We would laugh off the idea of Abner Doubleday being responsible for the Civil War. We’re not even likely to indulge claims of the kind as droll and harmless. And yet, there are more grounds for blaming the War Between the States on Doubleday than for crediting him as the inventor of baseball or for even tolerating that assertion as innocuous whimsy. At least the general was at Fort Sumter in South Carolina on the morning of April 12, 1861, was in charge of the Union batteries there, and did give the order to fire the Northern shots in response to the Confederate shelling that has generally been accepted as igniting the hostilities. Later on, he was even a primary figure in the turning point battle of Gettysburg.

The factual evidence ridiculing Doubleday’s connection to baseball, seminal or otherwise, has been established for some time. But the lingering benevolence toward the fatuousness of that connection has reflected another national pastime -- the tentative cultivating of an innocent spirit that has never existed except as fable and that, averting seamier historical alternatives, craves to be accepted at least for the fancy it is; i.e., if children can have their Santa Claus, grown-ups can have their Abner Doubleday. Doubleday as the progenitor of something “purely American" cuts to a profound cultural bias none of its advocates has ever known except as borrowed reverie, but -- for a multitude of social, political, and psychological reasons -- that has been good enough. Purity is never in so much demand as around the suspicion that impurity has been having a very rowdy time.

Few periods in United States history have been rowdier than the one that provided a setting for the Doubleday fancy, the late nineteenth century. Nativism at home and expansion abroad excused just about any excess as patriotic striving. Between the end of the Civil War and the start of the Spanish-American War, whatever was good for America was more or less anything that somebody with a loud voice and a big stick said was good for America. By the early twentieth century, when Doubleday was formally beatified as the first among baseball’s saints, anything American was its own reward. The very language reeled from exposure to the unbridled, rapacious, and self-indulgent. Hired killers were regulators, when not peacemakers. Settling the West meant mass exterminations. Information was what the Hearsts and Pulitzers could improvise for sale. The ideal wasn’t to curb all the grabbing, but to organize it as efficiently as possible. Reconstruction meant looting, then restoration. A trust was something not to be trusted. A game was what commercialized as much joy out of an athletic activity as possible.

The game of games was baseball. It vanquished cricket as a competitor in the sports field, profited from its timely association with the extension of the railroads and development of the telegraph, and introduced parameters of mass entertainment long before such other amusements as the circus and vaudeville. Its growth in the 1860s and 1870s was unprecedented in numbers, responding as it did to both participatory exercise on the most informal athletic level and spectating habit for an admission price. The game as metaphor satisfied on any number of levels, encompassing the subtlest of mental maneuverings, the scientisms of statistical computations, and brute strength. It was physical chess that could be played by almost anyone and to a definite outcome within a short period of time.

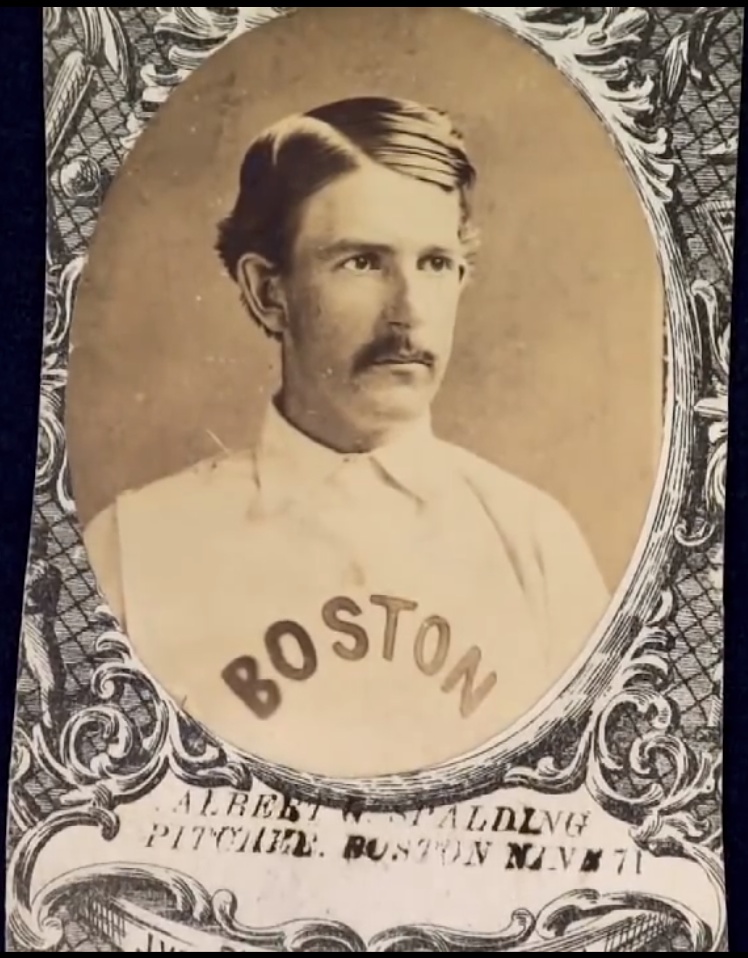

The sport’s most prominent entrepreneur over its pubescent years was Albert Spalding who went from star pitcher to team owner to publisher to operator of the global sporting goods empire that still bears his name today. Spalding epitomized the American success story even as that theme was still just seeping into both fictional and nonfictional writings as a cultural touchstone. If his beginnings weren’t laborious to the degree of an Horatio Alger protagonist, they were erratic enough to comfort notions of human progress as the ability to overcome anything associated with yesterday. Nothing measured that constantly widening distance for him as seductively as the premise that he had made his fortune in an activity -- baseball -- that not only hadn’t existed at all in the recent past but also had then suddenly arisen on the landscape as the product of wholly indigenous American genius. If he had been born too late to claim the role of inventor for himself, his own thriving remained resonant because he could see it as feeding off the immaculately original, all competing claims about the leisure activities of ancient Normans, Native Americans, Frenchmen, and Englishmen beside the point. It was a short walk from this perception to the conclusion that Destiny had a special task for him.

But Spalding was also intelligent enough to know he couldn’t walk his press clippings down to his local bank and have them considered a significant deposit. His achievements in business and in America remained an investment, and investments either grew or evaporated depending on vigilance over them. Security -- for him personally and for any enterprise with which he was identified -- meant eliminating any possible transience to his success. He didn’t need reminding that his own puritanical aversion to alcohol hadn’t prevented saloons from becoming the fastest-growing business in the country, that the dominance of his Chicago White Stockings on the diamond hadn’t protected against the regular collapse of other franchises and even entire leagues, or that the milieu of a professional baseball game was often that of a convention of bookmakers gathered for prying every penny out of the pockets of the unwary. None of these atmospherics promised long-term returns on Albert Spalding’s investments. His personal fortunes were no guarantee of anything; as often as not, they seemed to have spited prevailing trends, and how long could that be counted on to continue?

Spalding knew more than wishful thinking was required and didn’t settle for mere propaganda as a corrective. Aside from everything else, he had already tried that through years of editorials in his publications arguing (after earlier hesitations) that baseball owed nothing to such British games as rounders or the numerous variations on the transatlantic one-o’-cat. All that had gotten him were debating society disputes that confirmed nothing except the pompous, stilted rhetoric of the debaters. That wouldn’t have been enough of a response even if he had regarded baseball solely as the way he made his money. But Spalding didn’t view baseball just as a business any more than the men of influence he mingled with regularly thought of the United States as just another country on the map of the world. He could be as inspired by transcendental visions as they could and, paradoxically, for at least one very immediate business reason. As ambitious as he was for his sporting goods operation, Spalding also realized such a relatively narrow specialization left him at the children’s table while oil, steel, and other industrialists puffed away at their cigars at the adults’ table as they talked about horizons beyond the oceans. Only one thing made him their dining room equal: the idea that the major product being exported by one and all was America.

Exporting America

In 1899, President William McKinley defended the United States occupation of the Philippines by asserting that it was an American obligation to “Christianize the pagans." His pronouncement after the previous year’s Treaty of Paris that assigned Manila to Washington might have glowed for its ludicrous hypocrisy, but it also reflected how far in such a relatively short time evangelical domestic attitudes had come to further -- and rationalize -- international policy. Only a short time earlier, the economic and political expansion aims behind the Spanish-American War had been justified as a mission to free Cuba from Spanish colonialism. More broadly, between 1898 and 1920, American troops landed on Caribbean national territories twenty times with no apologies for Washington’s role as the world’s new policeman. The Gilded Age could be a heady time. In his sour appraisal of such aggressive moves some time afterward, France’s Georges Clemenceau would declare that “America is the only nation in history which miraculously has gone directly from barbarism to degeneration without the usual interval of civilization." In fact, though, no nation had abetted that development more concretely than Clemenceau’s France and not only as a venue for questionable international accords.

Between the Civil War and the beginning of the twentieth century, American attention to the rest of the world was decidedly spasmodic. Through lacerating phases of first putting the United back into the United States after the North-South hostilities and then conquering the final Western frontiers, what was going on in Rome and Copenhagen, let alone in Shanghai and Calcutta, seemed far less urgent than the potential havoc caused by boo weevils in Alabama, water shortages in California, and increasing demands by workers for trade union protections against trust managements. What didn’t threaten desolation threatened blood. It was in this context that historians such as Frederick Jackson Turner predicted a future focus on frontiers abroad as a “safety valve" for releasing pressures brought about by immigration, urbanization, and industrialization. The most recurrent bullpen for what gradually grew into an imperialistic expansion came from nineteenth-century world’s fairs that alerted other nations to what America was producing both materially and culturally as well as nudged America into recognizing the global markets off its shores. More than any bilateral economic or political agreements or exchanged state visits, the fairs offered highly suggestive glances at what might be gained from mutually deepened explorations across the oceans. Just in the years around the turn of the century, there were major international expositions in New Orleans, Chicago, Atlanta, Nashville, Omaha, Buffalo, St. Louis, and Portland. And that didn’t count American representation in fairs organized in other countries, none of them more influential than those organized in Paris in 1889 and 1900, thank you, Monsieur Clemenceau.

Constrained as he felt in pitching his baseball wares, Spalding didn’t miss the prospects visible in greater international exposure. On October 22, 1888, he set out from Chicago with his White Stockings and an assembly of other major leaguers under Giants shortstop John Montgomery Ward on a world tour for the objective of internationalizing baseball’s appeal and, not incidentally, globalizing the sales of his sporting goods company. The rhetoric around the trip about exporting baseball’s “American spirit" included attiring the Ward team in a uniform with a Stars and Stripes motif. Although the tour would later be celebrated as a prime illustration of Spalding’s promotional genius, its cardinal accomplishment was ironic in the extreme -- demonstrating that baseball was indeed truly an American sport, but in the sense that not too many other people were interested in it. The first stop after a swing through several American cities out to California was Honolulu, where the party arrived too late for a scheduled Saturday game and learned that Protestant missionaries had gained enough of a foothold to impose a ban on Sunday ball. That was about as far as Spalding got with what, in a foreshadowing of McKinley’s bluster, he called “the heathens." All King Kalakaua wanted to see was a jig by Clarence Duval, a black mascot for the White Stockings said to have “a remarkable talent for plantation dancing and baton twirling."

After a one-day stopover in New Zealand brought no converts, the party reached Australia for what turned out to be the peak of the trip. Melbourne, Sydney, Adelaide, and Ballarat were reportedly so enthusiastic about twelve exhibitions between the White Stockings and Ward’s squad that dispatches relayed to the U.S. spurred The New York Times into editorializing around the sonorous question, “Who shall say that baseball has not a mission for mankind?" (The answer was The New York Times itself, which needed many more years to concede that baseball was a worthier sport than cricket.) The dispatches from reporters traveling with the group also noted that, never one to leave showmanship to chance, Spalding ingratiated himself to the Australians by packaging the exhibitions inside more Duval jigs, cricket matches, and a parachute jump by one “Professor Bartholomew," a Michigan character whose specialty was ascending in a balloon and then bailing out for landing among the spectators. Even the reports describing the visit as a delirious triumph acknowledged that Professor Bartholomew won as much applause as the ball players.

After Australia, the tour became a concentrated study in apathy, racism, and precocious Ugly Americanism. A rough three-week sail across the Indian Ocean to Ceylon (Sri Lanka) instigated considerable grousing from the players and produced merely one five-inning exhibition. The Cingalese were described as having watched that half-game “as though we were so many escaped convicts." While Spalding amused himself with the wonders of rickshaw driving through the capital city of Colombo, his traveling companions were preoccupied with the locals to the point of paranoia. “There were hundreds of howling, chattering, grotesquely arrayed natives, with their red, white green, and blue and orange turbans, sashes and jackets," complained one member of the Stars-and-Stripes-uniformed Ward team. Another worried that the wrong call on the field would precipitate a riot, though he didn’t explain how those not versed in the game’s rules would know when any call would be wrong.

A subsequent stop in Egypt was worse. First there was a half-witted attempt to play a game in the sands around the Pyramids, then a contest among the players to fire a baseball at the right eye of the Sphinx, and then the rigging up of Duval in a catcher’s mask and gloves so he could be led around by a rope at the Cairo railway station “as if he were some strange animal let loose from a menagerie." For Spalding, the lack of enthusiasm by the Egyptians for what he was bringing them should not have come as a surprise to anybody: “In a country where they use a stick for a plow, and hitch a donkey and a camel together to draw it...it is hardly reasonable to expect that the modern game of baseball will become one of its sports."

Italy didn’t yoke its mules to camels, but it had other failings. A game in Naples appeared to launch the European portion of the tour happily when thousands jammed a cricket field under the shadow of Mount Vesuvius. But in the fifth inning a foul ball clipped a youngster, prompting what were described as “excitable" Neapolitans to swarm angrily over the field and abort the rest of the contest. Then, sixty years before an American congressman earned infamy after World War II by visiting Rome and demanding to know why the Italians hadn’t used some of their Marshall Plan money to patch up the holes in the Colosseum, Spalding arrived in the capital and wanted to know why the government wouldn’t take $5,000 of his money to clean up the arena for a game. He received appalled silence even when he raised his offer, promising that in return for access to the Colosseum, he would toss money at some local charities. He got no further in a bid to have his party received by the pope, and had to settle for playing a perfunctory game before King Humbert I and Prime Minister Francesco Crispi in the Villa Borghese. Plans to play in Florence died when the Americans were informed upon arrival that the Tuscan capital lacked suitable grounds.

The main difference between Italy and France was that the latter stop-off was mercifully briefer. As in Rome, Spalding set his sights on a venue (the indoor Exposition Hall for Industry in Paris) that was denied to him, and he had to play before an indifferent throng at the Parc Aristotique on the banks of the Seine. Summing up his experiences in Italy and France, he would be moved to a cultural insight that wasn’t all that removed from his opinion of Egyptian plowing: “In looking at the small stature of the Italian and Frenchman, and comparing it with the Englishman, Australian, and American, I was impressed with the idea that athletic sport has had its influence in developing the physical nature of the English-speaking countries." Which, in the face of some origin theories circulating at the time, took care of the possibility that Frenchmen had ever played a game similar to baseball.

The White Stockings owner got the opportunity to prove his case with the last leg of the trip -- a two-week swing through England, Scotland, and Ireland. Cordiality reigned as the teams staged eleven games in London, Bristol, Birmingham, Sheffield, Manchester, Liverpool, Belfast, and Dublin; got the Prince of Wales to attend the London contest with 8,000 other spectators and to praise baseball as “an excellent game"; and traveled from city to city on a special train put at their disposal by the Royal Family. But then there was also the Prince of Wales declaring that, as excellent as baseball might have been, he could never see it replacing cricket in his passions; railway station crowds across England showing more curiosity about the Royal train than about who was on it and why; and, having missed the memo about the cordiality, the blistering response to the games by the British sporting press. Typical of the acid comments was that of London’s Sporting Life, which hissed in part: “Baseball is the good English game of rounders which, do doubt, was taken out in the Mayflower, and was developed in the United States of America...The Americans are proud of it -- the national Columbian game. But we know all about arrested development from a study of Darwin." This article headed off any last temptation Spalding might have had to link rounders to his pastime.

If it had all ended there, with Spalding maybe telling himself that the opening of a sales office in Australia had made everything worthwhile, the tour would have been little more than an antic footnote to baseball history. But the group’s return to New York City on April 3, 1889, sparked a chauvinist orgy usually reserved for military figures who had not only fought the good fight, but had won it. An extravagant harbor reception was followed by a street parade, a celebratory exhibition game, and seats of honor at the opera. Then came a banquet at ritzy Delmonico’s on Park Avenue where the 300 guests included Mark Twain and Theodore Roosevelt.

The theme of the speechmaking at Delmonico’s was that sounded in Spalding’s autobiographical America’s National Game some years later when he extolled baseball as “the exponent of American courage, confidence, combatism; American dash, discipline, determinism; American energy, eagerness, enthusiasm; American pluck, persistence, performance; American spirit, sagacity, success." Without the alliteration but with his own literary tropes, keynote speaker Twain told the diners that what Spalding and his group had done was to bear “the very symbol, the outward and visible expression of the drive and push and rush and struggle of the raging, tearing, booming nineteenth century…to places of profound repose and soft indolence." In acknowledgment of that feat, the writer said: “I will rather applaud -- add my hail and welcome to the vast shout now going up, from Maine to the Gulf, from the Florida Keys to frozen Alaska, out of the throats of the other 65 millions of their countrymen. They have carried the American name to the uttermost parts of the earth -- and covered it with glory every time." Not to be outdone by Twain, former National League President Abraham G. Mills took the lectern for the cryptic contention that the tour had confirmed what “patriotism and research" had already established -- the purely American origins of baseball.

Even if Spalding hadn’t been predisposed to recalling the trip in such grandiose terms, he encountered few people over the following weeks ready to assist him with a reality check. The closest he came was President Benjamin Harrison, who spent a few stiff minutes with the tour members in Washington, making it evident that it would be beneath his dignity to be seen at a ballgame; but then Harrison had just sidled into the White House on the strength of an Electoral College vote that had negated a popular consensus for Grover Cleveland, so, president or not, his was hardly the most authoritative voice in the land. More typical was Jersey City Mayor Orestes Cleveland burbling about how “six months ago these young men went abroad to fight, not like gladiators covered with armor, but covered with their American manhood, and they have come back covered with laurels, to place them on the fair brow of the American girls." In Philadelphia, where the reception was as boisterous as in New York, Colonel Alexander McClure, a Republican Party powerbroker, one-time confidant of Abraham Lincoln, and publisher of the Philadelphia Times, was quoted as telling another banquet: “I would like very much to get a little of the baseball theory into our politics. I would like to get it introduced into social life, into the churches. I do not know a place or thing, system or class or method that would not be improved by your code of ethics, for an institution that teaches a boy that nothing but honesty and manliness can succeed, must be doing missionary work every day of its existence. It will not only make a high standard of baseball men, but make the whole world better for its presence."

By the time the final festivities had been played out in Chicago on April 19, Spalding had every incentive for boasting that the tour’s financial loss (he calculated some $5,000) and missionary futilities had actually been an ideological romp. Nothing remained of the six-month voyage but those few good days in Melbourne and Sydney. Shortly afterward, in the 1889 edition of his baseball guide, he began preaching in earnest baseball’s total independence from rounders and other European games, though not yet with specific reference to Doubleday or to any other native turned up by that “patriotism and research."

Myth Makers

One of the more familiar routines of the late comedian George Carlin centered around the contrasting languages of baseball and football. The thrust of Carlin’s monologue was that baseball, with concepts such as the sacrifice and heading home, represents a dovish ideal as opposed to football’s glorification of the bomb, the blitz, and any number of other images borrowed from the military mind. As shown by the orations delivered after his world tour, Spalding and his contemporaries would have found such an interpretation of the sport intolerable. On the contrary, they could not discuss baseball without reaching for analogies reeking of the bellicose. In an age in which war heroes were the most prominent public idols, the pitcher and catcher who formed a battery were presented as civilian soldiers, wresting victory from the enemy at all costs. Pitchers fired; comeback rallies came in volleys; wins were conquests. It was hardly a giant step from this mentality to the conclusion that if baseball had a single founder, it had to be someone incorporating military virtues, and certainly not a foreigner.

But that still didn’t lead automatically to Doubleday, not even for Spalding. Indeed, because of business affairs and then such prestigious appointments as heading the United States delegation to the Olympics, almost two decades passed from the start of his full-bore insistence on a single American creator to the naming of Doubleday as that visionary. Among other events in that interval were Doubleday’s death and a public waking at New York City’s municipal hall -- when not a single eulogist managed to utter the word baseball. There was also the discovery that sixty-seven diaries kept by the general maintained the same silence, that the closest he came to mentioning athletic activities of any kind was in urgings to himself to take more walks. Clearly, Doubleday hadn’t been too impressed by his contribution to an activity that, by his death in 1893, had grown into a very big business.

But by the 1890s, baseball was more than a significant economic sector. It had also degenerated into a setting for corporate venalities and boardroom double-crosses, fixed games and other gambling excrescences, mass public drunkenness, and routine violence involving players, fans, and umpires. In one notorious incident, women tore up a Washington stadium after their Adonis of the moment had been tossed out of a game, putting an end to the gentility images sought through Ladies Day promotions. The national pastime, as its publicists had come to call it with a straight face, felt itself crumbling internally and under siege externally.

Spalding’s solution to the first problem came out of a Monopoly Capitalism primer: eliminate the competition and annex its useful parts for a single, more controllable order. In this spirit, his National League stomped out both the Players League and the American Association at the beginning of the decade. The external pressures were trickier. Never had there been so many rivals for the baseball dollar as in the 1890s: everything from bicycle races, football, and basketball to vaudeville, amusement parks, and movie arcades beckoned with entertainment alternatives. The Spaldings of the surviving National League were hardly on a window ledge: they still made enough profit to lobby sympathetic reporters not to publish attendance figures lest tax collectors amass too much information. But the long-term prospects for the industry were something else. Things were simply too messy.

One tested recourse for enterprises in difficulty is an appeal to patriotism, and scoundrels of the period wrapped themselves in the flag to justify everything from charging higher sugar prices to paying immigrant workers substandard wages for unloading sugar cargoes to invading foreign sugar cane fields. But baseball was neither a table staple nor an arena of civic obligation. Leisure industries were still only approaching the frontier of the social imperative they would clutch as a prerogative in the twentieth century. Moreover, entrepreneurs like Spalding had been highly visible amid all the executive chamber manipulations and scandals attaching themselves to the sport; whatever self-righteousness they found in themselves for their actions, that did not translate easily to attracting the discretionary income of the family audiences increasingly viewed as the lifeblood of mass entertainment. If there was any modesty at all in the vision Spalding had of his activities, it was in his practical concession that people like himself were insufficient for propagating the religion of baseball. The most successful of self-made men got their hands dirty, and if baseball was about anything in its importance to America, it was in its emblematic place above the fray. Hadn’t all the Mark Twains, New Jersey mayors, and Philadelphia newspaper publishers said so? The game’s theologies and moralities could be debated endlessly, but its mythology had to be unquestioned.

Myth-making was an ardent pursuit in late nineteenth-century America. A bloodless Protestant ethic might have still found compatible application to industrial society, but personal, consoling configurations of higher powers were not as superfluous in teeming metropolises and across vast prairies and mountains as they had been across the Atlantic in English villages and German squares. Even without factoring in the spread of Catholic iconography thanks to Irish, Italian, and Polish immigrants, abstract contemplations showed more of an inclination to be voids waiting to be, if not filled, at least encircled by the hyperbolic, the legendary, and the fictional. Big countries made for punishing senses of isolation, and human agency acquired new value in morality tales through Uncle Remus, in romantic impressionability through the likes of Jesse James and Steve Brodie, and in commercial fantasy through Paul Bunyan. Closer to home plate, Frank Merriwell was the model fabrication of a sturdy American ballplayer’s ideals.

Spalding had a particular vantage point for this outlook from his southern California home at Point Loma. Under the influence of his long-time mistress and then (following the death of his first wife) second wife Elizabeth Mayer Churchill, he had become fascinated with the teachings of Helena Blavatsky, attending meetings of her Theosophy Society in the San Diego area. Among the priorities of Theosophy’s speculative mysticism was a study of world myths -- their origins and impact on various cultures in the interests of “knowing the divine." None of this was to be confused with explorations of the disarmingly folkloristic. In contrast to, say, a Johnny Appleseed or to some of the suspect tales clouding the figure of a Buffalo Bill, a Zeus or a Kali did not entertain conjectures about human prototypes; they had always been divinely above the fray, with no responsibility for the sordidness of daily living. If his contemporaries could be tickled by the legendary for enlarging the human, the characteristically aloof Spalding was enthralled by the mythical as remote from the human, as Olympian impassivity not to be compromised by social or historical vicissitudes.

And he wasn’t the only one. Doubleday had been active in the East for decades as a Theosophist. Assertions that Spalding had no links to the general prior to proclaiming him baseball’s prime mover, a commonplace for years among skeptics of the pure American invention fable, were in fact not accurate. Whether or not they ever shook hands, and time and geography factors indicated they did not, they still had the meeting ground of Theosophy. Even more critical, Elizabeth Spalding’s long association with the movement, extending back to the East before Point Loma, had certainly put her together with Doubleday when he had been so involved in the Theosophy Society that he had served as its vice-president for nine years and had remained a board advisor practically up to his death. Given her connection with the men, in different parts of the country though it had been, it is hardly surprising that some researchers have attributed a critical role to Elizabeth in the selection of Doubleday as the pure American pioneer her husband had been seeking for years.

There is no hard record of Spalding seriously considering other candidates for his role of a single American inventor. He would contend that he did, but the only collaborating names to emerge (Alexander Cartwright, for instance) had been rejected in his speeches and articles for some time. Sincerely or disingenuously, he formed a panel of notables in 1905 aimed at resolving the question once and for all; when not his employees, its members were the very like-minded, such as the one-time National League president Mills, he of the “patriotism and research," who had also served under Doubleday in the Union Army. It was at this point that, in true Gilded Age fashion, the fabulous encountered the purposive and waylaid much of the narrative to come.

The fabulous was supplied by Abner Graves, a 71-year-old Colorado mine owner and real estate investor, who, during a trip to Akron, Ohio in April 1905, read an article in the local Beacon Journal in which Spalding reiterated his belief in a single American founder of baseball and asked readers if they could provide him and his commission with any information supporting that view. Graves provided -- and provided and provided. In letters to both the Beacon Journal and Spalding’s commission over the next couple of years, he asserted that one day in 1839, in the upstate New York town of Cooperstown, Doubleday, then a twenty-year-old cadet at the United States Military Academy, had interrupted a game of marbles among some kids and sketched out the basics of baseball for them in the dirt being used for their game. That was about the only part of his story that remained even relatively constant in his correspondence and in voluminous newspaper interviews.

In his various accounts, Graves sometimes had only been told of the Doubleday demonstration by the boys there at the time, other times had himself been one of the marble shooters, and still other times had played in a game for testing the Doubleday regulations. He wasn’t all that consistent about his age for the epochal event, either, fluctuating between five and eighteen depending on the role he assigned himself in the yarn being shared. When he hadn‘t been down on his knees squirting his shooters, he had been a student at Green College, where Doubleday had visited (presumably on leave from West Point), and led a group of teenagers out to some campus sand to demonstrate his inspiration. To bubble the stew a little more, he admitted it might have been 1840 or 1841 instead of 1839, but, unfortunately for fact checkers, the others present for the demonstration were all dead except for one gravely ill soul who had been emanating death rattles in his bed. Neither the vagueness nor the contradictions alarmed the Colorado reporters who flocked to him periodically, so they could satisfy their editors with another headline identifying the Man Who Invented Baseball and The Man Who Saw Him Inventing It. (Undoubtedly fueled by the booze always within reach, the reporters also obligingly passed along such tidbits as Graves’s alleged adventures as a Pony Express rider eight years before there had been any such thing as a Pony Express.)

For the most part, historians have given Graves a pass that something took place near Cooperstown in one of the years he mentioned, rejecting the idea that he might have just seen the Spalding article, taken another drink, and decided on a little mischief. The most benevolent interpretation was that many seventy-one-year-olds were hard put to recall specifics about their fifth year. With one exception, his tale(s) simmered out of the public eye for a good three years since it wasn’t until March 1908 that Spalding’s commission came out with its finding that America owed its national pastime solely to Doubleday. But the exception was notable. It was an August 1905 article in the Point Loma Theosophist Society organ The New Century Path that both proclaimed Doubleday as the inventor of baseball and, his modesty slipping, hailed Spalding for his supreme role in American sports. Citing the assertions made by Graves in his letters, the Path said of Doubleday: “It is of interest to note the fact that it is to this staunch Theosophist…that the national game of Base Ball owes not only its name, but also in large degree its development from a simpler sport, or, indeed, according to some writers, its very invention." The newspaper, headquartered within walking distance of the Spalding home added of its most distinguished follower: “It is also of interest to note that another well-known member of the Universal Brotherhood and Theosophical Society, Mr. A.G. Spalding…is universally known as the patron of the development of Base Ball and athletic sports generally; and it is certainly due to Mr. Spalding that so large a proportion of our American youth have a love for the health-giving and manly games." Given his publication background and position within the Point Loma organization, Spalding himself was presumed to have written the article.

When the commission’s report finally came out in March 1908, it included references to Graves’s letters, but not to several other things, among them the fact that the man had been institutionalized on two occasions before taking his fateful trip to Akron. To some extent, the report was merely a ripple in a peak tide of America First waves that year encompassing triumphs at the Olympic games, another victory in a heavily-promoted around-the-world auto race, and the election of William Howard Taft as president after his years as governor of the reputedly beaten “pagan" guerillas in the Philippines. History was still being written by the winners, and in this particular case would continue to be accepted as fact all the way to 1939 when baseball officials formalized the Spalding commission’s claims by marking the centenary of the reputed marbles game by welcoming its first five members to the Hall of Fame in Cooperstown. What endured alongside national chauvinism and institutional self-interest was the astounding credulousness of so many people for so long about the Doubleday fairy tale.

Innocent Until Proven Innocent

Baseball historians of recent date have spent a great deal of labor uncovering games before 1839 that document the falsity of Doubleday’s supposed achievement, going further and further back into the past to single out one forefather after another for the credit fancifully accorded the general. Earnest as all the research has been, it has brought to mind the digging of a tunnel that within a millennium or two should open out into the China Sea. None of it has tainted the conclusion of David Block in his Baseball Before We Knew It that “baseball evolved from a matrix of early English folk games, and it follows that baseball’s rules were borrowed and shaped from those same traditional pastimes. The process involved unknowable numbers of children and youths experimenting in fields and churchyards and village greens over a period of centuries, with the resulting wisdom passing unobtrusively from one generation to the next." At a minimum, such a theorized tradition is far more believable than the testimony of Graves’s garrulous Wilford Brimley-like character who when he wasn’t bending his elbow and conjuring up personal exploits for reporters drawn to him for a lazy assignment, was shooting his wife because he feared she was poisoning him, was denying during his murder trial that she was dead, and was being locked away in an asylum until his death at ninety-two in 1926. Having died eleven years earlier, Spalding missed this last, crazed eruption from his most conspicuous accomplice in the Doubleday fantasy.

By the time he formed his panel in 1905, Spalding could have been justifiably accused of having wasted a great deal of time, articles, and speeches if he hadn’t already established some guidelines for recognizing the candidate he was seeking. Based on predilections he had never disguised and that were fully in tune with his era, one important consideration would have been the military background of the candidate. Another was that the candidate be dead, not only because of the time span involved but also because a corpse wouldn’t be able to indulge in any behavior that might embarrass the sport the way it had been embarrassed by its players, executives, and fans for quite some time. But an equally critical public relations problem for the sport had been that during his lifetime the candidate had had absolutely nothing to do with baseball. The priority was the American Game, to be thought of as being played in Elysian Fields as much as in the ballpark across town, and if that didn’t demand angels in the outfield, it at least required somebody motivated by more than a chance to tear tickets at turnstiles, open concession stands for a captive audience, and count the take. Ideally, the originator had left the rules of the game on a doorstep, rung the bell, then scurried back to his celestial abode, never bothering about balls and strikes again.

In meeting all these criteria, Doubleday represented a deus ex machina for Spalding, to the point that Graves might have seemed a little too good to be true. But conspiracy theories were not needed, not with Spalding being surrounded by such Doubleday boosters as Mills on the commission and by Elizabeth at home. If anything, Graves’s bibulous character would have given the sanctimonious Spalding serious pause before entrusting what had become a life’s mission to somebody whose chief lease on reliability was that he was deemed “colorful." But what Graves also offered was the most classically mythological cover of all: mist. The right sliver of mystery was even insurance that the game would never be reduced to the transient runs, hits, and errors of a scoreboard.

There was a great deal of mist at the dawn of the twentieth century, and usually when it cleared, “purely American" was to be made out. Such triumphalism would have no equal until the Cold War, when the press agency Tass and the Communist Party organ Pravda would claim regularly that the Soviet Union had been first with just about every genial idea and revolutionary invention reaching the public. One of the numerous examples in Spalding’s time was the fledgling industry of motion picture in which, despite decades of achievements by Frenchmen like Georges Melies and the Lumiere brothers, not to mention several Britons and Germans, Thomas Edison was all but canonized as the medium’s inspiration. In fact, that was a symptomatic case of control being confused with creativity. Where Edison’s authority actually came from was not from some original stroke of imagination, but from his control of patents and copyrights bought or finagled from the true inventors. And why apologize for that? There was no guilt attached to trying to Christianize pagans, whether they were in the Philippines, Sri Lanka, or upstate New York.

From guest contributor Donald Dewey

November 2017

|