Motorsports draw the interest of millions of fans each year. In 2011, according to Street and Smith’s Sorts Business Daily, auto racing was the fourth most popular sport in the United States, behind pro football, baseball, and college football, but ahead of pro basketball, college basketball, hockey, etc. One of the signature events on the racing calendar is the Indianapolis 500, held over Memorial Day weekend each year. Dating from 1911, the “500” attracts hundreds of thousands of fans to the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. Millions of viewers watch the race on television and/or listen in on the Speedway’s radio network. For decades, the facility only offered one event per year, the “500.” Indeed, for some fans the fact that the facility only presented one event per year added to the allure of the month of May.

Tony George, the CEO of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway from 1989 to 2009, was one of the most important figures in automobile racing in the United States. Under his leadership, the Indianapolis Motor Speedway expanded its events to include the Brickyard 400 of NASCAR (since 1994), the International Race of Champions (1998), the United States Grand Prix of Formula One (2000-2007), and the Red Bull Indianapolis Grand Prix of MotoGP (since 2008). George may be best known, however, for creating the Indy Racing League (IRL) and the IRL-CART split of 1996, which marked the end of an era in open-wheeled racing in the United States. The reverberations of the “split” are still felt today.

Tony George is the grandson of Anton “Tony” Hulman, who owned the Indianapolis Motor Speedway from 1946 until his death in 1977. In 1955, when the AAA discontinued their practice of sanctioning motor racing, Hulman was instrumental in the creation of the United States Auto Club (USAC), which became the primary sanctioning body for open-wheeled racing in the United States. However, in 1979, after Hulman had passed away, the owners of several racing teams, including Dan Gurney, U.E. “Pat” Patrick, and Roger Penske, formed CART – Championship Automobile Racing Teams. When George took over as CEO of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway in 1989, CART was the sanctioning body for all “Indy car” races except the Indianapolis 500. USAC remained the sanctioning body of the Indianapolis 500 until 1995. These developments are described in detail in The 1996 Indianapolis 500 Yearbook (1996), edited by Carl Hungness; the United States Auto Club: 50 Years of Speed and Glory (2006), by Dick Wallen; and the Autocourse Official History of the Indianapolis 500 (2006), by Donald Davidson and Rick Shaffer.

It was in the early 1990s that Tony George became concerned that promoters and track owners had too little say in CART’s direction. From his perspective, the CART directors were too interested in street circuits, employed too many international drivers, and were not vigilant enough in holding down costs – all to the detriment of the sport and the most traditional oval of them all, the Indianapolis 500. Conflict was not necessarily new or unique to US open-wheeled auto racing. A 1962 article in Popular Mechanics, titled, “Is the Indy Race in a Rut?” noted complaints that the cars of that day were too similar. There is also tension between track owners, promoters, and sanctioning bodies in Formula One, as noted in Sport Worlds: A Sociological Perspective (2002) by Joseph Maguire, Grant Jarvie, Louise Mansfield, and Joseph Bradley. Brian Donovan’s insightful biography, Hard Driving: The Wendell Scott Story The American Odyssey of NASCAR’s First Black Driver (2008), offers numerous examples of the tensions that exist in automobile racing.

Tony George’s concerns were warranted. In 1993, fifteen of thirty-three drivers in the “500” were “foreign” born. At the time, Jeff Gordon was a rising star in the lower-levels of open wheel racing, winning the United States Auto Club (USAC) midget title in 1990 and the USAC Silver Crown title in 1991. But Gordon could not find a ride at the next level. Instead of moving up to race at Indianapolis, he jumped to NASCAR, and became a four-time champion and major fan attraction. There were other issues. In May 1994, it was revealed that Roger Penske, owner of the most successful CART team, had worked with Mercedes-Benz to develop a special engine for the Indianapolis 500. Penske drivers Al Unser Jr. and Emerson Fittipaldi started first and third and dominated the event, with Fittipaldi leading 145 (of 200) laps. The major excitement of the day occurred on lap 185 when Fittipaldi, trying to put second place Unser Jr. a lap down, went too low on the race track, lost control, and crashed. Unser inherited the lead and the victory. Together, they led 193 of 200 relatively uncompetitive laps. In an ironic twist, and in part because they had over-relied on the Mercedes-Benz engine the year before, the storied Penske team was uncompetitive and failed to qualify for the 1995 “500.” In this strange turn of events, the 1995 race was deprived of two major stars, defending champion Unser Jr. and two-time “500” champion and former F1 champion Fittipaldi. All of this is chronicled in Donald Davidson and Rick Shaffer’s official history of the Indianapolis 500.

It was in this context that in May 1995 Tony George announced he was forming the Indy Racing League (IRL), which would sanction not only the Indianapolis 500 but also other events that would compete with CART. Most of the top teams and drivers, including Penske Racing, with Unser Jr. and Fittipaldi, Newman/Haas Racing, with Michael Andretti, and Team Rahal, with owner/driver Bobby Rahal, remained with CART. A.J. Foyt, Jr.’s team went with the IRL, as did John Menard, with Tony Stewart as a driver. What started as an uneasy state of tolerance transitioned to open warfare when it was announced that 25 of the 33 starting positions for the 1996 “500” would be reserved for IRL teams. CART countered by scheduling the “U.S. 500” on the same day as the Indianapolis 500, May 26, 1996. The U.S. 500 was held at Michigan International Speedway, owned at the time by Roger Penske. In many ways, the first lap of the U.S. 500 summarizes the next decade for open-wheeled racing in the United States. As the race was about to start, a major accident took out a large portion of the field. It was easier for the CART teams to regroup and re-start the race than it was for open-wheel racing to avoid the damage of the CART-IRL split.

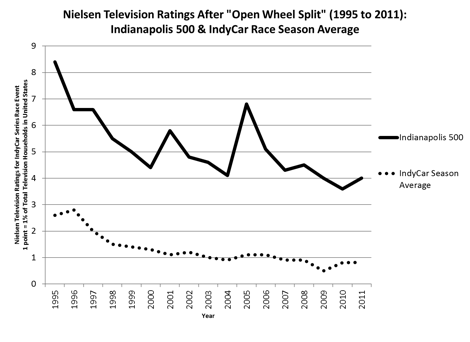

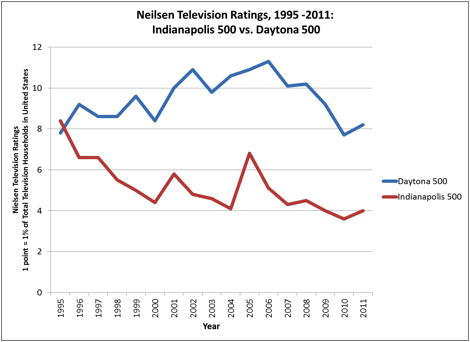

Street & Smith’s SportsBusiness Daily publishes data on sporting events provided by Neilsen Media Research. As shown in Figure 1, television ratings for the Indianapolis 500 declined sharply between 1995 and 2000. The ratings for open-wheel racing in general suffered the same fate. In contrast, as shown in Figure 2, ratings for NASCAR’s flagship event, the Daytona 500, soared. The return of top teams to Indianapolis, like Ganassi Racing (in 2000), and Penske Racing (in 2001) did not mitigate the damage. By 2008, when the IndyCar Series (renamed from the IRL in 2003) and the Champ Car World Series (CART’s successor) were unified, it was too late. The economic downtown that hit the world economy in that year hurt the IndyCar Series and NASCAR, exacerbating an already tough situation for open-wheeled racing.

Figure 1

Figure 2

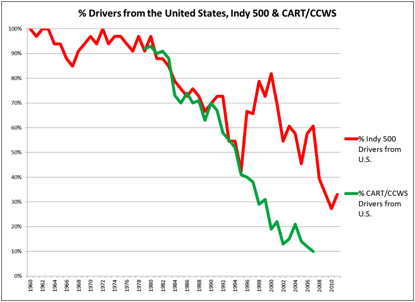

In creating the IRL, Tony George wanted to: 1) support oval racing by minimizing the number of street circuits in US open-wheeled racing; 2) increase the number of US born drivers; and 3) limit skyrocketing costs. With the benefit of hindsight, it is tempting to argue that the IRL was a failure. Street and road courses remain prominent on the IRL/IndyCar schedule. For 2011, Chicagoland’s oval – the site of some of the best racing in recent years – was off the circuit. Only seven of the seventeen races of 2005 remain on the schedule. Eight of the ten races dropped were on oval speedways, and only five of seventeen races in 2012 will be on ovals. As shown in Figure 3, with the IRL there was a short-term increase in US born drivers in the Indianapolis 500. But that declined over time and international drivers like Helio Castroneves (Brazil), Tony Kanaan (Brazil), Scott Dixon (New Zealand), and Dario Franchitti (Scotland) have dominated Indy cars in recent years. And while Sarah Fisher has shown that talent and hard work will pay off for IRL/IndyCar Series participants, the series has suffered because stars like Tony Stewart, Sam Hornish, and Ryan Newman have joined Jeff Gordon in NASCAR. Danica Patrick’s recent decision to move to NASCAR does not bode well. And costs continue to climb.

Figure 3

Percentage of Drivers from the United States, Indianapolis 500 and CART,

1960-2012

(Indianapolis 500 in red; CART/Champ Car World Series in green)

Source: Indianapolis 500 Annual Programs

But there is another aspect of the IRL/IndyCar era that cannot be underestimated. Under CART, some car owners had complained that they did not have equal access to top equipment, that money and power had too much influence on racing. These issues are not confined to open-wheeled racing in the United States. The interested reader may refer to Jay Coakley’s Sports in Society: Issues and Controversies (2004) and the previously noted biography of NASCAR’s Wendell Scott. The IRL’s response was important. The IRL mandated chassis and engine combinations that were made available to all participants. In 1997, as noted by Al Stilley in an article titled “The New Engines” that appeared in the Indianapolis 500 Yearbook for that year (edited by Carl Hungness), for the first time in “modern history” all thirty-three cars in the Indianapolis 500 had normally aspirated production-based engines. The price tag was “only” $75,000 per engine. By 2006, the Honda engine and Dallara chassis combination were a common package for small and large budget competitors. Honda was the exclusive provider of engines between 2006 and 2011; in 2012, Chevrolet and Lotus joined Honda as engine manufacturers for the series. It appears that the IRL mandates helped smaller teams, like the one organized by driver/owner Sarah Fisher in 2008 (pictured above at Indianapolis with co-owner and father-in-law John O'Gara in 2009) (Photo: Robert White). The mandates were also good for competition. In 2011, the late Dan Wheldon, in a “one-race” deal for the small team of Bryan Herta Motorsports, won the “500.” That same year, Ed Carpenter (Tony George’s stepson), driving for Sarah Fisher Racing (now Sarah Fisher Hartman Racing), won the Kentucky Indy 300 (narrowly beating Dario Franchitti).

This more level playing field may continue into the future. In 2013, as part of a new design specification, teams will be limited to two “aero kits” per season. This change should make it easier for small budget teams to compete, as large budget teams will be unable to outspend the competition and employ multiple packages tailored to specific race tracks. This factor is described in Geoffrey Miller’s online article, “IndyCar chooses Dallara Chassis ‘Aero Kits’ for New Car Design” (see http://motorsports.fanhouse.com/2010/07/14/indycar-chooses-dallara-chassis-aero-kits-for-new-car-design/).

Racing attracts millions of fans for a variety of reasons. Some fans are attracted by the danger inherent in driving an open-wheeled race car flat out at 220 plus miles per hour, inches from other cars and unforgiving walls. Other fans are attracted by the technology that allows for 220 plus miles per hour racing. And for some racing fans, whether it is IndyCar, NASCAR, F1, Moto GP, or H1 Unlimited hydroplanes, the thrill is in watching close, high-speed, competition. In the following, we compare the level of competition at the Indianapolis 500 for the “CART era” (1979-1995) and the “IRL/IndyCar era” (1996-2011).

Measures of Competition

We focus on competition at the Indianapolis 500 because it was one of very few constants in open-wheeled racing between 1979 and 2011. The first Indianapolis 500 was held in 1911 and except for the war years of 1917-18 and 1942-45, the race has been held each year at the end of May, around Memorial Day. Over the years, the track has changed from its original brick surface, but on a year-to-year basis the track itself has in essence been the same relatively flat four-cornered oval. In contrast, other races, on both the CART and IRL schedules, have been subject to change. For example, in various years, the Chicagoland IRL race was held in August or September. The Homestead IRL/IndyCar races (2001-2010) moved from April to March to February and then to October. Also, the Indianapolis race is the marquee event for open-wheeled racing with national coverage and interest. A 2004 report by the Center for Urban Policy and the Environment at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, “Motorsports Industry in the Indianapolis Region,” describes the tremendous influence of the “500” on Indiana’s economy, and beyond. Indeed, the fate of Indianapolis race is important for automobile racing in general, as described by Philip O’Kane, in his article “A History of the ‘Triple Crown’ of Motor Racing: The Indianapolis 500, the Le Mans 24 Hours, and the Monaco Grand Prix,” that appeared in the International Journal of the History of Sport (2011).

In the following, we consider four different measures of the level of competition in the Indianapolis “500” between 1979 and 2011. The first and probably most important indicator of the level of competition at Indianapolis is the winner’s margin of victory. The “500” in both sets of years saw some incredibly close finishes; the five closest finishes in the history of the race occurred between 1979 and 2011. These include the 1982 race in which Gordon Johncock held off a hard-charging Rick Mears by 16/100ths of a second, and the 2006 race when Sam Hornish passed rookie Marco Andretti on the front stretch of the final lap, winning by an even closer 6/100ths of a second – a few feet. But these races may be exceptions. After excluding those races that ended under a yellow, we look at the average margin of victory between 1979 and 1995 (the “CART era”) and 1996 and 2011 (the “IRL/IndyCar Series era”). Our data are from the “Official Box Score” for each “500,” which is readily available in various sources, including Donald Davidson and Rick Shaffer’s “Official” history 1979-2006, recent Indianapolis 500 annual programs, and various web sites (e.g., the Indianapolis Motor Speedway web pages). The “500” ran the full 200 laps of every race in the CART years, although two races (1988 and 1989) ended under a yellow flag because of crashes. In the IRL/IndyCar era, the 2004 (180 laps) and 2007 (166 laps) races were shortened by rain, and the 2002, 2005, 2010 and 2011 races ended under a yellow flag because of a crash.

A second measure of competition between 1979 and 2011 assesses how frequently the lead changed. Presumably, more competitive races have more drivers challenging for the lead. Because not every race completed the distance, we examine the “Lead Change Ratio” (the total number of laps divided by the total number of lead changes); that is, the ratio of lead changes per total number of laps. A third, and similar, indicator of competitiveness is the percentage of laps led by the driver who led the most laps in a given race. This analysis captures the perspective that the more one driver dominates a race, the less competitive that race is. The final measure of competition considers the number of cars completing the race. The more cars in the hunt, the more competitive the race (see Table 1).

Table 1

Indianapolis 500 Results, 1979-1995 (CART years)

and 1996-2011 (IRL-IndyCar Series) |

Year |

Margin of Victory (seconds) |

Number

Of Lead

Changes |

Lead Change Ratio |

Percentage Laps

Led by

Lap Leader |

Laps Completed |

Cars Finishing/On

Lead Lap at End |

CART |

|

|

|

|

|

|

1979 |

45.69 |

8 |

25.00 |

.45 (89) |

200 |

3 |

1980 |

29.92 |

21 |

9.52 |

.59 (118) |

200 |

4 |

1981 |

5.18 |

24 |

8.33 |

.45 (89) |

200 |

2 |

1982 |

.16 |

16 |

12.50 |

.39 (77) |

200 |

2 |

1983 |

11.17 |

16 |

12.50 |

.49 (98) |

200 |

3 |

1984 |

100 |

16 |

12.50 |

.60 (119) |

200 |

1 |

1985 |

2.47 |

12 |

16.67 |

.54 (107) |

200 |

3 |

1986 |

1.44 |

19 |

10.53 |

.38 (76) |

200 |

4 |

1987 |

4.49 |

10 |

20.00 |

.85 (170) |

200 |

2 |

1988 |

Yellow-crash |

9 |

22.22 |

.46 (91) |

200 |

2 |

1989 |

Yellow-crash |

15 |

13.33 |

.79 (158) |

200 |

1 |

1990 |

10.87 |

6 |

33.33 |

.64 (128) |

200 |

3 |

1991 |

3.14 |

18 |

11.11 |

.49 (97) |

200 |

2 |

1992 |

.04 |

18 |

11.11 |

.80 (160) |

200 |

4 |

1993 |

2.86 |

23 |

8.70 |

.36 (72) |

200 |

10 |

1994 |

8.6 |

10 |

20.00 |

.73 (145) |

200 |

2 |

1995 |

2.48 |

23 |

8.70 |

.30 (59) |

200 |

7 |

CART Average |

15.23 |

|

12.88 |

.54 (1,853) |

3,400 |

3.23 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

IRL/IndyCar |

|

|

|

|

|

|

1996 |

.69 |

15 |

13.33 |

.24 (47) |

200 |

3 |

1997 |

.57 |

16 |

12.50 |

.32 (64) |

200 |

5 |

1998 |

3.19 |

23 |

8.70 |

.38 (76) |

200 |

3 |

1999 |

6.56 |

17 |

11.76 |

.33 (66) |

200 |

4 |

2000 |

7.18 |

6 |

33.33 |

.84 (167) |

200 |

6 |

2001 |

1.73 |

13 |

15.38 |

.26 (52) |

200 |

6 |

2002 |

Yellow-crash |

19 |

10.53 |

.43 (85) |

200 |

11 |

2003 |

.30 |

14 |

14.29 |

.32 (63) |

200 |

10 |

2004 |

Yellow-rain |

17 |

10.59 |

.51 (91) |

180 |

14 |

2005 |

Yellow-crash |

27 |

7.41 |

.39 (77) |

200 |

9 |

2006 |

.06 |

14 |

14.29 |

.74 (148) |

200 |

10 |

2007 |

Yellow-rain |

23 |

7.22 |

.50 (83) |

166 |

13 |

2008 |

1.74 |

18 |

11.11 |

.58 (115) |

200 |

15 |

2009 |

1.98 |

6 |

33.33 |

.33 (66) |

200 |

19 |

2010 |

Yellow-crash |

13 |

15.38 |

.78 (154) |

200 |

14 |

2011 |

Yellow-crash |

23 |

8.70 |

.36 (73) |

200 |

12 |

IRL /Indycar Average |

2.40 |

|

11.92 |

.45 (1,427) |

3,146 |

9.07

(for complete races) |

1979-2011 |

Average |

10.10 |

|

12.39 |

.50 (3,280) |

6,546 |

5.9 |

As shown in Table 1, between 1979 and 2011, the average margin of victory in the Indianapolis 500 for races that went the distance was 10.1 seconds. Comparing the CART (1979-1995) years with the IRL/IndyCar years (1996-2011) shows that IRL races had closer finishes. Under CART, the average margin of victory was 15.23 seconds. In the IRL and IndyCar years, the average margin of victory was a much closer 2.40 seconds. Some of this result is skewed by the dominating performance of Rick Mears in 1984. Mears was two full laps ahead of second place Roberto Guerrero when he received the checkered flag, and he was the only driver to complete the distance. Under the assumption that Mears was lapping at 180 mph (fifty seconds per lap), we have assigned a margin of victory of 100 seconds (the average speed for the race was 163.212 mph; Mears started third, with an average qualifying speed of 207.847 mph). However, even if the 1984 race is excluded from the calculation, the average margin of victory in the CART years remains significantly higher, at 9.17 seconds. The Johncock-Mears finish in 1982 (CART) was phenomenal, but under the IRL the Indianapolis 500s of 1996, 1997, 2003, and 2006 were all decided by a margin of less than one second. For fans interested in close finishes, the IRL and its successor, the IndyCar Series, have delivered.

Similar results are found for the other three indicators of competition. The weakest evidence of increased competition is found with the lead change measure. In the CART era, the lead in the Indianapolis 500 changed 264 times over 3,400 laps, or not quite every thirteen laps (3,400/264=12.88). Under the IRL/IndyCar, there were 264 lead changes over 3,146 laps, a little more than once every twelve laps (3,146/264=11.92). CART races were more likely to be dominated by one driver. Between 1979 and 1995, the car that led the most laps in each race led 1,853 of 3,400 total laps. That is, on average, one car led 54% of the lead laps. Under the IRL, the car that led the most laps led, on average, 45% of all laps (1,427 of 3,146 laps). Finally, as indicated by the number of cars completing the race, the data again show that the Indianapolis 500 became more competitive under the IRL. Between 1979 and 1995, the leader completed the full 200 laps in each race. In these years, an average of three cars were on the lead lap when the race was stopped (55 cars/17 races = 3.23 cars). In contrast, between 1996 and 2011, fourteen races went the full distance. In these races, an average of nine cars were on the lead lap when the race was stopped (127 laps led/14 races = 9.07). Further, in IRL/IndyCar races, there was probably more competition for positions one through ten, which may also help explain four races (2002, 2005, 2010 and 2011) ending under a yellow flag even though they went the distance. This factor was especially evident in 2011 when race leader and rookie J.R. Hildebrand of Panther Racing crashed on the final lap and was passed on the front stretch by the late Dan Wheldon.

Conclusion

Since World War II, championship level open-wheeled automobile racing in the United States has seen a succession of sanctioning bodies, including the American Automobile Association, the United States Auto Club, Championship Auto Racing Teams, and the Indy Racing League. For various reasons, each sanctioning body pursued different rules for participation, and arguably each sanctioning body represents a different era in the modern history of open-wheeled racing. In 1995, Tony George, CEO of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway from 1989 until 2009, created the Indy Racing League in order to support oval racing, foster the development of US-born race car drivers, and limit costs. Because we do not know what would have happened if George had not created the IRL, it is impossible to determine if, for example, there are more US-born drivers pursuing open-wheeled careers than there would have been without the IRL. Data do show, however, that the IRL-CART split did hurt fan interest.

Data also show that for fans interested in close, high-speed competition, the Indy Racing League/IndyCar Series has been a success. The flagship race of open wheeled racing in the United States, the Indianapolis 500, became significantly more competitive under the IRL than it was in the CART era. We recognize that for some fans a great race is one in which a team, or driver, dominates. Certainly in 1984 and 1994, Team Penske demonstrated excellence and set a standard that is to be applauded. The same may be said for the performance of Dario Franchitti and Ganassi Racing in 2010. That said, on average the IRL led to closer finishes, more lead changes, less domination by one driver/car, and more cars completing the distance. One aspect of more competition that remains to be further examined, however, is the degree to which more competitive racing is also more dangerous racing. The number of recent Indianapolis 500s finishing under a yellow light may be an indicator of more dangerous racing. Another such indicator may be the fifteen car accident at the final race of the 2011 IndyCar season, at Las Vegas, that claimed the life of Dan Wheldon.

In the long run, increased competition may produce a better product for fans. Interested readers may refer to various sources that address this issue, including Jeffery Borland and Robert MacDonald’s article, “Demand for Sport,” in the Oxford Review of Economic Policy (2003), Stephen Ross and Stefan Szymanski’s article “Open Competition in League Sports,” in the Wisconsin Law Review (2002), and the Handbook on the Economics of Sport (2006), edited by Wladimir Andreff and Stefan Syzmanski. Whatever the future, claims that the IRL-CART split was a disaster for open wheeled racing should be qualified. The split cost the sport some fans and sponsors, but it also produced more competitive racing. More competitive racing may bring back those fans and sponsors.

May 2013

From guest contributors Robert W. White and Andrew J. Baker, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis |