Although he stopped fighting seventeen years before I was born, Joe Louis may be the first boxer whose name I knew. I grew up in Detroit, where Louis spent his teenage years and discovered the sport he went on to dominate from the mid-1930s through the 1940s. When an arena was built in the city in the 1970s, Mayor Coleman Young successfully pushed to have it named for the fighter he and countless others of his generation admired. Several years after that tribute’s construction, another monument to the great champion was placed at a major intersection downtown. I can’t clearly recall a time when I didn’t know the name so many people loved. Regardless of when I first learned about him, I came to believe Louis deserves to be remembered - and to suspect that he won’t be.

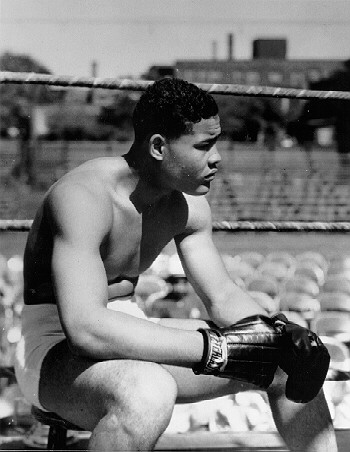

If any athlete ever looked like an all-time great with real claims to the designation of hero, Louis was the man. As boxer, he achieved an unbeaten and probably unbeatable record, reigning as heavyweight champion of the world for a dozen years and successfully defending the title more than two dozen times. He handily dismantled racist ideologies and insulting stereotypes in bout after bout, though one in particular had profound and lasting global impact. He conducted himself with stoic grace and instilled pride in millions of people suffering hardship. Though some athletes and other public figures of later generations might have wished he had been more outspoken about injustice, he advocated equality in his own way and left no trail of foolish or hateful statements. Even if his post-boxing days were less inspiring, his earlier achievements were truly phenomenal.

During his heyday, Louis was one of if not the most written about Americans in U.S. newspapers, as authors of the numerous books about him often mention. He became a fixture in the mainstream press at a time when it was unusual for black people to be written about regularly, and positively, outside of newspaper published by and for black audiences. Both while still fighting and afterward, Louis (with co-writers) authored autobiographies: 1947’s My Life Story and 1953’s The Joe Louis Story (both with Chester L. Washington and Haskell Cohen) as well as 1978’s Joe Louis: My Life (with Edna Rust and Art Rust, Jr.). Both while Louis was alive and afterward, myriad biographers scrutinized his experiences, usually in order to interpret his rich symbolism, to account for his social impact and to penetrate his stony facade and solve the enigma of his personality - or try to.

Necessarily, the many biographies of Louis cover the same well-mapped territory: his birth in an Alabama sharecropper’s shack in 1914; his father’s commitment to the Searcy State Hospital for the Colored Insane two years later; his mother remarrying to create a family with thirteen children; his stepfather Pat Brooks taking the family to Detroit in 1926; his exchanging the violin his mother wanted him to play for the boxing gloves he discovered suited him better; his signing with numbers-runners John Roxborough and Julian Black as managers and Jack Blackburn as his trainer and turning professional in Chicago in 1934; his rapid ascension in the heavyweight ranks; his first setback when defeated by Max Schmeling in 1936; his winning the title the following year; his avenging the loss to the German Schmeling in one of the most symbolically charged bouts in history; his joining the Army and going on morale-raising tours for the troops during World War II; his first retirement in 1949 and his unfortunate return to boxing the following year; and his subsequent “degrading” work as a wrestler and then as a greeter at Caesars Palace in Las Vegas. Of course, his biographers also address non-athletic matters as well, such as his burdensome debt to the Internal Revenue Service, his marriages to three women and affairs with many more, his love for golf, his drug use; his own mental illness; and his death in 1981.

If Barney Nagler’s Brown Bomber: The Pilgrimage of Joe Louis (1972) were the only extant biography, then correctives would be desperately needed. It’s the tabloid newspaper equivalent of biography. It begins with the former champion’s commitment to a psychiatric hospital in 1970, as if that were the key moment in his life and a logical starting point for his story. Nagler shows more interest in Louis’s infidelities than in his athletic accomplishments. When not pondering the “dark despair” boiling “within the cauldron” of Louis’s troubled mind, he turns to what he calls “Joe’s associations with other women,” a group that included singer Lena Horne, actress Lana Turner, figure skater Sonja Henie and countless less famous paramours.

Beyond concentrating on what journalists at the time deemed private matters (and what Louis managed with discretion during his fighting days), Nagler presents Louis as no more than a basically decent fellow (except to his wives, that is) with an impressive ring record. Black Americans might have thought he amounted to more than that, he allows, but they were wrong. “Negroes ran through the streets cheering their new hero” after Louis beat former heavyweight champion Max Baer in 1935. “In their exultation they found a strange new hope that everything would get better for everybody among them. The next morning life was no better.” Certainly an up-and-coming black boxer’s second victory over a white ex-title holder did not immediately erase any social ills, but rather than consider the significance of such unusual exultation and hope, Nagler dismisses all of it as so much nonsense. Louis defeating James J. Braddock in 1937 to claim the title should not be taken to mean much either, Nagler counsels readers: “Joe Louis was the world heavyweight champion, and, yet, nothing had changed, either inside the arena or outside.” The reality that some fans might take special pride in the fighter’s win irks Nagler: “On Chicago’s South Side black Americans came charging out of their houses, shouting jubilantly, cheering their hero. But he was not really theirs; he belonged to everybody.” Well, not quite.

Long before he became heavyweight champion, Louis inspired and heartened black Americans with his ring exploits, especially when they involved victories over white boxers. Although Louis beat Baer in New York City, spontaneous celebrations sparked around the country. Richard Wright witnessed the events in Chicago that Nagler tries to whitewash. “On Chicago’s South Side five minutes after...Joe Louis’ hand was hoisted as victor in his four-round go with Max Baer, Negroes poured out of beer taverns, pool rooms, barber shops, rooming houses and dingy flats and flooded the streets,” Wright reported in New Masses. The eventual author of Black Boy and Native Son (as well as a song about Louis that Paul Robeson sang) makes plain that revelers took Louis as more than "only a sportsman" even then. And they didn’t see him as belonging to all equally. Louis demonstrated that he did not fear Baer, as sportswriters predicted he would, but he also lent courage to others. “We ain’t scared either,” Wright imagines South Side celebrants thinking. “We’ll fight too when the time comes. We’ll win, too.” In his second year as a professional fighter, Louis had already become a representative figure. His success did not belong to him alone even if it did not yet belong to everyone. That would come later.

When Louis ascended to the pinnacle of his profession, he altered how black Americans in particular thought and behaved. When Louis took the title from Braddock, “all the Negroes in Lansing [Michigan], like Negroes everywhere, went wildly happy with the greatest celebration of race pride our generation had ever known,” Malcolm X says in his autobiography. “Every Negro boy old enough to walk wanted to be the next Brown Bomber.” His brother, Philbert, had already started boxing, and Louis’s championship spurred thirteen-year-old Malcolm’s entry into the ring. He quit the sport after two losses to the same white bantamweight convinced him he ought to choose another path, but the pride Louis fired did shape who he became.

Louis realized that people expected much of him and had made large psychic investments in his work. At the end of the year in which he beat Baer, Louis went to church with his family and heard a preacher tell the congregation that through his masterful fighting he was uplifting the spirit of his race, that he was one of the Chosen. “Jesus Christ, am I all that?” Louis remembers asking at the end of an anecdote much liked by biographers. Nevertheless, as Nagler tells it, Louis’s story is no more than that of an “absolutely decent person” and a truly awesome athlete, albeit one who made poor financial decisions and who, late in life, had mental health problems that saw him fear assassination by the Mafia and methodically tape over air vents in hotel rooms in order to thwart the organization’s attempt to gas him.

Even the one event more than any others that elevates Louis above the elite rank of top-tier professional athletes - the victory over Schmeling - Nagler regards as just a bout with too much fuss made about it. Though it was “a mere sports spectacle,” though it was “just a prize fight,” Nagler explains, “America’s misguided evaluation of the fight” caused it to be seen as some kind of “national cause.” While Louis’s own self-conception - as a boxer and not a politician - may mesh with Nagler’s view of him, the fighter still did have a profound effect on certain groups and society at large. If at the end of 1935 Louis “was the concentrated essence of black triumph over white,” as Wright says, then just two and a half years later he became something even more symbolically powerful. Black Americans were not the only people to see Louis’s second fight against Schmeling as bigger than a sporting event. Nor was it only about U.S. race relations, as several commentators and historians point out. “It was not just black against white, which was combustible enough,” David Margolick explains in Beyond Glory: Joe Louis vs. Max Schmeling, and a World on the Brink (2005), “but youth versus age; raw talent and instinct versus experience; freedom against fascism; and, in its own way, the Jews versus Adolf Hitler.” Americans were not the only people looking at the fight through ideological lenses. The Nazis hoped Schmeling would bolster faith in Aryan supremacy by defeating Louis for a second time.

The outcome of this tense international drama had real consequences. “Nobody on either side of the Atlantic viewed Louis and Schmeling II as anything less than the personification of Good vs. Evil,” Budd Schulberg writes in Sparring with Hemingway (1995). “If Schmeling won, the shadow of the swastikas would darken our land. If Louis triumphed, Negroes, Jews, anti-Nazis, pacifists, and everyone who yearned for an order of decency without violence would feel recharged and reassured.” And when Louis won, they were. They were also emboldened. “When Herr Schmeling cried out in surrender we were ready psychologically to take on the Luftwaffe and the Waffen-SS,” Schulberg remembers. Nagler may want to treat Louis’s first-round knockout of Schmeling as just another battle between boxers, but too many people shared Schulberg’s outlook to deny the reality of the psychological impact without distorting history.

Fortunately, Nagler’s Brown Bomber has been supplanted by works imbued with better understanding of the real significance underlying public perceptions of a figure who was first regarded as a representative of a race and then of an entire diverse country. Even if Louis ultimately was just an athlete, he did change attitudes and propel the cause of civil rights in the United States. Writers writing about Louis routinely cite Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Why We Can’t Wait (1964) to illustrate how much the boxer mattered to black Americans:

More than twenty-five years ago, one of the southern states adopted a new method of capital punishment. Poison gas supplanted the gallows. In its earliest stages, a microphone was placed inside the sealed death chamber so that scientific observers might hear the words of the dying prisoner to judge how the human reacted in this novel situation. The first victim was a young Negro. As the pellet dropped into the container, and gas curled upward, through the microphone came these words: “Save me, Joe Louis. Save me, Joe Louis. Save me, Joe Louis...”

The story is apocryphal, as Margolick convincingly shows in Beyond Glory, but writers still point to it as indicative of how people thought of Louis, even if it is not factually accurate. “Not God, not government, not charitably-minded white men, but a Negro who was the most expert fighter, in this last extremity, was the last hope,” King said, and the legend took hold, Margolick believes, “because it seemed so plausible.”

Much has been made over the years of Schmeling claiming to “see something” - or “seez somezing” as Nagler insists on transcribing the famous remark. (One of the least satisfying aspects of much writing about boxers is the way journalists render their speech. Too often, especially in text from the first two-thirds of the twentieth century, this involved using fabricated dialect designed to make black athletes appear ignorant. Nagler doesn’t perpetuate this racist practice; instead, he mocks a white fighter whose first language wasn’t English.) Schmeling, the story goes, astutely perceived Louis’s tendency to leave his left hand low for a fleeting moment after throwing multiple left hooks, thereby exposing the side of his face to opponents’ right hands. Schmeling took complete advantage of this insight, but he was hardly the only observer to spy the weakness. Former champion Jack Johnson had been remarking on it for months prior to the first fight between Schmeling and Louis. Yet even Louis’s shortcomings become strengths in biographies that veer close to becoming hagiographies. He learned from the defeat to Schmeling in 1936 - the only one he suffered until losing to Ezzard Charles in 1950 and Rocky Marciano in 1951 - and rededicated himself to training and honing his stellar skills.

The Louis literature contains some especially striking overlaps. Chris Mead and Donald McRae, for instance, end their books in virtually identical fashion. Both quote from the eulogy that Jesse Louis Jackson delivered at the funeral held at the Caesars Palace Sport Pavilion and note that the reverend’s parents named him in part for the fighter. McRae - who distinguishes his take on Louis from other writers’ by braiding it with the story of the boxer’s exact contemporary, friend, and fellow trail blazer Jesse Owens - also points out that the speaker’s first name was bestowed to honor the Olympic runner. Still, the concluding paragraphs of Mead’s Champion: Joe Louis: Black Hero in White America (1986) and McRae’s Heroes without a Country: America’s Betrayal of Joe Louis and Jesse Owens (2002) are almost uncannily alike, unintentionally illustrating the difficulty of doing something different with such a frequently retold life story.

Randy Roberts aims to make a unique contribution not by mourning the passing of the man but by announcing the death of the legend. He does not provide new information in Joe Louis: Hard Times Man (2010). Instead, he offers an unfamiliar perspective, presenting Louis as a hero for his era whose relevance has since faded. In some ways, he does what others did before him. Mead, in a hard biography to beat, concisely conveys what made Louis so much more than just an awe-inducing athlete: “Every time he stepped into the ring against a white opponent, Louis refuted theories of white superiority.” By beating these men, and especially by demolishing a fighter associated with the Nazis soon before the start of the Second World War, Louis affected how people thought of him and others with dark skin. Long before Jackie Robinson began playing major league baseball, Louis secured what at the time was the most prestigious prize in sports, which on its own would have made him historically significant. Yet his actions resonated far beyond the sporting realm. “He had opened sports to blacks and made athletics a cutting edge of the civil rights movement,” Mead writes. Louis contributed to social change, even if that was never his aim. The simple fact of a black man winning contests against whites in the 1930s, “when American racism was implacable,” made him “a revolutionary,” in Mead’s estimation. The biographer also calls revolutionary the popular understanding of the fight staged on June 22, 1938. “There was no question that the American public attached a strong symbolic importance to the second Louis-Schmeling fight and accepted Louis - a black man - as the representative of American strength and virtue.” Even during his brief and less glorious career as a wrestler in scripted battles between one-dimensional heroes and villains, “Louis always played the good guy.” Roberts restates these same essentials - as have earlier chroniclers such as Gerald Astor, Anthony O. Edmonds, and Rugio Vitale - but he goes on to suggest that being a good guy no longer satisfies the hunger for heroes.

One reason for Louis’s diminishment is the marginalization of the sport he once dominated. In order to explain the meaning and importance of the boxer’s life and work, Roberts spells out the significance of a man like Louis accomplishing what he did when he did. “Boxing is no longer relevant to most Americans,” Roberts concedes. “For many Americans today,” he goes on to say, “it is difficult to remember a time when boxing was vitally important.” In the late nineteenth century and for much of the twentieth, many people could identify, and identify with, the world heavyweight champion. Because the same cannot be said of the early twenty-first century, Roberts chooses to “provide a detailed consideration of the meaning of that title for Americans.” In doing so, he reviews in detail the careers of such fighters as John L. Sullivan, who straddled the bare-knuckle and modern gloved eras, and Jack Johnson, the first black heavyweight champion (and the subject of Roberts’s 1983 book Papa Jack). Roberts says Sullivan’s moment saw “a new construction of the meaning of boxing,” and that “the critical transitional figure” became “an irresistible icon of strength and masculinity.” Those in the Sullivan mode “spoke the new language of men, the sparse vocabulary that would become the hallmark of Jack London, Ernest Hemingway, and Norman Mailer.”

One of Mailer’s boxer narrators refers to “the intelligence of good athletes, practical intelligence,” and Louis certainly possessed plenty of this kind of intelligence not usually reflected on school report cards. Louis, a stutterer as a child, never became a confident speaker and never sought to use his position to promote a cause. Regarding Louis’s unsmiling, taciturn demeanor, McRae says the champ knew “it was better to be a silent intimidator than some clown they could easily mock” and that “they” could mean different people at different times. What condescending journalists first took as a sign of ignorance later came to look like a combination of temperament and deliberate preservation of dignity. “The heavyweight crown carried social and cultural weight,” Roberts observes. Louis added something new to its symbolic meaning as “the most visible expression of racial progress,” as the epitome of male strength who, rather than being vilified as Johnson had been, was embraced and honored.

An episode from early in Louis’s career speaks volumes about the fighter - and those who write about him. Both Roberts and Nagler report Louis’s refusal to eat a slice of watermelon in front of photographers. Roberts makes better use of it, capturing something essential about Louis’s personality: “In his quiet way, he refused to be a party to his humiliation.” Roberts sees an insistence on dignity in the fighter’s unwillingness to conform to racial stereotypes. Nagler simply depicts Louis as sulky. Knowing that the boxer actually did like watermelon, which only Roberts mentions, makes all the difference.

Although not inclined to make grand pronouncements, Louis did occasionally fire off a good line regarding matters of immediate personal concern, such as his oft-repeated remark prior to his first fight with fleet-footed Billy Conn: “He can run, but he can’t hide.” Ironically, Conn, who going into the thirteenth round was ahead on the judges’ scorecards, probably could have won a decision if he hadn’t chosen to knock out the much bigger Louis - if he had run, in other words. Subsequently, Conn asked Louis, “couldn’t you have let me borrow your title for just a little while? Just for six lousy months?” Louis responded: “Billy, I let you have it for twelve rounds, and you didn’t know what to do with it. What makes you think you could have kept if for six months?” Much later, during a joint television appearance, Muhammad Ali described having had a dream in which he knocked out Louis, who replied, “Don’t even dream it.”

Athletes (and others) a generation (or more) after Louis may have wished he had been more vocal about injustice instead of letting his accomplishments speak for themselves. In the 1960s, “Joe Louis’s image as inoffensive and popular with whites seemed dated and less worthy of respect,” Mead says. Illustrating the point, Nagler quotes former Cleveland Brown running back Jim Brown as disputing the claim that “Louis did as much for the black cause as Muhammad Ali.” The reserved older boxer may have won over white sportswriters precisely because of his disinclination to complain. “He could have been, should have been, more outspoken in the problem of blacks,” the football star insists. Ali’s attitude toward Louis (like much of his thinking) shifted over time. “Louis had been Ali’s childhood hero when every Louis victory over a white man had somehow avenged the racism of America, had been a real, physical repudiation of white supremacy,” Mead writes. (Born in 1942, Ali actually grew up hearing about, rather than experiencing first-hand, the years of Louis’s greatness.) Later, as champion himself, Ali called his former idol an Uncle Tom and swore he would “never end up like Joe Louis.” Yet, in 1976, the same year his precursor-disrespecting autobiography The Greatest: My Story appeared in print, Ali invited Louis to spend a week and a half at one of his training camps and offered the strapped former champ thousands of dollars.

Much earlier, Louis had criticized Ali in a manner typical of the older man’s middle-of-the road outlook. After defeating Sonny Liston to become champion in 1964, Cassius Clay announced his membership in the Nation of Islam and changed his name to Ali. Louis disapproved. “I’m against Black Muslims, and I’m against Cassius Clay being a Black Muslim,” he declared. “I’ll never go along with the idea that all white people are devils.... The way I see it, the Black Muslim wants to do just what we have been fighting against for a hundred years. They want to separate the races and that’s a step back when we’re going for integration.” In Joe Louis: My Life, says he “understand[s] better” why a person might change his religion and his name even though he had first disagreed with Ali’s decision to do so. (As an amateur Joe Louis Barrow chose to be “plain Joe Louis” to keep news of his fights from his mother.) The state of Louis’s health when his last autobiography came out raises questions of its reliability - about how much the Rusts tried to make look Louis up-to-date rather than out of it. (To give but one example, Louis claims in the memoir that a prostitute introduced him to drugs by literally injecting him when he had his back turned - a story Mead finds “very hard to believe.”) Nonetheless, in retrospect, his statements in the mid-1960s sound more reasonable than much of what Ali was saying at the time.

While Louis did not regard himself as a spokesman, and his silence about racism did not sit well with more militant types like Brown and Ali, it would have been practically impossible for Louis to have excelled professionally if he had openly defied whites in the 1930s and 1940s, especially after Johnson had done so decades earlier by both besting and belittling Great White Hopes and consorting with and marrying white women. Louis’s trainer initially hesitated before working with the boxer for precisely this reason. “It’s next to impossible for a Negro heavyweight to get anywhere,” Jack Blackburn recalled telling Louis. “He’s got to be very good outside the ring and very bad inside ring.” Johnson had been indisputably the latter and enthusiastically not the former; Roxborough and Black set out to make sure Louis met both requirements. Although his mangers scrupulously shaped his inoffensive public image, Louis’s face already the mask they made for him. “Louis’s silence and seeming conservatism were more than good public relations, however; they were his personal style,” Mead writes. Roberts reiterates the efforts of the fighter’s handlers to style him as absolutely nothing like Johnson, which suited Louis just fine. By temperament, Louis was the type of sportsman William Hazlitt favors in “The Fight” (1822), an essay specifically about the December 1821 match involving Bill Neate and Tom “The Gas Man” Hickman and more generally about the “Fancy” - the assortment of rowdies and aristocrats following the bare-knuckle fight game. Hazlitt disapproves of Hickman’s pre-fight remarks about his plans to butcher Neate. “It’s was not manly, ’twas not fighter-like,” he says of the insulting prediction. “If he was sure of the victory (as he was not), the less said about it the better. Modesty should accompany the Fancy as its shadow. The best men were always the best behaved.” Journalists in the 1960s said the same thing (in era-appropriate idiom) about Ali’s name-calling and winning-round-forecasting, while in the 1940s, after realizing shyness did not indicate ignorance, they praised Louis’s modesty and politeness.

As Louis’s example illustrates, treating a person as an emblem - whether as a Black Hercules or an Uncle Tom - strips him of his individuality. Even latter day lionizers risk reducing Louis to a victim despite themselves. In Heroes without a Country, McRae focuses on the racial prejudice Louis and Owens endured. He blames Louis’s less respectable bids for cash, as well as his drug problems and mental illness, on his being “hunted” by the IRS. Regarding Louis’s financial problems, Mead more sensibly observes: “He sorely needed good advice but never got any.” Although some (like McRae) regard the federal government hounding Louis for unpaid taxes and penalties as unfair, “the IRS was just doing its job,” in level-headed Mead’s opinion. Just as Louis always thought he was just doing his job - and that that was enough.

For all of his extraordinariness, Louis was also an almost unbelievably regular guy. The title heavyweight champion of the world may suggest its holder is the planet’s most powerful man, but outside the ring that certainly was not the case with Louis. Clean-living during his fighting days, Louis later developed a fondness for Sonny Liston, another fighter more expressive with his fists than with words, largely because of their shared appetites and weaknesses (for gambling, for drugs, for women). When he did make political statements, Louis opted for bland rather than radical. He endorsed Republican Wendell Willkie rather than Franklin D. Roosevelt in the 1940 presidential election. In one of his most quoted comments - one used alongside his image on World War II-era military recruitment posters - he proclaimed America to be “on God’s side.” Though younger journalists eventually came to treat the broke ex-boxer as a pathetic figure, and his gig at Caesars undignified, Louis sincerely enjoyed his job in the casino. He never thought it ignominious to have people want to shake his hand, ask for his autograph and request that he stand next to them at the gaming tables for luck. He contentedly filled the time before reporting to work with hours on the golf course or at home watching television.

Solving the mystery of Joe Louis would mean explaining where this humble, sometimes passive-seeming man got the will it takes to become heavyweight champion of the world and keep the title for as long as he did. “It’s no easy job getting up in that ring,” he said; “you got to have a special kind of balls.” Yet from the way others describe him, and the way he described himself, he never was the intensely ambitious type. “You know something, I never was a leader,” he admits in his 1978 autobiography. “I always followed other people.” His does not come across as the personality of a determined competitor but, at least when wearing boxing gloves, that is what he was. In Joe Louis: My Life, he names some of the people he followed, like Roxborough, Black and Blackburn (whom he always called “Chappie”). In the process he hints at the attitudes that led to his accomplishments. “Hard work never bothered me,” he says of his teenager’s job delivering block of ice, “and it built me up for my profession.” At Brewster’s East Side Gymnasium in Detroit, he discovered that he had both a knock-out punch and a lot to learn. “A ‘natural’ dancer has to practice hard. A ‘natural’ painter has to paint all the time, even a ‘natural’ fool has to work at it,” he realizes. “I had the God-given equipment to be a professional fighter, but I had to train at it, and train damn hard.” Even so, the unstoppable drive never gets articulated, though he did express it wordlessly.

One particular paragraph in Joe Louis: My Life highlights the jarring contrast between being the man who “can lick any son-of-a-bitch alive,” as Sullivan defined the heavyweight champion, and Louis’s own lack of self-reliance.

Besides my momma, Mr. Roxborough, Mr. Black, and Chappie Blackburn were my teachers. Seems like simple things they taught me, now, but then there were a lot of things I never had known - proper methods for washing my ears, combing my hair, and general grooming; how to hold a fork. Chappie took care of teaching me the fighting end.

Louis here recalls the time when he was already a twenty years old professional in 1934 - just three years before seizing the title Sullivan once held. He had the confidence, the inner resources, to succeed, but presents himself as indifferent to business matters. “When my managers asked me how I felt about it,” he recalls of matching him against ex-champ Primo Carnera, “I told them they were the managers and what they said was fine with me.” Publicly, at least, he only wanted to assert himself in the ring.

In his bid to elucidate the meaning of Louis’s life, Roberts visits the storehouse of worn out lingo too many times. “No one plays boxing. Fighting is not a game,” he says, as have many others before him and many more will no doubt continue to say. He is not alone in writing as if there were a requirement to call New York City generally and Madison Square Garden specifically the Mecca of boxing. Nonetheless, he frequently displays keen judgment, as when he dispatches Louis’s sturdy but unremarkable immediate predecessor in a couple of sentences. (“Braddock was no Dempsey. He was no Tunney. He was not even a Max Baer.”) The former dock worker and welfare recipient who unexpectedly became champion in 1935 may have excited Americans during the Depression’s darkness, but he was neither the athlete nor the larger-than-life figure that Louis was. Braddock fought no one between claiming the title and losing it to Louis two years later. Louis, in contrast, was - to risk cliched usage - a fighting champion. He defended his title just two months after winning it and faced challengers several times a year until the war put such contests on hold. He fought seven title fights (and two exhibitions) in 1941 alone. Braddock may have been an upstanding fellow with a good story. (His repaying the money his family received as government aid contributed to the Cinderella Man’s public image, but Louis did exactly the same thing once he started earning money and his family in Detroit no longer needed public assistance.) Yet he never looked like a hero with real staying power the way Louis did.

Despite the unedifying aspects of its later chapters, the Joe Louis saga is the story of pride, innate and contagious pride. “They were real proud,” Ruth Owens told McRae regarding her husband and his friend Joe. “They might seem quiet if you put ’em next to any of these modern fellers you got today - but quietness don’t diminish pride.” It may diminish heroes’ legends in an age that has no use for quietness, however. (For years before his death in 2009, Budd Schulberg was rumored to be collaborating with Spike Lee on a movie title Save Me, Joe Louis. It would be fascinating to see how the writer of On the Waterfront and the director of Do the Right Thing and Malcolm X aimed to introduce Louis to a new audience unaccustomed his style of pride.)

Louis was indisputably a superior boxer - one of the best ever - and he had a huge impact on his historical period though the fights with Schmeling, his dignity as a public figure, his efforts in the military and in many other ways. In the end, however, even the greatest of heroes rusted as “a relic of another time and another America,” Roberts writes. Louis may have been a potent symbol for his era, but with each passing year, as memory of him and what he once meant fades, his claims to the designation hero for all ages becomes less and less secure. If Louis was champion “in an era when heavyweight champion of the world was, in the view of many, the greatest man in the world,” as journalist Red Smith put it, then where does that leave him when boxing matters to relatively few people? If heroes are supposed to take firm public stands on issues of the day, then who will cheer a reticent man who preferred to keep quiet around reporters?" With his Joe Louis, Roberts implies the answers to those questions are “nowhere” and “no one.” He offers a reminder of why Louis mattered and a resigned realization that the man just might not matter to many people any more. “If he was not a champ for all seasons,” Schulberg writes of Jack Dempsey, “he was certainly the right man for the right time.” Similarly, according to Roberts, Louis, as both a man and a symbol, “gave hope to Americans during a troubled time.” Louis may have been “the greatest heavyweight fighter who every lived,” as Schulberg says (and innumerable others have said), but he too may have been a hero for his times. If Louis cannot hold onto the title, then maybe there simply is no such thing as a hero for all seasons.

Perhaps it’s appropriate, then, that those monuments to Louis stand where they do. My hometown once epitomized industrial strength, but like Louis no longer looks so mighty. Heroes without a Country inadvertently indicates the status of Louis’s legacy. In it, McRae doubly misstates the location of the twenty-four-foot Robert Graham sculpture of Louis’s forearm and fist, which he says was erected at Jefferson and “Windsor” and was later relocated to the Detroit Institute of Arts. In fact, it remains at Jefferson and Woodward, even if McRae doesn’t know it - and even if too few appreciate why it was put there in the first place.

Despite the evidence, a part of me wants to sing “King Joe (Joe Louis Blues),” where Richard Wright says: “He ain’t gone and he’s still the king.”

January 2011

From guest contributor John G. Rodwan, Jr.

|