As Victoria V. Johnson states, this marriage of sound to image "is extremely significant for its foregrounding of an immediate, equivalent, and co-dependent alliance between the film’s visual image and the musical sound track." All the narrative elements combined in this opening sequence serve to separate DRT formally from most mainstream Hollywood films. This opening challenge to the status quo, establishes the film and its characters as "other," something to approach with caution. From the thematic concerns of hip-hop, which were "characterized by the 'politicized' voice of black, urban males," as Johnson phrases it, to the unsettling and unorthodox canted angles, rhythmic editing, stylized color application, and wide-lens close-ups, everything serves to unsettle those expecting a more traditional film.

This music video-like opening does not just introduce important narrative information, it also blurs the line between fact and fiction. Tina's direct address, modern, hip-hop inspired dance, coupled with the "Fight the Power" lyrics, drag the spectator from the real world into the narrative one, suggesting the events in one, inform the other. Public Enemy (Chuck D, specifically) are pulling no punches when they say:

Elvis was a hero to most

But he never meant shit to me you see

Straight up racist that sucker was

Simple and plain

Mother f--- him and John Wayne

Because I’m black and I'm proud

As Tina dances, looking directly at the camera, she is daring the spectator to deal with the enormity of these lyrics. The relative safety of the voyeuristic-like position usually available to spectators, vanishes once the actor acknowledges the camera's presence. Spike Lee, through Tina's gaze is saying, "You see me, but I see you," further obfuscating the line between author and spectator. The jazz score of the opening few moments is gone; there is nowhere for the spectator to hide. Furthermore, calling Elvis, and through association, John Wayne (two of Hollywood's biggest stars) racist, Public Enemy is indicting institutional Hollywood, at large. Moreover, one of Elvis's lasting legacies, is his appropriation of African-American music, and his subsequent contribution to the development of the music video form. Lee returns the favor by adopting a music video-like opening to accuse Elvis, and the historical institution he represents, of racism. Spike Lee, in much the same manner as the opening presentation of the production studio logos, is acknowledging the past and charting a path to a different future.

A final note regarding the role of music in this opening sequence and the formal aesthetic it inspires: Lee deals with the dichotomy of the old and the new throughout his film. They are not always in direct conflict; frequently, they function discursively, creating a dialogue between two alternate modes of action. Jazz, although it is associated with the older generation and traditional Hollywood filmmaking, does not represent mainstream, white America. It is not the music of the antagonist, in other words. Jazz, often, underscores a previous generation's mode of civil action, espoused by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and represented in the film by Da Mayor and Mother Sister. Hip-hop, on the other hand, is tied to the civil action associated with Malcom X and represented predominantly by Radio Raheem (Bill Nunn). The dialogue represented by these musical genres and political figures suggests two alternate approaches to the same issue: institutional racism. Lee seems to be questioning whether the social activist methods espoused by Dr. King and adopted by the previous generation are still valid and appropriate. By associating this generation with jazz (a musical genre whose origins lie in African-American culture and which directly informed hip-hop's formal structure), and by positioning the two musical genres in the same narrative space, Lee is acknowledging its influence on the present.

At the time of the film's release, jazz had been, like rock and roll, largely appropriated by white America (Bill Evans, Chet Baker, Dave Brubeck, et al.). It was familiar to mainstream audiences and did not represent any threat to the established order. Hip-hop, on the other hand, was something new, not yet under the control of institutional America (as it seems to be today). Without belaboring the point, the unfamiliar nature of hip-hop and its prominent role in the film represented a direct threat to the status quo. Given the demographics of Oscar voters at the time, 94% white, with an average age of 63, it is very likely that this unsettling thematic clash of the old and the new, coupled with the correlated threat to the status quo, helped precipitate the ultimate rebuke to the film and its message.

The formal elements introduced in the opening sequence and the subsequent threat they pose to mainstream Hollywood are fully realized in the character Radio Raheem (Bill Nunn), not the film's protagonist (it can be argued that the film has no true protagonist), but he is the film's pivotal character. Raheem is the voice through whom Lee filters his thesis, "Fight the Power," and he serves as something of a prophet for the neighborhood. Dressed in a Bed-Stuy (Bedford-Stuyvesant) T-shirt and prominently wearing two sets of gold brass knuckles, featuring the words "love" and "hate," Radio Raheem travels through the neighborhood spreading the message of "Fight the Power." The song, blasting through his boom box, becomes part of the narrative space, fully diegetic, declaring Radio Raheem's intentions. He is a character of few words, but strong actions, allowing the voice of Public Enemy to speak for him. Raheem becomes inseparable from the song, and together they dominate any environment they encounter. By associating Raheem with hip-hop, Lee positions Raheem as part of a younger generation that is less willing to accept the status quo. As Mark A. Reid states, "Lee is trying to show his audience that many African-Americans are increasingly rejecting Dr. King's nonviolent tactics as a means to achieve social and economic equality in the United States."

The use of direct address, introduced in the opening sequence, is given voice with great specificity through Raheem's delivery of his iconic monologue. Tina's initial shadow boxing-like dance, is narratively actualized by Raheem, staring at the spectator, and throwing jabs at the camera as he delivers his monologue. Explaining the significance of his brass knuckles, Raheem declares that the world is caught in an eternal struggle between love and hate; if he loves you, then he is there for you, but beware if he hates you. Raheem's fists pause in front of the camera as he explains the meaning of each set of knuckles. The wide-lens exaggerates the size of the knuckles, covering Raheem's face, shifting the focus from the individual to the associated action. The music playing in the background allied to the full-framed depiction of the knuckles, suggests that Raheem is speaking for his neighborhood and his generation, again reminding the spectator of the clash between the old and the new. Where the previous generation dealt with social justice in one way, he is proposing a new approach (albeit, one that was presented in the previous generation, as well). Raheem's speech seems to be in line with only one of the two quotes appearing in the film's conclusion. The first quote, attributed to Dr. King, suggests that violence is counter-productive. The second quote belongs to Malcolm X and refers to his belief in the presence of both good and bad people in America, the bad ones having the power. He goes on to suggest that violence in the form of self-defense, ceases to be violence, and becomes intelligence, instead. The reference to both a power structure and the need to protect one's self lie at the heart of Raheem's speech, declaring that love is not meek, and when attacked by hate, capable of great action. As with Malcolm X, Raheem, and by extension, Lee, is not advocating for violence. However, if attacked by the forces of hate, he and his generation will not hesitate to defend themselves. By directing this monologue at the camera, Lee again blurs the line between author and spectator, reality and fiction. The spectator is forced to deal directly with Raheem and the generation he represents, exacerbating the opening's lingering unsettling effect for those not in line with Raheem's way of thinking. As with the opening sequence, but with greater ferocity and specificity, Lee challenges the spectator to choose sides. Johnson believes, “Rap's association with the youthful Raheem, its aggressive political message, and its capacity to set the entire nationhood at attention (aurally and spatially) imply that his generation of black youth is allied with change." Judging by the film's critical reception and lack of Oscar recognition, it is clear what side most spectators chose.

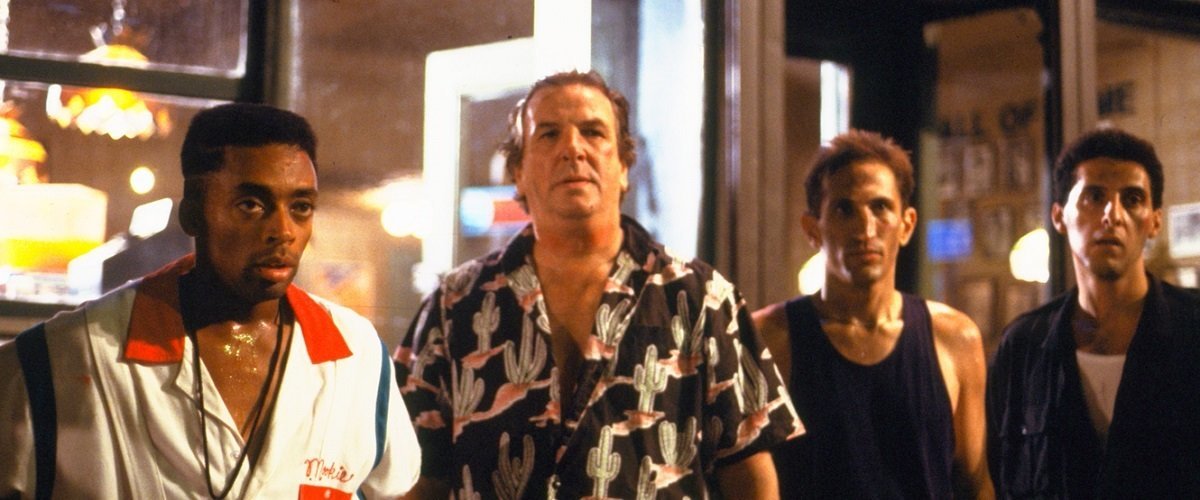

Radio Raheem's pivotal status within the film is realized in the film's climactic scene. Raheem becomes the catalyst for the destruction of Sal's Famous Pizzeria, an event that can only be described as the narrative manifestation of Public Enemy's lyrics. Raheem, Smiley (Roger Guenveur Smith) and Buggin Out (Giancarlo Esposito), enter Sal's, Public Enemy at full blast, and demand recognition in the form of the inclusion of African Americans on Sal's "Wall of Fame." Sal ignores their demands, instead ordering Raheem to turn down his music; something he has no intention of doing. Sal quickly resorts to the use of racial epithets and, attempting to wrest control of the situation, proceeds to destroy Raheem's radio. The consequences prove fatal for Raheem as, true to his word, he retaliates, resulting in police intervention. A final, tragic moment, eerily recalling current events, results in the police choking Raheem to death. Wide-lens close-ups, canted angles, and blaring music heighten the tension throughout the scene creating an overwhelming sense of chaos that is borne out by the subsequent destruction of Sal's. Raheem openly challenges institutional America as represented by Sal (Danny Aiello) and pays the ultimate price for it. Raheem's "love" and "hate" monologue proves prophetic, as members of his neighborhood and generation exact revenge on the institution that is Sal's. According to Paula J. Massood, Raheem's death and the literal firestorm it ignites "points to the tensions and anger generated by [societal] conditions and its concluding riot touches upon the fear of racial violence repressed at the core of American culture throughout the twentieth century." His refusal to turn down his radio is his and his generation's refusal to be silenced. The spectator's reaction to this scene is likely predictive of their overall reaction to the film. To blame Raheem for disturbing the peace in Sal's is to blame Raheem for his own death and denies the validity of this new generation's voice. Again, blurring the line between truth and fiction, Lee's articulation of Raheem's death intentionally reflects a real-life situation. The police strangle Raheem in a choke hold, which Lee referred to as the "'Michael Stewart choke hold' alluding to the 1983 death of a graffiti artist while in police custody."

Radio Raheem's death brings the implication of the spectator full circle. If the spectator sympathizes with Raheem's monologue, they likely blame institutional power, as represented by Sal's and the police for Raheem’s death. If, on the other hand, the spectator is not sympathetic and has issues with much of the film's discourse (old vs. new, mainstream Hollywood vs. emerging minority artist, etc.), they likely see Raheem as culpable in his own death. David Denby, writing for New York magazine accused Lee of "creating a dramatic structure that primes black people to cheer the explosion as an act of revenge." This opinion likely reflected mainstream, white America's common reaction to the scene and film. Rather than focus on the unjust murder of Raheem, Denby chose to focus on the subsequent destruction of property, a sentiment that resonates to the present day.

To further illustrate how DRT's formal structure functioned to unsettle and alienate many Oscar voters through its denouncement of mainstream Hollywood's involvement in America's wider system of institutional racism, it is important to discuss Sal's Famous Pizzeria and its "Wall of Fame." Sal's Famous Pizzeria is owned and operated by Sal and his sons who are Italian Americans. They profit from local patronage, meaning their income is generated from the neighborhood, which is mostly African American. One of the restaurant's walls features great Italian American athletes and film stars, such as Robert DeNiro and Al Pacino. As Sal is the business's proprietor, he feels it is his right to only include Italian Americans on the "Wall of Fame." Buggin Out, however, does not see things that way and, speaking for a generation, demands Sal include some prominent African Americans on the wall. This basic dilemma speaks to both the genesis of the film's tragic climax and to the oppressive nature of systemic racism. Sal owns the pizzeria; thus, it is a private business. However, for his business to be profitable, he must rely on the local population. When he has customers in his pizzeria, the establishment becomes a hybrid private-public space. It is private in the sense that Sal is still the owner, but it is public in that it is a gathering space for the local community who pay to be there. As such, Buggin Out is simply requesting to be acknowledged for his role in helping Sal's be a successful business. He does not demand that Sal remove all Italian Americans in favor of African Americans; he simply wants recognition and inclusion, something that institutional America has largely denied African Americans throughout the nation's history. Sal's refusal to include any African Americans on the wall indicates his unwillingness to recognize the vital role the local population plays in his successful business. The wall is symbolic of the wider exclusion of African Americans from the power structures of America. African Americans contribute to the profits of the powerful, but are excluded from the ownership positions that would enable them to profit as well, forever reinforcing the status quo. According to W.J.T. Mitchell, the exclusion of any African American presence on the "Wall of Fame" recalls other "public spaces in which black athletes and entertainers appear, rarely owned by Blacks themselves." Buggin Out's demand for the inclusion of an African American presence symbolizes an unwillingness to accept the status quo; he is demanding recognition for his patronage. Sal's initial refusal indirectly leads to Radio Raheem's death as, when he arrives at Sal's with Buggin Out, Raheem joins him in his demand to be recognized. Sal's refusal and subsequent destruction of Raheem's radio signifies his belief that his rights as a property owner supersede any rights Raheem may have, including his right to live. Given that the police attack Raheem and not Sal, clearly they align themselves with Sal, reinforcing the oppressive nature of America's institutions.

Following the destruction of Raheem's radio, music, for virtually the first time in the film, is noticeable for its absence. This relative silence heightens both the chaos and severity of the subsequent destruction of Sal's and its "Wall of Fame." The lack of music reinforces institutional America's attempt to silence a generation that refuses to play by the established rules. Sitting behind an angry crowd, Lee, the film's author and Mookie, his character, become inseparable. Sensing the need for action, Mookie directs his anger not at Sal or his sons, but at their property. Throwing a garbage can through the store's front window, Lee sets in motion the fateful riot that destroys the pizzeria. As the can smashes through the window, the image is repeated twice, recalling the music video-like editing in the film's first sequence, suggesting Lee's acceptance of and readiness to "Fight the Power." The fact that Lee directs his anger towards the institution (Sal's) and not the individual is a clear refutation of the widespread critical claim that his film was being irresponsibly provocative. Mitchell states, "Spike Lee himself does the right thing in this moment by breaking the illusion of cinematic realism, and intervening as the director of his own work of public art, taking personal responsibility for the decision to portray and perform a public act of violence against private property." As the crowd proceeds to destroy the exploitative institution that is Sal's, Smiley enters and in the place of the burning photographs, places one he has been carrying throughout the film, featuring Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr., the implication being that a new generation has arrived and, one way or another, it will be recognized.

There is some ambiguity to this final image. However, a likely interpretation directly implicates mainstream Hollywood's involvement in the historic oppression of African Americans. The burning images recall institutional Hollywood past and (then) present, forcing the spectator to acknowledge real world examples of Hollywood's power structure. Furthermore, the fact the photographs are burning in Sal's, an institution whose existence depends on the participation of the local, African-American community, draws attention to the disregarded, yet vital role African Americans play in the success of America's institutions, at large. Lee is declaring the arrival of a new voice and new generation that refuses to be silenced.

DRT held up a mirror to mainstream Hollywood, and institutional America, and they did not like the reflection. Lee's unorthodox mode of narrative discourse served to unsettle many spectators, likely belonging to mainstream America. Most importantly, though, the implication that institutional America derives its authority from exploitation and hate of the oppressed was likely the metaphorical straw breaking the camel's back. Lee's undeniable authorial voice in the film, provided disapproving spectators with an obvious target. Like Sal destroying Raheem's radio, Oscar voters elected to silence Lee's voice through the refusal to nominate the film in the two most prominent categories. Furthermore, the respective winners in these categories (DMD and BFJ) suggest the Academy's desire to not only silence Lee, but to rebuke him and his anti-establishment message.

DMD, the story of the titular, elderly Jewish woman (Jessica Tandy) and her humble, kind, black chauffeur, Hoke (Morgan Freeman), provided Oscar voters with an easy alternative to DRT. In almost every way, the two films are different. Where DRT challenges the status quo, DMD roundly affirms it; where DRT calls for collective action, DMD focuses on interpersonal relationships. Both films, on the surface, deal with racial issues, however, a closer analysis of the stark differences will help explain the Academy's embrace of one and rejection of the other.

DMD follows in a long line of racially themed, Best Picture nominated or winning Hollywood films such as To Kill a Mockingbird (1962), Mississippi Burning (1988), and The Color Purple (1985), wherein the story is set in the past. Setting films with sensitive subject matters in the past dilutes the film's relevance to the present. In the case of DMD, the film begins in Atlanta, Georgia, in 1948, prior to the Civil Rights Movement, and ends in 1973, after the end of the movement. Using the Civil Rights Movement as a backdrop for the interpersonal relationship of Hoke and Daisy not only removes the spectator from the present day, but suggests the reconciliation that occurs in the film's conclusion is reflected in society as well. The civil rights era setting allows the film to acknowledge the existence of a problem, but the focus on an interpersonal relationship between two elderly people, displaces institutional responsibility, shifting it to the individual, suggesting that if everyone just gets along, things will be alright. For Stephanie Greco Larson, "The system is absolved by the idea that if blacks and whites get to know each other, the problems of prejudice will disappear." Furthermore, the period coupled with the age of the protagonists serves as double displacement: racism is not only a thing of the past, but even then, it was simply the remnants of a bygone era. Larson states, "there is no need to blame yourself or your government for the status of blacks."

Another major difference setting DMD apart from DRT is the character of Hoke, who does not seem to have any identity outside of being Daisy's chauffeur. It is as though he has no need for a community of his own and simply exists to aid in Daisy's enlightenment. Hoke is never seen apart from Daisy, and whereas the film shows several members of Daisy's social circle and family, it does not offer any glimpses into Hoke's personal life. The filmmakers were not concerned, apparently, with depicting Hoke as a three-dimensional character. Any pleasure and satisfaction he needs, is derived from the simple act of serving Daisy. Like the film's setting, Hoke's lack of a cultural identity reinforces a Hollywood convention, wherein the non-white characters are virtually without race, existing simply for the needs of the white character.

The most racially insensitive aspect of Hoke's character, though, is its propagation of Hollywood's tradition of casting African Americans as black subservient stereotypes. As Larson argues, American literature, drama and cinema has a long history of casting black characters only as negative stereotypes, "showing them as subservient, hypersexualized, dangerous, or incomplete." Hoke's character is an example of the Tom stereotype which Donald Bogle describes as "socially acceptable Good Negro characters…[who] keep the faith, never turn against their white massas, and remain hearty, submissive, stoic, generous, and oh-so-very kind." The implementation of this stereotype in the Hoke character is offensive for obvious reasons and interweaves, insidiously, with his apparent lack of need for a personal community.

DMD, more than anything, is a civil rights era story filtered through the perspective of white characters, created by white artists and couched in humor. Despite what may have been initial good intentions, it succeeds in displacing the very real, historic, and contemporaneous consequences of both individual and institutional racism. As Helene Vann and Jane Caputi explain, "in many other Hollywood productions, racism and sexism are not presented brutally, but are couched in the standard conventions of humor." This displacement provided Oscar voters, disapproving of Lee’s film, a safe space in which to sentimentalize the conclusion of a struggle that never truly ended and in the process allowed them to dismiss what they considered sensationalized, irresponsible depictions of institutional racism in DRT. According to Larson, DMD's narrative "tell[s] white viewers 'there is no need to blame yourself or your government for the status of blacks because it is either due to problems with the race as a whole, or with individuals.'"

DMD’s Best Picture Oscar victory may not conclusively indicate the Academy's unwillingness to recognize DRT. After all, this would not be the first instance where the verdicts of history and the Oscars diverge. Citizen Kane, 2001: A Space Odyssey, and Vertigo are three of the more prominent examples of important films that did not win the award. On the other hand, Oliver Stone's victory (his third) in the Best Director category for BFJ, indicates a more direct correlation between Lee's film, and its subsequent exclusion from the most prominent awards categories. Oliver Stone's film travels similar anti-establishment thematic terrain, often equaling Lee's more overt narrative delivery, and, at times surpassing it. The only explanation for the Academy's inclusion of one film at the expense of the other may be the average Oscar voter's preference for the delivery of anti-establishment narratives and rhetoric to look and be a specific way: white.

BFJ tells the true story of paralyzed, Vietnam war veteran, Ron Kovic (Tom Cruise), who, as a highly patriotic teenager volunteered for the Vietnam war, citing his desire to serve his country. The film follows Ron's journey from patriotic citizen to disillusioned war veteran, and ultimately to anti-war, anti-establishment activist. The film is very deliberate in its depiction of institutional corruption, failure, and incompetence. A lengthy veteran's hospital sequence in the second act is very specific in detailing the government's abhorrent treatment and neglect of those that fought to preserve the power of the very institution that is now failing them. At times, Ron's character feels like a narrative device Stone used to highlight the many failures of the capitalist system, a common theme in his films. Set in the late 1960s and early 1970s, Stone depicts and valorizes many of the subversive, counter-culture movements that seemed to be so prevalent at the time, including the ubiquitous hippies, disaffected war veterans, and most pertinent to the discussion of DRT, Black Panthers. Considering the existing political climate at the time of the film's release (the Reagan-Bush years), depictions of disaffected citizenry aiming their justifiable anger at a corrupt, capitalist government seems highly subversive and would be if not for the film's conclusion. Ron, identified as a charismatic voice for the counter-culture, is given the opportunity to speak at the 1976 Democratic National Convention (DNC), thereby ceasing to be an agent of subversion and becoming part of institutional America. Perhaps the intended reading of this ending is Ron's desire to change the system from within. However, a brief glance at Kovic's biography reveals a reluctance to become part of the system, preferring to remain on the outside, protesting the corruption of institutional America. Stone's decision to end the film with Ron's DNC speech suggests a certain apotheosis, as though in this moment, Kovic's purpose was fulfilled. Instead of concluding the film with the destruction of the corrupt institution, as is the case with DRT, Kovic is presented as becoming part of it and the upbeat ending suggests redemption. Stone may have felt that Kovic embracing the Democratic party platform in a period of Republican governance, was subversive, in and of itself.

American flags are ubiquitous throughout the film. In the early stages, they serve to remind the spectator of Kovic's patriotism; latter, depicted upside down, they suggest a state of emergency in the country that must be interpreted as having been caused by the corrupt governmental system. This symbolism is one of the more nuanced methods Stone uses to point an accusatory finger at the government. Diegetic music also permeates the film, functioning as period verisimilitude, on the one hand, and setting the film's anti-establishment tone, on the other. Folk singers performing various anti-war songs encourage listeners to join in their cause, a narrative device that recalls Lee's use of hip-hop in DRT. The many protests scenes throughout the film allow Stone to be more overt with his sentiments. Chants of the now famous "shut it down, shut it down" accompany the more specific "1,2,3,4, we don't want your f------ war," which are both followed by the very blunt "f--- the police," a chant that is as important for its linguistic specificity as it is for the person chanting: an unnamed Black Panther. Both the ethnicity of the demonstrator and the target of his ire recall Public Enemy's "Fight the Power" blasting from Raheem's radio. The police prove to be a constant nemesis in the film's latter stages when they are shown to be breaking up demonstrations, arresting protesters, subverting counter-culture causes, and committing unprovoked acts of brutality. These images of police brutality are most memorable for the officers' apparent willingness to target and assault paralyzed protestors, another obvious comparison to DRT.

Both DRT and BFJ, deal with characters taking on institutional authority. Where DRT strongly focuses on the power of a united community to confront institutional racism, BFJ focuses on the power of an individual to lead a community in the resistance of government corruption (a narrative device that recalls the mythologizing of the civilizing frontier individual in American westerns). Both films make use of the power of diegetic music to simultaneously aid the narration of the story and serve as a generational unifying agent. In different ways, both films are unequivocal in their assessment of institutional America; where Public Enemy says "Fight the Power," Ron Kovic and others yell "we don't want your f------ war" and "F--- the Police." A scene involving Ron in the veteran's hospital even addresses the central thematic concern of DRT when a physical therapist discusses the oppressive power of institutional America, and why it is important for him and his generation to stand up to that power. The most striking similarity between the two films is their willingness to depict the reality of police brutality, with one significant difference: the police brutality in BFJ is directed towards white victims.

Despite the many similarities between the two films, there are some significant differences (in addition to the one just mentioned). The respective narrative structures and visual aesthetics are very different. Stone's film is much more in line with Hollywood's dominant narrative mode. His film has a clear three act structure, adhering to the narrative conventions of the Hero's Journey. Visually, Stone's film also bends towards the conventional. He prefers the tight framing associated with telephoto lenses and their accompanying shallow depth of field. This technique is obvious in his frequent use of close-ups that also allow him to separate Tom Cruise from his environment, emphasizing the importance of the individual. The editing is also very conventional. Stone organizes his scenes into the traditional Hollywood pattern of master shot, close-up, reverse-shot. Lee, on the other hand, breaks Hollywood, narrative convention in the film's opening sequence and continues to do so throughout the film. Furthermore, his film does not seem to contain a true protagonist, preferring to highlight the actions of the neighborhood's residents, a clear subversion of the valorization of the individual. Lee also prefers wide-angle lenses, particularly in his close-ups. The wide-lenses expand the depth of field and exaggerate the respective character's features, simultaneously exacerbating the difficulty of the situation while communicating the neighborhood's importance to the characters. The most important differences between the two movies, though, which likely explain the Academy's recognition of one and exclusion of the other, specifically deal with race. BFJ is a heroic story about a white man in a white world told by another white man. Heroes and victims, alike, are white and together they struggle for change. Most Oscar voters could likely see something of themselves in Ron Kovic. Furthermore, the film does not advocate for the complete subversion of institutional America; it simply suggests some important changes, reaffirming spectators' belief in the basic righteousness of America's institutions. On the other hand, DRT is a story about black characters in a black neighborhood, exploited by white business interests, victimized and brutalized by white police officers, and told by a notoriously vocal black man. Finally, the endings of the two films could not be more different. Where Ron Kovic returns to institutional America, Spike Lee dedicates his film to the families of victims of police brutality, erasing once and for all, the fictional story, and leaving the spectator with real world examples of the film's dramatic representations, a final rebuke to "the powers that be."

Unfortunately, there is no way to prove conclusively that the failure to recognize DRT was an intentional rebuke to Spike Lee and his film. Doing so would require both the identification of Oscar voters and an admission of guilt. However, the films speak for themselves. Oscar voters, on the one hand, gave the Best Picture Oscar to a film that affirms the traditions of Hollywood, propagates negative stereotypes, and places the specter of racism squarely in the past. On the other hand, BFJ's victory exposes the basic contradictions and correlated racism in the industry. Oscar voters did not have a problem with anti-establishment messages, they apparently only had problems with non-white people delivering those messages. The final insult to Lee was not only the Academy's decision to reward other films in these categories, it was the failure to even nominate Lee in either category. This non-action remains a rebuke to Lee's film and given the significant narrative and stylistic risks the film took, a rebuke to a new black aesthetic as well. History has declared a different set of results, though, as evidenced by DRT's inclusion in the American Film Institute's America's 100 Greatest Movies list, something that cannot be said for the two other films.

August 2018

From guest contributor Micah Stathis |